The Violet Quill Club: Constructing a Post-Stonewall Gay Identity Through Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GED Creative Writing Class

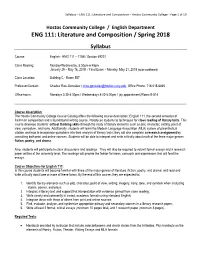

Syllabus – ENG 111: Literature and Composition – Hostos Community College - Page 1 of 10 Hostos Community College / English Department ENG 111: Literature and Composition / Spring 2018 Syllabus Course: English - ENG 111 – 715B / Section 49207 Class Meeting: Monday/Wednesday, 5:30pm-6:45pm January 29 – May 16, 2018 / Final Exam – Monday, May 21, 2018 (to be confirmed) Class Location: Building C - Room 557 Professor/Contact: Charles Rice-González | [email protected]; Office Phone: 718-518-6865 Office hours: Mondays 3:30-4:30pm / Wednesdays 4:00-5:00pm / (by appointment)/Room B-514 Course description: The Hostos Community College Course Catalog offers the following course description: English 111, the second semester of freshman composition and a foundational writing course, introduces students to techniques for close reading of literary texts. This course develops students’ critical thinking skills through the study of literary elements such as plot, character, setting, point of view, symbolism, and irony. Additionally, students will learn the Modern Language Association (MLA) system of parenthetical citation and how to incorporate quotations into their analysis of literary texts; they will also complete a research assignment by consulting both print and online sources. Students will be able to interpret and write critically about each of the three major genres: fiction, poetry, and drama. Also, students will participate in class discussions and readings. They will also be required to submit formal essays and a research paper written at the university level. The readings will provide the fodder for ideas, concepts and experiences that will feed the essays. Course Objectives for English 111: In this course students will become familiar with three of the major genres of literature (fiction, poetry, and drama) and read and write critically about one or more of these forms. -

Felice Picano Eric Andrews-Katz

Our History Felice Picano Eric Andrews-Katz Felice Picano is one of the premier forces of the American years. I met Edmund White in Greenwich Village in 1976, gay literary movement. He has authored over twenty-five and George Whitmore in ’77. Chris Cox was Edmund’s books of fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and plays. Nominated boyfriend; George and I were tempestuous boyfriends at for four Lambda Literary Awards and a finalist for the the time, but he was instrumental in forming the group. PEN Foundation/Hemingway Award, Picano has won Robert was also very socially active, so he and George the Syndicated Fiction/PEN Award, the Ferro-Grumley pulled it together. Award, and the Gay Times of England Award for best gay novel and best short story. Several of Picano’s novels ERIC: Do you find advantages with using a writer’s have been reissued by Bold Strokes Books, and his latest group? memoir, True Stories: Portraits of My Past, has garnered some of the best reviews of his career. Picano, now in his FELICE: We did then because nobody was taking our mid-sixties, continues to write new stories and publish writing seriously, and neither were our friends. No one new work. This fall Bold Strokes is releasing his third would have anything to do with gay literature. They all collection of short fiction,Contemporary Gay Romances, said, “There’s no such thing; there’s only porn.” We had to and next year will publish a fourth collection, Twelve find each other, little by little, and then write and define O’Clock Tales, comprised of the author’s genre, mystery, what was both “gay” and “literature” at the same time; and speculative fiction stories. -

Martha Wash to Be Honored on World Aids Day Page 13

Volume 25 • Issue 22 • No. 469 • November 22, 2012 • outwordmagazine.com Martha Wash To Be Honored On World Aids Day page 13 SGMC Lights Your World page 8 Brandy and Miguel page 15 Del Shores & Disco page 17 Drag Queens on Ice Pics! page 21 Our Annual Holiday Shopping Guide is on page 12! COLOR GIVE THE GIFT OF FAIR TRADE, CO-OPERATIVE VALUES AND REAL FOOD FOR EVERYONE OPEN DAILY 7AM–10PM (530) 758-2667 • www.davisfood.coop 620 G Street (cross is Sixth) • Davis 95616 YOUR NEIGHBORHOOD GROCERY STORE... & SO MUCH MORE. 2 Outword Magazine November 22, 2012 - December 13, 2012 • Volume 25 • Issue 22 • No. 469 outwordmagazine.com COLOR Ad Name: Gay Males club Closing Date: 3/28/12 Trim: 10.8125x13 Item #: PBL20109925 QC: CS Bleed: none Job/Order #:238788 Pub: Outword Live: 10.3125x12.5 COLOR 594708_02712 10.8125x13 4c Personal Financial Review You’ve found one another and you’re ready to take the next big step — sharing expenses. Talk to someone who can help you navigate the maze of your personal finances and help you take control of your financial situation. Wells Fargo has a wide range of accounts and services including flexible checking and savings accounts, investments, and loans, and we’ll work with you to create a financial strategy that works for you both. Speak with a Wells Fargo banker today, and take your next big step with confidence. wellsfargo.com © 2011 Wells Fargo Bank, N.A. All rights reserved. Member FDIC. (594708_02712) 594708_02712 10.8125x13 4c.indd 1 8/4/11 10:42 AM Outword Letters Staff actualization. -

Author Title Place of Publication Publisher Date Special Collection Wet Leather New York, NY, USA Star Distributors 1983 up Cain

Books Author Title Place of publication Publisher Date Special collection Wet leather New York, NY, USA Star Distributors 1983 Up Cain London, United Kingdom Cain of London 197? Up and coming [USA] [s.n.] 197? Welcome to the circus shirkus [Townsville, Qld, Australia] [Student Union, Townsville College of [1978] Advanced Education] A zine about safer spaces, conflict resolution & community [Sydney, NSW, Australia] Cunt Attack and Scumsystemspice 2007 Wimmins TAFE handbook [Melbourne, Vic, Australia] [s.n.] [1993] A woman's historical & feminist tour of Perth [Perth, WA, Australia] [s.n.] nd We are all lesbians : a poetry anthology New York, NY, USA Violet Press 1973 What everyone should know about AIDS South Deerfield, MA, USA Scriptographic Publications Pty Ltd 1992 Victorian State Election 29 November 2014 : HIV/AIDS : What [Melbourne, Vic, Australia] Victorian AIDS Council/Living Positive 2014 your government can do Victoria Feedback : Dixon Hardy, Jerry Davis [USA] [s.n.] c. 1980s Colin Simpson How to increase the size of your penis Sydney, NSW, Australia Venus Publications Pty.Ltd 197? HRC Bulletin, No 72 Canberra, ACT, Australia Humanities Research Centre ANU 1993 It was a riot : Sydney's First Gay & Lesbian Mardi Gras Sydney, NSW, Australia 78ers Festival Events Group 1998 Biker brutes New York, NY, USA Star Distributors 1983 Colin Simpson HIV tests and treatments Darlinghurst, NSW, Australia AIDS Council of NSW (ACON) 1997 Fast track New York, NY, USA Star Distributors 1980 Colin Simpson Denver University Law Review Denver, CO, -

GLBTRT Newsletter

GLBTRT Newsletter A publication of the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Round Table of the American Library Association http://www.ala.org/glbtrt Reviews (Pages 5 -12): Films Vol. 23, No. 2 ◊ Summer 2011 A Marine Story Two Spirits Youth 365 Days GLBTRT Social in New Orleans Hidden Jumpstart the World The Social Committee Eric Johnson, Tom Fortin, This is the place to see Sleeping Angel and Rod MacNeil and the GLBTR co-chairs, and be seen. A trendy Non-Fiction Anne Moore and Dale McNeill, are looking bar opens into a forward to welcoming everyone at our social lush courtyard and 100 of the Most during at this year’s annual meeting in New offers a fine wine and Influential Gay Orleans. The social will be held at Hotel tequila selection along Entertainers LeMarais (717 Conti Street) in the heart of the with its signature French Quarter from 5:30 pm – 8:00 pm purple cocktail. Binding the God Sunday the 26th. Donations will be gladly accepted to defray the costs of the event. How to Find Love in a Gay Bathhouse Hotel Le Marais is New Orleans’ newest upscale From the Closet to the boutique hotel. According to the hotel website, Courtroom this French Quarter hotel is a modern and upscale sanctuary with four-star amenities and It Gets Better a high level of personal service. The L Life Out Loud A Saving Remnant True Stories Attend Membership Meeting and Participate in Fiction Vote for Over the Rainbow Committee Black Fire Blood Sacraments Over the Rainbow was given ad hoc status a year ago to complete important work meeting the missions of our Head Trip Round Table, specifically creating an annual bibliography of “titles of interest to adult readers that reflect lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or queer (LGBTQ) experiences.”. -

Title Author Publication Year Publisher Format ISBN

Audre Lorde Library Book List Publication Title Author Publisher Format ISBN Year '...And Then I Became Savin-Williams, Ritch Routledge Paperback 9780965699860 Details Gay': Young Men's Stories C ]The Big Gay Book Psy.D., ABPP, John D. 1991 Plume Paperback 0452266211 Details (Plume) Preston ¿Entiendes?: Queer Bergmann, Emilie L; Duke University Readings, Hispanic 1995 Paperback 9780822316152 Details Smith, Paul Julian Press Writings (Series Q) 1st Impressions: A Cassidy James Mystery (Cassidy Kate Calloway 1996 Naiad Pr Paperback 9781562801335 Details James Mysteries) 2nd Time Around (A B- James Earl Hardy 1996 Alyson Books Paperback 9781555833725 Details Boy Blues Novel #2) 35th Anniversary Edition Sarah Aldridge 2009 A&M Books Paperback 0930044002 Details of The Latecomer 1000 Homosexuals: Conspiracy of Silence, or Edmund Bergler 1959 Pagent Books, Inc. Hardcover B0010X4GLA Details Curing and Deglamorizing Homosexuals A Body to Dye For: A Mystery (Stan Kraychik Grant Michaels 1991 St. Martin's Griffin Paperback 9780312058258 Details Mysteries) A Boy I Once Knew: What a Teacher Learned from her Elizabeth Stone 2002 Algonquin Books Hardcover 9781565123151 Details Student A Boy Named Phyllis: A Frank DeCaro 1996 Viking Adult Hardcover 9780670867189 Details Suburban Memoir A Boy's Own Story Edmund White 2000 Vintage Paperback 9780375707407 Details A Captive in Time (Stoner New Victoria Sarah Dreher 1997 Paperback 9780934678223 Details Mctavish Mystery) Publishers Incidents Involving Anna Livia Details Warmth A Comfortable Corner Vincent -

Public Sex I Gay Space

PUBLIC SEX I GAY SPACE Edited by William L. Leap lillllllll Columbia University Press I New York COLUM BIA UNIVERSITY PRESS Publishers Since 189 3 New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright C 1999 Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Public sex/gay spaceI edited by William L. Leap p. em -(Between men-between women) Includes index. ISBN 0-231-10690-4 (cloth). -ISBN 0-231-10691-2(pbk.) 1. Homosexuality. 2. Sex customs-Cross-cultural studies. 3. Public spaces-Health aspects. I. Leap, William. II. Series. HQ76 .PB 1999 306.76'62-dc 21 98-26490 CIP Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. Printed in the United States of America c 109876 54321 p109876 54321 "Tearoom Trade: Impersonal Sex in Public Places" by Laud Humphreys first appeared in Society v. 7, n. 3 (1970). Copyright C 1970 by Laud Humphreys. Reprinted by permission of Transaction Publishers. Contents Preface vii Contributors ix Introduction 1 WILLIAM L. LEA P 1 Reclaiming the Importance of Laud Humphreys's "Tearoom Trade: Impersonal Sex in Public Places" 23 PETER M. NARDI 2 Tearoom Trade: Impersonal Sex in Public Places 29 LAU D HUMPHREYS 3 A Highway Rest Area as a Socially Reproducible Site 55 JOHN HOLLISTER 4 Speaking to the Gay Bathhouse: Communicating in Sexually Charged Spaces 71 IRA TATTELMAN 5 Beauty and the Beach: Representing Fire Island 95 DAVID BERGMAN 6 Sex in "Private" Places: Gender, Erotics, and Detachment in Two Urban Locales 115 WILLIAM L. LEA P 7 Ethnographic Observations of Men Who Have Sex with Men in Public 141 MICHAEL C. -

The Violet Quill Club, 40 Years On

ROUNDTABLE David Bergman assembles the living VQ members The Violet Quill Club, 40 Years On ANDREW HOLLERAN , F ELICE PICANO , & EDMUND WHITE ORTY YEARS AGO, we did not have the Lambda (Penguin, 1988). Christopher Cox became an editor. By the Literary Foundation. We did not have The Gay & middle of the 1990s, all but three of these writers had died of Lesbian Review . There were local newspapers AIDS: Edmund White, Felice Picano, and Andrew Holleran . and magazines, and The Advocate aspired to na - I presented the surviving VQ members with a set of ques - tionwide coverage, but the number of gay presses tions to get their thoughts on the VQ forty years later and its was minuscule (Alyson Publications started up in importance to subsequent gay literature. — D.B. 1980). The major commercial publishers—Random House, Mor - row, St. Martin’s, Viking—were reluctant to publish anything with David Bergman: When you met as the Violet Quill, you were gay content. In the past, publishers had been sued for selling all at the beginnings of your careers. How did you see your fu - pornography when the only sexual act might have been a chaste ture then as “gay writers”? How has it turned out? kiss between men. Perhaps more important was the problem of Edmund White: I thought there would be more of a cross-over Fmarketing. Big publishers didn’t know how to sell books to les - readership, as the Black novel or the Jewish novel achieved. bians or gay men, and they doubted there was a big enough pop - Andrew Holleran: I can only speak for myself about that. -

Press Release 2020

Press Release October 13, 2020 ReQueered Tales releases 3rd Felice Picano novel Marking the 40th Anniversary of the Violet Quill THE BOOK OF LIES by Felice Picano LOS ANGELES—October 13, 2020— ReQueered Tales is restoring award-winning gay and lesbian fiction to print with a focus on mystery, literary and sci-fi genres. Since May 2019, we’ve reintroduced twelve authors to old friends and a new generation of readers. “Based on Picano's involvement with the Violet Quill Club (which included Edmund White and Andrew Holleran), this is an absorbing Henry James-style comedy of manners about how even when some writers find their way out of the closet, others still get left behind.” — The Mail on Sunday Bright, ambitious, and handsome, Ross Ohrenstedt is a high flier in the fashionable field of queer studies. He has just taken a prestigious university position in Los Angeles and has been appointed to oversee the collection of papers and works of a leading light of the gay literary salon known as the Purple Circle. Ross stumbles across a lost work by an unknown author and his quest to identify the mystery writer and achieve the glory of scholastic tenure unveils increasingly bizarre and unbalanced facts about a group of writers who in the 1970s and 1980s broke new ground in the creation of a gay literary sensibility. But the dark truth contained within The Book of Lies is even more startling. With biting wit and a lush sense of place and character, Felice Picano’s daring novel is at once a stylish mystery, a comical roman-à-clef, and a wicked send-up of the new Ivory Tower. -

FEBRUARY 1983 Issue 136 NGTF Plays Crucial Role

NEW YORK'S OLDEST GAY NEWSPAPER FEBRUARY 1983 issue 136 NGTF Plays Crucial Role As participants in the *'Workshop to phrased by the San Francisco based Formulate Recommendations for Preven Coordinating Committee of Gay and tion of Acquired Immune Deficiency Lesbian Health Services, such a policy is Syndrome"' (AIDS), which convened at ' 'reminiscent of misceginatidn blood the Centers for Disease Control office in laws that divided black blood from Atlanta on January 4, 1983, NGTF white," and is **similar in concept to the representatives Dr. Roger Enlow and Dr. World War II rounding-up of Japanese- Bruce Voeiler, along with other metnbers Americans in the western half of the of the gay cx)mmunityp helped to avert a country to mintmixe the possibility of policy change that would have stigma espionage. tized gay men as unsuitable for blood The alternative approach that Enlow donation. They also attended a follow-up and VoeUer recommended was devel meeting on January 6 sponsored by oped with the help of a knowledgeable A»nerican Association of Blood Banks in team of experts which included Tinx Washington that essentially confirmed Westmoreland, Assistant Counsel to the the CDC findings. U.S. Represemative Subcoxtunittee on Health and the En- Henry Waxman of California commented viroiunent of the ~ House of Represen^^ "WATCHED POT" on che outcome of these meetings as tatives, fiopper Deyton, an authority on fc^ows: issues of blood policy and gay health, The Walvhrd Pot, the kttcsi play by It is a positive portrayal of two strong "Tbe NGTF delegates in Atlama aikl and Dr. -

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research CUNY Graduate Center 1995 Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Polly Thistlethwaite CUNY Graduate Center Daniel C. Tsang University of California, Irvine How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_pubs/208 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] ENTRIES 4378-4383 In the 1950s, homophile groups-the Daughters of Bilitis, Mattachine Society, and One, Inc.-built themselves into national organizations by defying U.S. law that prohibited homosexual publications from being distributed by mail. Al though the Comstock Act was changed with One, Inc. v. Olesen in 1958, many sexual minority publications have con tinued to face censorship and harassment from the U.S. Postal Service, U.S. Customs, prison authorities, local gov ernment, and religious and political groups. With the Stonewall Riots of 1969, a national liberation movement emerged. The Los Angeles Advocate (now The Advocate) and Gay Community News date from those days of gay liberation. In the 1970s and 1980s, feminist publica tions began addressing lesbian concerns (see also the Women: Feminist and Special Interest Section). During the 1980s and into the 1990s, gay and lesbian activism re structured to address the AIDS pandemic. Armed with life-affirming and sex-positive analysis, these publications promoted safer sex practices, countering homophobic main stream admonitions to celibacy, blame, and self-loathing. With the rise of such groups as ACT-UP, a brazen sensibil ity ascended that changed the face of the now more gender-unified lesbian and gay press. -

Abstract Gay Men's Literature in the United States

ABSTRACT GAY MEN’S LITERATURE IN THE UNITED STATES (1903 – 1968): UNCOVERING THE BURIED ROOTS OF A QUEER TRADITION Adam W. Burgess, PhD Department of English Northern Illinois University, 2017 Ibis Gómez-Vega, Director This dissertation draws on queer-postmodernism and feminist standpoint theory to investigate and describe aspects of the gay American literary tradition before the historic Stonewall Riots. Specifically, the dissertation offers four points of enquiry: the significance of a text’s displacement in time and location; the successful pulp fiction genre; the importance of intertextuality in establishing discourse; and the complexities of gender and sexuality in fictional texts that incorporate and describe same-sex relationships. There are many works that examine gay American writing in the twentieth-century but much of this scholarship pertains to literature of the 1950s and later; criticism of gay texts published before Stonewall is severely limited. The output of texts by gay American writers begins before the twentieth-century but grows rapidly in scale and clarity of purpose after Whitman, beginning especially with Charles Warren Stoddard’s For the Pleasure of His Company (1903). As a literary historiography, this dissertation treats questions of culture and society alongside close readings of representative texts to argue that the gay literary tradition in the United States is intricately linked to institutions such as medicine, psychology, publication methods, and the law. NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY DE KALB, ILLINOIS MAY 2017 GAY MEN’S LITERATURE IN THE UNITED STATES (1903 – 1968): UNCOVERING THE BURIED ROOTS OF A QUEER TRADITION BY ADAM WAYNE BURGESS © 2017 Adam W. Burgess A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH Doctoral Director: Ibis Gómez-Vega ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many individuals have contributed their time, resources, and expertise to various areas of this project.