Sustainable Livelihoods Analysis Dessie Zuria, Wollo Zone of Amhara Region June 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti

Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti DISSERTATION ZUR ERLANGUNG DER GRADES DES DOKTORS DER PHILOSOPHIE DER UNIVERSTÄT HAMBURG VORGELEGT VON YASIN MOHAMMED YASIN from Assab, Ethiopia HAMBURG 2010 ii Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti by Yasin Mohammed Yasin Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULITY OF BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES at the UNIVERSITY OF HAMBURG Supervisors Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff HAMBURG 15 December 2010 iii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral fathers Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit and Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff for their critical comments and kindly encouragement that made it possible for me to complete this PhD project. Particularly, Prof. Jakobeit’s invaluable assistance whenever I needed and his academic follow-up enabled me to carry out the work successfully. I therefore ask Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit to accept my sincere thanks. I am also grateful to Prof. Dr. Klaus Mummenhoff and the association, Verein zur Förderung äthiopischer Schüler und Studenten e. V., Osnabruck , for the enthusiastic morale and financial support offered to me in my stay in Hamburg as well as during routine travels between Addis and Hamburg. I also owe much to Dr. Wolbert Smidt for his friendly and academic guidance throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. Special thanks are reserved to the Department of Social Sciences at the University of Hamburg and the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) that provided me comfortable environment during my research work in Hamburg. -

British Geological Survey PLANNING

British Geological Survey TECHNICAL REPORT WC/00/13 Overseas Geology Series PLANNING FOR GROUNDWATER DROUGHT IN AFRICA: TOWARDS A SYSTEMATIC APPROACH FOR ASSESSING WATER SECURITY IN ETHIOPIA Project report on visit to Ethiopia, November-December 1999 British Geological Survey, Wallingford British Geological Survey TECHNICAL REPORT WC/00/13 Overseas Geology Series PLANNING FOR GROUNDWATER DROUGHT IN AFRICA: TOWARDS A SYSTEMATIC APPROACH FOR ASSESSING WATER SECURITY IN ETHIOPIA Project report on visit to Ethiopia, November-December 1999 R C Calow1, A M MacDonald1 and A L Nicol2 1British Geological Survey 2Overseas Development Institute This document is an output from a project funded by the Department for International Development (DFID) for the benefit of developing countries. The views expressed are not necessarily those of the DFID. DFID classification: Subsector: Water and Sanitation Theme: W4 – Raise the well-being of the rural and urban poor through cost-effective improved water supply and sanitation Project Title: Groundwater drought early warning for vulnerable areas Project reference: R7125 Bibliographic reference: Calow, R C, MacDonald, A M and Nicol, A L 2000. Planning for Groundwater Drought in Africa. Towards a Systematic Approach for Assessing Water Security in Ethiopia. Project report on visit to Ethiopia, November – December 1999 BGS Technical Report WC/00/13 Keywords:Ethiopia, groundwater, drought, monitoring Front cover illustration: Looking down onto the River Mille from Abbot Village, Ambassel Woreda. © NERC 2000 Keyworth, Nottingham, British Geological Survey, 2000 Contents Executive Summary iv 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Visit Objectives 1 1.2 Visit Background 1 1.3 Project Aims and Outputs 3 2. THE STUDY AREA: SOUTH WOLLO 4 2.1 Selection Criteria 4 2.2 Physical Background 5 2.3 Socio-economic Background 5 2.4 Institutions 6 3. -

ETHIOPIA - National Hot Spot Map 31 May 2010

ETHIOPIA - National Hot Spot Map 31 May 2010 R Legend Eritrea E Tigray R egion !ª D 450 ho uses burned do wn d ue to th e re ce nt International Boundary !ª !ª Ahferom Sudan Tahtay Erob fire incid ent in Keft a hum era woreda. I nhabitan ts Laelay Ahferom !ª Regional Boundary > Mereb Leke " !ª S are repo rted to be lef t out o f sh elter; UNI CEF !ª Adiyabo Adiyabo Gulomekeda W W W 7 Dalul E !Ò Laelay togethe r w ith the regiona l g ove rnm ent is Zonal Boundary North Western A Kafta Humera Maychew Eastern !ª sup portin g the victim s with provision o f wate r Measle Cas es Woreda Boundary Central and oth er imm ediate n eeds Measles co ntinues to b e re ported > Western Berahle with new four cases in Arada Zone 2 Lakes WBN BN Tsel emt !A !ª A! Sub-city,Ad dis Ababa ; and one Addi Arekay> W b Afa r Region N b Afdera Military Operation BeyedaB Ab Ala ! case in Ahfe rom woreda, Tig ray > > bb The re a re d isplaced pe ople from fo ur A Debark > > b o N W b B N Abergele Erebtoi B N W Southern keb eles of Mille and also five kebeles B N Janam ora Moegale Bidu Dabat Wag HiomraW B of Da llol woreda s (400 0 persons) a ff ected Hot Spot Areas AWD C ases N N N > N > B B W Sahl a B W > B N W Raya A zebo due to flo oding from Awash rive r an d ru n Since t he beg in nin g of th e year, Wegera B N No Data/No Humanitarian Concern > Ziquala Sekota B a total of 967 cases of AWD w ith East bb BN > Teru > off fro m Tigray highlands, respective ly. -

Starving Tigray

Starving Tigray How Armed Conflict and Mass Atrocities Have Destroyed an Ethiopian Region’s Economy and Food System and Are Threatening Famine Foreword by Helen Clark April 6, 2021 ABOUT The World Peace Foundation, an operating foundation affiliated solely with the Fletcher School at Tufts University, aims to provide intellectual leadership on issues of peace, justice and security. We believe that innovative research and teaching are critical to the challenges of making peace around the world, and should go hand-in- hand with advocacy and practical engagement with the toughest issues. To respond to organized violence today, we not only need new instruments and tools—we need a new vision of peace. Our challenge is to reinvent peace. This report has benefited from the research, analysis and review of a number of individuals, most of whom preferred to remain anonymous. For that reason, we are attributing authorship solely to the World Peace Foundation. World Peace Foundation at the Fletcher School Tufts University 169 Holland Street, Suite 209 Somerville, MA 02144 ph: (617) 627-2255 worldpeacefoundation.org © 2021 by the World Peace Foundation. All rights reserved. Cover photo: A Tigrayan child at the refugee registration center near Kassala, Sudan Starving Tigray | I FOREWORD The calamitous humanitarian dimensions of the conflict in Tigray are becoming painfully clear. The international community must respond quickly and effectively now to save many hundreds of thou- sands of lives. The human tragedy which has unfolded in Tigray is a man-made disaster. Reports of mass atrocities there are heart breaking, as are those of starvation crimes. -

Yes I Do. Ethiopia – Amhara Region

Yes I Do. Ethiopia – Amhara Region The situation of child marriage in Qewet and Bahir Dar Zurida: a focus on gender roles, parenting and young people’s future perspectives Abeje Berhanu Dereje Tesama Beleyne Worku Almaz Mekonnen Lisa Juanola Anke van der Kwaak University of Addis Ababa & Royal Tropical Institute January 2019 1 Contents Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................................ 3 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Background of the Yes I Do programme .............................................................................................. 4 1.2 Process of identifying themes for this study ....................................................................................... 4 1.3 Social and gender norms related to child marrige .............................................................................. 5 1.4 Objective of the study ......................................................................................................................... 7 2. Methodology ......................................................................................................................................... 9 2.1 Description of the study areas ............................................................................................................. 9 2.1.1 Qewet woreda, North Shewa zone.............................................................................................. -

Accessibility Inequality to Basic Education in Amhara Region

Accessibility in equality to Basic Education O.A. A. & Kerebih A. 11 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Accessibility In equality to Basic Education in Amhara Region, Ethiopia. O.A. AJALA (Ph.D.) * Kerebih Asres** ABSTRACT Accessibility to basic educational attainment has been identified as collateral for economic development in the 21st century. It has a fundamental role in moving Africa countries out of its present tragic state of underdevelopment. This article examines the situation of basic educational services in Amhara region of Ethiopia in terms of availability and accessibility at both primary and secondary levels. It revealed that there is a gross inadequacy in the provision of facilities and personnel to adequately prepare the youth for their future, in Amhara region. It also revealed the inequality of accessibility to basic education services among the eleven administrative zones in the region with antecedent impact on the development levels among the zones and the region at large. It thus called for serious intervention in the education sector of the region, if the goal of education for development is to be realized, not only in the region but in the country at large.. KEYWORDS: Accessibility, Basic Education, Development, Inequality, Amhara, Ethiopia _________________________________________________________________ Dept. of Geography Bahir Dar University Bahir Dar, Ethiopia * [email protected] Ethiop. J. Educ. & Sc. Vol. 3 No. 2 March, 2008 12 INTRODUCTION of assessment of educational services provision at primary and secondary schools Accessibility to basic education has been in Ethiopia, taking Amhara National identified as a major indicator of human Regional State as a case study. capital formation of a country or region, which is an important determinant of its The article is arranged into six sections. -

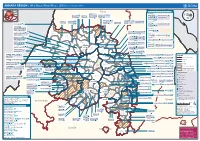

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (As of 13 February 2013)

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (as of 13 February 2013) Tigray Tigray Interventions/Projects at Woreda Level Afar Amhara ERCS: Lay Gayint: Beneshangul Gumu / Dire Dawa Plan Int.: Addis Ababa Hareri Save the fk Save the Save the df d/k/ CARE:f k Save the Children:f Gambela Save the Oromia Children: Children:f Children: Somali FHI: Welthungerhilfe: SNNPR j j Children:l lf/k / Oxfam GB:af ACF: ACF: Save the Save the af/k af/k Save the df Save the Save the Tach Gayint: Children:f Children: Children:fj Children:l Children: l FHI:l/k MSF Holand:f/ ! kj CARE: k Save the Children:f ! FHI:lf/k Oxfam GB: a Tselemt Save the Childrenf: j Addi Dessie Zuria: WVE: Arekay dlfk Tsegede ! Beyeda Concern:î l/ Mirab ! Concern:/ Welthungerhilfe:k Save the Children: Armacho f/k Debark Save the Children:fj Kelela: Welthungerhilfe: ! / Tach Abergele CRS: ak Save the Children:fj ! Armacho ! FHI: Save the l/k Save thef Dabat Janamora Legambo: Children:dfkj Children: ! Plan Int.:d/ j WVE: Concern: GOAL: Save the Children: dlfk Sahla k/ a / f ! ! Save the ! Lay Metema North Ziquala Children:fkj Armacho Wegera ACF: Save the Children: Tenta: ! k f Gonder ! Wag WVE: Plan Int.: / Concern: Save the dlfk Himra d k/ a WVE: ! Children: f Sekota GOAL: dlf Save the Children: Concern: Save the / ! Save: f/k Chilga ! a/ j East Children:f West ! Belesa FHI:l Save the Children:/ /k ! Gonder Belesa Dehana ! CRS: Welthungerhilfe:/ Dembia Zuria ! î Save thedf Gaz GOAL: Children: Quara ! / j CARE: WVE: Gibla ! l ! Save the Children: Welthungerhilfe: k d k/ Takusa dlfj k -

The Case of Dessie Zuria Woreda

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1700 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2855 (Online) DOI: 10.7176/JESD Vol.10, No.5, 2019 Determinants of Households Saving Capacity and Bank Account Holding Experience in Ethiopia: The Case of Dessie Zuria Woreda Bazezew Endalew College of Business and Economics, Department of Economics, Wollo University, Dessie, Ethiopia Abstract This research has been an attempt to identify the major determinants that affect households saving capacity and their experience of adopting formal financial institutions (banks) in the case of Dessie Zuria Woreda. To do so, an individual base cross-sectional data analysis along with the two stage sampling technique of both purposive and random sampling technique was undertaken. To analyze the data, the study employed two sets of models (logistic and the method of principal component analysis). The econometric results of the study indicates that determinants like lack of credit access, lack of financial planning, complexity of banking system, monthly expenditure on stimulants, sex, significantly and negatively affects households saving capacity, but monthly income, age, bank account holding experience, marital status, and occupation positively and significantly affects saving capacity. In similar fashion, determinants include improper government policy, weak institutional set up, complexity of banking system, distance in Km away from their home to financial institutions, and religion significantly and negatively affect the probability of households to be banked, on the other hand, sex of households, credit access, income, marital status, education and age positively and significantly affects the probability of households to be banked. -

Transhumance Cattle Production System in North Gondar, Amhara Region, Ethiopia: Is It Sustainable?

WP14_Cover.pdf 2/12/2009 2:21:51 PM www.ipms-ethiopia.org Working Paper No. 14 Transhumance cattle production system in North Gondar, Amhara Region, Ethiopia: Is it sustainable? C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Transhumance cattle production system in North Gondar, Amhara Region, Ethiopia: Is it sustainable? Azage Tegegne,* Tesfaye Mengistie, Tesfaye Desalew, Worku Teka and Eshete Dejen Improving Productivity and Market Success (IPMS) of Ethiopian Farmers Project, International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia * Corresponding author: [email protected] Authors’ affiliations Azage Tegegne, Improving Productivity and Market Success (IPMS) of Ethiopian Farmers Project, International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Tesfaye Mengistie, Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Development, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia Tesfaye Desalew, Kutaber woreda Office of Agriculture and Rural Development, Kutaber, South Wello Zone, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia Worku Teka, Research and Development Officer, Metema, Amhara Region, Improving Productivity and Market Success (IPMS) of Ethiopian Farmers Project, International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Eshete Dejen, Amhara Regional Agricultural Research Institute (ARARI), P.O. Box 527, Bahir Dar, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia © 2009 ILRI (International Livestock Research Institute). All rights reserved. Parts of this publication may be reproduced for non-commercial use provided that such reproduction shall be subject to acknowledgement of ILRI as holder of copyright. Editing, design and layout—ILRI Publications Unit, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Correct citation: Azage Tegegne, Tesfaye Mengistie, Tesfaye Desalew, Worku Teka and Eshete Dejen. 2009. Transhumance cattle production system in North Gondar, Amhara Region, Ethiopia: Is it sustainable? IPMS (Improving Productivity and Market Success) of Ethiopian Farmers Project. -

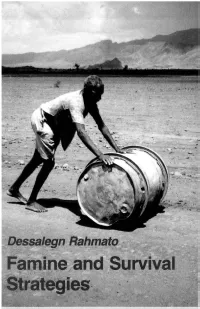

Famine and Survival Strategies Famine and Survival Strategies

Famine and Survival Strategies Famine and Survival Strategies A Case Study from Northeast Ethiopia Dessalegn Rahmato Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, Uppsala 199 1 (The Scandinavian Institute of African Studies) This book is published with support from The Swedish International Development Authority (SIDA) ISBN 91-7106-314-5 O Dessalegn Rahmato and Nordiska Afrikainstitutet 1991 Typeset and printed in Sweden by Bohuslaningens Boktryckeri AB, Uddevalla 199 1 Contents Abbreviations 6 Glossary 7 Acknowledgements 9 Section I INTRODUCTION 1. Objectives of the Study 13 Community and the ethic of cooperation 18 2. Organization of the Study 35 Sources for the Study 36 Technical problems and usage 43 Section I1 FAMINE: HIDING BEHIND THE MOUNTAINS 3. Wollo and Ambassel: The Setting 47 4. The Economy of Wollo 57 5. The Peasant Mode of Production 69 Farming practices 76 The control of the micro-environment 81 Consumption, marketing and prices 87 6. Famine in Wollo 99 The death toll (1984-85) 107 Section 111 SURVIVAL: COMMUNITY AND COOPERATION 7. The Community in Distress 117 Crisis anticipation 118 Magic and divination 125 Crisis management 141 Exhaustion and dispersal 156 8. Survival Strategies 163 Austerity and reduced consumption 165 Divestment and asset disposal 171 Livestock flows during the famine 176 Normal and abnormal behaviour 182 9. Post Famine Recovery 193 Section IV BEYOND SURVIVAL 10. Neither Feast Nor Famine 21 1 Disaster designation and early warning 219 References 227 Information from Official Records 227 Primary Sources 227 Secondary Sources 230 Annexes 1. Rainfall Data, Haiq Station, Ambassel 1963-1984 2. Livestock Supply and Prices, Haiq Market 3. Grain Prices, Bistima Market, Ambassel 4. -

The Ethiopia-Eritrea Rapprochement : Peace and Stability in the Horn Of

ETHIOPIA–ERITREA RAPPROCHEMENT: RAPPROCHEMENT: ETHIOPIA–ERITREA THE RECENT RAPPROCHEMENT between Ethiopia and Eritrea has fundamentally reshaped the relation- ship between the two countries. The impact of the resolution of the Ethiopia-Eritrea conflict goes beyond the borders of the two countries, and has indeed AFRICA THE HORN OF IN AND STABILITY PEACE brought fundamental change to the region. Full diplo- The Ethiopia-Eritrea matic relations have been restored between Eritrea and Peace and Stability Somalia; and the leaders of Eritrea and Djibouti have met in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. The central question the Rapprochement in the Horn of Africa book attempts to address is: what factors led to the resolution of a festering conflict? The book explains and analyses the rapprochement, which it argues was made possible by the maturing of objective and sub- jective conditions in Ethiopia and by the trust factor in Eritrea. REDIE BEREKETEAB is a Senior Researcher and Associate Professor in Sociology at the Nordic Africa Institute in Uppsala, Sweden. His main field of research is conflict and state building in the Horn of Africa, and the regional economic communities (RECs) and peace building in Africa. REDIE BEREKETEAB ISBN 9789171068491 90000 > Policy Dialogue No. 13 Redie Bereketeab 9 789171 068491 POLICY DIALOGUE No. 13 THE ETHIOPIA-ERITREA RAPPROCHEMENT Peace and Stability in the Horn of Africa Author Redie Bereketeab NORDISKA AFRIKAINSITUTET The Nordic Africa Institute UPPSALA 2019 INDEXING TERMS: Ethiopia Eritrea Foreign relations Regional cooperation Regional integration Dispute settlement Political development Peacebuilding Reconciliation The Ethiopia-Eritrea Rapprochement: Peace and Stability in the Horn of Africa Author: Redie Bereketeab ISBN 978-91-7106-849-1 print ISBN 978-91-7106-850-7 pdf © 2019 The author and the Nordic Africa Institute Layout: Henrik Alfredsson, The Nordic Africa Institute and Marianne Engblom, Ateljé Idé. -

Heading with Word in Woodblock

Amhara Region, Area brief Regional Overview The Amhara Region is located in the northwestern part of Ethiopia; its land area is estimated at about 170,000 square kilometers. Amhara borders Tigray Region in the North, Afar in the East, Oromiya in the South, Benishangul-Gumuz in the Southwest and the country of Sudan in the west. Based on the 2007 figures from the Central Statistical Agency (CSA) of Ethiopia, Amhara has an estimated total population of 20,136,000. 88% of the population is estimated to be rural inhabitants, while 12% are urban dwellers. Bahir-Dar is the capital city of the Amhara Regional State. Amhara is divided into 11 zones, and 167 woredas (districts). There are about 3,429 kebeles (the smallest administrative units). Decision-making power has been decentralized to woredas and thus the woredas are responsible for all development activities in their areas. The historic Amhara region contains much of the highland plateaus above 1,500 meters with rugged formations, gorges and valleys, as well as millions of settlements for Amhara villages surrounded by subsistence farms and grazing fields. Located in this region are the world-renowned Blue Nile River and its source, Lake Tana, as well as historic sites including Gonder palace, and the Lalibela rock-hewn churches. The land in Amhara has been cultivated for millennia with no variations or improvement in the farming techniques. The resulting environmental damage has contributed to the trend of deteriorating climate with frequent droughts, loss of crops and the resulting food shortage. Of the 167 woredas in the region, fifty-eight (35%) are drought-prone and chronically food- insecure.