Bulletin Vol 49 No 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tame Valley to Heights

Along the Tame Valley to Heights Start: Millgate Car Park, Millgate, Delph Distance: 8.2 kilometres/5 miles Ascent: 270 metres/885 feet Time: 3 hours Introduction Starting from the quaint little village of Delph this easy, delightful walk sets out along the Tame Valley, where you will see rich evidence of the area’s historic and industrial past. At the head of the valley, you will pass through Denshaw, Saddleworth’s most northerly village, which has seen human activity since the Stone Age. Leaving the valley, the route now crosses farmland to the 18th century Heights Chapel, which has appeared in several films and television productions. Here you can enjoy a rest in the Heights Pub before making the final short descent back into Delph. Walk Description Nestled at the convergence of the Castleshaw and Denshaw valleys, Delph derives its name from the old English word ‘delf’, which means ‘quarry’. Bakestones were quarried in the Castleshaw Valley, just to the north of the village: the three-quarter inch thick quarried tiles were used to bake oatcakes and muffins. The area was probably first populated around the time that a Roman garrison was stationed at the Castleshaw Fort in AD79. From the late 1700s, the area supported the thriving textile industry, and the centre of the village has changed little since the early 19th century. The start point for this delightful walk is Millgate car park opposite the Co-operative Hall. Built in 1864, the hall is now a theatre and library and is managed by a local theatrical group called Saddleworth Players. -

Oldham School Nursing Clinical Manager Kay Thomas Based At

Oldham School Nursing Clinical Manager Kay Thomas based at Stockbrook Children’s Centre In the grounds of St Luke’s CofE Primary School Albion Street Chadderton Oldham OL9 9HT 0161 470 4304 School Nursing Team Leader Suzanne Ferguson based at Medlock Vale Children’s Centre The Honeywell Centre Hadfield Street Hathershaw Oldham, OL8 3BP 0161 470 4230 Email: [email protected] Below is a list of schools with the location and telephone number of your child’s School Nurse School – East Oldham / Saddleworth and Lees Beever Primary East / Saddleworth and Lees School Clarksfield Primary Nursing team Christ Church CofE (Denshaw) Primary Based at; Delph Primary Diggle School Beever Children's Centre Friezland Primary In the grounds of Beever Primary Glodwick Infants School Greenacres Primary Moorby St Greenfield Primary Oldham, OL1 3QU Greenhill Academy Harmony Trust Hey with Zion VC Primary T: 0161 470 4324 Hodge Clough Primary Holy Cross CofE Primary Holy Trinity CofE (Dobcross) School Horton Mill Community Primary Knowsley Junior School Littlemoor Primary Mayfield Primary Roundthorn Primary Academy Saddleworth School St Agnes CofE Primary St Anne’s RC (Greenacres) Primary St Anne’s CofE (Lydgate) Primary St Chads Academy St Edward’s RC Primary St Mary’s CofE Primary St Theresa’s RC Primary St Thomas’s CofE Primary (Leesfield) St Thomas’s CofE Primary (Moorside) Springhead Infants Willow Park The Blue Coat CofE Secondary School Waterhead Academy Woodlands Primary Oldham 6th form college Kingsland -

The London Gazette, November 20, 1908

8'.58« THE LONDON GAZETTE, NOVEMBER 20, 1908. In Parliament.—Session 1909. • pipes situate wholly .in the said parish-of OLDHAM CORPORATION. Butterworth, commencing at .or in the winding, shaft of the said Butterworth Hall Colliery and (New Waterworks, Wells, Boreholes, Pumping terminating at or in the Butterworth Ha.ll. Stations ! and Aqueducts; New Road and Pumping Station. Footpath; Discharge of Water into Streams; Work No. 4.—An aqueduct, conduit or line Power to Collect and Impound Water; of pipes, situate wholly in the said parish of Maintenance of Waterworks; Breaking up Butterworth, commencing at or in the Butter-, Streets and Roads and Application of Water worth Hall Pumping Station and terminating Provisions of the Public Health Acts; Con- at or in the south-west corner of the existing firmation of Agreement with Platt Brothers Piethorne reservoir of the Corporation and .and Company Limited; Agreements with numbered 432 on the T»Vs Ordnance Map of Owners, &c., of Lands as to Drainage and the said parish of Butterworth, published in Protection of Waters and Waterworks from 1894. Pollution, &c.; Bye-laws for Preventing Work No. 5.—A well, borehole and pumping Pollution of Water; New Works to be part station (hereinafter referred to as "the Delph. of Water Undertaking of Corporation; New Pumping Station "), situate wholly in the parish Tramways and Incidental Works; Gauge ; and urban district of Saddleworth, in the West Motive Power; New Tramways to be part of Riding of the county of York, in the enclosures Tramways Undertaking of Corporation; Work- numbered 1621 and 1622 on the ysW Ordnance ing Agreements and Traffic Arrangements; Map of the said parish, and urban district .of Omnibuses and Motor Cars on the Trolley Saddleworth, published in 1906. -

Saddlew Orth White Rose Society

Saddlew orth White Rose So ciety Newsletter 47 in the County of York Newsletter 48 Summer 2010 The Yorkshire flag flies alongside the Union flag over the Borough Civic Centre, at last recognising the fact that more than half the Borough is in Yorkshire. Yorkshire Day 2010 Harrogate who once again kindly donated their Yorkshire Tea. With exception of a three day event at This year for the first time the Yorkshire flag flew from Harewood House which is organised by the Yorkshire the Borough Civic Centre on Yorkshire Day 1st August. th Society, I believe that the Saddleworth event may be the On the 27 November the Lancashire flag will be biggest in the county.. flown. This is quite correct because the Borough spans part of Yorkshire and part of Lancashire in almost equal This year SWRS had plenty to celebrate. With the proportions (53% Yorkshire 47 % Lancashire). This has Borough, village signs stating “In the Historic West at last been acknowledged by the Borough Council. The Riding”, flying the Real County flag from the Borough area known as Greater Manchester was formed solely Civic Centre and the erecting of the first pair of Real for the purpose of local government administration and County boundary signs at Grains Bar not to replace the traditional counties. In 1988 Greater . Manchester, although not officially abolished, ceased to be an administrative authority and is now known as a ceremonial county. This year’s Yorkshire Day can only be said to be a tremendous success. There has been an increase in the number of stalls at the playing field each year the event has been held. -

Memories of a Massacre | History Today

15/10/2019 Memories of a Massacre | History Today Subscribe FEATURE Memories of a Massacre It is the 200th anniversary of the Peterloo Massacre. How have the events of that day been remembered? Katrina Navickas | Published in History Today Volume 69 Issue 8 August 2019 https://www.historytoday.com/archive/feature/memories-massacre 1/14 15/10/2019 Memories of a Massacre | History Today Obverse side of a medal commemorating the Peterloo Massacre, 19th century © Timothy Millett Collection/Bridgeman Images On Monday 16 August 1819, 60,000 men, women and children gathered for a mass rally in Manchester. They had progressed to St Peter’s Field on the southern edge of the town from the city’s working-class districts and the surrounding textile weaving regions, including Rochdale, Oldham and Stockport. Monday was the traditional day off for handloom weavers and other artisan workers, and the marchers wore their best clothes and symbols to create a festive atmosphere. Samuel Bamford, leading the contingent from the village of Middleton, described the start of their procession: Twelve of the most decent-looking youths … were placed at the front, each with a branch of laurel held in his hand, as a token of peace; then the colours [banners]: a blue one of silk, with inscriptions in golden letters, ‘Unity and Strength’, ‘Liberty and Fraternity’; a green one of silk, with golden letters, ‘Parliaments Annual’, ‘Suffrage Universal’. https://www.historytoday.com/archive/feature/memories-massacre 2/14 15/10/2019 Memories of a Massacre | History Today The main speaker, Henry ‘Orator’ Hunt, had travelled 200 miles north from London. -

English Radicalism and the Struggle for Reform

English Radicalism and the Struggle for Reform The Library of Sir Geoffrey Bindman, QC. Part I. BERNARD QUARITCH LTD MMXX BERNARD QUARITCH LTD 36 Bedford Row, London, WC1R 4JH tel.: +44 (0)20 7297 4888 fax: +44 (0)20 7297 4866 email: [email protected] / [email protected] web: www.quaritch.com Bankers: Barclays Bank PLC 1 Churchill Place London E14 5HP Sort code: 20-65-90 Account number: 10511722 Swift code: BUKBGB22 Sterling account: IBAN: GB71 BUKB 2065 9010 5117 22 Euro account: IBAN: GB03 BUKB 2065 9045 4470 11 U.S. Dollar account: IBAN: GB19 BUKB 2065 9063 9924 44 VAT number: GB 322 4543 31 Front cover: from item 106 (Gillray) Rear cover: from item 281 (Peterloo Massacre) Opposite: from item 276 (‘Martial’) List 2020/1 Introduction My father qualified in medicine at Durham University in 1926 and practised in Gateshead on Tyne for the next 43 years – excluding 6 years absence on war service from 1939 to 1945. From his student days he had been an avid book collector. He formed relationships with antiquarian booksellers throughout the north of England. His interests were eclectic but focused on English literature of the 17th and 18th centuries. Several of my father’s books have survived in the present collection. During childhood I paid little attention to his books but in later years I too became a collector. During the war I was evacuated to the Lake District and my school in Keswick incorporated Greta Hall, where Coleridge lived with Robert Southey and his family. So from an early age the Lake Poets were a significant part of my life and a focus of my book collecting. -

Saddleworth Historicalsociety Bulletin

Saddleworth Historical Society Bulletin Volume 49 Number 4 2019 Bulletin of the Saddleworth Historical Society Volume 49 Number 4 2019 Acting Chairman’s Address to the AGM 103 David Harrison The Development and Decline of Railways in the Saddleworth Area - Part 4 of 4 106 David Wharton-Street and Alan Young Saddleworth Freemasons - Lodge of Candour 1812 - 1851 124 Howard Lambert The Dobcross Loomworks Shunter or ‘The Dobcross Donkey’ 128 Peter Fox Arthur Hirst’s Diary - Errata 130 Index 132 Alan Schofield Cover Illustration: Emblem of the Freemason's Candour Lodge, Uppermill ©2019 Saddleworth Historical Society and individual contributors and creators of images. ii SHSB, VOL. 49, NO. 4, 2019 ACTING CHAIRMAN’S ADDRESS TO THE AGM 2019 David J. W. Harrison We are very sad to have to report that one of the new members of your committee, Peter Robinson, died last March. This was obviously a great loss to his family, and also to his friends, all to whom we extend our heart-felt condolences. Peter had only just commenced his service with the committee and was looking forward to help the Society grow. His loss is our sad loss. Your committee is still struggling to operate as well as we would wish due to a reduction in the number of trustees. There just aren’t enough to carry on the business of the Society properly. This year Charles Baumann has left the committee after many years of service when he undertook various tasks such as chairing lectures, organizing fund raising Flea Markets with me, publicising our events and other ventures as the need arose. -

Voice of Saddleworth News from Your Independent Councillors Denshaw, Delph, Dobcross, Diggle, Austerlands and Scouthead

Voice of Saddleworth News from your Independent Councillors Denshaw, Delph, Dobcross, Diggle, Austerlands and Scouthead SADDLEWORTH DESERVES BETTER! Vote For Change on May 22 Nikki Kirkham a Voice for Saddleworth Life-long Delph resident Nikki Kirkham, against the house-building agenda is standing as a Saddleworth that is threatening the landscape and Independent candidate in the local character of Saddleworth. She says: elections on May 22. Born in "We urgently need a tougher planning Denshaw, Nikki has lived in Delph regime and greater control at a local since she was three years old. level. We must protect our green belt and its natural beauty - not just for A working mum, Nikki is leader of the ourselves but also for our children. At Delph Methodist Cubs, a member of the same time we desperately need the Wake-Up Delph Committee (which affordable housing for first time buyers organises Party in The Park every and the elderly - something apparently year), and represents Delph and Den- forgotten by the Oldham planners. shaw on Saddleworth Parish Council. "All three political parties at Oldham She is sick of point-scoring party have consistently neglected politics and has chosen to be an Saddleworth. I will not be bound by independent so she can focus on the Oldham party politices. If you elect me, Nikki believes Saddleworth needs of Saddleworth residents. I’ll fight to get a better deal for deserves a better deal. If elected, Nikki promises to fight Saddleworth." IT'S A TWO HORSE RACE! Only 57 Votes Needed to Win In both the 2011 and 2012 borough elections only a handful of votes separated the Saddleworth Independents and the Liberal Democrat candidates. -

The Manchester Observer: Biography of a Radical Newspaper

Article The Manchester Observer: biography of a radical newspaper Poole, Robert Available at http://clok.uclan.ac.uk/28037/ Poole, Robert ORCID: 0000-0001-9613-6401 (2019) The Manchester Observer: biography of a radical newspaper. Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, 95 (1). pp. 31-123. ISSN 2054-9318 It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. http://dx.doi.org/10.7227/BJRL.95.1.3 For more information about UCLan’s research in this area go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/researchgroups/ and search for <name of research Group>. For information about Research generally at UCLan please go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/research/ All outputs in CLoK are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including Copyright law. Copyright, IPR and Moral Rights for the works on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the policies page. CLoK Central Lancashire online Knowledge www.clok.uclan.ac.uk i i i i The Manchester Observer: Biography of a Radical Newspaper ROBERT POOLE, UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL LANCASHIRE Abstract The newly digitised Manchester Observer (1818–22) was England’s leading rad- ical newspaper at the time of the Peterloo meeting of August 1819, in which it played a central role. For a time it enjoyed the highest circulation of any provincial newspaper, holding a position comparable to that of the Chartist Northern Star twenty years later and pioneering dual publication in Manchester and London. -

Bulletin Vol 48 No 4

Saddleworth Historical Society Bulletin Volume 48 Number 4 2018 Bulletin of the Saddleworth Historical Society Volume 48 Number 4 2018 Secretary’s Address to the AGM 103 David Harrison Manor House, Churchfields, Dobcross, - A Reappraisal 105 Mike Buckley Saddleworth Notices and Reports from The Leeds Intelligencer: Part 5, 1979 - 1800 118 Howard Lambert Index 124 Alan Schofield Cover Illustration: The Manor House, Dobcross David JW Harrison ©2018 Saddleworth Historical Society and individual contributors and creators of images. ii SHSB, VOL. 48, NO. 4, 2018 SECRETARY’S ADDRESS TO THE AGM 2018 David J. W. Harrison We are most saddened to have to report that one of your committee, Tony Wheeldon, died sudden- ly last week (3 Oct.). This was obviously a great loss to his family, and also to his many friends, all to whom we extend our heart-felt condolences. Tony has been of great help to the Society during his all too short a tenure as committee member, taking on all sorts of tasks, particularly those of a physical nature now becoming beyond the reach of some of us. The Society is in a poorer state for his passing. Your committee is still struggling to operate as well as we would wish through lack of committee members. There just aren’t enough to carry on the business of the Society properly. Recent fall outs from the committee include our hard working publicity officer, Charles Baumann, who has resigned due to family and other commitments however he has intimated that he would be available to help out on occasion subject to his availability from his other extensive interests. -

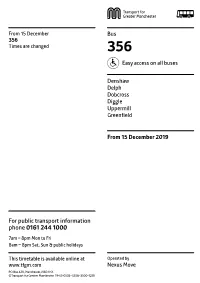

356 Times Are Changed 356

From 15 December Bus 356 Times are changed 356 Easy access on all buses Denshaw Delph Dobcross Diggle Uppermill Greenfield From 15 December 2019 For public transport information phone 0161 244 1000 7am – 8pm Mon to Fri 8am – 8pm Sat, Sun & public holidays This timetable is available online at Operated by www.tfgm.com Nexus Move PO Box 429, Manchester, M60 1HX ©Transport for Greater Manchester 19-SC-0535–G356–3500–1219 Additional information Alternative format Operator details To ask for leaflets to be sent to you, or to request Nexus Move large print, Braille or recorded information 22 Old Street, Ashton-under-Lyne, phone 0161 244 1000 or visit www.tfgm.com Manchester OL6 6LB Telephone 0161 331 2989 Easy access on buses Journeys run with low floor buses have no Travelshops steps at the entrance, making getting on Ashton Bus Station and off easier. Where shown, low floor Mon to Fri 7am to 5.30pm buses have a ramp for access and a dedicated Saturday 8am to 5.30pm space for wheelchairs and pushchairs inside the Sunday* Closed bus. The bus operator will always try to provide Oldham Bus Station easy access services where these services are Mon to Fri 7am to 5.30pm scheduled to run. Saturday 8am to 5.30pm Sunday* Closed Using this timetable *Including public holidays Timetables show the direction of travel, bus numbers and the days of the week. Main stops on the route are listed on the left. Where no time is shown against a particular stop, the bus does not stop there on that journey. -

The Queen Caroline Affair: Politics As Art in the Reign of George IV Author(S): Thomas W

The Queen Caroline Affair: Politics as Art in the Reign of George IV Author(s): Thomas W. Laqueur Source: The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 54, No. 3 (Sep., 1982), pp. 417-466 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1906228 Accessed: 06-03-2020 19:28 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Modern History This content downloaded from 130.132.173.181 on Fri, 06 Mar 2020 19:28:02 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The Queen Caroline Affair: Politics as Art in the Reign of George IV* Thomas W. Laqueur University of California, Berkeley Seldom has there been so much commotion over what appears to be so little as in the Queen Caroline affair, the agitation on behalf of a not- very-virtuous queen whose still less virtuous husband, George IV, want- ed desperately to divorce her. During much of 1820 the "queen's busi- ness" captivated the nation. "It was the only question I have ever known," wrote the radical critic William Hazlitt, "that excited a thor- ough popular feeling.