A Short Journey from England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Caernarfonshire Eagles: Development of a Traditional Emblem and County Flag

The Association of British Counties The Caernarfonshire Eagles: Development of a Traditional Emblem and County Flag by Philip S. Tibbetts & Jason Saber - 2 - Contents Essay.......................................................................................................................................................3 Appendix: Timeline..............................................................................................................................16 Bibliography Books.......................................................................................................................................17 Internet....................................................................................................................................18 List of Illustrations Maredudd ap Ieuan ap Robert Memorial..............................................................................................4 Wynn of Gwydir Monument.................................................................................................................4 Blayney Room Carving...........................................................................................................................5 Scott-Giles Illustration of Caernarfonshire Device.................................................................................8 Cigarette Card Illustration of Caernarvon Device..................................................................................8 Caernarfonshire Police Constabulary Helmet Plate...............................................................................9 -

John Archibald Goodall, F.S.A

Third Series Vol. II part 1. ISSN 0010-003X No. 211 Price £12.00 Spring 2006 THE COAT OF ARMS an heraldic journal published twice yearly by The Heraldry Society THE COAT OF ARMS The journal of the Heraldry Society Third series Volume II 2006 Part 1 Number 211 in the original series started in 1952 The Coat of Arms is published twice a year by The Heraldry Society, whose registered office is 53 High Street, Burnham, Slough SL1 7JX. The Society was registered in England in 1956 as registered charity no. 241456. Founding Editor † John Brooke-Little, C.V.O., M.A., F.H.S. Honorary Editors C. E. A. Cheesman, M.A., PH.D., Rouge Dragon Pursuivant M. P. D. O'Donoghue, M.A., Bluemantle Pursuivant Editorial Committee Adrian Ailes, B.A., F.S.A., F.H.S. Andrew Hanham, B.A., PH.D Advertizing Manager John Tunesi of Liongam PLATE 3 . F.S.A , Goodall . A . A n Joh : Photo JOHN GOODALL (1930-2005) Photographed in the library of the Society of Antiquaries with a copy of the Parliamentary Roll (ed. N.H. Nicolas, 1829). JOHN ARCHIBALD GOODALL, F.S.A. (1930-2005) John Goodall, a member of the editorial committee of this journal, and once a fre• quent contributor to its pages, died in St Thomas' Hospital of an infection on 23 November 2005. He was suffering from cancer. His prodigiously wide learning spread back to the Byzantine and ancient worlds, and as far afield as China and Japan, but particularly focused on medieval rolls of arms, on memorial brasses and on European heraldry. -

F. I a Short List of Contents in an Early Nineteenth-Century Hand, Together with Notes in Pencil in Another Contemporary Or Later Hand

f. i A short list of contents in an early nineteenth-century hand, together with notes in pencil in another contemporary or later hand. p. 1 [Englynion] (a) Or llydy daythom er llediaith ... Richard Dauid Esgob Dewi Pan fy Owen Glyndwr 1400 (b) Mil a ffedwarcant heb ddim mwy ... Pan fy mas Banberi 1469 (c) Mil oedd oed Iessy molaf ... Terwin a Twrnei 1513 (d) Tair ar ddeg gwaneg gogoniant ... Bwlen a Mwtrel 1544 (e) Pymtheckant gwarant gwir ... pp. 7-18 Hughe Mortymer y kynta a ddoeth i Loeger geda william Bastard a hwnn a briodes Matilda verch Willm ap Ballo ag iddvnt i bv fab a hwnnw a elwid Roger Mortimer ... Mam Kaswallon Lawhir oedd Brawst vz Tythlyn Prydein. Includes the pedigrees of 'Harri wythfed brenin Lloeger ap Hari seithved brenin Lloeger ap Edmwnd Iarll Ridssmwnt ap owain ap Mred ap Tvdvr' to 'Kadwaladr Fendigaid brenin y Brytaniaid' (pp. 8-9); and ‘[M]ared mam Owain ap Mred ap Tvdvr' to 'Beli Mawr ap Mynogan’ (pp. 10-11). pp. 18-22 Plant Griffith ap Kynan ap Iago oedd Owain Gwynedd, Kydwaladr, Kydwallo a Mareda ... a Gwladis vz Gr: gwraig Rys Ifangke ap Rys Mychell, i mam oedd Ranwlld vz Reinallt brenin Manawe. pp. 22-3 Plant Rodri Mawr Anarawd Cadell Rodri Vychan Meirig Mervin Tvdwal Gwriad a Gwyddlid ... Eithir kynta dyn addyg dy dalaith i ar Ryeni brochwel Ysherog fv Bleddyn ap Kynfyn. p. 24 Engharad vz Owain ap Edwin frenin Tegangl gwraig Gr: ap Kynan oedd honno a grono ap Owain ap Edwin brawd a chwaer ... Gr: Maelor ap Sussanna ag Yngharad vz Owain Gwynedd oedd yn Gefnder a chyfn[i]ther ag am vod Gr: Maelor yn briod ai gyfnither i gwnaeth Madog ap Gr: Maelor Mynachlog lan Egwest dros enaid i dad. -

Welshpool Town & Community Plan

WELSHPOOL TOWN COUNCIL WELSHPOOL TOWN & COMMUNITY PLAN 2017 – 2022 WELSHPOOL TOWN COUNCIL Triangle House Union Street Welshpool SY21 7PG Tel 01938 553142 Email [email protected] 25th October 2017 ADOPTED PLAN 1 | P a g e WELSHPOOL TOWN COUNCIL CONTENTS No Heading Page 1 Introduction and Background 3-4 2 Local Development Plan 5 3 Welshpool and its Economic Base 6-7 4 Consultation method 8 5 The Town Plan Policy elements 9 6 Action plan 10 7 Review and monitoring 11 8 Relevant documents and plans 12 9 Signatures and Adoption 13 Appendix A Town boundaries 14 B Census for Welshpool 15-17 C Consultation results 18-39 D Town plan policy elements 40 D1 Town Centre Policy 40 D2 Shopping Policy 40-42 D3 Residential Policy 42 D4 Industrial and Commercial Policy 42 D5 Out of Town Shopping 43 D6 Markets 43 D7 Main Line Rail Policy 43 D8 National and local bus policy 44-46 D9 Taxi provision 46 D10 Community Transport 46 D11 Car parking policy 46 D12 Tourist Information Policy 47 D13 Airport 47 D14 Montgomery Canal 47-48 D15 Road and Traffic Policy 48 D16 Town Centre Facilities Policy 49 D17 Other Town Centre Policies 49-50 D18 Pool Quay 50 D19 The Belan 50 D20 Flood Plains 50 D21 Renewable Energy 51 D22 Other specific policies 51-53 D23 Access for All Policy 53 D24 Policies for the young 53 D25 Language Policy 54 E One Way System review actions 55-56 F 2015 Town Plan actions and results 57-65 G Overall Plans showing land uses (LDP adjusted) 66-71 H Town Centre Planning detail 72 J Town Centre Car parking plan 73 K Priority Order for projects in the plan 74 2 | P a g e WELSHPOOL TOWN COUNCIL 1 Introduction and background 1.1 Welshpool Town Council first published a Town Plan in 2008, Community Plans in 2007, 2010 and 2014, Transport Plan in 2014 and Regeneration Plan in 2013 all of which has guided the decisions made by the Council during the period from then to 2015. -

Arfau'r Beirdd 1

Pennod 1: Cyflwyniad 1.1 Arfau a‘r Bardd Yn y gynharaf o‘r llawysgrifau sy‘n cynnwys y Gramadegau barddol a briodolir i Einion Offeiriad a Dafydd Ddu, sef llsgr. Peniarth 20, dywedir y dylid moli arglwydd o’y gedernyt, a’y dewred, a’y vilwryaeth. Daw hyn ar frig rhestr o nodweddion eraill, gan gyfeirio hefyd at allu ar wyr a meirch ac arueu, ac adurnyant gwisgoed ac arueu a thlysseu.1 Er bod y ‗Gramadegau‘ wedi eu hysgrifennu rai degawdau ar ôl y cerddi diweddarach a ystyrir yn yr astudiaeth hon, adlewyrchant yn deg bwysigrwyddd arfau fel rhan o ‗arfogaeth‘ lenyddol y beirdd drwy‘r Oesoedd Canol: caiff arfau eu defnyddio wrth foli gwrhydri a milwriaeth, ac fel rhan o ddarlun arwrol o wrthrych cerdd a awgrymai harddwch personol, cyfoeth a statws yn ogystal â rhinweddau milwrol.2 Nid i ganu mawl i arglwyddi yr oedd arfau‘n gyfyngedig, ychwaith, – fe‘u gwelir mewn cerddi i osgorddion ac i swyddogion, ac mewn cerddi mawl a cherddi ymffrost sy‘n darlunio‘r bardd ei hun fel rhyfelwr. Ac fe‘u defnyddid yn symbolaidd, yn ffigurol neu‘n drosiadol mewn amrediad eang o genres gan gynnwys canu crefyddol a cherddi i wragedd yn ogystal â chanu mawl i wrthrychau gwrywaidd. Nid yw‘n syndod fod y beirdd wedi gwneud defnydd mor helaeth o arfau yn eu cerddi. Mae croniclau megis Brut y Tywysogion yn tystio i hollbresenoldeb brwydro drwy gyfnod y Tywysogion, a‘r tywysogion eu hunain, fel llywodraethwyr canoloesol eraill, yn aml yn defnyddio dulliau arfog wrth adeiladu neu amddiffyn eu teyrnasoedd.3 Mynegwyd y ffaith 1 G.J Williams and E.J. -

3. Development Management Policies

Shropshire Council Site Allocations and Management of Development (SAMDev) Plan Pre-Adoption Version (Incorporating Inspector’s Modifications) Full Council 17th December 2015 3. Development Management Policies MD1 : Scale and Distribution of Development Further to the policies of the Core Strategy: 1. Overall, sufficient land will be made available during the remainder of the plan period up to 2026 to enable the delivery of the development planned in the Core Strategy, including the amount of housing and employment land in Policies CS1 and CS2. 2. Specifically, sustainable development will be supported in Shrewsbury, the Market Towns and Key Centres, and the Community Hubs and Community Cluster settlements identified in Schedule MD1.1, having regard to Policies CS2, CS3 and CS4 respectively and to the principles and development guidelines set out in Settlement Policies S1-S18 and Policies MD3 and MD4. 3. Additional Community Hubs and Community Cluster settlements, with associated settlement policies, may be proposed by Parish Councils following formal preparation or review of a Community-led Plan or a Neighbourhood Plan and agreed by resolution by Shropshire Council. These will be formally considered for designation as part of a Local Plan review. Schedule MD1.1: Settlement Policy Framework: County Town and Sub-regional Centre Shrewsbury Market Towns and Key Centres Oswestry Bishop’s Castle Ellesmere Cleobury Mortimer Whitchurch Bridgnorth Market Drayton Shifnal Wem Much Wenlock Minsterley/Pontesbury Broseley Ludlow Highley Craven Arms -

Salopian Recorder No.92

Diary Dates The newsletter of the Friends of Shropshire Archives, Saturday 20 October 2018 Saturday 17 November 2018 ARCHIVES First World War Showcase Day Much Wenlock Charter Celebrations SHROPSHIRE gateway to the history of Shropshire and Telford 10.00am - 4.00pm Shirehall, Abbey Foregate, Contact Much Wenlock Town Council Shrewsbury SY2 6ND www.muchwenlock-tc.gov.uk Free event! Saturday 27 October 2018 Saturday 24 November 2018 Arthur Allwood, Victoria County History Annual lecture Friends Annual Lecture Shropshire RHA and Horses in Early Modern Shropshire: for Dr Kate Croft - “Healthy and Expedient”: Childcare and KSLI, 1912-1919 Charity at the Shrewsbury Foundling Hospital 1759-1772 Service, for Pleasure, for Power? Page 2 Professor Peter Edwards 10.30am, £5 Shropshire Archives, Shrewsbury, SY1 2AQ 2.00pm, £5 donation requested For further details see www. Reasearching Central, Shrewsbury Baptist Church, 4 Claremont friendsofshropshirearchives.org.uk Street, Shrewsbury Myndtown Church Page 5 Tuesday 6 November 2018 Tuesdays, 22 January – 26 February 2019 Discover the Stories Behind the Stones House History Course Shrewsbury at work The Beautiful Burial Ground project is offering a FREE Contact [email protected] for training session at Shropshire Archives for those further details interested in the stories told by our burial grounds. Page 8 This session will cover an introduction to the archive as well as how to use the archive to investigate the lives and stories in your local burial ground. To book your free place please get in touch with George at [email protected] or 01588 673041 10.30am - 12.30pm ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: The newsletter of the Friends of News Extra.. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Cabinet, 28/11/2018 10:30

Public Document Pack Cabinet Meeting Venue Council Chamber - County Hall, Llandrindod Wells, Powys Meeting date Wednesday, 28 November 2018 County Hall Llandrindod Wells Meeting time Powys 10.30 am LD1 5LG For further information please contact Stephen Boyd 22 November 2018 01597 826374 [email protected] The use of Welsh by participants is welcomed. If you wish to use Welsh please inform us by noon, two working days before the meeting AGENDA 1. APOLOGIES To receive apologies for absence. 2. MINUTES To authorise the Chair to sign the minutes of the last meeting held as a correct record. (Pages 5 - 8) 3. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST To receive any declarations of interest from Members relating to items to be considered on the agenda. 4. COUNCIL TAX BASE FOR 2019-2020 To consider a report by County Councillor Aled Davies, Portfolio Holder for Finance, Countryside and Transport. (Pages 9 - 16) 5. FINANCIAL OVERVIEW AND FORECAST AS AT 31ST OCTOBER 2018 To consider a report by County Councillor Aled Davies, Portfolio Holder for Finance, Countryside and Transport. (Pages 17 - 20) 6. REVIEW OF FARMS POLICY To consider a report by the Leader, County Councillor Rosemarie Harris. (Pages 21 - 52) 7. LOCAL AUTHORITY LOTTERY To consider a report by the Leader, County Councillor Rosemarie Harris. (Pages 53 - 62) 8. SCHOOLS CASHLESS PROJECT - CLOSING REPORT To consider a report by County Councillor Phyl Davies Portfolio Holder for Highways, Recycling and Assets. (Pages 63 - 70) 9. PROPERTIES ISSUES IN HAY-ON-WYE To consider a report by County Councillor Phyl Davies, Portfolio Holder for Highways, Recycling and Assets. -

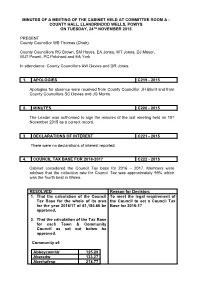

Minutes Template

MINUTES OF A MEETING OF THE CABINET HELD AT COMMITTEE ROOM A - COUNTY HALL, LLANDRINDOD WELLS, POWYS ON TUESDAY, 24TH NOVEMBER 2015 PRESENT County Councillor WB Thomas (Chair) County Councillors RG Brown, SM Hayes, EA Jones, WT Jones, DJ Mayor, WJT Powell, PC Pritchard and EA York In attendance: County Councillors AW Davies and DR Jones. 1. APOLOGIES C219 - 2015 Apologies for absence were received from County Councillor JH Brunt and from County Councillors SC Davies and JG Morris. 2. MINUTES C220 - 2015 The Leader was authorised to sign the minutes of the last meeting held on 10th November 2015 as a correct record. 3. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST C221 - 2015 There were no declarations of interest reported. 4. COUNCIL TAX BASE FOR 2016-2017 C222 - 2015 Cabinet considered the Council Tax base for 2016 – 2017. Members were advised that the collection rate for Council Tax was approximately 99% which was the fourth best in Wales. RESOLVED Reason for Decision: 1. That the calculation of the Council To meet the legal requirement of Tax Base for the whole of its area the Council to set a Council Tax for the year 2016/17 of 61,185.66 be Base for 2016-17 approved, 2. That the calculation of the Tax Base for each Town & Community Council as set out below be approved. Community of: Abbeycwmhir 125.29 Aberedw 133.27 Aberhafesp 218.77 Abermule with Llandyssil 719.64 Banwy 317.56 Bausley with Criggion 359.43 Beguildy 375.78 Berriew 734.61 Betws Cedewain 230.98 Brecon 3441.49 Bronllys 424.73 Builth Wells 1070.10 Cadfarch 446.80 Caersws 704.77 Carno 351.15 -

Holdgate at Shropshire Archives

Sources for HOL(D)GATE This guide gives a brief introduction to the variety of sources available for the parish of Holdgate at Shropshire Archives. Printed sources: General works - These may also be available at Much Wenlock library Eyton, Antiquities of Shropshire Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological Society Shropshire Magazine Trade Directories which give a history of the town, main occupants and businesses, 1828-1941 Victoria County History of Shropshire – Vol X Parish Packs Monumental Inscriptions Small selection of more specific texts (search www.shropshirearchives.org.uk for a more comprehensive list) q P55.5 Probate inventories of the Clee Hills QT55 v.f. Bishops Transcripts 1660-1669 C64 Reading Room Antiquities of Shropshire Vol. IV – Robert Eyton C61 Reading Room The misericord at Holdgate parish church – Peter Klein Church of The Holy Trinity, Holdgate 6009/104 Sources on microfiche or film: Parish and non-conformist church registers Baptisms Marriages / Banns Burials Church of the Holy 1660-1820 1660-1796 1660-1812 Trinity 1813-1837 on 1813-1837 on microfilm microfilm Methodist records can be accessed with a readers ticket from Methodist Circuit Records Up to 1900, registers are on www.findmypast.co.uk Census returns 1841, 1851(indexed), 1861, 1871, 1881, 1891, 1901 Census returns for the whole country to 1911 can be looked at on the Ancestry website Maps Ordnance Survey maps 25” to the mile and 6 “to the mile, c1880, c1901 (OS reference: old series LXV.1 new series SO 5689 Tithe map of c 1840 and apportionment (list of owners/occupiers) Newspapers Shrewsbury Chronicle, 1772 onwards (NB from 1950 as originals only – Reader’s Ticket required) Shropshire Star, 1964 onwards Archives: To see these sources you need a Shropshire Archives Reader's Ticket. -

Landmap for Brecknock

THE CLWYD POWYS ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST Montgomeryshire LANDMAP Historic Landscape Aspect Technical Report CPAT Report No 804 CPAT Report No 804 Montgomeryshire LANDMAP Historic Landscape Aspect Technical Report W J Britnell and C H R Martin May 2006 Report for Powys County Council The Clwyd Powys Archaeological Trust 7a Church Street, Welshpool, Powys, SY21 7DL tel (01938) 553670, fax (01938) 552179 email [email protected] web www.cpat.org.uk EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Historic Landscape Aspect of the Montgomeryshire LANDMAP identified 102 separate aspect areas, ranging in size from 0.27 to 129.99 square kilometres and representing 12 different landscape patterns, at Level 3 in the current LANDMAP Information System handbook. The patterns represented are Irregular fieldscape (40 areas), Regular fieldscape (12 areas), Other fieldscape (6 areas), Woodland (7 areas), Marginal land (11 areas), Water & wetland (1 area), Nucleated settlement (14 areas), Non-nucleated settlement (1 area), Extractive industry (1 area), Processing/manufacturing (3 area), Designed landscape (1 area) and Recreational (1 area). Historic Landscape aspect areas were identified using a number of digital and paper data sources, verified by rapid field visiting and drawn as a digital map against a 1:10,000 OS map background attached to a database of supporting information. These digital elements and this Technical Report contain the results of the Montgomeryshire LANDMAP study and were submitted to Powys County Council and the Countryside Council for Wales on completion of the project. Montgomeryshire’s historic landscape has evolved over the course of many millennia and shows considerable variety within one of Wales’ largest historical counties. -

Things to See and Do

over the river, where every With its mix of Medieval, and landscape of the area the church. Further afield, spring The Green Man must Georgian and Victorian where you can Meet the but which also make a great t defeat the Frost Queen for architecture, Much Wenlock Mammoth – a full size day out is the Severn Valley there to be summer in the is a must on your ‘to do’ list. replica of the skeleton Railway at Bridgnorth, Clun Valley. This annual Walk along the High Street found at Condover. The The Judge’s Lodgings’ at Church Stretton, nestled in the Shropshire Hills celebration in May is the to browse the galleries, book exhibition also includes Presteigne, Powys Castle, high point of the town’s and antique shops. Visit a film panorama with home of the Earl of Powys, of independent retailers, whether on foot, by bike or famous Green Man Festival, the museum in the Market spectacular views of the near Welshpool, the offering a top-quality even aiming for the sky; the which also includes The Square to discover the Shropshire Hills. After that, fascinating museums of the Michaelmas fair, Bishops Castle shopping experience along Long Mynd enjoys some of Clun Mummers doing battle town’s heritage and links to explore the centre’s 30-acre Ironbridge Gorge and of with a tempting selection of the best thermals in Europe, For 800 years Welsh drovers heritage displays and Visitor in the Square, as well as the modern Olympic Games. Onny Meadows site, which course, the County town of Carding Mill Valley and the Long Mynd Green Man Festival, Clun butchers, bakers, historic so is unrivalled for gliding, brought livestock along the Information Centre.