Integrated Wireless Network

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEXT GENERATION MOBILE WIRELESS NETWORKS: 5G CELLULAR INFRASTRUCTURE JULY-SEPT 2020 the Journal of Technology, Management, and Applied Engineering

VOLUME 36, NUMBER 3 July-September 2020 Article Page 2 References Page 17 Next Generation Mobile Wireless Networks: Authors Dr. Rendong Bai 5G Cellular Infrastructure Associate Professor Dept. of Applied Engineering & Technology Eastern Kentucky University Dr. Vigs Chandra Professor and Coordinator Cyber Systems Technology Programs Dept. of Applied Engineering & Technology Eastern Kentucky University Dr. Ray Richardson Professor Dept. of Applied Engineering & Technology Eastern Kentucky University Dr. Peter Ping Liu Professor and Interim Chair School of Technology Eastern Illinois University Keywords: The Journal of Technology, Management, and Applied Engineering© is an official Mobile Networks; 5G Wireless; Internet of Things; publication of the Association of Technology, Management, and Applied Millimeter Waves; Beamforming; Small Cells; Wi-Fi 6 Engineering, Copyright 2020 ATMAE 701 Exposition Place Suite 206 SUBMITTED FOR PEER – REFEREED Raleigh, NC 27615 www. atmae.org JULY-SEPT 2020 The Journal of Technology, Management, and Applied Engineering Next Generation Mobile Wireless Networks: Dr. Rendong Bai is an Associate 5G Cellular Infrastructure Professor in the Department of Applied Engineering and Technology at Eastern Kentucky University. From 2008 to 2018, ABSTRACT he served as an Assistant/ The requirement for wireless network speed and capacity is growing dramatically. A significant amount Associate Professor at Eastern of data will be mobile and transmitted among phones and Internet of things (IoT) devices. The current Illinois University. He received 4G wireless technology provides reasonably high data rates and video streaming capabilities. However, his B.S. degree in aircraft the incremental improvements on current 4G networks will not satisfy the ever-growing demands of manufacturing engineering users and applications. -

Manual Connect.Pdf

Wireless computer access at K-State Information Technology Services provides wireless access across campus for both the K-State community and for campus visitors. Instructions for connecting to KSU Wireless Windows XP configuration Windows Vista configuration Windows 7 configuration Macintosh OS 10.5x/6 configuration Android configuration iPhone, iPad, or iPod Touch configuration HP Touch Pad configuration Chromebook configuration Ubuntu configuration Who can use K-State’s wireless network? 1. K-State faculty/staff and students should use “KSU Wireless”. 2. Residents in K-State residence halls and Jardine Apartments should use “KSU Housing”. 3. Campus visitors should use “KSU Guest”. What’s needed to connect to KSU Wireless? A computer with wireless network card A valid K-State eID/password How do I get help? Contact your departmental IT support staff or the K-State IT Help Desk (785-532-7722, helpdesk@k- state.edu). Windows XP configuration: KSU Wireless These instructions assume you are using the Windows management of the wireless network adapter. 1. Click the Start button in the bottom left corner of the desktop. (If you’re using the classic Windows start menu, click Settings.) Click Network Connections. Right-click Wireless Connections and select View Available Wireless Networks from the menu. OR: An alternative approach is to right-click the wireless networking icon in the bottom right corner of the Windows desktop. Select View Available Wireless Networks from the menu. 2. The Wireless Network Connection window will appear. 3. Click Change the order of preferred networks in the left-hand menu. The following window will appear. -

Cellular Wireless Networks

CHAPTER10 CELLULAR WIRELESS NETwORKS 10.1 Principles of Cellular Networks Cellular Network Organization Operation of Cellular Systems Mobile Radio Propagation Effects Fading in the Mobile Environment 10.2 Cellular Network Generations First Generation Second Generation Third Generation Fourth Generation 10.3 LTE-Advanced LTE-Advanced Architecture LTE-Advanced Transission Characteristics 10.4 Recommended Reading 10.5 Key Terms, Review Questions, and Problems 302 10.1 / PRINCIPLES OF CELLULAR NETWORKS 303 LEARNING OBJECTIVES After reading this chapter, you should be able to: ◆ Provide an overview of cellular network organization. ◆ Distinguish among four generations of mobile telephony. ◆ Understand the relative merits of time-division multiple access (TDMA) and code division multiple access (CDMA) approaches to mobile telephony. ◆ Present an overview of LTE-Advanced. Of all the tremendous advances in data communications and telecommunica- tions, perhaps the most revolutionary is the development of cellular networks. Cellular technology is the foundation of mobile wireless communications and supports users in locations that are not easily served by wired networks. Cellular technology is the underlying technology for mobile telephones, personal communications systems, wireless Internet and wireless Web appli- cations, and much more. We begin this chapter with a look at the basic principles used in all cellular networks. Then we look at specific cellular technologies and stan- dards, which are conveniently grouped into four generations. Finally, we examine LTE-Advanced, which is the standard for the fourth generation, in more detail. 10.1 PRINCIPLES OF CELLULAR NETWORKS Cellular radio is a technique that was developed to increase the capacity available for mobile radio telephone service. Prior to the introduction of cellular radio, mobile radio telephone service was only provided by a high-power transmitter/ receiver. -

A Survey on Mobile Wireless Networks Nirmal Lourdh Rayan, Chaitanya Krishna

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 5, Issue 1, January-2014 685 ISSN 2229-5518 A Survey on Mobile Wireless Networks Nirmal Lourdh Rayan, Chaitanya Krishna Abstract— Wireless communication is a transfer of data without using wired environment. The distance may be short (Television) or long (radio transmission). The term wireless will be used by cellular telephones, PDA’s etc. In this paper we will concentrate on the evolution of various generations of wireless network. Index Terms— Wireless, Radio Transmission, Mobile Network, Generations, Communication. —————————— —————————— 1 INTRODUCTION (TECHNOLOGY) er frequency of about 160MHz and up as it is transmitted be- tween radio antennas. The technique used for this is FDMA. In IRELESS telephone started with what you might call W terms of overall connection quality, 1G has low capacity, poor 0G if you can remember back that far. Just after the World War voice links, unreliable handoff, and no security since voice 2 mobile telephone service became available. In those days, calls were played back in radio antennas, making these calls you had a mobile operator to set up the calls and there were persuadable to unwanted monitoring by 3rd parties. First Gen- only a Few channels were available. 0G refers to radio tele- eration did maintain a few benefits over second generation. In phones that some had in cars before the advent of mobiles. comparison to 1G's AS (analog signals), 2G’s DS (digital sig- Mobile radio telephone systems preceded modern cellular nals) are very Similar on proximity and location. If a second mobile telephone technology. So they were the foregoer of the generation handset made a call far away from a cell tower, the first generation of cellular telephones, these systems are called DS (digital signal) may not be strong enough to reach the tow- 0G (zero generation) itself, and other basic ancillary data such er. -

Wireless Evolution •..••••.•.•...•....•.•..•.•••••••...••••••.•••.••••••.••.•.••.••••••• 4

Department of Justice ,"'''''''''<11 Bureau of Investigation ,Operational Technology Division WIRELESS EVDLUTIDN IN THIS Iselil-it:: .. WIRELESS EVOLUTIDN I!I TECH BYTES • LONG TERM EVOLUTIQN ill CLDUD SERVICES • 4G TECHNOLOGY ill GESTURE-RECOGNITION • FCC ON BROADBAND • ACTIVITY-BASED NAVIGATION 'aw PUIi! I' -. q f. 8tH'-.1 Waa 8RI,. (!.EIi/RiW81 R.d-nl)) - 11 - I! .el " Ij MESSAGE FROM MANAGEMENT b7E he bou~~aries of technology are constantly expanding. develop technical tools to combat threats along the Southwest Recognizing the pathway of emerging technology is Border. a key element to maintaining relevance in a rapidly changing technological environment. While this The customer-centric approach calls for a high degree of T collaboration among engineers, subject matter experts (SMEs), proficiency is fundamentally important in developing strategies that preserve long-term capabilities in the face of emerging and the investigator to determine needs and requirements. technologies, equally important is delivering technical solutions To encourage innovation, the technologists gain a better to meet the operational needs of the law enforcement understanding of the operational and investigative needs customer in a dynamic 'threat' environment. How can technical and tailor the technology to fit the end user's challenges. law enforcement organizations maintain the steady-state Rather than developing solutions from scratch, the customer production of tools and expertise for technical collection, while centric approach leverages and modifies the technoloe:v to infusing ideas and agility into our organizations to improve our fit the customer's nFlFlrt~.1 ability to deliver timely, relevant, and cutting edge tools to law enforcement customers? Balancing these two fundamentals through an effective business strategy is both a challenge and an opportunity for the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and other Federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies. -

Wireless Standards and Guidelines

Wireless Standards and Guidelines A Mandatory Reference for ADS Chapter 545 Full Revision Date: 02/11/2019 Responsible Office: M/CIO/IA File Name: 545mbg_021119 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 3 2. Purpose 3 3. Audience 3 4. Scope 3 4.1 Definitions 3 4.2 Individuals 4 4.3 Technologies, Networks, and Communications 4 4.4 Wireless Technology Locations 4 4.5 Classifications of Information 5 5. Exceptions 5 6. Wireless Spectrum Standard 5 6.1 Wireless Network Standards (Wi-Fi) 6 6.2 Access Agreements (Wi-Fi) 7 7. Security and Privacy 7 7.1 Cybersecurity 7 7.1.1 Implementation of Wi-Fi 7 7.1.2 Access and Usage Controls for Wi-Fi 8 7.1.3 Technology Controls for Other Wireless Technologies 9 7.2 Encryption 9 7.3 Continuous Monitoring 10 7.4 Installation of, Relocation of, or Changes to Wi-Fi 10 8. National Security Information Usage and Restrictions 11 8.1. Classified Systems and Workspaces 12 8.2. Sensitive Compartmented Information Facilities (SCIF) 12 9. List of Acronyms 13 2 1. Introduction Wireless networks, technologies, and communications must comply with the minimum specifications outlined in the provisions of federal policy, laws, and standards. The National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST) is responsible for developing information security standards and guidelines including minimum requirements for federal information systems. For wireless networks, technologies, and communications, the specific NIST Special Publications (SPs) that constitute the mandatory framework for implementation are SP 800-48, SP 800-97, and SP 800-153. NIST guidelines are consistent with the requirements of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Circular A-130, Managing Information as a Strategic Resource. -

Survey on Multi- Channel Access Methods for Wireless Lans

International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology (IJERT) ISSN: 2278-0181 Vol. 3 Issue 12, December-2014 Survey on Multi- Channel Access Methods for Wireless LANs Mahamat Habib Senoussi Hissein, Adrien Van Den Bossche, Thierry Val Université de Toulouse, UT2J, CNRS-IRIT IUT Blagnac, 1 place Georges Brassens BP60073, 31703 Blagnac, France Abstract— The last decade has seen great progress in the unpredictable nature of the network topology is essential field of wireless LANs. Their deployment is manifested in and complex. One of the major roles of an efficient access several areas of applications. However, these applications face method is to manage access to the medium, and therefore, many obstacles due to the complexity of managing the to solve the inherent problem of wireless hidden node medium access. This shortcoming usually leads to some where a transmitter node may not hear the transmission problems such as numerous collisions, throughput from another node that is not in its radio range. degradation and increased delays. To overcome these challenges, research works have focused on new multi- The multi-channel access methods allow different channel access methods that reduce contention as well as nodes to transmit simultaneously in the same coverage area collision probability. Several transmissions can occur on distinct frequency channels generally. This parallelism simultaneously in the same transmission area, thus increases the throughput and can potentially reduce the considerably improving throughput and reducing delays to transmission delay and contention. However, the use of access the medium. However, the idea of using multiple multiple channels does not go without problems. The channels arouses various problems such as the multi-channel majority of wireless communication interface is operating hidden terminal, deafness and the logical partition. -

Cellular Technology.Pdf

Cellular Technologies Mobile Device Investigations Program Technical Operations Division - DFB DHS - FLETC Basic Network Design Frequency Reuse and Planning 1. Cellular Technology enables mobile communication because they use of a complex two-way radio system between the mobile unit and the wireless network. 2. It uses radio frequencies (radio channels) over and over again throughout a market with minimal interference, to serve a large number of simultaneous conversations. 3. This concept is the central tenet to cellular design and is called frequency reuse. Basic Network Design Frequency Reuse and Planning 1. Repeatedly reusing radio frequencies over a geographical area. 2. Most frequency reuse plans are produced in groups of seven cells. Basic Network Design Note: Common frequencies are never contiguous 7 7 The U.S. Border Patrol uses a similar scheme with Mobile Radio Frequencies along the Southern border. By alternating frequencies between sectors, all USBP offices can communicate on just two frequencies Basic Network Design Frequency Reuse and Planning 1. There are numerous seven cell frequency reuse groups in each cellular carriers Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) or Rural Service Areas (RSA). 2. Higher traffic cells will receive more radio channels according to customer usage or subscriber density. Basic Network Design Frequency Reuse and Planning A frequency reuse plan is defined as how radio frequency (RF) engineers subdivide and assign the FCC allocated radio spectrum throughout the carriers market. Basic Network Design How Frequency Reuse Systems Work In concept frequency reuse maximizes coverage area and simultaneous conversation handling Cellular communication is made possible by the transmission of RF. This is achieved by the use of a powerful antenna broadcasting the signals. -

The AT&T Wireless Network

the AT&T wireless network the nation’s largest 4G network Faster In More Places With over 105 million wireless subscribers in service, AT&T is committed to creating the world’s most advanced mobile Internet experience. As a result of the more than $95 billion we’ve invested in our wireless and wireline networks over the past five years, we have led the mobile Internet revolution and today we deliver the nation’s largest 4G network. And now, with the launch of LTE, the AT&T network is faster in more places and expanding rapidly to bring speeds up to 10 times faster than 3G to more and more Americans*. And according to recent third-party speed tests by PCWorld, AT&T 4G LTE speeds are faster than the competition. Testing in 13 cities showed that AT&T’s combination of 4G LTE and HSPA+ technologies delivered faster download speeds, on average, than any other carrier tested**. More Broadband Access Options Built on the Global Standard for Mobile Devices Most AT&T smartphones automatically connect to our Wi-Fi hotspots, The AT&T wireless network is built on the GSM family of technologies, making access to the Internet while on the go even more convenient. the global technology standard upon which the vast majority of the Our Wi-Fi network is the nation’s largest***, with more than 31,000 AT&T world’s wireless services operate. With AT&T, you can make calls in over Wi-Fi hotspots domestically, plus access to nearly 341,000 hotspots 225 countries around the world and access data in over 205 countries. -

The Wireless Control Network: a New Approach for Control Over Networks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Real-Time and Embedded Systems Lab (mLAB) School of Engineering and Applied Science 2011 The Wireless Control Network: A New Approach for Control over Networks Miroslav Pajic University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Shreyas Sundaram University of Waterloo, [email protected] George Pappas University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Rahul Mangharam University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/mlab_papers Part of the Controls and Control Theory Commons, Electrical and Electronics Commons, and the Systems and Communications Commons Recommended Citation Miroslav Pajic, Shreyas Sundaram, George Pappas, and Rahul Mangharam, "The Wireless Control Network: A New Approach for Control over Networks", . January 2011. Suggested Citation: M. Pajic, S. Sundaram, G.J. Pappas and R. Mangharam, "The Wireless Control Network: A New Approach for Control over Networks", IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, vol. 56, no. 10, pp. 2305-2318, October 2011. ©2011 IEEE. Personal use of this material is permitted. However, permission to reprint/republish this material for advertising or promotional purposes or for creating new collective works for resale or redistribution to servers or lists, or to reuse any copyrighted component of this work in other works must be obtained from the IEEE. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/mlab_papers/29 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Wireless Control Network: A New Approach for Control over Networks Abstract We present a method to stabilize a plant with a network of resource constrained wireless nodes. As opposed to traditional networked control schemes where the nodes simply route information to and from a dedicated controller (perhaps performing some encoding along the way), our approach treats the network itself as the controller. -

Introduction to Wireless and Mobile Networks

© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning. ©NOT Jones FOR SALE & OR Bartlett DISTRIBUTION. Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALEPART OR DISTRIBUTION ONE © Rodolfo Clix/Dreamstime.com Introduction to Wireless © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOTand FOR SALEMobile OR DISTRIBUTION Networks © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTIONThe Evolution of Data NetworksNOT FOR 3SALE OR DISTRIBUTION The Evolution of Wired Networking to Wireless Networking 31 © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION The MobileNOT Revolution FOR SALE XX OR DISTRIBUTION Security Threats Overview— Wired, Wireless, and Mobile XX © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & -

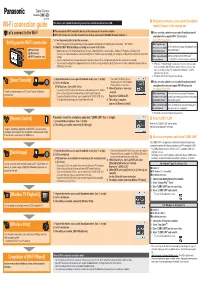

PDF Wi-Fi Connection Guide

Digital Camera Model No. DMC-SZ5 VQC9086 The camera is not capable of connecting to a wireless network via public wireless LAN. Register the wireless access point (broadband Wi-Fi connection guide router)/Connect to the smartphone You can connect Wi-Fi compatible devices to the camera over the wireless network. If you are using a wireless access point (broadband router)/ Let’s connect to the Wi-Fi *1 A PC, AV devices, etc. must be connected to a wireless access point (broadband router) in advance. smartphone that supports WPS (Push button) 1) Press the power button to turn the camera on. Select [WPS (Push-Button)] Setting up the Wi-Fi connection • The fi rst time you turn on the camera after purchase, setup items are displayed in the following order: Clock setting Wi-Fi Wizard. When registering a Set the wireless access point (broadband router) A 2) Make the [Wi-Fi Wizard] settings according to on-screen instructions. wireless access point Power button to the WPS mode.*2 • Make the settings in the following order: [Smart Transfer] [Remote Control] [Send Image] [Wireless TV Playback] [Wireless Print] (broadband router) [Wi-Fi] button • You can select whether to make the connection settings for each function. If you select [Skip], you can skip the settings and proceed to the next function’s B *2 Wi-Fi connection lamp settings. When connecting with Set the smartphone to the WPS mode. C • The Wi-Fi connection lamp blinks blue during sending/receiving data via Wi-Fi, and lights blue while the Wi-Fi connection is on standby.