Walt Whitman: a Current Bibliography, Winter 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Contributions of James F. Neill to the Development of the Modern Ameri Can Theatrical Stock Company

This dissertation has been 65—1234 microfilmed exactly as received ZUCCHERO, William Henry, 1930- THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF JAMES F. NEILL TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE MODERN AMERI CAN THEATRICAL STOCK COMPANY. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1964 Speech—Theater University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan Copyright by William Henry Zucchero 1965 THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF JAMES F. NEILL TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE MODERN AMERICAN THEATRICAL STOCK COMPANY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By William Henry Zucchero, B.S., M.A. * * * * * $ The Ohio State University 1964 Approved by PLEASE NOTE: Plates are not original copy. Some are blurred and indistinct. Filmed as received. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS, INC. PREFACE Appreciation is extended to the individuals, named below, for the aid each has given in the research, prepara tion, and execution of this study. The gathering of pertinent information on James F. Neill, his family, and his early life, was made possible through the efforts of Mrs. Eugene A. Stanley of the Georgia Historical Society, Mr. C. Robert Jones (Director, the Little Theatre of Savannah, Inc.), Miss Margaret Godley of the Savannah Public Library, Mr. Frank Rossiter (columnist, The Savannah Morning News). Mrs. Gae Decker (Savannah Chamber of Commerce), Mr. W. M. Crane (University of Georgia Alumni Association), Mr. Don Williams (member of Sigma Alpha Epsilon— Neill’s college fraternity), and Mr. Alfred Kent Mordecai of Savannah, Georgia. For basic research on the operation of the Neill company, and information on stock companies, in general, aid was provided by Mrs. -

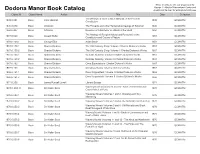

Catalog Records April 7, 2021 6:03 PM Object Id Object Name Author Title Date Collection

Catalog Records April 7, 2021 6:03 PM Object Id Object Name Author Title Date Collection 1839.6.681 Book John Marshall The Writings of Chief Justice Marshall on the Federal 1839 GCM-KTM Constitution 1845.6.878 Book Unknown The Proverbs and other Remarkable Sayings of Solomon 1845 GCM-KTM 1850.6.407 Book Ik Marvel Reveries of A Bachelor or a Book of the Heart 1850 GCM-KTM The Analogy of Religion Natural and Revealed, to the 1857.6.920 Book Joseph Butler 1857 GCM-KTM Constitution and Course of Nature 1859.6.1083 Book George Eliot Adam Bede 1859 GCM-KTM 1867.6.159.1 Book Charles Dickens The Old Curiosity Shop: Volume I Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.159.2 Book Charles Dickens The Old Curiosity Shop: Volume II Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.160.1 Book Charles Dickens Nicholas Nickleby: Volume I Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.160.2 Book Charles Dickens Nicholas Nickleby: Volume II Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.162 Book Charles Dickens Great Expectations: Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.163 Book Charles Dickens Christmas Books: Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1868.6.161.1 Book Charles Dickens David Copperfield: Volume I Charles Dickens's Works 1868 GCM-KTM 1868.6.161.2 Book Charles Dickens David Copperfield: Volume II Charles Dickens's Works 1868 GCM-KTM 1871.6.359 Book James Russell Lowell Literary Essays 1871 GCM-KTM 1876.6. -

Reference Works in British and American Literature Second Edition

Reference Works in British and American Literature Second Edition James K. Bracken 1998 Libraries Unlimited, Inc. Englewood, Colorado Contents Acknowledgments xxix Fredrick Irving Anderson, 1877- Introduction xxxi 1947 10 Frequently Cited Works Maxwell Anderson, 1888-1959 .... 11 and Acronyms xxxvii Poul Anderson, 1926- 11 Sherwood Anderson, 1876-1941 ... 12 Andreas, late 9th century 13 Writers and Works Lancelot Andrewes, 1555-1626 ... 13 Lascelles Abercrombie, 1881-1938 . 1 Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, c. 1154 .... 13 Louis Adamic, 1899-1951 1 F. Anstey (Thomas Anstey Andy Adams, 1859-1935 1 Guthrie), 1865-1934 13 Henry (Brooks) Adams, 1838- Mary Antin (Grabau), 1881-1949 . 13 1918 1 John Arbuthnot, 1667-1735 14 John Turvill Adams, 1805-1882 .... 2 John Arden, 1930- 14 Leonie Adams (Fuller), 1899-1988 . 2 John Armstrong, 1709-1779 14 Oscar Fay Adams, 1855-1919 2 Martin Donisthorpe Armstrong, Samuel Hopkins Adams, 1871- 1882-1974 14 1958 2 Matthew Arnold, 1822-1888 14 Joseph Addison, 1672-1719 2 Harriette (Simpson) Arnow, 1908- George Ade; 1866-1944 3 1986 16 Aelfric, c. 955-c. 1010 3 T(imothy) S(hay) Arthur, 1809- James Agee, 1909-1955 3 1885 16 Conrad (Potter) Aiken, 1889- Nathan Asch, 1902-1964 16 1973 4 Sholem Asch, 1880-1957 16 William Harrison Ainsworth, Roger Ascham, 1515/16-1568 .... 16 1805-1882 4 John (Lawrence) Ashbery, 1927- ... 16 Mark Akenside, 1721-1770 4 Isaac Asimov, 1920-1992 17 Edward (Franklin) Albee, 1928- . 4- Gertrude (Franklin) Atherton, (Amos) Bronson Alcott, 1799-1888 . 5 1857-1948 17 Louisa May Alcott, 1832-1888 .... 5 William Attaway, 1911-1986 17 Richard (Edward Godfree) Margaret Atwood, 1939- 17 Aldington, 1892-1962 6 Louis (Stanton) Auchincloss, Thomas Bailey Aldrich, 1836-1907 . -

Literature and Americana

Catalogue 28 Literature and Americana Up-Country Letters Gardnerville, Nevada Catalogue Twenty-Eight Literature and Americana from Up-Country Letters Gardnerville, Nevada All items subject to prior sale. Shipping is extra and will billed at or near cost. Payment may be made with a check, PayPal, Visa, Mastercard, Discover. We will cheerfully work with institu- tions to accommodate accounting policies/constraints. Any item found to be disappointing may be returned within a week of receipt; please notify us if this is happening or if you need more time. Direct enquiries to: Mark Stirling, Up-Country Letters. PO Box 596, Gardnerville, NV 89410 530 318-4787 (cell); 775 392-1122 (land line) [email protected] www.upcole.com Christie Macdonald Jefferson Star of the musical stage in the early 1900’s, she married William W. Jefferson, son of the actor Joseph Jefferson, in 1901. “I am strong and self-reliant enough to make myself what I wish to be.” See Item 78 The cover: Map of the State of Nevada, 1866. Department of the Interi- or, General Land Office. See Item 51. Dedication copy, see Item 43 Hampshire) Library on the free endpaper of each volume, no other library markings. Light rub- 1. Arnold, Matthew. Carte de Visite Photograph. Imprint of Elliott and Fry. Bust portrait. bing, a little spotting and wrinkling, but a Fine, fresh copy. $100 Contemporary ownership initials dated May, 1868. The National Portrait Gallery lists this pose as 1870's. A Fine copy. $100 8. [California, Emigrant Trail] Smith, C.W. (Charles). Journal of a Trip to California. -

Partment), for Helping the Journal Stave Off Scholarly Extinction

Spring 2007 Volume VIII, Number 1 CONTENTS ESSAYS, AN INTERVIEW, AND A POEM A Poe Taster Daniel Hoffman 7 A Poe Death Dossier: Discoveries and Queries in the Death of Edgar Allan Poe Matthew Pearl 8 Politian’s Significance for Early American Drama Amy Branam 32 Sensibility, Phrenology, and “The Fall of the House of Usher” Brett Zimmerman 47 Interview with Benjamin Franklin Fisher IV Barbara Cantalupo 57 Sinking Under Iniquity Jeffrey A. Savoye 70 REVIEWS Lynda Walsh. Sins Against Science: The Scientific Media Hoaxes of Poe, Twain, and Others. Martha A. Turner 75 2 Bruce Mills. Poe, Fuller, and the Mesmeric Arts: Transition States in the American Renaissance. Adam Frank 82 Benjamin F. Fisher, Editor. Masques, Mysteries, and Mastodons: A Poe Miscellany. Thomas Bonner, Jr. 85 Harold Schechter. The Tell-Tale Corpse: An Edgar Allan Poe Mystery. Paul Jones 88 FEATURES Poe in Cyberspace by Heyward Ehrlich 91 Abstracts for PSA’s ALA Sessions 97 PSA Matters 103 In Memorial 105 Notes on Contributors 107 3 Letters from the Editors From Peter Norberg: Serving as coeditor of the Poe Review has been a rewarding experience both professionally and personally. I am grateful for the support we have received from Saint Joseph’s University and would like to thank Timothy R. Lannon, President, Brice Wachterhauser, Provost, and William Madges, Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, for their financial support and their commitment to scholarship in the humanities. I would also like to thank the officers of the Poe Studies Association, especially Paul C. Jones, Secretary-Treasurer, for his competent oversight of our budget and subscriptions, and Scott Peeples, President, for his thoughtful management of the transition of the Review back to the editorial stewardship of Barbara Cantalupo and Penn State University. -

1852-1930 Emily Jordan 1858-1936 a LIST of the RECORDS BELONGING to MR and MRS FOLGER in the FOLGER SHAKESPEARE LIBRARY Compiled

1852-1930 Emily Jordan 1858-1936 A LIST OF THE RECORDS BELONGING TO MR AND MRS FOLGER IN THE FOLGER SHAKESPEARE LIBRARY Compiled ca. 1965 ii INTRODUCTION The records of Mr and Mrs Folger which are in the Folger Shakespeare Library are only part of those which they must once have had. Certain kinds of papers, like the collection of booksellers' bills and receipts, have probably survived in their entirety. Others, like certain personal bills and letters, only sporadically. Mrs Folger sent ten cases of her . husband's books and papers to the Standard Oil, Company of New York in (See also her June 1932. Many of the documents now in the library were deposited Meridian Club before Mrs Folger's death; a battered label bears the note “Mr Henry C. Paper, 1933, p. 9, in Folger. Cancelled checks; receipted bills, miscellaneous unsorted papers Box 33) and scraps. These were removed from the closet in the cataloging room on September 26, 1935". More were added after Mrs Folger's death. Some, of the photographs were received from the estate of Mrs Folger, April 7, 1936. A.S.W Rosenbach, presented 3 scrapbooks made by Mr and Mrs Folger during their college days, Sep. 22, 1939. E.J. Dimock, a nephew, presented 2 notebooks and one scrapbook, Oct. 12, 1939. Miss Myers gave E.J. Rogers' correspondence with Mrs Folger, Sep. 22, 1960. The collection of records which thus found its way into the library had very little order and lay as a miscellaneous collection of crates, boxes, cartons and volumes. -

Brilliant Minds Wiki Spring 2016 Contents

Brilliant Minds Wiki Spring 2016 Contents 1 Rigveda 1 1.1 Text .................................................... 1 1.1.1 Organization ........................................... 2 1.1.2 Recensions ............................................ 2 1.1.3 Rishis ............................................... 3 1.1.4 Manuscripts ............................................ 3 1.1.5 Analytics ............................................. 3 1.2 Contents .................................................. 4 1.2.1 Rigveda Brahmanas ........................................ 5 1.2.2 Rigveda Aranyakas and Upanishads ............................... 5 1.3 Dating and historical context ....................................... 5 1.4 Medieval Hindu scholarship ........................................ 7 1.5 Contemporary Hinduism ......................................... 7 1.5.1 Atheism, Monotheism, Monism, Polytheism debate ....................... 7 1.5.2 Mistranslations, misinterpretations debate ............................ 8 1.5.3 “Indigenous Aryans” debate .................................... 8 1.5.4 Arya Samaj and Aurobindo movements .............................. 8 1.6 Translations ................................................ 8 1.7 See also .................................................. 8 1.8 Notes ................................................... 8 1.9 References ................................................. 9 1.10 Bibliography ................................................ 12 1.11 External links .............................................. -

Folger Shakespeare Library Amendment

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Folger Shakespeare Library (interior spaces and exterior of Hartman-Cox Addition) _(addendum to Folger Shakespeare Library (09-06-08-0015 6/23/69)_ Other names/site number: ______________________________________ Name of related multiple property listing: _______N/A____________________________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: __201 East Capitol Street, S.E.__________________________________ City or town: _Washington___________ State: ___D.C.________ County: ____________ Not For Publication: Vicinity: ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination -

Ada Rehan Papers Ms

Ada Rehan papers Ms. Coll. 191 Finding aid prepared by Kimberly Tully. Last updated on April 03, 2020. University of Pennsylvania, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts 1997 Ada Rehan papers Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Other Finding Aids........................................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 8 Incoming correspondence........................................................................................................................ 8 Memorabilia.......................................................................................................................................... -

Folger Shakespeare Library Amendment

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Folger Shakespeare Memorial Library (additional documentation) Other names/site number: ______________________________________ Name of related multiple property listing: N/A (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: 201 East Capitol Street, S.E. City or town: Washington State: DC County: ____________ Not For Publication: Vicinity: ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements -

The Theatre Magazine; an Analysis of Its Treatment of Selected Aspects of American Theatre

This dissertation has been 63-3305 microfilmed exactly as received MEERSMAN, Roger Leon, 1931- THE THEATRE MAGAZINE; AN ANALYSIS OF ITS TREATMENT OF SELECTED ASPECTS OF AMERICAN THEATRE. University of Illinois, Ph.D., 1962 Speech-Theater University Microfilms, Inc.. Ann Arbor. Michigan aa*" *i Copyright by ROGER LEON MEERSMAN 1963 _ < -.-• J-1'.-. v» •>; I, THE THEATRE MAGAZINE: AN ANALYSIS OF ITS TREATMENT OF SELECTED ASPECTS OF AMERICAN THEATRE BY ROGER LEON MEERSMAN B.A., St. Ambrose College, 1952 M.A. , University of Illinois, 1959 THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Speech in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois, 1962 Urbana, Illinois UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS THE GRADUATE COLLEGE September 20, 1962 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION Ttv Roger Leon Meersman FNTTTT.PX> The Theatre Magazine: An Analysis of Its Treatment of Selected Aspects of American Theatre BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE rw Doctor of Philosophy ./$<j^Y±4S~K Afc^r-Jfr (A<Vf>r In Charge of Thesis yrt rfnSSL•o-g^ . Head of Department Recommendation concurred inf Cw .MluJ^H, ^ya M< Committee ( WgJrAHJ- V'/]/eA}tx.rA on UP, ^A^k Final Examination! fl. ^L^^fcc^A f Required for doctor's degree but not for master's DS17 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I sincerely wish to thank the members of my committee, Professors Karl Wallace, Wesley Swanson, Joseph Scott, Charles Shattuck and Marvin Herrick for establishing high standards of scholarship and for giving me valuable advice in the courses I took from them. -

Critical Companion to Walt Whitman: a Literary Reference to His Life and Work

CRITICAL COMPANION TO Walt Whitman A Literary Reference to His Life and Work CHARLES M. OLIVER Critical Companion to Walt Whitman: A Literary Reference to His Life and Work Copyright © 2006 by Charles M. Oliver All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. An imprint of Infobase Publishing 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Oliver, Charles M. Critical companion to Walt Whitman : a literary reference to his life and work / Charles M. Oliver. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8160-5768-0 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Whitman, Walt, 1819–1892. 2. Poets, American—19th century— Biography. I. Title. PS3231.053 2005 811′.3—dc22 2005004172 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by Erika K. Arroyo Cover design by Cathy Rincon Chart by Sholto Ainslie Printed in the United States of America VB Hermitage 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. This book is dedicated to the memory of Professor Fred Eckman of Bowling Green State University and to the dozen students in his graduate seminar on Walt Whitman in the summer of 1966.