USSOUTHCOM Posture 2008 Pressv2.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

US Southern Command Demonstrates Interagency Collaboration, but Its

United States Government Accountability Office Report to the Chairman, Subcommittee GAO on National Security and Foreign Affairs, Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, House of Representatives July 2010 DEFENSE MANAGEMENT U.S. Southern Command Demonstrates Interagency Collaboration, but Its Haiti Disaster Response Revealed Challenges Conducting a Large Military Operation GAO-10-801 July 2010 DEFENSE MANAGEMENT Accountability Integrity Reliability U.S. Southern Command Demonstrates Interagency Highlights Collaboration, but Its Haiti Disaster Response Highlights of GAO-10-801, a report to the Revealed Challenges Conducting a Large Military Chairman, Subcommittee on National Security and Foreign Affairs, Committee Operation on Oversight and Government Reform, House of Representatives Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found U.S. Southern Command SOUTHCOM demonstrates a number of key practices that enhance and (SOUTHCOM) has been cited as sustain collaboration with interagency and other stakeholders toward having mature interagency achieving security and stability in the region. SOUTHCOM coordinated with processes and coordinating interagency partners to develop mutually reinforcing strategies, including its mechanisms. As evidenced by the 2009 Theater Campaign Plan and its 2020 Command Strategy. In addition, earthquakes that shook Haiti in January 2010, the challenges that SOUTHCOM focuses on leveraging the capabilities of various partners, SOUTHCOM faces require including interagency and international partners, and nongovernmental and coordinated efforts from U.S. private organizations. For example, at SOUTHCOM’s Joint Interagency Task government agencies, international Force South, resources are leveraged from the Department of Defense, U.S. partners, and nongovernmental and law enforcement and intelligence agencies, and partner nations to disrupt private organizations. This report illicit trafficking activities. -

Southcom Opord 600X-01 Joint Task Force – Bravo – Growing Resolve

FOUO—TRAINING PURPOSES ONLY DAU—CON 334 HEADQUARTERS, US SOUTHERN COMMAND Miami, FL USSOUTHCOM OPORD 600X-01 JOINT TASK FORCE – BRAVO – GROWING RESOLVE (U) REFERENCES*: a. (S) CDRUSSOUTHCOM OPLAN 600X, Protection of National Security Interests 1 Jan 201X.* b. (S) CDRUSSOUTHCOM DEPORD 600X, 1 Feb 201X.* c. (U) JP 5-0 Joint Operation Planning, 11 Aug 2011. d. (U) JP 2-03 Geospatial Intelligence Support to Joint Operations, 31 October 2012 e. JP 3-06, Joint Urban Operations, 20 November 2013 f. JP 3-07.4, Joint Counterdrug Operations, 14 August 2013 g. (U) JP 3-10 Joint Security Operations in Theater, 13 November 2014 h. (U) JP 3-22 Foreign Internal Defense, 12 July 2010. a. (S) Order of Battle (CINC OB).* b. Map, NIMA series XXXX, sheet reference e, scale 1:1,000,000. * denotes fictitious plans/orders or documents; included to provide realism to training products. 1. Situation a. General (1) U.S. and Honduran forces have conducted combined training exercises since 1965. In 1983, the Honduran government requested an increase in the size and number of those exercises, and as a result, Joint Task Force-Bravo (JTF-B) was established in August 1984. JTF-B was established to exercise command and control of U.S. Forces and exercises in the Republic of Honduras, and is a subordinate command of the United States Southern Command (USSOUTHCOM). Before being designated JTF-B in 1984, this task force was known as JTF-11 and then as JTF-Alpha. Following the events of September 11, 2001 and the Global War on Terror; the size/footprint of JTF-B slowly reduced to a fraction of what it once was as forces were redeployed to the Middle East. -

Reconstruction After Hurricane Mitch

98-1030 F CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Central America: Reconstruction After Hurricane Mitch Updated October 12, 1999 Lois McHugh, Coordinator Analyst in International Relations Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service The Library of Congress ABSTRACT The United States and the international community have launched a major relief and reconstruction response to the devastation in Central America caused by Hurricane Mitch (October 26-November 5, 1998). This paper provides background on conditions in the region both before and after the hurricane. It identifies the humanitarian and reconstruction aid provided by the United States and the international community and discusses the future course of the reconstruction effort. The President requested an emergency supplemental of $955.5 million on February 16, 1999 to pay for the U.S. effort (which includes reconstruction aid to Caribbean countries and Colombia). P.L. 106-31 appropriated $999.9 million for reconstruction programs. The supplemental request did not include trade expansion effort. Trade provisions are included in a Senate bill, S. 371, the Caribbean and Central American Relief Act, introduced on February 4, and its companion bill, H.R. 984, introduced on March 4 and reported to the full committee on May 18. The Administration trade bill (H.R. 1834) was introduced on May 18. This report will not be updated again. Central America: Reconstruction after Hurricane Mitch Summary On February 16, the Administration transmitted an emergency supplemental request for $955.5 million to provide reconstruction assistance to the Central American countries devastated last Fall by Hurricane Mitch. The supplemental did not include any of the trade expansion provisions which the Administration has proposed previously, and which the Central American countries include as their highest priority. -

Latin America – Storms DECEMBER 11, 2020

Fact Sheet #8 Fiscal Year (FY) 2021 Latin America – Storms DECEMBER 11, 2020 SITUATION AT A GLANCE 205 7.3 404,500 183,000 MILLION Reported Deaths in Latin Estimated People Affected Estimated People in Official and Estimated Houses Damaged America due to Eta and Iota in Guatemala, Honduras, Unofficial Emergency Shelters or Destroyed in Guatemala, and Nicaragua in Guatemala and Honduras Honduras, and Nicaragua UN – Dec. 2, 2020 UN – Dec. 4, 2020 CONRED, COPECO – Dec. 2, 2020 UN – Dec. 4, 2020 The effects of Hurricanes Eta and Iota are expected to worsen food insecurity in Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua in the coming months, with 3 million people currently projected as experiencing severe acute food insecurity. The U.S. Ambassador to Nicaragua visits Puerto Cabezas, where USAID/BHA A partner UNICEF delivers WASH assistance to affected households. USAID deactivates the DART and RMT; USAID/BHA staff continue to manage humanitarian response activities from Central America and Washington, D.C. TOTAL U.S. GOVERNMENT HUMANITARIAN FUNDING USAID/BHA1 $23,850,708 For the Latin America Storms Response in FY 2021 DoD2 $7,060,000 For complete funding breakdown with partners, see detailed chart on page 6 Total $30,910,708 1 USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (USAID/BHA). Funding figures reflect committed and obligated funding as of December 11, 2020. Total comprises a subset of the nearly $48 million in publicly announced USAID/BHA funding to the Latin America and Caribbean storms response. 2 U.S. Department of Defense (DoD). Funding figures reflect funding as of December 11, 2020. 1 TIMELINE KEY DEVELOPMENTS Nov. -

Boletín Informativo 1

INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION ANDPROMOTION Newsletter No. IV Members of the Diplomatic body and International Organizations inspected the damage caused from Eta and Iota in the Sula Valley The ambassadors of Chile, European Union, Taiwan, Spain, Brazil, Germany and Japan carried out an aerial tour, to verify on site the damage left by the storms Eta and Iota in the Sula valley. The representatives of countries and organizations that want to USAID cooperate, observed the damage made in municipalities of Villanueva, Potrerillos, Pimienta, San Manuel and Choloma; also the suburbs of La Planeta, Céleo Gonzales, Rivera Hernández, Chamelecón of the city of San Pedro Sula. Secretary of foreign affairs Lisandro Rosales accompanied the diplomats, who visited different zones of the department of Cortés, where they evidenced the damage that occurred and the work that is being done for the reconstruction. In the previous bulletin it was reported about the X-ray that President Juan Orlando Hernández, exposed on the situation in the country and the need for humanitarian aid and initiation of reconstruction efforts. “It is sad that the most productive area of the country and the most important industrial zone of Central America is affected in this way”, lamented, the Secretary. Joint Task Force-Bravo |cancilleriaHN USAID assigned USD 8.5 million dollars in humanitarian aid for Honduras The United States Government through the USAID Humanitarian Assistance Office, since the beginning of the disasters left by storms Eta and Iota, has been working hand in hand with strategic partners to provide food, hygiene supplies, blankets, water and other relief “Helping those in need is a U.S. -

2020 11 24 USAID-BHA Latin America Storms Fact Sheet #3

Fact Sheet #3 Fiscal Year (FY) 2021 Latin America – Storms NOVEMBER 24, 2020 SITUATION AT A GLANCE 171 5.2 329,700 $69.2 MILLION MILLION Reported Deaths in Latin Estimated People Affected Estimated People in Funding Requested for America due to Eta by Eta and Iota in Central Emergency Shelters in Response to Eta in America Guatemala, Honduras, and Honduras Nicaragua UN – Nov. 19, 2020 UN – Nov. 20, 2020 UN – Nov. 20, 2020 UN – Nov. 19, 2020 USAID/BHA supports humanitarian air bridge to transport relief commodities between Colombia’s storm-affected islands of San Andrés and Providencia. Persistent rain and flooding continue to hinder response and isolate communities in Guatemala, while JTF-Bravo supports delivery of humanitarian supplies across A the country. CABEI, IDB, and the World Bank announce financial support plan for early recovery and reconstruction efforts across Latin American countries impacted by Hurricanes Eta and Iota. TOTAL U.S. GOVERNMENT HUMANITARIAN FUNDING USAID/BHA1 $1,106,872 For the Latin America Storms Response in FY 2021 DoD2 $2,061,618 For complete funding breakdown with partners, see detailed chart on page 6 Total $3,168,490 1 USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (USAID/BHA). Funding figures reflect committed and obligated funding as of November 24, 2020. Total comprises a subset of the more than $17 million in publicly announced USAID/BHA funding to the Latin America and Caribbean storms response 2 U.S. Department of Defense (DoD). Funding figures reflect funding as of November 14, 2020. 1 TIMELINE KEY DEVELOPMENTS Nov. 3, 2020 USAID Supports Humanitarian Air Bridge to Transport Eta makes landfall over Supplies Between Colombia’s Storm-Affected Islands Nicaragua’s northeastern coast as a Category 4 Relief organizations continue to assess the extent of damages from hurricane Hurricanes Eta and Iota on Colombia’s San Andrés and Providencia islands, Nov. -

Posture Statement of General Douglas M. Fraser

POSTURE STATEMENT OF GENERAL DOUGLAS M. FRASER, UNITED STATES AIR FORCE COMMANDER, UNITED STATES SOUTHERN COMMAND BEFORE THE 112TH CONGRESS SENATE ARMED SERVICES COMMITTEE 6 MARCH 2012 UNITED STATES SOUTHERN COMMAND 1 Introduction Chairman Levin, Senator McCain, distinguished members of the Committee: thank you for the opportunity to appear before you today to report on the posture, security concerns, and future direction of United States Southern Command. Within the context of modest funding, we continue to accomplish our primary objective of defending the United States while also promoting regional security and enduring partnerships. The key to our defense-in-depth approach to Central America, South America, and the Caribbean has been persistent, sustained engagement, which supports the achievement of U.S. national security objectives by strengthening the security capacities of our partner nations. Militaries in our area of responsibility (AOR) are increasingly capable, professionalized, and rank among the most trusted institutions in many countries in the region.1 Interagency coordination is the foundation of United States Southern Command’s approach. Our relatively lean budget necessitates that we embrace innovative techniques to accomplish our mission; we do so by leveraging the capabilities and resources of our partners within the region, the U.S. government, and our command. Thirty-three interagency representatives and foreign liaison officers from five countries are integrated into our command, allowing us to capitalize on in-house expertise and align our engagement activities within U.S. government frameworks. We are continuing to refine our organizational model, but the guiding principle remains unchanged: we support a comprehensive interagency approach that employs whole-of-government solutions to address the complex challenges in the region. -

NSIAD-88-220 Honduran Deployment: Controls Over U.S. Military

United States General Accounting Office Report to Congressional Requesters . September 1988 HONDURAN DEPLOYMENT- Controls Over U.S. Military Equipment and Supplies l GAO/NSIAD-8&220 1 United States General Accounting Office GAO Washington, D.C. 20548 National Security and International Affairs Division B-218801 September 29, 1988 Congressional Requesters During March 1988, the U.S. Army deployed almost 3,000 U.S. combat troops and tons of equipment and supplies to the Republic of Honduras for an emergency deployment readiness exercise called GOLDEN PHEASANT. Various members of Congress became concerned that some of the equipment and supplies accompanying US. troops would be diverted to the Nicaraguan Democratic Resistance (Contra) forces. We reviewed Exercise GOLDEN PHEASANT to determine whether U.S. combat troops had diverted any equipment and supplies to the Contra forces. This report responds to requests received from the Chairmen of the Committees and members of Congress listed at the end of this letter. Based on our review of internal control documents and physical verifi- cation of organizational inventories, we concluded that military prop- erty had either been expended during Exercise GOLDEN PHEASANT or returned to the United States. Military property deployed to Honduras from Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and Fort Ord, California, included ammunition, explosives, vehicles, weapon systems, sensitive items (indi- vidual weapons and night vision devices), medical supplies, rations. and contingency stocks. We were unable to absolutely verify the return of two vehicles belonging to the 82nd Airborne Division because documen- tation provided by Division officials did not contain adequate identifica- tion data. Based on our observations at training locations in Honduras! we believe that the nature of the deployment as well as the on-site controls made it unlikely that any military property was diverted to the Contras. -

Southcoma Half-Century of Service Southcom50 Former SOUTHCOM

SOUTHCOMA HALF-CENTURY OF SERVICE SOUTHCOM50 Former SOUTHCOM Commanders Gen. Andrew P. O’Meara Gen. Robert W. Porter, Jr. USA, June 1963 – Feb. 1965 USA, Feb. 1965 – Feb. 1969 Gen. George R. Mather Gen. George V. Underwood Gen. William B. Rosson Lt. Gen. Dennis P. McAuliffe Lt. Gen. Wallace H. Nutting USA, Feb. 1969 – Sept. 1971 USA, Sept. 1971 – Jan. 1973 USA, Jan. 1973 – July 1975 USA, Aug. 1975 – Sept. 1979 USA, Oct. 1979 – May 1983 Gen. Paul F. Gorman Gen. John R. Galvin Gen. Frederick F. Woerner Gen. Maxwell R. Thurman Gen. George A. Joulwan USA, May 1983 – March 1985 USA, March 1985 – June 1987 USA, June 1987 – July 1989 USA, Sept. 1989 – Nov. 1990 USA, Nov. 1990 – Nov. 1993 Gen. Barry R. McCaffrey Gen. Wesley K. Clark Gen. Charles E. Wilhelm Gen. Peter Pace Maj. Gen. Gary D. Speer USA, Feb. 1994 – Feb. 1996 USA, July 1996 – July 1997 USMC, Sept. 1997 – Sept. 2000 USMC, Sept. 2000 – Sept. 2001 (Acting), USA, Oct. 2001 – Aug. 2002 Gen. James T. Hill Gen. Bantz J. Craddock Adm. James G. Stavridis Gen. Douglas M. Fraser USA, Aug. 2002 – Nov. 2004 USA, Nov. 2004 – Oct. 2006 USN, Oct. 2006 – June 2009 USAF, Oct. 2009 – Nov. 2012 SOUTHCOM ALL PHOTOS COURTESY SOUTHCOM50 DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE UNITED STATES SOUTHERN COMMAND OFFICE OF THE COMMANDER 9301 NW 33RD STREET DORAL, FL 33172-1202 I am honored to serve as Combatant Commander as U.S. Southern Command celebrates its 50th anniversary. I hope you enjoy reading about the command’s accomplishments, which are a reflection of the outstanding service members and civilian employees who work tirelessly to support our mission. -

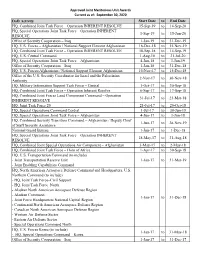

Approved Joint Meritorious Unit Awards Current As Of

Approved Joint Meritorious Unit Awards Current as of: September 30, 2020 DoD Activity Start Date to End Date HQ, Combined Joint Task Force – Operation INHERENT RESOLVE 15-Sep-19 to 14-Sep-20 HQ, Special Operations Joint Task Force – Operation INHERENT 1-Sep-19 to 15-Jun-20 RESOLVE Office of Security Cooperation – Iraq 1-Jan-19 to 31-Dec-19 HQ, U.S. Forces – Afghanistan / National Support Element Afghanistan 16-Dec-18 to 15-Nov-19 HQ, Combined Joint Task Force – Operation INHERENT RESOLVE 18-Sep-18 to 14-Sep-19 HQ, U.S. Central Command 1-Aug-18 to 31-Jul-20 HQ, Special Operations Joint Task Force – Afghanistan 4-Jun-18 to 3-Jun-19 Office of Security Cooperation – Iraq 1-Jan-18 to 31-Dec-18 HQ, U.S. Forces-Afghanistan / National Support Element Afghanistan 16-Nov-17 to 15-Dec-18 Office of the U.S. Security Coordinator for Israel and the Palestinian 2-Nov-17 to 30-Nov-18 Authority HQ, Military Information Support Task Force – Central 1-Oct-17 to 30-Sep-18 HQ, Combined Joint Task Force – Operation Inherent Resolve 6-Sep-17 to 17-Sep-18 HQ, Combined Joint Forces Land Component Command – Operation 31-Jul-17 to 23-Mar-18 INHERENT RESOLVE HQ, Joint Task Force 20 21-Jul-17 to 20-Oct-18 HQ, Special Operations Command Central 1-Jul-17 to 30-Jun-19 HQ, Special Operations Joint Task Force – Afghanistan 4-Jun-17 to 3-Jun-18 HQ, Combined Security Transition Command – Afghanistan / Deputy Chief 1-Jun-17 to 28-Nov-19 of Staff Security Assistance National Guard Bureau 1-Jun-17 to 1-Dec-18 HQ, Special Operations Joint Task Force – Operation INHERENT 18-May-17 to 31-Aug-18 RESOLVE HQ, Combined Joint Special Operations Air Component – Afghanistan 3-May-17 to 2-May-18 HQ, Combined Joint Task Force – Horn of Africa 1-Apr-17 to 30-Sep-18 HQ, U.S. -

Military Medical Ethics, Volume 2, Chapter 24, Military Medicine In

Military Medicine in Humanitarian Missions Chapter 24 MILITARY MEDICINE IN HUMANITARIAN MISSIONS JOAN T. ZAJTCHUK, MD, SPEC IN HSA* INTRODUCTION THE LEGAL AND MORAL BASIS FOR HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE THE BEGINNINGS OF US HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE (1900–1945) US HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE IN NATION BUILDING/ COUNTERINSURGENCY PROGRAMS (1945–1975) Nation Building After World War II The Emergence of Counterinsurgency Policies The Beginnings of Military Civic Action Doctrine Southeast Asia and Vietnam: Implementation of Civic Action Programs THE CHANGING CONCEPT OF NATION BUILDING (1975–2000) The Aftermath of the Vietnam War Nation Building in Central America: The Background The Beginning of the DoD Humanitarian Mission in Central America Formalizing the Role of the Department of Defense Honduras: Military Medicine in Civic Action Programs—The SOUTHCOM Model El Salvador: Military Medicine in Security Assistance Training Programs Project Coordination and Accountability THE IMPACT OF HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE IN CENTRAL AMERICA The Benefits of Humanitarian Assistance for Host Countries Some Problems Associated With Humanitarian Assistance THE PRESENT AND FUTURE OF NATION BUILDING (2001) CONCLUSION *Colonel (Retired), Medical Corps, United States Army; formerly, Consultant to the Army Surgeon General and the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs; Hospital Commander, Joint Task Force Bravo, Medical Element, Honduras and Command Surgeon, Honduras; currently, Professor of Otolaryngology and Bronchoesophagology, Center for Advanced Technology and International Health, Rush- Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Medical Center, 600 South Paulina, Suite 524, Chicago, Illinois 60612-3832 773 Military Medical Ethics, Volume 2 H. Charles McBarron Operation New Life Guam, 1975 Operation New Life occurred during the spring and summer of 1975. With the collapse of South Vietnam, more than 130,000 Southeast Asian refugees were evacuated to the United States. -

History of Us Army Special Operations in Panama

JULY - SEPTEMBER 2018 CONTENTS VOLUME 31 | ISSUE 3 ON THE COVER An element of the Panamanian ARTICLES Police marches during the Fuerzas Comando opening ceremony, July 06 | SOCSOUTH Overview and Map 16, 2018, at the Instituto Superior Policial, Panama. Fuerzas Comando 08 | In Depth: SOCOUTH Commander is an annual multinational special 12 | Regional Threat Overview: operations forces skills competition. Latin America and the Caribbean U.S. Army Photo by Staff Sgt. Brian Ragin 14 | Measuring Indirect Effects Over Time 18 | SOTF-77 30 52 22 | Integrated Campaigning 28 | Optimization of the Information and Influence Competencies 30 | The Last Line of Defense 36 | 5th SOF Truth 40 | A Team Effort 44 | The People Business 47 | Changing Culture 52 | SECTION: COLOMBIA 52 Colombia Overview 62 Protecting the Southern Approaches 68 Strategic Partnership 76 Enclaves in South America 80 ESMAI: The Future of Colobian PSYOP 84 | SECTION: EL SALVADOR 84 El Salvador Overview 92 MS-13's Stranglehold on a Nation 96 Evolution El Salvador 108 100 | SECTION: PANAMA 100 Panama Overview SUBSCRIBE 108 | Off the Range, Into the Jungle OFFICIAL DISTRIBUTION TO UNITS: Active Duty INDIVIDUALS: Personal 114 | Photostory: Fuerzas Comando and Reserve special operations units can subscribe subscriptions of Special to Special Warfare at no cost. Just email the following Warfare may be purchased information to [email protected] through the Government Printing office online at: DEPARTMENTS > Unit name / section https://bookstore.gpo.gov/ > Unit address FROM THE COMMANDANT ___ 04 products/ > Unit phone number sku/708-078-00000-0 FROM THE EDITOR _________ 05 > Quantity required SUBMISSIONS SPECIAL ARTICLE SUBMISSIONS: Special Warfare welcomes submissions of scholarly, independent research from members of the armed forces, security policy-makers and - shapers, defense analysts, academic specialists and civilians from the U.S.