The Brisbane Line 1909 - 1963

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cabinet Government: Australian Style1

7. Cabinet government: Australian style1 Patrick Weller AO So Tony Blair has gone. It is said of Tony Blair that he killed the cabinet in Britain, that he held a few meetings that didn't last very long and that in any one year there were about half a dozen decisions made by cabinetÐin a year, not in a meeting. Gordon Brown will come into office and change the way the decisions get made in Britain. Not because he needs to, but because he has to, in order to illustrate that he is a different sort of leader. So the shape of cabinet will change, even if the outcomes might not, or at least it will change initially, because leaders can shape cabinets to their own style and their own preoccupations. Brown will be different. His former head of department called him a Stalinist, or said that he was Stalinist in the way that he approached decision making, allowing no opposition, no debate. It will be interesting to see if he tries to run the English government as Prime Minister the same way as he acted when he was Chancellor. But if the British system of organising and running cabinet is compared with the Australian style, it's really quite different. Cabinet here still appears to exist. The ministers meet regularly, they have a formal agenda, a working committee system and a process by which the majority of issues are at least discussed in cabinet, even if some of the decisions might have been preordained and decided beforehand. I want to talk about the contrasts between the British and the Australian system. -

Major General James Harold CANNAN CB, CMG, DSO, VD

Major General James Harold CANNAN CB, CMG, DSO, VD [1882 – 1976] Major General Cannan is distinguished by his service in the Militia, as a senior officer in World War 1 and as the Australian Army’s Quartermaster General in World War 2. Major General James Harold Cannan, CB, CMG, DSO, VD (29 August 1882 – 23 May 1976) was a Queenslander by birth and a long-term member of the United Service Club. He rose to brigadier general in the Great War and served as the Australian Army’s Quartermaster General during the Second World War after which it was said that his contribution to the defence of Australia was immense; his responsibility for supply, transport and works, a giant-sized burden; his acknowledgement—nil. We thank the History Interest Group and other volunteers who have researched and prepared these Notes. The series will be progressively expanded and developed. They are intended as casual reading for the benefit of Members, who are encouraged to advise of any inaccuracies in the material. Please do not reproduce them or distribute them outside of the Club membership. File: HIG/Biographies/Cannan Page 1 Cannan was appointed Commanding Officer of the 15th Battalion in 1914 and landed with it at ANZAC Cove on the evening of 25 April 1915. The 15th Infantry Battalion later defended Quinn's Post, one of the most exposed parts of the Anzac perimeter, with Cannan as post commander. On the Western Front, Cannan was CO of 15th Battalion at the Battle of Pozières and Battle of Mouquet Farm. He later commanded 11th Brigade at the Battle of Messines and the Battle of Broodseinde in 1917, and the Battle of Hamel and during the Hundred Days Offensive in 1918. -

A 'Common-Sense Revolution'? the Transformation of the Melbourne City

A ‘COMMON-SENSE REVOLUTION’? THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE MELBOURNE CITY COUNCIL, 1992−9 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy April, 2015 Angela G. Munro Faculty of Business, Government and Law Institute for Governance and Policy Analysis University of Canberra ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis is the culmination of almost fifty years’ interest professionally and as a citizen in local government. Like many Australians, I suspect, I had barely noticed it until I lived in England where I realised what unique attributes it offered, despite the different constitutional arrangements of which it was part. The research question of how the disempowerment and de-democratisation of the Melbourne City Council from 1992−9 was possible was a question with which I had wrestled, in practice, as a citizen during those years. My academic interest was piqued by the Mayor of Stockholm to whom I spoke on November 18, 1993, the day on which the Melbourne City Council was sacked. ‘That couldn’t happen here’, he said. I have found the project a herculean labour, since I recognised the need to go back to 1842 to track the institutional genealogy of the City Council’s development in the pre- history period to 1992 rather than a forensic examination of the seven year study period. I have been exceptionally fortunate to have been supervised by John Halligan, Professor of Public Administration at University of Canberra. An international authority in the field, Professor Halligan has published extensively on Australian systems of government including the capital cities and the Melbourne City Council in particular. -

Strategy-To-Win-An-Election-Lessons

WINNING ELECTIONS: LESSONS FROM THE AUSTRALIAN LABOR PARTY 1983-1996 i The Institute of International Studies (IIS), Department of International Relations, Universitas Gadjah Mada, is a research institution focused on the study on phenomenon in international relations, whether on theoretical or practical level. The study is based on the researches oriented to problem solving, with innovative and collaborative organization, by involving researcher resources with reliable capacity and tight society social network. As its commitments toward just, peace and civility values through actions, reflections and emancipations. In order to design a more specific and on target activity, The Institute developed four core research clusters on Globalization and Cities Development, Peace Building and Radical Violence, Humanitarian Action and Diplomacy and Foreign Policy. This institute also encourages a holistic study which is based on contempo- rary internationalSTRATEGY relations study scope TO and WIN approach. AN ELECTION: ii WINNING ELECTIONS: LESSONS FROM THE AUSTRALIAN LABOR PARTY 1983-1996 By Dafri Agussalim INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS UNIVERSITAS GADJAH MADA iii WINNING ELECTIONS: LESSONS FROM THE AUSTRALIAN LABOR PARTY 1983-1996 Penulis: Dafri Agussalim Copyright© 2011, Dafri Agussalim Cover diolah dari: www.biogenidec.com dan http:www.foto.detik.com Diterbitkan oleh Institute of International Studies Jurusan Ilmu Hubungan Internasional, Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik Universitas Gadjah Mada Cetakan I: 2011 x + 244 hlm; 14 cm x 21 cm ISBN: 978-602-99702-7-2 Fisipol UGM Gedung Bulaksumur Sayap Utara Lt. 1 Jl. Sosio-Justisia, Bulaksumur, Yogyakarta 55281 Telp: 0274 563362 ext 115 Fax.0274 563362 ext.116 Website: http://www.iis-ugm.org E-mail: [email protected] iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This book is a revised version of my Master of Arts (MA) thesis, which was written between 1994-1995 in the Australian National University, Canberra Australia. -

“Come on Lads”

“COME ON LADS” ON “COME “COME ON LADS” Old Wesley Collegians and the Gallipoli Campaign Philip J Powell Philip J Powell FOREWORD Congratulations, Philip Powell, for producing this short history. It brings to life the experiences of many Old Boys who died at Gallipoli and some who survived, only to be fatally wounded in the trenches or no-man’s land of the western front. Wesley annually honoured these names, even after the Second World War was over. The silence in Adamson Hall as name after name was read aloud, almost like a slow drum beat, is still in the mind, some seventy or more years later. The messages written by these young men, or about them, are evocative. Even the more humdrum and everyday letters capture, above the noise and tension, the courage. It is as if the soldiers, though dead, are alive. Geoffrey Blainey AC (OW1947) Front cover image: Anzac Cove - 1915 Australian War Memorial P10505.001 First published March 2015. This electronic edition updated February 2017. Copyright by Philip J Powell and Wesley College © ISBN: 978-0-646-93777-9 CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................. 2 Map of Gallipoli battlefields ........................................................ 4 The Real Anzacs .......................................................................... 5 Chapter 1. The Landing ............................................................... 6 Chapter 2. Helles and the Second Battle of Krithia ..................... 14 Chapter 3. Stalemate #1 .............................................................. -

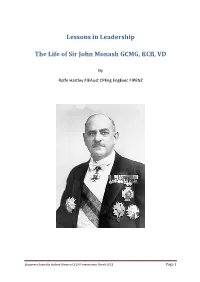

Lessons in Leadership the Life of Sir John Monash GCMG, KCB, VD

Lessons in Leadership The Life of Sir John Monash GCMG, KCB, VD By Rolfe Hartley FIEAust CPEng EngExec FIPENZ Engineers Australia Sydney Division CELM Presentation March 2013 Page 1 Introduction The man that I would like to talk about today was often referred to in his lifetime as ‘the greatest living Australian’. But today he is known to many Australians only as the man on the back of the $100 note. I am going to stick my neck out here and say that John Monash was arguably the greatest ever Australian. Engineer, lawyer, soldier and even pianist of concert standard, Monash was a true leader. As an engineer, he revolutionised construction in Australia by the introduction of reinforced concrete technology. He also revolutionised the generation of electricity. As a soldier, he is considered by many to have been the greatest commander of WWI, whose innovative tactics and careful planning shortened the war and saved thousands of lives. Monash was a complex man; a man from humble beginnings who overcame prejudice and opposition to achieve great things. In many ways, he was an outsider. He had failures, both in battle and in engineering, and he had weaknesses as a human being which almost put paid to his career. I believe that we can learn much about leadership by looking at John Monash and considering both the strengths and weaknesses that contributed to his greatness. Early Days John Monash was born in West Melbourne in 1865, the eldest of three children and only son of Louis and Bertha. His parents were Jews from Krotoshin in Prussia, an area that is in modern day Poland. -

03 Chapters 4-7 Burns

76 CHAPTER 4 THE REALITY BEHIND THE BRISBANE LINE ALLEGATIONS Curtin lacked expertise in defence matters. He did not understand the duties or responsibilities of military commanders and never attended Chiefs of Staff meetings, choosing to rely chiefly on the Governments public service advisers. Thus Shedden established himself as Curtins chief defence adviser. Under Curtin his influence was far greater than 1 it had ever been in Menzies day. Curtins lack of understanding of the role of military commanders, shared by Forde, created misunderstandings and brought about refusal to give political direction. These factors contributed to events that underlay the Brisbane Line controversy. Necessarily, Curtin had as his main purpose the fighting and the winning of the war. Some Labor politicians however saw no reason why the conduct of the war should prevent Labor introducing social reforms. Many, because of their anti-conscriptionist beliefs, were unsympathetic 2 to military needs. Conversely, the Army Staff Corps were mistrustful of their new masters. The most influential of their critics was Eddie Ward, the new Minister for Labour and National Service. His hatred of Menzies, distrust of the conservative parties, and suspicion of the military impelled him towards endangering national security during the course of the Brisbane Line controversy. But this lay in the future in the early days of the Curtin Government. Not a great deal changed immediately under Curtin. A report to Forde by Mackay on 27 October indicated that appreciations and planning for local defence in Queensland and New South Wales were based on the assumption that the vital area of Newcastle-Sydney-Port Kembla had priority in defence. -

04 Chapters 8-Bibliography Burns

159 CHAPTER 8 THE BRISBANE LINE CONTROVERSY Near the end of March 1943 nineteen members of the UAP demanded Billy Hughes call a party meeting. Hughes had maintained his hold over the party membership by the expedient of refusing to call members 1a together. For months he had then been able to avoid any leadership challenge. Hughes at last conceded to party pressure, and on 25 March, faced a leadership spill, which he believed was inspired by Menzies. 16 He retained the leadership by twenty-four votes to fifteen. The failure to elect a younger and more aggressive leader - Menzies - resulted in early April in the formation by the dissenters of the National Service Group, which was a splinter organisation, not a separate party. Menzies, and Senators Leckie and Spicer from Victoria, Cameron, Duncan, Price, Shcey and Senators McLeary, McBride, the McLachlans, Uphill and Wilson from South Australia, Beck and Senator Sampson from Tasmania, Harrison from New South Wales and Senator Collett from Western Australia comprised the group. Spender stood aloof. 1 This disturbed Ward. As a potential leader of the UAP Menzies was likely to be more of an electoral threat to the ALP, than Hughes, well past his prime, and in the eyes of the public a spent political force. Still, he was content to wait for the appropriate moment to discredit his old foe, confident he had the ammunition in his Brisbane Line claims. The Brisbane Line Controversy Ward managed to verify that a plan existed which had intended to abandon all of Australia north of a line north of Brisbane and following a diagonal course to a point north of Adelaide to be abandoned to the enemy, - the Maryborough Plan. -

Supplement 1

*^b THE BOOK OF THE STATES .\ • I January, 1949 "'Sto >c THE COUNCIL OF STATE'GOVERNMENTS CHICAGO • ••• • • ••'. •" • • • • • 1 ••• • • I* »• - • • . * • ^ • • • • • • 1 ( • 1* #* t 4 •• -• ', 1 • .1 :.• . -.' . • - •>»»'• • H- • f' ' • • • • J -•» J COPYRIGHT, 1949, BY THE COUNCIL OF STATE GOVERNMENTS jk •J . • ) • • • PBir/Tfili i;? THE'UNIfTED STATES OF AMERICA S\ A ' •• • FOREWORD 'he Book of the States, of which this volume is a supplement, is designed rto provide an authoritative source of information on-^state activities, administrations, legislatures, services, problems, and progressi It also reports on work done by the Council of State Governments, the cpm- missions on interstate cooperation, and other agencies concepned with intergovernmental problems. The present suppkinent to the 1948-1949 edition brings up to date, on the basis of information receivjed.from the states by the end of Novem ber, 1948^, the* names of the principal elective administrative officers of the states and of the members of their legislatures. Necessarily, most of the lists of legislators are unofficial, final certification hot having been possible so soon after the election of November 2. In some cases post election contests were pending;. However, every effort for accuracy has been made by state officials who provided the lists aiid by the CouncJLl_ of State Governments. » A second 1949. supplement, to be issued in July, will list appointive administrative officers in all the states, and also their elective officers and legislators, with any revisions of the. present rosters that may be required. ^ Thus the basic, biennial ^oo/t q/7^? States and its two supplements offer comprehensive information on the work of state governments, and current, convenient directories of the men and women who constitute those governments, both in their administrative organizations and in their legislatures. -

Neale Towart

The writer is the Heritage Officer and Librarian at Unions NSW, a role I have held for 24 years. I have continued the valuable work that Lorna Morrison, former secretary of the Sydney Trades Hall Association, began in the late 1960s to ensure the retention and development of trade union history in the building built specifically by and for trade union education. Unions NSW, via the Sydney Trades Hall, a heritage listed building, actively collects, conserves, displays and generally makes available to the public the largest collection of trade union memorabilia in Australia. This collection includes a trade union banner collection dating largely from 1890 to 1920, trade union badges dating from 1879, photographs, archives and newspapers and other memorabilia that are a core part of the history of working people and democracy in NSW and Australia. These are part of the reason the building is of national significance and the collection is recognised as key moveable heritage under NSW Heritage legislation. The importance is in its having been retained on site and that it is available to the public, be they researchers or visiting tourists. Since 1872 the Sydney Trades Hall Association and Unions NSW (through its preceding body the Sydney Labour Council) has seen the educational role as central to the role of Unions NSW and Sydney Trades Hall. A library and Literary Institute being a core function of the organisations since their beginnings. All unions that have been affiliated to Unions NSW and whom have had offices in the Trades Hall have availed themselves of the Library and education opportunities that unions have had as part of their role. -

The Final Campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year The final campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945 Karl James University of Wollongong James, Karl, The final campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945, PhD thesis, School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2005. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/467 This paper is posted at Research Online. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/467 The Final Campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy from University of Wollongong by Karl James, BA (Hons) School of History and Politics 2005 i CERTIFICATION I, Karl James, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, is wholly my work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Karl James 20 July 2005 ii Table of Contents Maps, List of Illustrations iv Abbreviations vi Conversion viii Abstract ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1 ‘We have got to play our part in it’. Australia’s land war until 1944. 15 2 ‘History written is history preserved’. History’s treatment of the Final Campaigns. 30 3 ‘Once the soldier had gone to war he looked for leadership’. The men of the II Australian Corps. 51 4 ‘Away to the north of Queensland, On the tropic shores of hell, Stand grimfaced men who watch and wait, For a future none can tell’. The campaign takes shape: Torokina and the Outer Islands. -

'Something Is Wrong with Our Army…' Command, Leadership & Italian

Journal of Military and Strategic VOLUME 14, ISSUE 1, FALL 2011 Studies ‘Something is wrong with our army…’ Command, Leadership & Italian Military Failure in the First Libyan Campaign, 1940-41. Dr. Craig Stockings There is no question that the First Libyan Campaign of 1940-41 was an Italian military disaster of the highest order. Within hours of Mussolini’s declaration of war British troops began launching a series of very successful raids by air, sea and land in the North African theatre. Despite such early setbacks a long-anticipated Italian invasion of Egypt began on 13 September 1940. After three days of ponderous and costly advance, elements of the Italian 10th Army halted 95 kilometres into Egyptian territory and dug into a series of fortified camps southwest of the small coastal village of Sidi Barrani. From 9-11 December, these camps were attacked by Western Desert Force (WDF) in the opening stages of Operation Compass – the British counter-offensive against the Italian invasion. Italian troops not killed or captured in the rout that followed began a desperate and disjointed withdrawal back over the Libyan border, with the British in pursuit. The next significant engagement of the campaign was at the port-village Bardia, 30 kilometres inside Libya, in the first week of 1941. There the Australian 6 Division, having recently replaced 4 Indian Division as the infantry component of WDF (now renamed 13 Corps), broke the Italian fortress and its 40,000 defenders with few casualties. The feat was repeated at the port of Tobruk, deeper into Libya, when another 27,000 Italian prisoners were taken.