Blessed Mythmaker 12-19 Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

18 Korach Email Draft

ה“ב ע ר ש “ ק פ ר ש ת ק ר ח “כ, ב ס י ו ן , ת ש ע א“ VOLUME 1, ISSUE 18 INSIDE THIS A Visit to the Ohel - Rostov 5685 I S S U E : As Gimmel Tammuz approaches, we found it Leben Miten Rebben 1 The Rebbe handed me a packet of Panim and appropriate to quote the following section from the memoirs instructed that I only place them on the Ohel of Horav Yisroel Jacobson . It was in the year 5685 without reading them at all beforehand. Whereas Serpa Pinto 2 (1925), shortly after the rise of the Communist regime in his own personal Pan , I was to read only once and Russia when the Frierdiker Rebbe appointed him as his only upon reaching the Ohel, no earlier. I was personal Shliach to visit the Ohel of the Rebbe Rashab in Niggun — 3 absolutely forbidden to show it to anyone else or Alter Rebbe’s Niggunim Rostov on his Yahrtzei, Beis Nissan. From the words of the Frierdiker Rebbe in that Yechidus, we learn much about the to copy it down; no exceptions! (When I did read Biography - 3 significance of a Chossid visiting the Rebbe's Ohel, in it's it, I noticed that in the first section he requested Reb Berke Chein – 5 being not merely a stop at Kivrei Tzadikim (Chas Brochos for himself personally as a Rebbe, and Q&A - 4 V'Sholom), but an actual Yechidus with the Rebbe. (In the later as a leader of world Jewry, he mentioned and Learning Gemara following excerpt, "the Rebbe" refers to the Frierdiker articulated many of the problems encountering the Rebbe). -

Founder of Hasidism: a Quest for the Historical Baal Shem Tov PDF Book

FOUNDER OF HASIDISM: A QUEST FOR THE HISTORICAL BAAL SHEM TOV PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Author Moshe Rosman | 352 pages | 20 Jun 2013 | The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization | 9781906764449 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom Founder of Hasidism: A Quest for the Historical Baal Shem Tov PDF Book All Rights Reserved. Areas of Sabbatian, Frankist, and Beshtian activity, eighteenth century. But the Satan the angel representing the innermost source of darkness became very angry because such a spiritual uplifting was interfering with his work. His teachings imbued the esoteric usage of practical Kabbalah of Baalei Shem into a spiritual movement, Hasidic Judaism. And love every Jew dearly. Some began to run away, and some were frozen in terror. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Other editions. Download as PDF Printable version. It is reported that, after the conclusion of his studies at the local cheder Jewish elementary school , he would often wander into the fields and forests that surrounded the village. A Country in Decline? And so it was! For the next several years he lived with different families, moving from one home to another. The Besht: Magician, Mystic, and Leader. Light from the Archives. Suzan Sunderland marked it as to-read Oct 21, The werewolf appeared to grow larger and larger and then started snorting and pawing the ground. He based this belief on the assumption that the letters of the Torah evolved and descended from a heavenly source, and therefore by contemplating the letters, one can restore them to their spiritual, and divine source. In the bet midrash, the Besht led his circle in kabbalistic rituals, such as adding special prayers kavanot to the normal prayer ritual. -

Tzadik Righteous One", Pl

Tzadik righteous one", pl. tzadikim [tsadi" , צדיק :Tzadik/Zadik/Sadiq [tsaˈdik] (Hebrew ,ṣadiqim) is a title in Judaism given to people considered righteous צדיקים [kimˈ such as Biblical figures and later spiritual masters. The root of the word ṣadiq, is ṣ-d- tzedek), which means "justice" or "righteousness". The feminine term for a צדק) q righteous person is tzadeikes/tzaddeket. Tzadik is also the root of the word tzedakah ('charity', literally 'righteousness'). The term tzadik "righteous", and its associated meanings, developed in Rabbinic thought from its Talmudic contrast with hasid ("pious" honorific), to its exploration in Ethical literature, and its esoteric spiritualisation in Kabbalah. Since the late 17th century, in Hasidic Judaism, the institution of the mystical tzadik as a divine channel assumed central importance, combining popularization of (hands- on) Jewish mysticism with social movement for the first time.[1] Adapting former Kabbalistic theosophical terminology, Hasidic thought internalised mystical Joseph interprets Pharaoh's Dream experience, emphasising deveikut attachment to its Rebbe leadership, who embody (Genesis 41:15–41). Of the Biblical and channel the Divine flow of blessing to the world.[2] figures in Judaism, Yosef is customarily called the Tzadik. Where the Patriarchs lived supernally as shepherds, the quality of righteousness contrasts most in Contents Joseph's holiness amidst foreign worldliness. In Kabbalah, Joseph Etymology embodies the Sephirah of Yesod, The nature of the Tzadik the lower descending -

Global Antisemitism: a Crisis of Modernity

GLOBAL ANTISEMITISM: A CRISIS OF MODERNITY Volume II The Intellectual Environment Charles Asher Small Editor ISGAP © 2013 INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF GLOBAL ANTISEMITISM AND POLICY Honorary President Professor Elie Wiesel Director Charles Asher Small Co-Chairs of the International Academic Board of Advisors Professor Irwin Cotler Professor Alan Dershowitz ISGAP Europe – Coordinator Robert Hassan ISGAP Asia – Chair Jesse Friedlander Publications Consultant Alan Stephens Administrative Coordinator Jenny Pigott ISGAP 165 East 56th Street, 2nd Floor New York, New York 10022 Phone: 212-230-1840 Fax: 212-230-1842 www.isgap.org The opinions expressed in this work are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy, its officers or the members of its Boards. Cover by Romijn Design Layout by AETS Printing and binding by Graphos Print ISBN 978 1 940186 02 3 (paperback) ISBN 978 1 940186 03 0 (eBook) For Professor William Prusoff About the Editor Dr. Charles Asher Small is the Director of the Institute for the Study of Global Anti- semitism and Policy (ISGAP). He is also the Koret Distinguished Scholar at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University. Charles received his Bachelor of Arts in Political Sci- ence, McGill University, Montreal; a M.Sc. in Urban Development Planning in Econom- ics, Development Planning Unit (DPU), University College London; and a Doctorate of Philosophy (D.Phil), St. Antony’s College, Oxford University. Charles completed post-doctorate research at the Groupement de recherche ethnicité et société, Université de Montréal. He was the VATAT Research Fellow (Ministry of Higher Education) at Ben Gurion University, Beersheva, and taught in departments of sociology and geography at Goldsmiths’ College, University of London; Tel Aviv University; and the Institute of Urban Studies, Hebrew University, Jerusalem. -

The Great Maggid

Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov was bom on the 18th of Elul 5458 ( 1698) in Okup, a small border-town between the Vol- hynia and Podolia districts in Russia/ At a young age he joined up with a group of itinerant Nistarim, a group of mystics who concealed their identities and secretly pursued the study and application of the tenets of Jewish mysticism. There were many groups of these mystics, often referred to as Tzadikim Nistarim (anonymous saints).* Originally they made it their task to pursue and promulgate the teachings of the Cabbalah. In the wake of the calamitous events of the persecutions and pogroms of the seventeenth century, and the tragic conseQuences of the pseudo-messianic movement of Shabatay Tzvi and his followers. 1. See J. I. Scbodiet, Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov, chapter IV, p. 35, and notes 1 and 3 ad loc. 2. Ibid., chapter II, p. 28. An organized society of Nistarim is said to have been founded by Rabbi Elijah Baal Shem of Worms (not to be confused with Rabbi Elijah Loans who also is known as 'Baal Shem of Worms'), a Cabbalist whose father. Rabbi Joseph Juspa, was of the refugees expelled from Spain in 1492. See more on him, his activities and his society of Nistarim, in Sefer Hazichronos (Memoirs of Rabbi Joseph Isaac Schneersohn of Lubavitch, 2 volumes; Yiddish edition. New York: Kehot 1955-65; English edition New York: Kdiot 1956 60). A nundjer of the Baal Shem Tov’s associates and disciples original ly were members of this or similar groups of Nistarim and allusions to them may be found in Shivchei Habesht and other wmrks relating to that p e ri^ of time. -

BTT Parashat Bereshit-2015

Bits of Torah Truths Simchat Torah Series פרשת בראשית Bereshit / Genesis 1:1-6:8, Isaiah 42:5-43:10 John 1:1-18 ereshit Parashat Bereshit Parashat B The Beginning of God’s Creative Work is Separating the Righteous from the Unrighteous This week’s reading from Parashat Bereshit (Bereshit / Genesis 1:1- 6:8) contains some of the most significant actions of God, which set the stage for all of Scripture. More specifically, we are told the first thing the Lord does in His creation, is to separate the light from the darkness. What is the significance of the Lord beginning His creative process by separat- ing the light from the darkness? Is it possible, in this description of the creation events, the Lord God is laying the foundation for not only the definition of a day, but to say that the beginning of His ways is to make a distinction between light and darkness, as an illustration for the begin- ning of His work in our lives to make a distinction between righteousness and unrighteousness? In the creation account in Bereshit / Genesis 1, the Lord describes the separating between the light and the darkness, as day and night, and that it is very good. He specifically calls the light“good,” but not state the darkness is good. The following verses adds additional context to the separation process. Bereshit / Genesis 1:6-8 1:6 Then God said, ‘Let there be an expanse in the midst of the waters, and let it separate the waters from the wa- ters.’ 1:7 God made the expanse, and separated the waters which were below the expanse from the waters which were above the expanse; and it was so. -

YAM Summer Program

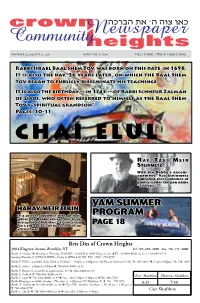

1 CROWN HEIGHTS NewsPAPER ~September 12, 2008 כאן צוה ה’ את הברכה CommunityNewspaper פרשת כי תצא | יב' אלול , תשס”ח | בס”ד WEEKLY VOL. I | NO 43 SEPTEMBER 12, 2008 | ELUL 12, 5768 Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov, was born on this date, in 1698. It is also the day, 36 years later, on which the Baal Shem Tov began to publicly disseminate his teachings. It is also the birthday -- in 1745 -- of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, who often referred to himself as the Baal Shem Tov's "spiritual grandson" Pages: 10-11 CHAI ELUL R AV TZVI MEIR STEINMETZ With the Rebbe’s encour- agement, Rav Steinmetz published three volumes of poetry. under the pen name “Tzvi Yair.”. YAM SUMMER HARAV MEIR ITKIN In a private audience with an indi- PROGRAM vidual, the Rebbe advised him to go and speak to Reb Meir, “Er vais vi tzu PAGE 18 ton a Yid a toiva”, he knows how to do a Yid a favor. Beis Din of Crown Heights 390A Kingston Avenue, Brooklyn, NY Tel- 718~604~8000 Fax: 718~771~6000 Rabbi A. Osdoba: ❖ Monday to Thursday 10:30AM - 11:30AM at 390A Kingston Ave. ☎Tel. 718-604-8000 ext.37 or 718-604-0770 Sunday-Thursday 9:30 PM-11:00PM ~Friday 2:30PM-4:30 PM ☎Tel. (718) - 771-8737 Rabbi Y. Heller is available daily 10:30 to 11:30am ~ 2:00pm to 3:00pm at 788 Eastern Parkway # 210 718~604~8827 ❖ & after 8:00pm 718~756~4632 Rabbi Y. Schwei, 4:00pm to 9:00pm ❖ 718~604~8000 ext 36 Rabbi Y. -

March 2020 3 HOLIDAYS @ ADAS HOLIDAYS @ ADAS

Adas Israel Congregation • March/Adar-Nisan 5780 C TheHRONICLE Chronicle Is Supported in Part by the Ethel and Nat Popick Endowment Fund THE STORM PuRIM @ ADAS OUR VOICES INTRODUCING ADAS' NEW PODCAST: AWAKE Clergy Corner WITH RABBI LAUREN HOLTZBLATT RABBI AARON ALEXANDER Awake: Finding the Holy in the Everyday In this new podcast, Rabbi Holtzblatt will bring the teachings from Jewish mystical texts and the Hasidic masters from the 13th-20th century into everyday Same, Different, Transformed AWAKE life. The podcast will offer a few minutes to pause WITH RABBI LAUREN HOLTZBLATT and to open ourselves to the possibility that holiness, connection and presence are around us all of the time. You've probably noticed that over the last few years that Purim irreverent, and off-the-wall upside--downness. In other words, has become like a mini-High Holiday here at Adas. Over the even our most serious expressions of religiousity need a new course of the evning the building fills up with every possible angle of discovery every once in a while. Hence the costumes, demographic this community experiences over the course of shticks, pranks, and specially the laughing at ourselves. In this the year. We pay close attention to the physical space of Adas, way, Mary Poppins perfectly captured the upcoming holiday and thoughtfully transforming it in an attempt to allow its versatility the way we observe it here: “WHEN THE WORLD TURNS UPSIDE "How do we stop and notice that incredible, to signifcantly impact the way in which we experience the DOWN, THE BEST THING TO DO IS TURN RIGHT ALONG WITH HOW TO LISTEN holiday together. -

Founder of Hasidism: a Quest for the Historical Baal Shem Tov Pdf, Epub, Ebook

FOUNDER OF HASIDISM: A QUEST FOR THE HISTORICAL BAAL SHEM TOV PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Author Moshe Rosman | 352 pages | 20 Jun 2013 | The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization | 9781906764449 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom Founder of Hasidism: A Quest for the Historical Baal Shem Tov PDF Book Besht himself is still the real center for the Hasidim; his teachings have almost sunk into oblivion. Rosman's study casts a bright new light on the traditional stories about the Besht, confirming and augmenting some, challenging others. Some aspects of his medical practice are said to have been mystic in nature, though the degree to which this is the case is not agreed upon. The Jewish Encyclopedia. First of all, these stories are not to be limited to the Baal Shem Tov, but should include tales of all our Tzaddikim. Patrick Cook marked it as to-read Feb 05, The middle of Rosman's book focuses on a few letters written by and to the Besht himself. As always, the children were singing, but were very apprehensive, walking through the fields faster than usual, afraid that the werewolf would make his return. Judaism portal. Jeff Kuperman added it Aug 28, Moshe Rosman. Let, on the contrary, friendship, peace, and harmony prevail between me and the physicians,. Some claim [ Like whom? Lists with This Book. Gavin marked it as to-read Jul 09, Within this context, the Jews of Podolia were open to new ideas. This view is derived from a series of titles given to the Besht, attributing various religious achievements unto him such as understanding the mysteries of God. -

Federation Maimonides Society to Sponsor Stem Cell Symposium Avram Kluger, Special to the WJN N Sunday, February 13, at 9:30 A.M., at 10:15 A.M

Washtenaw Jewish News Presort Standard In this issue… c/o Jewish Federation of Greater Ann Arbor U.S. Postage PAID 2939 Birch Hollow Drive Ann Arbor, MI Ann Arbor, MI 48108 Frankel Jewish Israel Permit No. 85 Center Camping Scholarship Belin Essays Lecture Page 3 Page 14 Page 20 February 2011 Shevat/Adar 5771 Volume XXXV: Number 5 FREE Federation Maimonides Society to sponsor stem cell symposium Avram Kluger, special to the WJN n Sunday, February 13, at 9:30 a.m., at 10:15 a.m. The to write a systemic code of Jewish law, the Mish- the Maimonides Society of the Jew- breakfast and neh Torah. Trained as a physician, he served as O ish Federation of Greater Ann Arbor program are un- court physician to the sultan of Egypt and wrote will host a symposium entitled “The Stem Cell derwritten by a many books on medicine. He served as leader of Story: Facts, Fictions and Legalities” at the Uni- generous grant the Cairo Jewish community. versity of Michigan Kellogg Eye Center, located from Fifth Third The Ann Arbor Maimonides Society has at 1000 Wall Street. Bank. hosted programs designed to appeal to broad The symposium, which is free and open to The Maimo- community interests. Recent events have fea- the public, will explore the medicine, ethics, the nides Society of tured Richard Lichtenstein, PhD, on faults of law, and politics of the stem cell debate. Featured the Jewish Fed- the U.S. health care system; David Pinsky, MD, presenters will include Ivan Maillard, MD, PhD; eration of Greater on advances in cardiac care; Sidney Wolfe, MD, Edward Goldman, JD; and Gerry Hoehn, PhD. -

Jan/Feb 2020

The tar S NEWSLETTER TEVET/SH’VAT/ADAR 5780 January/ February 2020 VOL. 23 NO. 1 TEMPLE BETH TORAH, 130 MAIN STREET WETHERSFIELD, CONNECTICUT Tu biShvat Message from Rabbi Seth Riemer Co-Presidents Message ill you and I listen to Greta Thunberg’s vehement come to the one we’re holding on Sunday, February 9 at ello TBT family and a very Healthy and Happy New Year to all of you! Lots of events are on our calendar for the coming year. Wdeclaration, “Our house is on fire”? She is stating the 10:00 am) conceived of four worlds: earthy (physical), H obvious. Australia is literally burning, and you surely watery (emotional), airy (mental) and fiery (spiritual). We ended 2019 with our very successful Chanukah Party. 31 people joined to- have observed, here in Connecticut, the freakish oc- Greta Thunberg’s passionate delivery channels some gether to feast on latkes, egg and tuna salad, home-made challah, and a plethora of desserts! Special thanks to all who helped with the food preparation, set-up currence of people walking around in shorts and tee- of the same fire that inspired Moses, but she might not and clean-up. Te Menorah lighting was lovely. So many families joined together shirts in January. Profiting in the moment from our recognize her fire as an ultimate well-spring—a river to light their menorahs. It was wonderful to see the Chanukah lights refecting on contemporary “throw-away” culture’s shortsightedness, of light—behind spiritual devotion that can transform so many happy faces! It was also nice to see our TBT menorah built by Ralph and we seem to be letting the world slip away. -

Global Antisemitism: a Crisis of Modernity

GLOBAL ANTISEMITISM: A CRISIS OF MODERNITY Volume V Reflections Charles Asher Small Editor ISGAP © 2013 INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF GLOBAL ANTISEMITISM AND POLICY Honorary President Professor Elie Wiesel Director Charles Asher Small Co-Chairs of the International Academic Board of Advisors Professor Irwin Cotler Professor Alan Dershowitz ISGAP Europe – Coordinator Robert Hassan ISGAP Asia – Chair Jesse Friedlander Publications Consultant Alan Stephens Administrative Coordinator Jenny Pigott ISGAP 165 East 56th Street, 2nd Floor New York, New York 10022 Phone: 212-230-1840 Fax: 212-230-1842 www.isgap.org The opinions expressed in this work are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy, its officers or the members of its Boards. Cover by Romijn Design Layout by AETS Printing and binding by Graphos Print ISBN 978 1 940186 08 5 (paperback) ISBN 978 1 940186 09 2 (eBook) For Professor William Prusoff About the Editor Dr. Charles Asher Small is the Director of the Institute for the Study of Global Anti- semitism and Policy (ISGAP). He is also the Koret Distinguished Scholar at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University. Charles received his Bachelor of Arts in Political Sci- ence, McGill University, Montreal; a M.Sc. in Urban Development Planning in Econom- ics, Development Planning Unit (DPU), University College London; and a Doctorate of Philosophy (D.Phil), St. Antony’s College, Oxford University. Charles completed post-doctorate research at the Groupement de recherche ethnicité et société, Université de Montréal. He was the VATAT Research Fellow (Ministry of Higher Education) at Ben Gurion University, Beersheva, and taught in departments of sociology and geography at Goldsmiths’ College, University of London; Tel Aviv University; and the Institute of Urban Studies, Hebrew University, Jerusalem.