The Lost Correspondence of Francis Crick Alexander Gann and Jan Witkowski Unveil Newly Found Letters Between Key Players in the DNA Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 in the Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU)

THE UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER FACTS AND FIGURES 2020 2 The University 4 World ranking 6 Academic pedigree 8 World-class research CONTENTS 10 Students 12 Making a difference 14 Global challenges, Manchester solutions 16 Stellify 18 Graduate careers 20 Staff 22 Faculties and Schools 24 Alumni 26 Innovation 28 Widening participation UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER 30 Cultural institutions UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER 32 Income 34 Campus investment 36 At a glance 1 THE UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER Our vision is to be recognised globally for the excellence of our people, research, learning and innovation, and for the benefits we bring to society and the environment. Our core goals and strategic themes Research and discovery Teaching and learning Social responsibility Our people, our values Innovation Civic engagement Global influence 2 3 WORLD RANKING The quality of our teaching and the impact of our research are the cornerstones of our success. We have risen from 78th in 2004* to 33rd – our highest ever place – in 2019 in the Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU). League table World ranking European ranking UK ranking 33 8 6 ARWU 33 8 6 WORLD EUROPE UK QS 27 8 6 Times Higher Education 55 16 8 *2004 ranking refers to the Victoria University of Manchester prior to the merger with UMIST. 4 5 ACADEMIC PEDIGREE 1906 1908 1915 1922 1922 We attract the highest-calibre researchers and teachers, with 25 Nobel Prize winners among J Thomson Ernest Rutherford William Archibald V Hill Niels Bohr Physics Chemistry Larence Bragg Physiology or Medicine Physics our current and former staff and students. -

Biochemistrystanford00kornrich.Pdf

University of California Berkeley Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Program in the History of the Biosciences and Biotechnology Arthur Kornberg, M.D. BIOCHEMISTRY AT STANFORD, BIOTECHNOLOGY AT DNAX With an Introduction by Joshua Lederberg Interviews Conducted by Sally Smith Hughes, Ph.D. in 1997 Copyright 1998 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the Nation. Oral history is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well- informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Arthur Kornberg, M.D., dated June 18, 1997. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize Winners Part 2 - 1951 to 1974: from Crick and Watson to Dorothy Hodgkin

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize winners part 2 - 1951 to 1974: from Crick and Watson to Dorothy Hodgkin By Cambridge News | Posted: January 18, 2016 By Adam Care The News has been rounding up all of Cambridge's 92 Nobel Laureates, celebrating over 100 years of scientific and social innovation. ADVERTISING In this installment we move from 1951 to 1974, a period which saw a host of dramatic breakthroughs, in biology, atomic science, the discovery of pulsars and theories of global trade. It's also a period which saw The Eagle pub come to national prominence and the appearance of the first female name in Cambridge University's long Nobel history. The Gender Pay Gap Sale! Shop Online to get 13.9% off From 8 - 11 March, get 13.9% off 1,000s of items, it highlights the pay gap between men & women in the UK. Shop the Gender Pay Gap Sale – now. Promoted by Oxfam 1. 1951 Ernest Walton, Trinity College: Nobel Prize in Physics, for using accelerated particles to study atomic nuclei 2. 1951 John Cockcroft, St John's / Churchill Colleges: Nobel Prize in Physics, for using accelerated particles to study atomic nuclei Walton and Cockcroft shared the 1951 physics prize after they famously 'split the atom' in Cambridge 1932, ushering in the nuclear age with their particle accelerator, the Cockcroft-Walton generator. In later years Walton returned to his native Ireland, as a fellow of Trinity College Dublin, while in 1951 Cockcroft became the first master of Churchill College, where he died 16 years later. 3. 1952 Archer Martin, Peterhouse: Nobel Prize in Chemistry, for developing partition chromatography 4. -

A Singing, Dancing Universe Jon Butterworth Enjoys a Celebration of Mathematics-Led Theoretical Physics

SPRING BOOKS COMMENT under physicist and Nobel laureate William to the intensely scrutinized narrative on the discovery “may turn out to be the greatest Henry Bragg, studying small mol ecules such double helix itself, he clarifies key issues. He development in the field of molecular genet- as tartaric acid. Moving to the University points out that the infamous conflict between ics in recent years”. And, on occasion, the of Leeds, UK, in 1928, Astbury probed the Wilkins and chemist Rosalind Franklin arose scope is too broad. The tragic figure of Nikolai structure of biological fibres such as hair. His from actions of John Randall, head of the Vavilov, the great Soviet plant geneticist of the colleague Florence Bell took the first X-ray biophysics unit at King’s College London. He early twentieth century who perished in the diffraction photographs of DNA, leading to implied to Franklin that she would take over Gulag, features prominently, but I am not sure the “pile of pennies” model (W. T. Astbury Wilkins’ work on DNA, yet gave Wilkins the how relevant his research is here. Yet pulling and F. O. Bell Nature 141, 747–748; 1938). impression she would be his assistant. Wilkins such figures into the limelight is partly what Her photos, plagued by technical limitations, conceded the DNA work to Franklin, and distinguishes Williams’s book from others. were fuzzy. But in 1951, Astbury’s lab pro- PhD student Raymond Gosling became her What of those others? Franklin Portugal duced a gem, by the rarely mentioned Elwyn assistant. It was Gosling who, under Franklin’s and Jack Cohen covered much the same Beighton. -

2004 Albert Lasker Nomination Form

albert and mary lasker foundation 110 East 42nd Street Suite 1300 New York, ny 10017 November 3, 2003 tel 212 286-0222 fax 212 286-0924 Greetings: www.laskerfoundation.org james w. fordyce On behalf of the Albert and Mary Lasker Foundation, I invite you to submit a nomination Chairman neen hunt, ed.d. for the 2004 Albert Lasker Medical Research Awards. President mrs. anne b. fordyce The Awards will be offered in three categories: Basic Medical Research, Clinical Medical Vice President Research, and Special Achievement in Medical Science. This is the 59th year of these christopher w. brody Treasurer awards. Since the program was first established in 1944, 68 Lasker Laureates have later w. michael brown Secretary won Nobel Prizes. Additional information on previous Lasker Laureates can be found jordan u. gutterman, m.d. online at our web site http://www.laskerfoundation.org. Representative Albert Lasker Medical Research Awards Program Nominations that have been made in previous years may be updated and resubmitted in purnell w. choppin, m.d. accordance with the instructions on page 2 of this nomination booklet. daniel e. koshland, jr., ph.d. mrs. william mccormick blair, jr. the honorable mark o. hatfied Nominations should be received by the Foundation no later than February 2, 2004. Directors Emeritus A distinguished panel of jurors will select the scientists to be honored. The 2004 Albert Lasker Medical Research Awards will be presented at a luncheon ceremony given by the Foundation in New York City on Friday, October 1, 2004. Sincerely, Joseph L. Goldstein, M.D. Chairman, Awards Jury Albert Lasker Medical Research Awards ALBERT LASKER MEDICAL2004 RESEARCH AWARDS PURPOSE AND DESCRIPTION OF THE AWARDS The major purpose of these Awards is to recognize and honor individuals who have made signifi- cant contributions in basic or clinical research in diseases that are the main cause of death and disability. -

Physics Today - February 2003

Physics Today - February 2003 Rosalind Franklin and the Double Helix Although she made essential contributions toward elucidating the structure of DNA, Rosalind Franklin is known to many only as seen through the distorting lens of James Watson's book, The Double Helix. by Lynne Osman Elkin - California State University, Hayward In 1962, James Watson, then at Harvard University, and Cambridge University's Francis Crick stood next to Maurice Wilkins from King's College, London, to receive the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their "discoveries concerning the molecular structure of nucleic acids and its significance for information transfer in living material." Watson and Crick could not have proposed their celebrated structure for DNA as early in 1953 as they did without access to experimental results obtained by King's College scientist Rosalind Franklin. Franklin had died of cancer in 1958 at age 37, and so was ineligible to share the honor. Her conspicuous absence from the awards ceremony--the dramatic culmination of the struggle to determine the structure of DNA--probably contributed to the neglect, for several decades, of Franklin's role in the DNA story. She most likely never knew how significantly her data influenced Watson and Crick's proposal. Franklin was born 25 July 1920 to Muriel Waley Franklin and merchant banker Ellis Franklin, both members of educated and socially conscious Jewish families. They were a close immediate family, prone to lively discussion and vigorous debates at which the politically liberal, logical, and determined Rosalind excelled: She would even argue with her assertive, conservative father. Early in life, Rosalind manifested the creativity and drive characteristic of the Franklin women, and some of the Waley women, who were expected to focus their education, talents, and skills on political, educational, and charitable forms of community service. -

Watson's Way with Words

books and arts My teeth were set on edge by reference to “the stable form of uranium”,a violation of Kepler’s second law in a description of how the Earth’s orbit would change under various circumstances, and by “the rest mass of the neutrino is 4 eV”. Collins has been well served by his editor and publisher, but not perfectly. There are un-sort-out-able mismatches between text and index, references and figures; acronyms D.WRITING LIFE OF JAMES THE WATSON in the second half of the alphabet go un- decoded; several well-known names are misspelled. And readers are informed that Weber’s death occurred “on September 31, E. C. FRIEDBERG, 2000”. Well, Joe always said he could do things that other people couldn’t, but there are limits. Incidentally, my adviser was partly right: I should not have agreed to review this book. It is very much harder to hear harsh, some- times false, things said about one’s spouse after he can no longer defend himself. I am not alone in this feeling. Carvel Gold, widow of Thomas Gold, whose work was also far from universally accepted (see Nature 430, 415;2004),says the same thing. ■ Virginia Trimble is at the University of California, Irvine, California 92697-4575, USA. She and Joe The write idea? In The Double Helix,James Watson gave Weber were married from 16 March 1972 until his a personal account of the quest for the structure of DNA. death on 30 September 2000. Watson set out to produce a good story that the public would enjoy as much as The Great Gatsby.He started writing in 1962 with the working title “Honest Jim”,which is illumi- Watson’s way nating in itself. -

Moore Noller

2002 Ada Doisy Lectures Ada Doisy Lecturers 2003 in BIOCHEMISTRY Sponsored by the Department of Biochemistry • University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Dr. Peter B. 1970-71 Charles Huggins* and Elwood V. Jensen A76 1972-73 Paul Berg* and Walter Gilbert* Moore 1973-74 Saul Roseman and Bruce Ames Department of Molecular carbonyl Biophysics & Biochemistry Phe 1974-75 Arthur Kornberg* and Osamu Hayaishi Yale University C75 1976-77 Luis F. Leloir* New Haven, Connecticutt 1977-78 Albert L. Lehninger and Efraim Racker 2' OH attacking 1978-79 Donald D. Brown and Herbert Boyer amino N3 Tyr 1979-80 Charles Yanofsky A76 4:00 p.m. A2486 1980-81 Leroy E. Hood Thursday, May 1, 2003 (2491) 1983-84 Joseph L. Goldstein* and Michael S. Brown* Medical Sciences Auditorium 1984-85 Joan Steitz and Phillip Sharp* Structure and Function in 1985-86 Stephen J. Benkovic and Jeremy R. Knowles the Large Ribosomal Subunit 1986-87 Tom Maniatis and Mark Ptashne 1988-89 J. Michael Bishop* and Harold E. Varmus* 1989-90 Kurt Wüthrich Dr. Harry F. 1990-91 Edmond H. Fischer* and Edwin G. Krebs* 1993-94 Bert W. O’Malley Noller 1994-95 Earl W. Davie and John W. Suttie Director, Center for Molecular Biology of RNA 1995-96 Richard J. Roberts* University of California, Santa Cruz 1996-97 Ronald M. Evans Santa Cruz, California 1998-99 Elizabeth H. Blackburn 1999-2000 Carl R. Woese and Norman R. Pace 2000-01 Willem P. C. Stemmer and Ronald W. Davis 2001-02 Janos K. Lanyi and Sir John E. Walker* 12:00 noon 2002-03 Peter B. -

Fire Departments of Pathology and Genetics, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Room L235, Stanford, CA 94305-5324, USA

GENE SILENCING BY DOUBLE STRANDED RNA Nobel Lecture, December 8, 2006 by Andrew Z. Fire Departments of Pathology and Genetics, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Room L235, Stanford, CA 94305-5324, USA. I would like to thank the Nobel Assembly of the Karolinska Institutet for the opportunity to describe some recent work on RNA-triggered gene silencing. First a few disclaimers, however. Telling the full story of gene silencing would be a mammoth enterprise that would take me many years to write and would take you well into the night to read. So we’ll need to abbreviate the story more than a little. Second (and as you will see) we are only in the dawn of our knowledge; so consider the following to be primer... the best we could do as of December 8th, 2006. And third, please understand that the story that I am telling represents the work of several generations of biologists, chemists, and many shades in between. I’m pleased and proud that work from my labo- ratory has contributed to the field, and that this has led to my being chosen as one of the messengers to relay the story in this forum. At the same time, I hope that there will be no confusion of equating our modest contributions with those of the much grander RNAi enterprise. DOUBLE STRANDED RNA AS A BIOLOGICAL ALARM SIGNAL These disclaimers in hand, the story can now start with a biography of the first main character. Double stranded RNA is probably as old (or almost as old) as life on earth. -

William Lawrence Bragg

W ILLIAM L AWRENCE B R A G G The diffraction of X-rays by crystals Nobel Lecture, September 6, 1922* It is with the very greatest pleasure that I take this opportunity of expressing my gratitude to you for the great honour which you bestowed upon me, when you awarded my father and myself the Nobel Prize for Physics in the year 1915. In other years scientists have come here to express their thanks to you, who have received this great distinction for the work of an illustrious career devoted to research. That you should have given me, at the very out- set of my scientific career, even the most humble place amongst their ranks, is an honour of which I cannot but be very proud. You invited me here two years ago, after the end of the war, but a series of unfortunate circumstances made it impossible for me to accept your invi- tation. I have always profoundly regretted this, and it was therefore with the very greatest satisfaction that I received the invitation of Prof. Arrhenius a few months ago, and arranged for this visit. I am at last able to tell you how deeply grateful I am to you, and to give you my thanks in person. You have already honoured with the Nobel Prize Prof. von Laue, to whom we owe the great discovery which has made possible all progress in a new realm of science, the study of the structure of matter by the diffraction of X-rays. Prof von Laue, in his Nobel Lecture, has described to you how he was led to make his epochal discovery. -

MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo

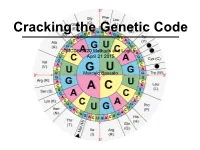

Cracking the Genetic Code MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) Frederick Griffith The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) Oswald Avery Alfred Hershey Martha Chase The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) Linus Carl Pauling The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) James Watson and Francis Crick The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) How is DNA (4 nucleotides) the genetic material while proteins (20 amino acids) are the building blocks? ? DNA Protein ? The Coding Craze ? DNA Protein What was already known? • DNA resides inside the nucleus - DNA is not the carrier • Protein synthesis occur in the cytoplasm through ribosomes {• Only RNA is associated with ribosomes (no DNA) - rRNA is not the carrier { • Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) was a homogeneous population The “messenger RNA” hypothesis François Jacob Jacques Monod The Coding Craze ? DNA RNA Protein RNA Tie Club Table from Wikipedia The Coding Craze Who won the race Marshall Nirenberg J. -

A Brief History of Microwave Engineering

A BRIEF HISTORY OF MICROWAVE ENGINEERING S.N. SINHA PROFESSOR DEPT. OF ELECTRONICS & COMPUTER ENGINEERING IIT ROORKEE Multiple Name Symbol Multiple Name Symbol 100 hertz Hz 101 decahertz daHz 10–1 decihertz dHz 102 hectohertz hHz 10–2 centihertz cHz 103 kilohertz kHz 10–3 millihertz mHz 106 megahertz MHz 10–6 microhertz µHz 109 gigahertz GHz 10–9 nanohertz nHz 1012 terahertz THz 10–12 picohertz pHz 1015 petahertz PHz 10–15 femtohertz fHz 1018 exahertz EHz 10–18 attohertz aHz 1021 zettahertz ZHz 10–21 zeptohertz zHz 1024 yottahertz YHz 10–24 yoctohertz yHz • John Napier, born in 1550 • Developed the theory of John Napier logarithms, in order to eliminate the frustration of hand calculations of division, multiplication, squares, etc. • We use logarithms every day in microwaves when we refer to the decibel • The Neper, a unitless quantity for dealing with ratios, is named after John Napier Laurent Cassegrain • Not much is known about Laurent Cassegrain, a Catholic Priest in Chartre, France, who in 1672 reportedly submitted a manuscript on a new type of reflecting telescope that bears his name. • The Cassegrain antenna is an an adaptation of the telescope • Hans Christian Oersted, one of the leading scientists of the Hans Christian Oersted nineteenth century, played a crucial role in understanding electromagnetism • He showed that electricity and magnetism were related phenomena, a finding that laid the foundation for the theory of electromagnetism and for the research that later created such technologies as radio, television and fiber optics • The unit of magnetic field strength was named the Oersted in his honor.