Talk Is Cheap: Getting Serious About Preventing Child Soldiers P.W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beah, Ishmael 2007. the Making, and Unmaking, of a Child Soldier. New

Ishmael Beah - "A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier" - New York Times Page 1 of 16 January 14, 2007 The Making, and Unmaking, of a Child Soldier By ISHMAEL BEAH Sometimes I feel that living in New York City, having a good family and friends, and just being alive is a dream, that perhaps this second life of mine isn’t really happening. Whenever I speak at the United Nations, Unicef or elsewhere to raise awareness of the continual and rampant recruitment of children in wars around the world, I come to realize that I still do not fully understand how I could have possibly survived the civil war in my country, Sierra Leone. Most of my friends, after meeting the woman whom I think of as my new mother, a Brooklyn- born white Jewish-American, assume that I was either adopted at a very young age or that my mother married an African man. They would never imagine that I was 17 when I came to live with her and that I had been a child soldier and participated in one of the most brutal wars in recent history. In early 1993, when I was 12, I was separated from my family as the Sierra Leone civil war, which began two years earlier, came into my life. The rebel army, known as the Revolutionary United Front (R.U.F.), attacked my town in the southern part of the country. I ran away, along paths and roads that were littered with dead bodies, some mutilated in ways so horrible that looking at them left a permanent scar on my memory. -

The Phenomenon of Child Soldiers As Seen Through Ishmael Beah’S a Long Way Gone

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE, LITERATURE AND TRANSLATION STUDIES (IJELR) A QUARTERLY, INDEXED, REFEREED AND PEER REVIEWED OPEN ACCESS INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL http://www.ijelr.in (Impact Factor: 5.9745) (ICI) KY PUBLICATIONS RESEARCH ARTICLE ARTICLE Vol. 7. Issue.4. 2020 (Oct-Dec) THE PHENOMENON OF CHILD SOLDIERS AS SEEN THROUGH ISHMAEL BEAH’S A LONG WAY GONE SIDI CHABI Moussa Senior Lecturer of African Literature at the Department of Anglophone Studies Faculty of Letters, Arts and Human Sciences University of Parakou (UP), Parakou, Republic of BÉNIN Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT The present research work aims at examining critically the phenomenon of child soldiers as seen through Ishmael Beah’s A Long Way Gone. The issue of child soldiers is a worldwide phenomenon. However, it is more noticeable in developing nations where the lack of adequate social infrastructure and socio-economic programmes threatens the developmental needs of these children. Institutional assistance from governments, international institutions and Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) in providing some resources for the child soldiers is either inadequate or Article information Received:28/10/2020 non-existent. Hence the necessity to carry out this study to make visible and glaring Accepted: 22/12/2020 a situation that many people have consciously tried to ignore. The methodological Published online:27/12/2020 approaches used in this paper are the phenomenological and descriptive doi: 10.33329/ijelr.7.4.205 approaches. The literary theories applied to the study are psychological and psychoanalytic criticism. Psychological criticism deals with a literary work primarily as an expression, in fictional form, of the personality, state of mind, feelings, and desires of its author. -

Fall2011.Pdf

Grove Press Atlantic Monthly Press Black Cat The Mysterious Press Granta Fall 201 1 NOW AVAILABLE Complete and updated coverage by The New York Times about WikiLeaks and their controversial release of diplomatic cables and war logs OPEN SECRETS WikiLeaks, War, and American Diplomacy The New York Times Introduction by Bill Keller • Essential, unparalleled coverage A New York Times Best Seller from the expert writers at The New York Times on the hundreds he controversial antisecrecy organization WikiLeaks, led by Julian of thousands of confidential Assange, made headlines around the world when it released hundreds of documents revealed by WikiLeaks thousands of classified U.S. government documents in 2010. Allowed • Open Secrets also contains a T fascinating selection of original advance access, The New York Times sorted, searched, and analyzed these secret cables and war logs archives, placed them in context, and played a crucial role in breaking the WikiLeaks story. • online promotion at Open Secrets, originally published as an e-book, is the essential collection www.nytimes.com/opensecrets of the Times’s expert reporting and analysis, as well as the definitive chronicle of the documents’ release and the controversy that ensued. An introduction by Times executive editor, Bill Keller, details the paper’s cloak-and-dagger “We may look back at the war logs as relationship with a difficult source. Extended profiles of Assange and Bradley a herald of the end of America’s Manning, the Army private suspected of being his source, offer keen insight engagement in Afghanistan, just as into the main players. Collected news stories offer a broad and deep view into the Pentagon Papers are now a Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and the messy challenges facing American power milestone in our slo-mo exit from in Europe, Russia, Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. -

Child Soldiers and Blood Diamonds OVERVIEW & OBJECTIVES GRADES

Civil War in Sierra Leone: Child Soldiers and Blood Diamonds OVERVIEW & OBJECTIVES GRADES This lesson addresses the civil war in Sierra Leone to 8 illustrate the problem of child soldiers and the use of diamonds to finance the war. Students will draw TIME conclusions about the impact of the ten years civil war on the people of Sierra Leone, as well as on a boy who 4-5 class periods lived through it, by reading an excerpt from his book, A Long Way Gone. This lesson explores the concepts REQUIRED MATERIALS of civil war, conflict diamonds, and child soldiers in Sierra Leone while investigating countries of West Computer with projector Africa. Students will also examine the Rights of the Child and identify universal rights and Computer Internet access for students responsibilities. Pictures of child soldiers Poster paper and markers Students will be able to... Articles: Chapter One from A Long Way describe the effects of Sierra Leone’s civil war. Gone by Ishmael Beah; “What are Conflict analyze the connection between conflict Diamonds”; “How the Diamond Trade diamonds and child soldiers. Works”; “Rights for Every Child” analyze the role diamonds play in Africa’s civil wars Handouts: “Pre-Test on Sierra Leone”; compare their life in the United States with the “Post-Test on Sierra Leone”; “Sierra Leone lives of people in Sierra Leone. and Its Neighbors” describe the location and physical and human geography of Sierra Leone and West Africa. identify factors that affect Sierra Leone’s economic development analyze statistics to compare Sierra Leone and its neighbors. assess the Rights of the Child for Sierra Leone analyze the Rights of the Child and the responsibility to maintain the rights MINNESOTA SOCIAL STUDIES STANDARDS & BENCHMARKS Standard 1. -

Northumbria Research Link

Northumbria Research Link Citation: White, Dean (2012) The UK's Response to the Rwandan Genocide of 1994. Doctoral thesis, Northumbria University. This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/10122/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html THE UK’S RESPONSE TO THE RWANDAN GENOCIDE OF 1994 DEAN JAMES WHITE PhD 2012 THE UK’S RESPONSE TO THE RWANDAN GENOCIDE OF 1994 DEAN JAMES WHITE MA, BA (HONS) A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Northumbria at Newcastle for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Research undertaken in the School of Arts and Social Sciences. July 2012 ABSTRACT Former Prime Minister Tony Blair described the UK’s response to the Rwandan genocide as “We knew. -

New World Spring 2008.Pdf

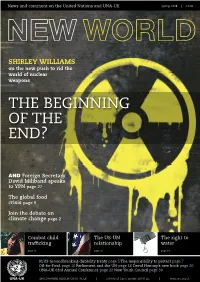

news and comment on the United nations and UnA-UK Spring 2008 | £3.00 NE W WORLD SHIRLEY WILLIAMS on the new push to rid the world of nuclear weapons The Beginning of The end? AND Foreign Secretary David Miliband speaks to YPN page 27 The global food crisis page 9 Join the debate on climate change page 2 Combat child The US-Un The right to trafficking relationship water page 16 page 10 page 14 PLUS groundbreaking disability treaty page 5 The responsibility to protect page 7 oil-for-food page 10 Parliament and the Un page 18 david hannay’s new book page 20 UnA-UK 63rd Annual Conference page 22 new Youth Council page 30 UNA-UK UNITED NATIONS ASSOCIATION OF THE UK | 3 Whitehall Court, London SW1A 2EL | www.una.org.uk UNA-UK What is the role of the United Nations in finding solutions to climate change and building CLIMATE CHANGE resilience to its impacts? CONFERENCE SERIES Is the UK government doing enough to build 2008-09 a low-carbon economy? What can you do as an individual ? An upcoming series of one-day conferences on climate change, to be held by UNA-UK in 2008-2009 in different cities around the UK, will be tackling these questions. The first conference of the series will be held in Birmingham on Saturday, 7 June 2008. The second will be held in Belfast on Thursday, 6 November 2008. Two further events are being planned for the autumn of 2008 and early 2009 – one in Wales and the other in Scotland. -

Ishmael Beah

Ishmael Beah Ishmael Beah was born in Sierra Leone. He is the "New York Times" bestselling author of "A Long Way Gone, Memoirs of a Boy Soldier". His work has appeared in the "New York Times Magazine", "Vespertine Press", "LIT" and "Parabola" magazines. He is a UNICEF advocate for Children Affected by War and a member of the Human Rights Watch Children’s Advisory Committee. He is a graduate of Oberlin College, Ohio with a B.A in Political Science. FLYING WITH ONE WING By Ishmael Beah It was the first time she had seen her father weep. His body trembled as he walked onto a piece of land that was now consumed by grass. A tall cement pillar still stood on the far end of the land, bearing residues of smoke, rain, dust, and scars from sharp metals that had left visible holes of dark moments. He looked back at his daughter and managed to conjure a smile. He kicked in the grass to reveal some part of the remaining foundation. “This is where I use to sit, this was my classroom.” He placed his fingers on the ground. “This was my school. I can still hear our voices reciting the alphabet, greeting our teacher, ‘good morning Mr. Kanagbole.’ and running outside during break, screaming our desired positions for the football match that we played everyday.” He continued and sat on the ground. His daughter sat next to him. She was accompanying her father back to his home where he had always said the core of his heart still lived. -

Lead IG for Overseas Contingency Operations

LEAD INSPECTOR GENERAL FOR OVERSEAS CONTINGENCY OPERATIONS OPERATION INHERENT RESOLVE REPORT TO THE UNITED STATES CONGRESS OCTOBER 1, 2016‒DECEMBER 31, 2016 LEAD INSPECTOR GENERAL MISSION The Lead Inspector General for Overseas Contingency Operations will coordinate among the Inspectors General specified under the law to: • develop a joint strategic plan to conduct comprehensive oversight over all aspects of the contingency operation • ensure independent and effective oversight of all programs and operations of the federal government in support of the contingency operation through either joint or individual audits, inspections, and investigations • promote economy, efficiency, and effectiveness and prevent, detect, and deter fraud, waste, and abuse • perform analyses to ascertain the accuracy of information provided by federal agencies relating to obligations and expenditures, costs of programs and projects, accountability of funds, and the award and execution of major contracts, grants, and agreements • report quarterly and biannually to the Congress and the public on the contingency operation and activities of the Lead Inspector General (Pursuant to sections 2, 4, and 8L of the Inspector General Act of 1978) FOREWORD We are pleased to publish the Lead Inspector General (Lead IG) quarterly report on Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR). This is our eighth quarterly report on the overseas contingency operation (OCO), discharging our individual and collective agency oversight responsibilities pursuant to sections 2, 4, and 8L of the Inspector General Act of 1978. OIR is dedicated to countering the terrorist threat posed by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) in Iraq, Syria, the region, and the broader international community. The U.S. -

The Kosovo Report

THE KOSOVO REPORT CONFLICT v INTERNATIONAL RESPONSE v LESSONS LEARNED v THE INDEPENDENT INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION ON KOSOVO 1 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford Executive Summary • 1 It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, Address by former President Nelson Mandela • 14 and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Map of Kosovo • 18 Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Introduction • 19 Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paulo Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw PART I: WHAT HAPPENED? with associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Preface • 29 Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the uk and in certain other countries 1. The Origins of the Kosovo Crisis • 33 Published in the United States 2. Internal Armed Conflict: February 1998–March 1999 •67 by Oxford University Press Inc., New York 3. International War Supervenes: March 1999–June 1999 • 85 © Oxford University Press 2000 4. Kosovo under United Nations Rule • 99 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) PART II: ANALYSIS First published 2000 5. The Diplomatic Dimension • 131 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, 6. International Law and Humanitarian Intervention • 163 without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, 7. Humanitarian Organizations and the Role of Media • 201 or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organisation. -

Papers from the Conference on Homeland Protection

“. to insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence . .” PAPERS FROM THE CONFERENCE ON HOMELAND PROTECTION Edited by Max G. Manwaring October 2000 ***** The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. This report is cleared for public release; distribution is unlimited. ***** Comments pertaining to this report are invited and should be forwarded to: Director, Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 122 Forbes Ave., Carlisle, PA 17013-5244. Copies of this report may be obtained from the Publications and Production Office by calling commercial (717) 245-4133, FAX (717) 245-3820, or via the Internet at [email protected] ***** Most 1993, 1994, and all later Strategic Studies Institute (SSI) monographs are available on the SSI Homepage for electronic dissemination. SSI’s Homepage address is: http://carlisle-www.army. mil/usassi/welcome.htm ***** The Strategic Studies Institute publishes a monthly e-mail newsletter to update the national security community on the research of our analysts, recent and forthcoming publications, and upcoming conferences sponsored by the Institute. Each newsletter also provides a strategic commentary by one of our research analysts. If you are interested in receiving this newsletter, please let us know by e-mail at [email protected] or by calling (717) 245-3133. ISBN 1-58487-036-2 ii CONTENTS Foreword ........................ v Overview Max G. Manwaring ............... 1 1. A Strategic Perspective on U. S. Homeland Defense: Problem and Response John J. -

Media Reporting of War Crimes Trials and Civil Society Responses in Post-Conflict Sierra Leone

Media Reporting of War Crimes Trials and Civil Society Responses in Post-Conflict Sierra Leone Abou Binneh-Kamara This is a digitised version of a dissertation submitted to the University of Bedfordshire. It is available to view only. This item is subject to copyright. Media Reporting of War Crimes Trials and Civil Society Responses in Post-Conflict Sierra Leone By Abou Bhakarr M. Binneh-Kamara A thesis submitted to the University of Bedfordshire in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. January, 2015 ABSTRACT This study, which seeks to contribute to the shared-body of knowledge on media and war crimes jurisprudence, gauges the impact of the media’s coverage of the Civil Defence Forces (CDF) and Charles Taylor trials conducted by the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL) on the functionality of civil society organizations (CSOs) in promoting transitional (post-conflict) justice and democratic legitimacy in Sierra Leone. The media’s impact is gauged by contextualizing the stimulus-response paradigm in the behavioral sciences. Thus, media contents are rationalized as stimuli and the perceptions of CSOs’ representatives on the media’s coverage of the trials are deemed to be their responses. The study adopts contents (framing) and discourse analyses and semi-structured interviews to analyse the publications of the selected media (For Di People, Standard Times and Awoko) in Sierra Leone. The responses to such contents are theoretically explained with the aid of the structured interpretative and post-modernistic response approaches to media contents. And, methodologically, CSOs’ representatives’ responses to the media’s contents are elicited by ethnographic surveys (group discussions) conducted across the country. -

War Reporting in the International Press: a Critical Discourse Analysis of the Gaza War of 2008-2009

War Reporting in the International Press: A Critical Discourse Analysis of the Gaza War of 2008-2009 Dissertation Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Hamburg zur Erlangung des Grades des Doktors der Philosophie an der Fakultät für Geisteswissenschaften der Universität Hamburg Mohammedwesam Amer Hamburg, June 2015 War Reporting in the International Press: A Critical Discourse Analysis of the Gaza War of 2008-2009 Evaluators 1. Prof. Dr. Jannis Androutsopoulos 2. Prof. Dr. Irene Neverla 3. Prof. Dr. Kathrin Fahlenbrach Date of Oral Defence: 30.10.2015 Declaration • I hereby declare and certify that I am the author of this study which is submitted to the University of Hamburg in fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. • This is my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. • This original work or part of it has not been submitted to any other institution or university for a degree. Mohammedwesam Amer June 2015 I Abstract This study analyses the representation of social actors in reports on the Gaza war of 2008-09 in four international newspapers: The Guardian , The Times London , The New York Times and The Washington Post . The study draws on three analytical frameworks from the area of Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) models: the transitivity model by Halliday (1985/1994), the socio- semantic inventory by Van Leeuwen (1996), and the classification of quotation patterns by Richardson (2007). The sample of this study consists of all headlines (146) of the relevant news stories and a non-random sample of (40) news stories and (7) editorials.