Language Variations in the Botswana Speech Community and Its Impact on Children's Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title of Your Article

Vol. 11, No. 2 International Journal of Multicultural Education 2009 Monocultural Education in a Multicultural Society: The case of Teacher Preparation in Botswana Annah Anikie Molosiwa The University of Botswana Botswana In several policy documents reviewing the country’s education system, the Ministry of Education has made noteworthy pronouncements on how to improve teacher education in Botswana. This mainly concerns equipping teachers with pedagogical skills to better address the learning needs of the linguistically and culturally diverse student population. Even though at policy level it is acknowledged that Botswana is a multicultural society, at implementation stage there is no such evidence. This article argues that lack of implementation of policy pronouncements contradicts the government’s aspirations to provide equal learning opportunity to all learners. The infusion of courses in multicultural education at teacher education level is seen as an alternative. Introduction Geography and Language Description of Language Education Programs Literature Review Policy Pronouncements on Teacher Education Conclusion Notes References Introduction While the government of Botswana has made resources available to support the education of teachers, attempts to prepare teachers with the skills to better address the learning needs of the linguistically and culturally diverse student population in schools still remains inadequate. This contradicts the country‟s aspirations to provide equal educational opportunity to all citizens by the year 2016 (Republic of Botswana, 1997). The aim to increase access and equity at primary and secondary school levels and to improve the quality of education is pronounced in many policy documents such as the 1994 Revised National Policy on Education (RNPE) and Vision 2016 Report. -

Voicing on the Fringe: Towards an Analysis of ‘Quirkyʼ Phonology in Ju and Beyond

Voicing on the fringe: towards an analysis of ‘quirkyʼ phonology in Ju and beyond Lee J. Pratchett Abstract The binary voice contrast is a productive feature of the sound systems of Khoisan languages but is especially pervasive in Ju (Kx’a) and Taa (Tuu) in which it yields phonologically contrastive segments with phonetically complex gestures like click clusters. This paper investigates further the stability of these ‘quirky’ segments in the Ju language complex in light of new data from under-documented varieties spoken in Botswana that demonstrate an almost systematic devoicing of such segments, pointing to a sound change in progress in varieties that one might least expect. After outlining a multi-causal explanation of this phenomenon, the investigation shifts to a diachronic enquiry. In the spirit of Anthony Traill (2001), using the most recent knowledge on Khoisan languages, this paper seeks to unveil more on language history in the Kalahari Basin Area from these typologically and areally unique sounds. Keywords: Khoisan, historical linguistics, phonology, Ju, typology (AFRICaNa LINGUISTICa 24 (2018 100 Introduction A phonological voice distinction is common to more than two thirds of the world’s languages: whilst largely ubiquitous in African languages, a voice contrast is almost completely absent in the languages of Australia (Maddison 2013). The particularly pervasive voice dimension in Khoisan1 languages is especially interesting for two reasons. Firstly, the feature is productive even with articulatory complex combinations of clicks and other ejective consonants, gestures that, from a typological perspective, are incompatible with the realisation of voicing. Secondly, these phonological contrasts are robustly found in only two unrelated languages, Taa (Tuu) and Ju (Kx’a) (for a classification see Güldemann 2014). -

Identity and Plurilinguism in Africa – the Case of Mozambique

IDENTITY AND PLURILINGUISM IN AFRICA – THE CASE OF MOZAMBIQUE IDENTIDADE E PLURILINGUISMO NA ÁFRICA: O CASO DE MOÇAMBIQUE Sarita Monjane HENRIKSEN Universidade Pedagógica Mozambique International Abstract: The African continent is a true ethnic-linguistic and cultural mosaic, composed of 55 countries and characterised by the existence of approximately 2.000 languages and a large number of ethnic groups. Mozambique in the extreme south of the continent does not escape from this rule. The country, with its approximately 25 million inhabitants is characterised by a significantly high ethnic, linguistic and cultural diversity. In spite of this superdiversity it is possible to talk about an African identity and surely a Mozambican identity. The present study describes ethnic and cultural diversity in Africa, focusing on issues of plurilingualism or multilingualism in the continent. In addition, the study deals particularly with Mozambique’s ethnolinguistic landscape, discussing the importance of preserving diversity and lastly it presents a number of considerations on those factors that contribute to the construction of national identity and to the development of our Mozambicaness in this Indian Ocean country. Ke ywords: Identity, Plurilingualism, Ethnic-Linguistic and Cultural Diversity and Superdiversity Resumo: O continente africano é um verdadeiro mosaico étnico-linguístico e cultural, composto por 55 países e caracterizado pela existência de aproximadamente 2.000 línguas e inúmeros grupos étnicos. Moçambique no extremo sul deste continente não escapa a esta regra. O país, com os seus cerca de 25 milhões de habitantes é também caracterizado por uma significante diversidade étnica, linguística e cultural. Apesar desta superdiversidade é possível falar sobre uma identidade africana e uma identidade moçambicana. -

A Bottom-Up Approach to Language Education Policy in Mozambique Henriksen, Sarita Monjane

Roskilde University Language attitudes in a primary school a bottom-up approach to language education policy in Mozambique Henriksen, Sarita Monjane Publication date: 2010 Document Version Early version, also known as pre-print Citation for published version (APA): Henriksen, S. M. (2010). Language attitudes in a primary school: a bottom-up approach to language education policy in Mozambique. Roskilde Universitet. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain. • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 05. Oct. 2021 RRoosskkiillddee UUnniivveerrssiittyy DDeeppaarrttmmeenntt ooff CCuullttuurree aanndd IIddeennttiittyy Language Attitudes in a Primary School: A Bottom-Up Approach to Language Education Policy in Mozambique Sarita Monjane Henriksen 31-08-2010 LANGUAGE ATTITUDES IN A PRIMARY SCHOOL: A BOTTOM-UP APPROACH TO 31. august 2010 LANGUAGE EDUCATION POLICY IN MOZAMBIQUE RRoosskkiillddee UUnniivveerrssiittyy DDeeppaarrttmmeenntt ooff CCuullttuurree aanndd IIddeennttiittyy LLaanngguuaaggee AAttttiittuuddeess iinn aa PPrriimmaarryy SScchhooooll:: AA BBoottttoomm--UUpp AApppprrooaacchh ttoo LLaanngguuaaggee EEdduuccaattiioonn PPoolliiccyy iinn MMoozzaammbbiiqquuee SSaarriiitttaa MMoonnjjjaannee HHeennrriiikksseenn 2 LANGUAGE ATTITUDES IN A PRIMARY SCHOOL: A BOTTOM-UP APPROACH TO 31. -

The Marginalisation of Tonga in the Education System in Zimbabwe

THE MARGINALISATION OF TONGA IN THE EDUCATION SYSTEM IN ZIMBABWE BY PATRICK NGANDINI UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA NOVEMBER 2016 THE MARGINALISATION OF TONGA IN THE EDUCATION SYSTEM IN ZIMBABWE BY PATRICK NGANDINI Submitted in accordance with the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF LITERATURE AND PHILOSOPHY In the subject AFRICAN LANGUAGES at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA PROMOTER: Professor D. E. Mutasa Co – Promoter: Professor M. L. Mojapelo November 2016 Declaration STUDENT NUMBER: 53259955 I, Patrick Ngandini, declare that THE MARGINALISATION OF TONGA IN THE EDUCATION SYSTEM IN ZIMBABWE is my own work and that the sources I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. November 2016 Signature Date (PATRICK NGANDINI) i Dedication To my lovely wife Jesca Benza Ngandini, and my four children, Wadzanai Ashley, Rutendo Trish, Masimba and Wedzerai Faith. This thesis is also dedicated to my late father Simon Tsvetai Ngandini and my late mother Emilly Chamwada Maposa Ngandini who were my pillars throughout the painful process of my education. ii List of tables Table 2:1 Continental number of languages .......................................................................... 21 Table 2:2 Linguistic profile of Botswana............................................................................... 35 Table 4:2 Sample of the population ..................................................................................... 108 Table 5:1 Clauses from the Secretary‘s Circular No. 3 of 2002 .......................................... -

Globalization and the Myth of Killer Languages: What's Really Going

Salikoko S. Mufwene Globalization and the Myth of Killer Languages: What’s Really Going on? Introduction This paper is about some misgivings I harbor over some recent linguistics publications on language endangerment, i.e., the process whereby a language loses grounds to another either because it is spoken by fewer and fewer speakers and/or because it is heavily influenced by the competitor, which its speakers seem to command or like better. The targets of my criticisms include Crystal (2000, 2004), Dalby (2002), Nettle/Romaine (2000), Maffi (2001), Phillipson (2003), and Skutnabb-Kangas (2000), to whom I will often refer collectively, as they basically share the same positions, though there are minor differences in the specific ways they state them. Oversimplifying reality, they have generally reduced globalization to a process that makes the world more and more uniform by the world-wide diffusion of intellectual, linguistic, military, technological, and other cultural products associated with hegemonic regimes such as the USA, the United Kingdom, and Australia. In other words, they equate globalization with what would be the westernization of the world and talk about indigenous languages as if indigenity were no longer a relative notion and such languages were to be found only in the Americas, Asia, and Australia (Mufwene 2002). Capitalizing on the increasing attestations of Hollywood movies and McDonald restaurants around the world, they speak of McDonaldization and Americanization as if these phenomena either instantiated or produced globalization, whereas they should instead be treated as its (by-)products. To be sure, these authors are rightly concerned with growing political and economic power inequities (Stiglitz 2002, Steger 2003) that have been in favor of especially North America, Australia, Japan, and of Western Europe and have led to the endangerment or loss of several vernaculars not associated with their dominant, global economic systems. -

Multilingualism and Multiculturalism in the Education System and Society of Botswana

US-China Education Review B, August 2015, Vol. 5, No. 8, 488-502 doi:10.17265/2161-6248/2015.08.002 D DAVID PUBLISHING Multilingualism and Multiculturalism in the Education System and Society of Botswana Eureka Mokibelo University of Botswana, Gaborone, Botswana This study sought to examine how Botswana recognized and celebrated her linguistic and cultural diversity in society and in the education system. At various national celebrations, such as President’s Day, National Cultural Day, and National Language Day, Botswana celebrated her linguistic and cultural diversity by inviting ethnic groups from almost all regions of the society to perform cultural dances, poetry, and music while the same dispensation was denied primary school learners from ethnic minority groups. The use of Setswana as the medium of instruction leaves out the learners’ cultures, languages, and identities. Teachers and school management were the key participants in the study while learners’ artefacts were examined. Data were collected through open-ended questionnaires and interviews and analysis of documents/programmes from the Ministry of Sports, Youth and Culture responsible for national celebrations. The findings indicated that learners were denied linguistic and cultural diversity of their languages and cultures in the classrooms while there was evidence of celebrating culture and linguistic diversity in society. This called for a change in perspective and attitude to extend linguistic and cultural diversity to the classrooms so that learners could become capable of shouldering responsibility of their lives and participate in the development of their country. Keywords: multilingualism, multiculturalism, ethnic minority groups, national celebrations Introduction Even though most African countries are linguistically and culturally diverse, they lack a model of how to face such complexity in the classrooms. -

An Inclusive Linguistic Framework for Botswana: Reconciling the State and Perceived Marginalized Communities

Journal of Information, Information Technology, and Organizations Volume 5, 2010 An Inclusive Linguistic Framework for Botswana: Reconciling the State and Perceived Marginalized Communities K. C. Monaka and S. M. Mutula University of Botswana, Botswana [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract A people’s language and increasingly information communication technologies (ICTs) have emerged as powerful forces in enhancing political and socio-economic development. In Botswana there are several ethnic groups with diverse linguistic dialects. Each of the ethnic groups desires its dialect to be recognized by the state as official or national languages - integrated in education, media, and governance. The government recognizes only Setswana as the officialdom language and perceives agitation for multiple language use in officialdom as divisive and a threat to the long standing political and economic stability of the nation. This paper sought to examine Botswana’s perceived marginalized linguistic dialects by the state and proposes a linguistic framework for Botswana incorporating institutional and ICT aspects, which would appeal to both government and the ethnic groups concerned. The proposed linguistic framework for Botswana is applied as the methodological tool to examine the exclusion of the minority languages from the officialdom. The findings suggest that several ethnic groups in Bot- swana perceive their linguistic dialects as marginalised by the state. They seek the support of re- gional advocacy groups to help them promote their language values and culture, and they employ ICT to achieve their aims. However, the groups have not explored the existing international, re- gional, and national institutional frameworks to address their linguistic plight. -

Title San Cross-Border Cultural Heritage and Identity In

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository San Cross-border cultural heritage and identity in Botswana, Title Namibia and South Africa Author(s) BOLAANE, Maitseo Citation African Study Monographs (2014), 35(1): 41-64 Issue Date 2014-04 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/187748 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, 35(1): 41–64, April 2014 41 SAN CROSS-BORDER CULTURAL HERITAGE AND IDENTITY IN BOTSWANA, NAMIBIA AND SOUTH AFRICA Maitseo BOLAANE History Department, University of Botswana ABSTRACT The aim of this paper is to examine the indigenous San cultural identity that transcends ecological zones across the borders of Botswana, Namibia and South Africa respec- tively. The paper explores the representation of borders and boundaries within traditional cul- ture, dance and music. Dance, music, material art and craft, if broadly defined, become a me- dium through which San women and men narrate their experiences to a broader audience. The paper contends that giving voice to the San: in the many forms that such voice is captured, will significantly enhance our understanding of indigenous knowledge systems and thus better guide strategies towards transformation of modern southern African societies. The discussion aims to showcase San indigenous knowledge systems and creativity, and shift the discourse from a ‘marginalised and suffering only’ sphere to appreciation of their voices through culture, art, music and dance. The article suggests that the San artistic contribution, the articulation of their specific experiences and traditional knowledge enjoy significant attention across political boundaries. -

The Devastating Process of Identity Loss in Botswana

THE DEVASTATING PROCESS OF IDENTITY LOSS IN BOTSWANA Herman M. Batibo1 Abstract Many foreigners, who are not familiar with Botswana, assume that the country is monolingual, as they equate the name of the country with the main ethnic group, namely, Batswana. But Botswana is a typical multilingual country, with no less than 30 languages, most of which are highly diverse in form, structure and lexicon. This misconception of Botswana’s linguistic and cultural reality, both locally and internationally, has given rise to several devastating consequences. This article examines the devastating process of identity loss of the marginalized minority language groups of Botswana. The article identifies the main killer factors and proposes ways of alleviating the situation. The Lamy-Pool Identity Loss Model is evoked to determine the fate of the helpless languages. The study is based mainly on secondary data obtained from several sociolinguistic surveys carried out on the minority languages of Botswana. The findings of the study show the seriousness of ethnic identity loss and how it is affecting the whole country. Keywords: Multilingual, ethnic identity, language shift, exclusive language policy, negative attitudes, identity loss 1. Introduction Many foreigners, not familiar with Botswana, assume that the country is monolingual and mono-cultural, as they equate the name of the country, Botswana, with Batswana, the dominant ethnic group in the country. Because of historical and social reasons, this dominant ethnic group, constituting about 78.6% of the country’s population, has projected the image of this nation- state (Batibo et al., 2003). In fact, the term Batswana is used ambiguously to refer either to the ethnic group members or to all citizens of Botswana. -

A Critical Analysis of Namibia's English-Only Language Policy

A Critical Analysis of Namibia’s English-Only Language Policy Jenna Frydman University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1. Introduction When Namibia gained its political independence in 1990, it inherited a society characterized by segregation, vast urban and rural poverty, a highly skewed distribution of wealth, unequal access to land and natural resources, and dramatic inequalities in the quality of education and health services rendered to its various ethnic groups. The country was thus left at independence with a huge skills deficit and a slew of social imbalances to be resolved. In 2004, the Namibian government launched a national development strategy called Vision 2030 to address and resolve the country’s issues by the year 2030. The driving force behind the Vision was to be capacity building, aimed at operating a high quality education and training system, achieving full employment in the economy, and transforming Namibia into a knowledge-based society. Vision 2030 was further expected to reduce inequalities and create “a pervasive atmosphere of tolerance in matters relating to culture, religious practices, political preference, ethnic affiliation and differences in social background.” While this national development strategy is seemingly all-encompassing in the areas it set out to address and the issues it planned to resolve, it lacks entirely any mention of language or language policy. This absence in the plan is critical because language is not simply an area to be addressed or an issue to be resolved, but rather an issue that affects every other targeted area outlined in the plan. Namibia’s current language policy will, as will be argued in this paper, significantly impede progress in each of the areas that Vision 2030 has targeted. -

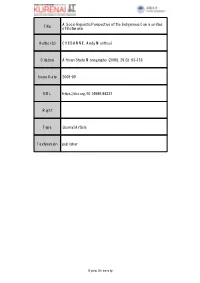

A Sociolinguistic Perspective of the Indigenous Communities Title of Botswana

A Sociolinguistic Perspective of the Indigenous Communities Title of Botswana Author(s) CHEBANNE, Andy Monthusi Citation African Study Monographs (2008), 29(3): 93-118 Issue Date 2008-09 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/66231 Right Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, 29(3): 93-118, September 2008 93 A SOCIOLINGUISTIC PERSPECTIVE OF THE INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES OF BOTSWANA Andy Monthusi CHEBANNE Faculty of Humanities, University of Botswana Visiting Fellow of the Graduate School of Asian and African Area Studies, Kyoto University, April – July, 2007 ABSTRACT The indigenous communities of Botswana discussed in this paper are gener- ally referred to as the Khoisan (Khoesan). While there are debates on the common origins of Khoisan communities, the existence of at least fi ve language families suggests a separate evolution that resulted in major grammatical and lexical differences between them. Due to historical confl icts with neighboring groups, they have been pushed far into the most inhos- pitable areas of the regions where they presently live. The most signifi cant victimization of Khoisan groups by the linguistic majority has been the systematic neglect of their languages and cultures. In fact, social and development programs have attempted to assimilate them into so-called majority ethnic groups and into modernity, and their languages have been dif- fi cult to conserve in contact situations. This paper provides an overview of these indigenous communities of Botswana and contributes to ongoing research of the region. I discuss rea- sons for the communities’ vulnerability by examining their demography, current localities, and language vitality. I also analyze some adverse effects of development and the danger the Khoisan face due to negative social and political attitudes, and formulate critical areas of in- tervention for the preservation of these indigenous languages.