Global Antisemitism: a Crisis of Modernity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Holocaust and World War II

The Holocaust and World War II The Holocaust and World War II: In History and In Memory Edited by Nancy E. Rupprecht and Wendy Koenig The Holocaust and World War II: In History and In Memory, Edited by Nancy E. Rupprecht and Wendy Koenig This book first published 2012 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2012 by Nancy E. Rupprecht and Wendy Koenig and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-4126-9, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-4126-9 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part I: Introduction Chapter One................................................................................................. 2 Introduction Nancy E. Rupprecht and Wendy Koenig Part II: Brief Histories Chapter Two.............................................................................................. 14 World War II: A Brief History Gerhard L. Weinberg Chapter Three............................................................................................ 43 The Holocaust: A Brief History Nancy E. Rupprecht Part III: History As It Was Lived Chapter Four.............................................................................................. 76 Roosevelt, -

Farrakhan Talks to the Jews

JEWISH WORLD COVER STORY Farrakhan Talks to the Jews For three hours, over colfee in his home, Nation oj Islam leader Louis Farrakhan spoke to the Jewish people through The Jerusalem Report. The anti-Semitism he repeatedly spouts was no less virulent at his dining room table, but his message "is Jor the Jews' own good." VINCE BEISER Chicago HATEVER ELSE WUIS White House, he has called it. have publicly called for the community to Farrakhan may be, let "I want you to feel at home, and ask any take Farrakhan up on his repeated ap no one say he is not a questions you feel your readers would be peals for a meeting with Jewish leaders. gracious host - even interested in," says Farrakhan, his voice Last year, at the urging of Jewish "60 to a Jewish j ournalist. as honey-smooth as a Motown Singer. One Minutes" journalist Mike Wallace, World Before beginning our reason he has become perhaps the na Jewish Congress head Edgar Bronfman interview at his palatial residence in an tion's most important African-American hosted Farrakhan and his wife at a dinner affluent, integrated South Chicago neigh leader is immediately obvious: The man in his New York home (although Bronf borhood, the leader of the Nation of Islam practically glows with charisma and man soon cut off contact with the minis- ter). And in April Edward Rendell, Philadelphia's Jew ish mayor, invited the minis 'I PLEDGE THIS to you. I have no intention whatsoever ter to speak at a rally to promote racial healing. -

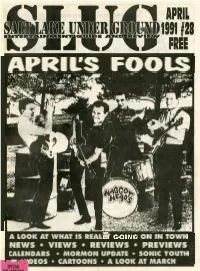

April's Fools

APRIL'S FOOLS ' A LOOK AT WHAT IS REAL f ( i ON IN. TOWN NEWS VIEWS . REVIEWS PREVIEWS CALENDARS MORMON UPDATE SONIC YOUTH -"'DEOS CARTOONS A LOOK AT MARCH frlday, april5 $7 NOMEANSNO, vlcnms FAMILYI POWERSLAVI saturday, april 6 $5 an 1 1 piece ska bcnd from cdlfomb SPECKS witb SWlM HERSCHEL SWIM & sunday,aprll7 $5 from washln on d.c. m JAWBO%, THE STENCH wednesday, aprl10 KRWTOR, BLITZPEER, MMGOTH tMets $10raunch, hemmetal shoD I SUNDAY. APRIL 7 I INgTtD, REALITY, S- saturday. aprll $5 -1 - from bs aqdes, califomla HARUM SCAIUM, MAG&EADS,;~ monday. aprlll5 free 4-8. MAtERldl ISSUE, IDAHO SYNDROME wedn apri 17 $5 DO^ MEAN MAYBE, SPOT fiday. am 19 $4 STILL UFEI ALCOHOL DEATH saturday, april20 $4 SHADOWPLAY gooah TBA mday, 26 Ih. rlrdwuhr tour from a land N~AWDEATH, ~O~LESH;NOCTURNUS tickets $10 heavy metal shop, raunch MATERIAL ISSUE I -PRIL 15 I comina in mayP8 TFL, TREE PEOPLE, SLaM SUZANNE, ALL, UFT INSANE WARLOCK PINCHERS, MORE MONDAY, APRIL 29 I DEAR DICKHEADS k My fellow Americans, though:~eopledo jump around and just as innowtiwe, do your thing let and CLIJG ~~t of a to NW slam like they're at a punk show. otherf do theirs, you sounded almost as ENTEIWAINMENT man for hispoeitivereviewof SWIM Unfortunately in Utah, people seem kd as L.L. "Cwl Guy" Smith. If you. GUIIBE ANIB HERSCHELSWIMsdebutecassette. to think that if the music is fast, you are that serious, I imagine we will see I'mnotamemberofthebancljustan have to slam, but we're doing our you and your clan at The Specks on IMVIEW avid ska fan, and it's nice to know best to teach the kids to skank cor- Sahcr+nightgiwingskrmkin'Jessom. -

ISSUE 1820 AUGUST 17, 1990 BREATHE "Say Aprayer"9-4: - the New Single

ISSUE 1820 AUGUST 17, 1990 BREATHE "say aprayer"9-4: - the new single. Your prayers are answered. Breathe's gold debut album All That Jazz delivered three Top 10 singles, two #1 AC tracks, and songwriters David Glasper and Marcus Lillington jumped onto Billboard's list of Top Songwriters of 1989. "Say A Prayer" is the first single from Breathe's much -anticipated new album Peace Of Mind. Produced by Bob Sargeant and Breathe Mixed by Julian Mendelsohn Additional Production and Remix by Daniel Abraham for White Falcon Productions Management: Jonny Too Bad and Paul King RECORDS I990 A&M Record, loc. All rights reserved_ the GAVIN REPORT GAVIN AT A GLANCE * Indicates Tie MOST ADDED MOST ADDED MOST ADDED MOST ADDED MICHAEL BOLTON JOHNNY GILL MICHAEL BOLTON MATRACA BERG Georgia On My Mind (Columbia) Fairweather Friend (Motown) Georgia On My Mind (Columbia) The Things You Left Undone (RCA) BREATHE QUINCY JONES featuring SIEDAH M.C. HAMMER MARTY STUART Say A Prayer (A&M) GARRETT Have You Seen Her (Capitol) Western Girls (MCA) LISA STANSFIELD I Don't Go For That ((west/ BASIA HANK WILLIAMS, JR. This Is The Right Time (Arista) Warner Bros.) Until You Come Back To Me (Epic) Man To Man (Warner Bros./Curb) TRACIE SPENCER Save Your Love (Capitol) RECORD TO WATCH RECORD TO WATCH RECORD TO WATCH RECORD TO WATCH RIGHTEOUS BROTHERS SAMUELLE M.C. HAMMER MARTY STUART Unchained Melody (Verve/Polydor) So You Like What You See (Atlantic) Have You Seen Her (Capitol) Western Girls (MCA) 1IrPHIL COLLINS PEBBLES ePHIL COLLINS goGARTH BROOKS Something Happened 1 -

Australia Muslim Advocacy Network

1. The Australian Muslim Advocacy Network (AMAN) welcomes the opportunity to input to the UN Special Rapporteur on the Freedom of Religion or Belief as he prepares this report on the Impact of Islamophobia/anti-Muslim hatred and discrimination on the right to freedom of thought, conscience religion or belief. 2. We also welcome the opportunity to participate in your Asia-Pacific Consultation and hear from the experiences of a variety of other Muslims organisations. 3. AMAN is a national body that works through law, policy, research and media, to secure the physical and psychological welfare of Australian Muslims. 4. Our objective to create conditions for the safe exercise of our faith and preservation of faith- based identity, both of which are under persistent pressure from vilification, discrimination and disinformation. 5. We are engaged in policy development across hate crime & vilification laws, online safety, disinformation and democracy. Through using a combination of media, law, research, and direct engagement with decision making parties such as government and digital platforms, we are in a constant process of generating and testing constructive proposals. We also test existing civil and criminal laws to push back against the mainstreaming of hate, and examine whether those laws are fit for purpose. Most recently, we are finalising significant research into how anti-Muslim dehumanising discourse operates on Facebook and Twitter, and the assessment framework that could be used to competently and consistently assess hate actors. A. Definitions What is your working definition of anti-Muslim hatred and/or Islamophobia? What are the advantages and potential pitfalls of such definitions? 6. -

The Great Escape: How and Why Most Arab States Became Judenfrei

The Great Escape: How and Why Most Arab States Became Judenfrei Byline: Dr. Peter Schotten The Great Escape: How and Why Most Arab States Became Judenfrei By Peter Schotten Dr. Peter Schotten is emeritus professor of Government and International Affairs at Augustana University (Sioux Falls, South Dakota). Review Essay: Lyn Julius, Uprooted: How 3000 Years of Jewish Civilization in the Arab World Vanished Overnight (London: Vallentine Mitchell, 2018). Other Books Discussed: Martin Gilbert, A History of Jews in Muslim Lands (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010). Joshua Muravchik, Making David into Goliath: How the World Turned Against Israel (New York: Encounter Books, 2014). Israel has become a victim of its own success. Initially, Its 1948 founding was celebrated by much of the western world. Israel's modern realization represented a triumph of heroic tenacity as well as the advancement of the laudable political principles of freedom and self-determination. Even more important, Israel's newly won statehood proudly proclaimed the survival of a Judaism that had faced extinction from an unfathomable Nazi evil. The early flourishing of the Israeli political and economic experiment, especially after its first days when it fought and won a war of national survival against numerous Arab nations, proved as improbable as its founding. Despite a bevy of predictable social, economic and political challenges, a fair-minded observer of Israel's early history and world standing would conclude that everything, or nearly everything crucial, had gone right. Of course it was all too good to last. Seventy years later, Israel continues to prosper amidst serious obstacles in one of the world's toughest neighborhoods. -

Holocaust-Denial Literature: a Fourth Bibliography

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research York College 2000 Holocaust-Denial Literature: A Fourth Bibliography John A. Drobnicki CUNY York College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/yc_pubs/25 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Holocaust-Denial Literature: A Fourth Bibliography John A. Drobnicki This bibliography is a supplement to three earlier ones published in the March 1994, Decem- ber 1996, and September 1998 issues of the Bulletin of Bibliography. During the intervening time. Holocaust revisionism has continued to be discussed both in the scholarly literature and in the mainstream press, especially owing to the libel lawsuit filed by David Irving against Deb- orah Lipstadt and Penguin Books. The Holocaust deniers, who prefer to call themselves “revi- sionists” in an attempt to gain scholarly legitimacy, have refused to go away and remain as vocal as ever— Bradley R. Smith has continued to send revisionist advertisements to college newspapers (including free issues of his new publication. The Revisionist), generating public- ity for his cause. Holocaust-denial, which will be used interchangeably with Holocaust revisionism in this bib- liography, is a body of literature that seeks to “prove” that the Jewish Holocaust did not hap- pen. Although individual revisionists may have different motives and beliefs, they all share at least one point: that there was no systematic attempt by Nazi Germany to exterminate Euro- pean Jewry. -

Halakhic Process 25 – Open Orthodoxy Sources

Halakhic Process Open Orthodoxy I. The Values of Open Orthodoxy 1. R. Avi Weiss – From Spiritual Activism Perhaps the most fundamental principle in Judaism is that every person is created in the image of God (Gen. 1:27). Just as God gives and cares, so too do we – in the spirit of imitation Dei, "imitating god" – have the natural capacity to be giving and caring. In utilizing this capability, we reflect how God works through people. It is these spiritual underpinnings that are so crucial in carrying out political activism in the moral and ethical realms. The challenge for activists is to ignite the divine spark present in the human spirit and thereby impel people to do good for others. (P. XVIII) 2. R. Avi Weiss – From Women at Prayer A second area of development, concerns the view of Rav Yosef Dov Halevi Soloveitchik zt"l. In a recent article in Tradition by Rabbis Aryeh and Dov Frimer, they concluded that while the Rav did not criticize these groups from a technical halakhic perspective, he had serious public policy concerns about them. The Rav himself, always encouraged me and my colleagues in the rabbinate to pasken for our respective communities on these matters, for he realized that it is the individual Rav who has the responsibility to decide what is best for his community, as he often knows what is best for his constituency. This was the position of Rav Moshe Feinstein, as his grandson Rabbi Mordechai Tendler confirmed to me about two years ago. In any event, as Rav Aaron Soloveitchik has pointed out, public policy can be fluid, and what was a bad policy years ago might now be beneficial, or the contrary. -

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds an End to Antisemitism!

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds An End to Antisemitism! Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman Volume 5 Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman ISBN 978-3-11-058243-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-067196-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-067203-9 DOI https://10.1515/9783110671964 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Library of Congress Control Number: 2021931477 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, Lawrence H. Schiffman, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com Cover image: Illustration by Tayler Culligan (https://dribbble.com/taylerculligan). With friendly permission of Chicago Booth Review. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com TableofContents Preface and Acknowledgements IX LisaJacobs, Armin Lange, and Kerstin Mayerhofer Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds: Introduction 1 Confronting Antisemitism through Critical Reflection/Approaches -

E Conspiracy Eory to Rule Em

8/23/2020 The Conspiracy Theory to Rule Them All - The Atlantic Give a Gift e Conspiracy eory to Rule em All What explains the strange, long life of e Protocols of the Elders of Zion? Tereza Zelenkova Story by Steven J. Zipperstein NONE SHADOWLAND Like The Atlantic? Subscribe to The Atlantic Daily, our free weekday email newsletter. Enter your email Sign up Photography by Tereza Zelenkova https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/1857/11/conspiracy-theory-rule-them-all/615550/?preview=TcuaT5ZaZmqDeMMyDONAXVilKqE 1/8 8/23/2020 The Conspiracy Theory to Rule Them All - The Atlantic is article is part of “Shadowland,” a project about conspiracy thinking in America. ’ most consequential conspiracy text entered the world barely noticed, when it appeared in a little-read Russian newspaper in T 1903. The message of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion is straightforward, and terrifying: The rise of liberalism had provided Jews with the tools to destroy institutions—the nobility, the church, the sanctity of marriage—whole. Soon, they would take control of the world, as part of a revenge plot dating back to the ascendancy of Christendom. The text, ostensibly narrated by a Jewish leader, describes this plan in detail, relying on centuries-old anti-Jewish tropes, and including lengthy expositions on monetary, media, and electoral manipulation. It announces Jewry’s triumph as imminent: The world order will fall into the hands of a cunning elite, who have schemed forever and are now fated to rule until the end of time. It was a fabrication, and a clumsy one, largely copied from the obscure, French- language political satire Dialogue aux enfers entre Machiavel et Montesquieu, or The Dialogue in Hell Between Machiavelli and Montesquieu, by Maurice Joly. -

Understanding the Qanon Conspiracy from the Perspective of Canonical Information

The Gospel According to Q: Understanding the QAnon Conspiracy from the Perspective of Canonical Information Max Aliapoulios*;y, Antonis Papasavva∗;z, Cameron Ballardy, Emiliano De Cristofaroz, Gianluca Stringhini, Savvas Zannettou◦, and Jeremy Blackburn∓ yNew York University, zUniversity College London, Boston University, ◦Max Planck Institute for Informatics, ∓Binghamton University [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] — iDRAMA, https://idrama.science — Abstract administration of a vaccine [54]. Some of these theories can threaten democracy itself [46, 50]; e.g., Pizzagate emerged The QAnon conspiracy theory claims that a cabal of (literally) during the 2016 US Presidential elections and claimed that blood-thirsty politicians and media personalities are engaged Hillary Clinton was involved in a pedophile ring [51]. in a war to destroy society. By interpreting cryptic “drops” of A specific example of the negative consequences social me- information from an anonymous insider calling themself Q, dia can have is the QAnon conspiracy theory. It originated on adherents of the conspiracy theory believe that Donald Trump the Politically Incorrect Board (/pol/) of the anonymous im- is leading them in an active fight against this cabal. QAnon ageboard 4chan via a series of posts from a user going by the has been covered extensively by the media, as its adherents nickname Q. Claiming to be a US government official, Q de- have been involved in multiple violent acts, including the Jan- scribed a vast conspiracy of actors who have infiltrated the US uary 6th, 2021 seditious storming of the US Capitol building. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas.