Acadia National Park Colonial Waterbird Inventory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nahant Reconnaissance Report

NAHANT RECONNAISSANCE REPORT ESSEX COUNTY LANDSCAPE INVENTORY MASSACHUSETTS HERITAGE LANDSCAPE INVENTORY PROGRAM Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation Essex National Heritage Commission PROJECT TEAM Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation Jessica Rowcroft, Preservation Planner Division of Planning and Engineering Essex National Heritage Commission Bill Steelman, Director of Heritage Preservation Project Consultants Shary Page Berg Gretchen G. Schuler Virginia Adams, PAL Local Project Coordinator Linda Pivacek Local Heritage Landscape Participants Debbie Aliff John Benson Mark Cullinan Dan deStefano Priscilla Fitch Jonathan Gilman Tom LeBlanc Michael Manning Bill Pivacek Linda Pivacek Emily Potts Octavia Randolph Edith Richardson Calantha Sears Lynne Spencer Julie Stoller Robert Wilson Bernard Yadoff May 2005 INTRODUCTION Essex County is known for its unusually rich and varied landscapes, which are represented in each of its 34 municipalities. Heritage landscapes are those places that are created by human interaction with the natural environment. They are dynamic and evolving; they reflect the history of the community and provide a sense of place; they show the natural ecology that influenced the land use in a community; and heritage landscapes often have scenic qualities. This wealth of landscapes is central to each community’s character; yet heritage landscapes are vulnerable and ever changing. For this reason it is important to take the first steps toward their preservation by identifying those landscapes that are particularly valued by the community – a favorite local farm, a distinctive neighborhood or mill village, a unique natural feature, an inland river corridor or the rocky coast. To this end, the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) and the Essex National Heritage Commission (ENHC) have collaborated to bring the Heritage Landscape Inventory program (HLI) to communities in Essex County. -

Copyrighted Material

INDEX See also Accommodations and Restaurant indexes, below. GENERAL INDEX best, 9–10 AITO (Association of Blue Hill, 186–187 Independent Tour Brunswick and Bath, Operators), 48 AA (American Automobile A 138–139 Allagash River, 271 Association), 282 Camden, 166–170 Allagash Wilderness AARP, 46 Castine, 179–180 Waterway, 271 Abacus Gallery (Portland), 121 Deer Isle, 181–183 Allen & Walker Antiques Abbe Museum (Acadia Downeast coast, 249–255 (Portland), 122 National Park), 200 Freeport, 132–134 Alternative Market (Bar Abbe Museum (Bar Harbor), Grand Manan Island, Harbor), 220 217–218 280–281 Amaryllis Clothing Co. Acadia Bike & Canoe (Bar green-friendly, 49 (Portland), 122 Harbor), 202 Harpswell Peninsula, Amato’s (Portland), 111 Acadia Drive (St. Andrews), 141–142 American Airlines 275 The Kennebunks, 98–102 Vacations, 50 Acadia Mountain, 203 Kittery and the Yorks, American Automobile Asso- Acadia Mountain Guides, 203 81–82 ciation (AAA), 282 Acadia National Park, 5, 6, Monhegan Island, 153 American Express, 282 192, 194–216 Mount Desert Island, emergency number, 285 avoiding crowds in, 197 230–231 traveler’s checks, 43 biking, 192, 201–202 New Brunswick, 255 American Lighthouse carriage roads, 195 New Harbor, 150–151 Foundation, 25 driving tour, 199–201 Ogunquit, 87–91 American Revolution, 15–16 entry points and fees, 197 Portland, 107–110 America the Beautiful Access getting around, 196–197 Portsmouth (New Hamp- Pass, 45–46 guided tours, 197 shire), 261–263 America the Beautiful Senior hiking, 202–203 Rockland, 159–160 Pass, 46–47 nature -

Watchful Me. the Great State of Maine Lighthouses Maine Department of Economic Development

Maine State Library Digital Maine Economic and Community Development Economic and Community Development Documents 1-2-1970 Watchful Me. The Great State of Maine Lighthouses Maine Department of Economic Development Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalmaine.com/decd_docs Recommended Citation Maine Department of Economic Development, "Watchful Me. The Great State of Maine Lighthouses" (1970). Economic and Community Development Documents. 55. https://digitalmaine.com/decd_docs/55 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Economic and Community Development at Digital Maine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Economic and Community Development Documents by an authorized administrator of Digital Maine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. {conti11u( d lrom other sidt') DELIGHT IN ME . ... » d.~ 3~ ; ~~ HALF-WAY ROCK (1871], 76' \\:white granite towrr: dwPll ing. Submerged ledge halfway between Cape Small Point BUT DON'T DE-LIGHT ME. and Capp Elizabeth: Casco Bay. Those days are gone -- thP era of sail -- when our harbors d, · LITTLE MARK ISLAND MONUMENT (1927), 74' W: black and bays \\'ere filled with merchant and fishing ships powered atchful and white square pyramid. On bare islet. off S. Harpswell: by the wind. If our imagination sings to us that those vvere Casco Bay. days o! daring and adventure such reverie is not mistaken . PORTLAND LIGHTSHIP (1903], 65' W: red hull, "PORT Tho thP sailing ships arP few now, still with us are the LAND" on sides: circular gratings at mastheads. Off lighthousPs, shining into thP past e\'f~n while lighting the \vay Portland Harbor. for today's navigators aboard modern ships. -

National Register of Historic Places

NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES IN HANCOCK COUNTY, MAINE PLACE NAME STREET ADDRESS TOWN BRICK SCHOOL HOUSE SCHOOL HOUSE HILL AURORA TURRETS, THE EDEN STREET BAR HARBOR REDWOOD BARBERRY LANE BAR HARBOR HIGHSEAS SCHOONER HEAD ROAD BAR HARBOR CARRIAGE PATHS, BRIDGES AND GATEHOUSES ACADIA NATIONAL PARK+VICINITY BAR HARBOR EEGONOS 145 EDEN STREET BAR HARBOR CRITERION THEATRE 35 COTTAGE STREET BAR HARBOR WEST STREET HISTORIC DISTRICT WEST BET BILLINGS AVE+ EDEN ST BAR HARBOR SPROUL'S CAFE 128 MAIN STREET BAR HARBOR REVERIE COVE HARBORLANE BAR HARBOR ABBE, ROBERT, MUSEUM OF STONE AGE ANTIQUITY OFF ME 3 BAR HARBOR "NANAU" LOWER MAIN STREET BAR HARBOR JESUP MEMORIAL LIBRARY 34 MT DESERT ROAD BAR HARBOR KANE, JOHN INNES, COTTAGE OFF HANCOCK STREET BAR HARBOR US POST OFFICE - BAR HARBOR MAIN COTTAGE STREET BAR HARBOR SAINT SAVIOUR'S EPISCOPAL CHURCH & RECTORY 41 MT DESERT STREET BAR HARBOR COVER FARM OFF ME 3 (HULLS COVE) BAR HARBOR (FORMER) ST EDWARDS CONVENT 33 LEDGELAWN AVENUE BAR HARBOR HULLS COVE SCHOOL HOUSE CROOK ROAD & ROUTE 3 BAR HARBOR CHURCH OF OUR FATHER ME ROUTE 3 BAR HARBOR CLEFTSTONE 92 EDEN STREET BAR HARBOR STONE BARN FARM CROOKED RD AT NORWAY DRIVE BAR HARBOR FISHER, JONATHAN, MEMORIAL ME 15 (OUTER MAIN STREET) BLUE HILL HINCKLEY, WARD, HOUSE ADDRESS RESTRICTED BLUE HILL BARNCASTLE SOUTH STREET BLUE HILL BLUE HILL HISTORIC DISTRICT ME 15, ME 172, ME 176 & ME 177 BLUE HILL PETERS, JOHN, HOUSE OFF ME 176 BLUE HILL EAST BLUE HILL LIBRARY MILLIKEN ROAD BLUE HILL GODDARD SITE ADDRESS RESTRICTED BROOKLIN BROOKLIN IOOF HALL SR 175 -

Survey of Hancock County, Maine Samuel Wasson

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine History Documents Special Collections 1878 Survey of Hancock County, Maine Samuel Wasson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory Part of the United States History Commons Repository Citation Wasson, Samuel, "Survey of Hancock County, Maine" (1878). Maine History Documents. 37. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory/37 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History Documents by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SURVEY OF HANCOCK COUNTY. A SURVEY OF HANCOCK COUNTY, MAINE BY SAMIUEL WASSON. MEMBER OF STATE BOARD OK AGRICULTURE. AUGUSTA: SPRAGUE, OWEN A NASH, PRINTERS TO THE STATE. 1878. PREFACE. At the meeting of the Board of Agriculture held at Calais. a resolution was passed, urging the importance to our agri cultural literature of the publication of surveys of the differ ent counties in the State, giving brief notes of their history, industrial resources and agricultural capabilities ; and direct ing the Secretary to procure such contributions for the annual reports. In conformity with this resolution, and also as ear ning out the settled policy of the Board in this respect— evidences of which are found in the publication of similar reports in previous volumes—I give herewith a Survey of the County of Hancock, written by a gentleman who has been a member of the Board of Agriculture, uninterruptedly, from its first organization, and who is in every way well fitted for the work, which he has so well performed. -

Cranberry Isles Commuter Service Contact Information

Cranberry Isles Commuter Service Contact Information Provider: Town of Cranberry Isles Contact person: James Fortune, Denise McCormick Address: 61 Main Street, PO Box 56, Islesford, Maine 04646 Telephone: 207‐244‐4475 Email: james@cranberryisles‐me.gov, denise@cranberryisles‐me.gov Website: www.cranberryisles‐me.gov Service Summary Service area: Hancock County Type of service: Commuter ferry service Ferry Service The Cranberry Isles Commuter Service is one of three ferry services providing transportation from Great Cranberry Island and Islesford (Little Cranberry Island) to the mainland. It supplements the year‐ round service provided by the Beal and Bunker Mailboat which arrives at the islands and Northeast Harbor at different times, and the Cranberry Cove Ferry which runs a seasonal service to Manset and Southwest Harbor. While the Cranberry Isles Commuter Service is the only one partially supported by funds administered by Maine DOT, all three services form an integrated and coordinated system of transportation to and from the Town, so all three are described in the paragraphs below. Cranberry Isles Commuter Service. The Commuter Service operates five days per week, Monday through Friday. The Commuter Ferry allows islanders to arrive on the mainland earlier than they could otherwise by taking the Mailboat. Summer service (May 1 to October 14). During the summer, service is provided on the Elizabeth T, operated by Sail Acadia. The summer schedule is a morning trip only. The commuter ferry leaves Northeast Harbor at 6:00 a.m., picking up passengers on Great Cranberry and leaving about 6:15 a.m., then picking up passengers on Islesford and leaving about 6:30 a.m. -

East Point History Text from Uniguide Audiotour

East Point History Text from UniGuide audiotour Last updated October 14, 2017 This is an official self-guided and streamable audio tour of East Point, Nahant. It highlights the natural, cultural, and military history of the site, as well as current research and education happening at Northeastern University’s Marine Science Center. Content was developed by the Northeastern University Marine Science Center with input from the Nahant Historical Society and Nahant SWIM Inc., as well as Nahant residents Gerry Butler and Linda Pivacek. 1. Stop 1 Welcome to East Point and the Northeastern University Marine Science Center. This site, which also includes property owned and managed by the Town of Nahant, boasts rich cultural and natural histories. We hope you will enjoy the tour Settlement in the Nahant area began about 10,000 years ago during the Paleo-Indian era. In 1614, the English explorer Captain John Smith reported: the “Mattahunts, two pleasant Iles of grouse, gardens and corn fields a league in the Sea from the Mayne.” Poquanum, a Sachem of Nahant, “sold” the island several times, beginning in 1630 with Thomas Dexter, now immortalized on the town seal. The geography of East Point includes one of the best examples of rocky intertidal habitat in the southern Gulf of Maine, and very likely the most-studied as well. This site is comprised of rocky headlands and lower areas that become exposed between high tide and low tide. This zone is easily identified by the many pools of seawater left behind as the water level drops during low tide. The unique conditions in these tidepools, and the prolific diversity of living organisms found there, are part of what interests scientists, as well as how this ecosystem will respond to warming and rising seas resulting from climate change. -

2016 Minutes

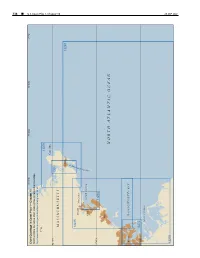

Gulf of Maine Seabird Working Group nd 32 Annual Summer Meeting Hog Island, Bremen, Maine August 12, 2016 Visit the website gomswg.org 1 Table of Contents Seabird Islands – Gulf of Maine (map).............................................................................................3 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................4 Island and Site Reports .....................................................................................................................4 Canada.................................................................................................................................4 Country Island.......................................................................................................4 North Brother Island..............................................................................................6 Machias Seal Island ..............................................................................................8 Maine ..................................................................................................................................10 Eastern Brothers ...................................................................................................10 Petit Manan Island ..............................................................................................................13 Ship Island ..........................................................................................................................16 -

Little Cranberry Island in 1870 and the 1880S

National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places U.S. Department of the Interior Life on an Island: Early Settlers off the Rock-Bound Coast of Maine Life on an Island: Early Settlers off the Rock-Bound Coast of Maine (Islesford Historical Museum, 1969, Acadia National Park) (The Blue Duck, 1916, Acadia National Park) Off the jagged, rocky coast of Maine lie approximately 5,000 islands ranging in size from ledge outcroppings to the 80,000 acre Mount Desert Island. During the mid-18th century many of these islands began to be inhabited by settlers eager to take advantage of this interface between land and sea. National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places U.S. Department of the Interior Life on an Island: Early Settlers off the Rock-Bound Coast of Maine Living on an island was not easy, however. The granite islands have a very thin layer of topsoil that is usually highly acidic due to the spruce forests dominating the coastal vegetation. Weather conditions are harsh. Summers are often cool with periods of fog and rain, and winters--although milder along the coast than inland--bring pounding storms with 60-mile-per-hour winds and waves 20 to 25 feet high. Since all trading, freight- shipping, and transportation was by water, such conditions could isolate islanders for long periods of time. On a calm day, the two-and-one-half-mile boat trip from Mount Desert Island to Little Cranberry Island takes approximately 20 minutes. As the boat winds through the fishing boats in the protected harbor and approaches the dock, two buildings command the eye's attention. -

A Range and Distribution Study of the Natural European Oyster, Ostrea Edulis, Population in Casco Bay, Maine

A RANGE AND DISTRIBUTION STUDY OF THE NATURAL EUROPEAN OYSTER, OSTREA EDULIS, POPULATION IN CASCO BAY, MAINE By C.S. HEINIG and B.P. TARBOX INTERTIDE CORPORATION SOUTH HARPSWELL, MAINE 04079 1985 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT We wish to thank Dana Wallace, recently retired from the Department of Marine Resources, for his assistance in the field and his insight. We also wish to thank Walter Welsh and Laurice Churchill of the Department of Marine Resources for their help with background information and data. Thanks also go to Peter Darling, Cook's Lobster, Foster Treworgy, Interstate Lobster, Robert Bibber and Dain and Henry Allen for allowing us the use of their wharfs, docks, and moorings. Funding for this project was provided by the State Department of Marine Resources with equipment and facilities provided by INTERTIDE CORPORATION. TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT..................................................................................................................................... i INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 METHODS AND MATERIALS.................................................................................................... 2 DATA AND OBSERVATIONS .................................................................................................... 3 A. Geographic Range and Distribution...................................................................................... 3 Section 1. Cape Small to Harbor Island, New Meadows River............................................ -

CPB1 C10 WEB.Pdf

338 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 1, Chapter 10 Chapter 1, Pilot Coast U.S. 70°45'W 70°30'W 70°15'W 71°W Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 1—Chapter 10 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 71°W 13279 Cape Ann 42°40'N 13281 MASSACHUSETTS Gloucester 13267 R O B R A 13275 H Beverly R Manchester E T S E C SALEM SOUND U O Salem L G 42°30'N 13276 Lynn NORTH ATLANTIC OCEAN Boston MASSACHUSETTS BAY 42°20'N 13272 BOSTON HARBOR 26 SEP2021 13270 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 1, Chapter 10 ¢ 339 Cape Ann to Boston Harbor, Massachusetts (1) This chapter describes the Massachusetts coast along and 234 miles from New York. The entrance is marked on the northwestern shore of Massachusetts Bay from Cape its eastern side by Eastern Point Light. There is an outer Ann southwestward to but not including Boston Harbor. and inner harbor, the former having depths generally of The harbors of Gloucester, Manchester, Beverly, Salem, 18 to 52 feet and the latter, depths of 15 to 24 feet. Marblehead, Swampscott and Lynn are discussed as are (11) Gloucester Inner Harbor limits begin at a line most of the islands and dangers off the entrances to these between Black Rock Danger Daybeacon and Fort Point. harbors. (12) Gloucester is a city of great historical interest, the (2) first permanent settlement having been established in COLREGS Demarcation Lines 1623. The city limits cover the greater part of Cape Ann (3) The lines established for this part of the coast are and part of the mainland as far west as Magnolia Harbor. -

2016 GOMSWG Census Data Table

2016 Gulf of Maine Seabird Working Group Census Results Census Window: June 12-22 (peak of tern incubation) (Results from region-wide count period are reported here - refer to island synopsis or contact island staff for season totals) *not located in the Gulf of Maine or included in GOM totals numbers need to be verified ISLAND NAME DATE METHOD COTE ARTE ROST LETE LAGU FLEDGE/NEST N SD METHOD EGGS/NEST N SD OBSERVER NOVA SCOTIA 6/12 N 619 Julie McKnight North Brother 6/12 N 35 Julie McKnight South Brother Grassy Island 6/17 - 6/20 N 893 1.23 39 0.20 1, 3 Jen Rock Country Island (not in GOM) 6/17 - 6/20 N 581 1.18 28 0.22 1, 3 Jen Rock Season Total N 18 1.60 5 0.22 3 Jen Rock 2016 NS COAST TOTAL 619 50 2015 NS COAST TOTAL 687 0 35 0 0 2014 NS COAST TOTAL 651 44 38 0 0 2013 NS COAST TOTAL 596 50 38 0 0 2012 NS COAST TOTAL 574 50 34 0 0 2011 NS COAST TOTAL 631 60 38 0 0 2010 NS COAST TOTAL 632 54 38 0 0 * Data for The Brothers is reported as total count, with 38 roseates. 2009 NS COAST TOTAL 473 42 42 0 0 2008 NS COAST TOTAL 527 28 55 0 0 NEW BRUNSWICK ISLAND NAME DATE METHOD COTE ARTE ROST LETE LAGU FLEDGE/NEST N SD METHOD EGGS/NEST N SD OBSERVER Machias Seal Season Total NP 175 0.55 (ARTE only) 54 (ARTE only) 2,3 1.52 (ARTE only)4 (ARTE on 0.60 Stefanie Collar 2016 NB COAST TOTAL A tern census was not conducted this year, but it is estimated that there were up to 175 attempted nests island-wide, with a 2015 NB COAST TOTAL 9 141 0 0 0 probable species distribution of 94% ARTE and 6% COTE, similar to last year.