Public Sex I Gay Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in the Commonwealth

Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in The Commonwealth Struggles for Decriminalisation and Change Edited by Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in The Commonwealth: Struggles for Decriminalisation and Change Edited by Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites © Human Rights Consortium, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978-1-912250-13-4 (2018 PDF edition) DOI 10.14296/518.9781912250134 Institute of Commonwealth Studies School of Advanced Study University of London Senate House Malet Street London WC1E 7HU Cover image: Activists at Pride in Entebbe, Uganda, August 2012. Photo © D. David Robinson 2013. Photo originally published in The Advocate (8 August 2012) with approval of Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG) and Freedom and Roam Uganda (FARUG). Approval renewed here from SMUG and FARUG, and PRIDE founder Kasha Jacqueline Nabagesera. Published with direct informed consent of the main pictured activist. Contents Abbreviations vii Contributors xi 1 Human rights, sexual orientation and gender identity in the Commonwealth: from history and law to developing activism and transnational dialogues 1 Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites 2 -

HARDWICK and Historiographyt

HARDWICK AND HISTORIOGRAPHYt William N. Eskridge, Jr.* In this article, originally presented as a David C. Baum Me- morial Lecture on Civil Liberties and Civil Rights at the University of Illinois College of Law, Professor William Eskridge critically examines the holding of the United States Supreme Court in Bow- ers v. Hardwick, where the Court held, in a 5-4 opinion, that "ho- mosexual sodomy" between consenting adults in the home did not enjoy a constitutionalprotection of privacy and could be criminal- ized by state statute. Because the Court's opinion critically relied on an originalistinterpretation of the Constitution, Professor Es- kridge reconstructs the history and jurisprudence of sodomy laws in the United States until the present day. He argues that the Hard- wick ruling rested upon an anachronistictreatment of sodomy reg- ulation at the time of the Fifth (1791) or Fourteenth (1868) Amendments. Specifically, the Framersof those amendments could not have understood sodomy laws as regulating oral intercourse (Michael Hardwick's crime) or as focusing on "homosexual sod- omy" (the Court's focus). Moreover, the goal of sodomy regula- tion before this century was to assure that sexual intimacy occur in the context of procreative marriage,an unconstitutional basis for criminal law under the Court's privacy jurisprudence. In short, Professor Eskridge suggests that the Court's analysis of sodomy laws had virtually no connection with the historical understanding of eighteenth or mid-nineteenth century regulators. Rather, the Court's analysis reflected the Justices' own preoccupation with "homosexual sodomy" and their own nervousness about the right of privacy previous Justices had found in the penumbras of the Constitution. -

Twenty-Five Years of Bathhouse Outreach Approaches to Peer Outreach and Play

Twenty-five Years of Bathhouse Outreach Approaches to Peer Outreach and Play Written by Nalini Mohabir In collaboration with ACAS staff team, former staff, and volunteers About the Author: Nalini Mohabir is a long time volunteer, whose involvement with ACAS extends nearly a decade. We found her work and worldview are in tune with ACAS mission and values. In her own words, “As people of colour, it is important to work across the multicultural silos that seek to separate and contain us, as our struggles are shared. Despite recent critiques of solidarity, we still need each other. We are each other’s allies. And I am honoured to be a part of the ACAS family.” Nalini received a Ph.D. in Geography from the University of Leeds, UK. Her areas of specialization include diaspora, migration, and postcolonial studies. Over the last twenty-five years or so, community agencies to be reunited with his family…Two nights before Chris borne out of activist agendas have come under increasing embarked on his journey home, I brought Chris some pressure to act as social service delivery agents, with services congee for supper. He asked me why I “was so nice to delineated by the goals of funders. In the process of him.” I answered, rather instinctively, “We are a family, accountability (to funders, not necessarily communities), a community, if we don’t help each other, who’s going to programs are strictly assessed through outcome help us?” It was that sense of family and community measurements. Such an auditing of experiences obscures that inspired and drove the passion that built first the the richness of our conversations, struggles, and sources of Gay Asian AIDS Project and eventually ACAS.2 strength; it fails to scratch the surface of our emotional lives, or speak to our political investments.1 Consequently, ACAS The impact of similar encounters over time informs our has undertaken this short reflection piece to share the values objective to work in a culturally appropriate manner. -

Yuill, Richard Alexander (2004) Male Age-Discrepant Intergenerational Sexualities and Relationships

Yuill, Richard Alexander (2004) Male age-discrepant intergenerational sexualities and relationships. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2795/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Male Age-Discrepant Intergenerational Sexualities and Relationships Volume One Chapters One-Thirteen Richard Alexander Yuill A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Glasgow Department of Sociology, Anthropology and Applied Social Sciences Faculty of Social Sciences October 2004 © Richard Alexander Yuill 2004 Author's Declaration I declare that the contents of this thesis are all my own work. Richard Alexander Yuill 11 CONTENTS Page No. Acknowledgements Xll Abstract Xll1-X1V Introduction 1-9 Chapter One Literature Review 10-68 1.1 Research problem and overview 10 1.2 Adult sexual attraction to children (paedophilia) 10-22 and young people (ephebophilia) 1.21 Later Transformations (1980s-2000s) Howitt's multi-disciplinary study Ethics Criminological -

Eggplant and Peaches: Understanding Emoji Use on Grindr

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2018 Eggplants and Peaches: Understanding Emoji Usage on Grindr Emeka E. Moses East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Gender and Sexuality Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, and the Social Media Commons Recommended Citation Moses, Emeka E., "Eggplants and Peaches: Understanding Emoji Usage on Grindr" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3379. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/3379 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Eggplants and Peaches: Understanding Emoji Usage on Grindr _____________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Sociology and Anthropology East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Sociology _____________________ by Emeka E. Moses May 2018 _____________________ Dr. Martha Copp, Chair Dr. Lindsey King Dr. Melissa Schrift Keywords: coded language, Grindr, masculinity, identity, gender assumptions, online- interaction, homosexual ABSTRACT Eggplants and Peaches: Understanding Emoji Usage on Grindr by Emeka E. Moses This study focuses on how gay men communicate on the Grindr dating app. Prior research has been conducted on how gay men construct their online identities, however, few studies explore how gay men experience interactions online, negotiate their relationships with other men online, and perceive other users. -

Men Who Have Sex with Men Management a Management Approach for Gps

CLINICAL PRACTICE Men who have sex with men Management A management approach for GPs BACKGROUND At least one in 20 Australian men report sexual contact with another man in their lifetime. Men who have sex with other James Baber men have higher rates of sexually transmitted infections, and are more likely to experience mental health problems and BHB, MBChB, is a sexual use recreational drugs and alcohol. health registrar, Department of Sexual Health, Royal North OBJECTIVE Shore Hospital, Sydney, New This article describes the health problems and sexual behaviour of men who have sex with men and provides an outline South Wales. jbaber@nsccahs. health.nsw.gov.au and an approach to discussing sexuality in general practice. Linda Dayan DISCUSSION BMedSc, MBBS, DipRACOG, Sexuality can be difficult to discuss in general practice. A nonjudgmental approach to men who have sex with men may MM(VenSci), FAChSHM, facilitate early identification of the relevant health issues. MRCMA, is Head, Department of Sexual Health, Royal North Shore Hospital, Director, Sexual Health Services, Northern Sydney Central Coast Area Health Service, Clinical Lecturer, Department of A recent Australian study has shown that 1.7% of men GP is a marker of increased numbers of sexual partners Community and Public Health, identify as exclusively homosexual,1 while 5% of all and higher sexual risk.4 University of Sydney, and in private practice, Darlinghurst, men reported genital homosexual experience through Barriers to discussing sexual health matters with New South Wales. their lifetime.2 nonheterosexuals identified by GPs in the United Kingdom in 2005, included a lack of knowledge of sexual practices Men who have sex with men (MSM) face societal prejudice and terminology.5 Several doctors also recognised that in their lives, and many experience discrimination. -

HIV Prevalence and HIV-Related Sexual Practices Among Men Who

C S & lini ID ca A l f R o e l s Pereira et al., J AIDS Clin Res 2015, 6:1 a e Journal of n a r r DOI: 10.4172/2155-6113.1000415 c u h o J ISSN: 2155-6113 AIDS & Clinical Research Research Article Open Access HIV Prevalence and HIV-Related Sexual Practices among Men Who Have Sex with Men in Portuguese Bathhouses Henrique Pereira1,2*, Samuel Monteiro1, Graça Esgalhado1 and Rosa Marina Afonso1 1University of Beira Interior, Portugal 2UIPES, Psychology and Health Research Unit, (ISPA-IU) Abstract Background: To determine the perceived prevalence (the response of known HIV diagnosis) and trends of HIV infection among mem who have sex with men (MSM) frequenting gay bathhouses; and (2) to identify the risk factors associated sexual practices. Methods: A total of 424 MSM (Mean age 35.64, SD=10.05) recruited through informal social networks and the Internet participated in this study. Most participants were single and self-identified as gay (66.7%). Participants were asked to recall their sexual experiences while visiting a bathhouse for sexual purposes. Results: 9.4% (n=40) of participants reported being HIV positive and approximately 14.5% (n=62) reported not knowing their status. MSM visited the bathhouses 1.76 times per month (SD=2.12) and involved themselves with 3 men (on average) per each visit. Statistically significant differences between having sex with or without a condom were found (p<0.001) reflect that risky behavior occurs (95% CI). Risk practices involving fluid exchange (condom- less practices) were also reported. -

Senate Substitute

2014 SESSION SENATE SUBSTITUTE 14104029D 1 SENATE BILL NO. 14 2 AMENDMENT IN THE NATURE OF A SUBSTITUTE 3 (Proposed by the Senate Committee for Courts of Justice 4 on January 15, 2014) 5 (Patron Prior to Substitute±±Senator Garrett) 6 A BILL to amend and reenact §§ 18.2-67.5:1, 18.2-346, 18.2-348, 18.2-356, 18.2-359, 18.2-361, 7 18.2-368, 18.2-370, 18.2-370.1, 18.2-371, and 18.2-374.3 of the Code of Virginia, relating to 8 sodomy; penalties. 9 Be it enacted by the General Assembly of Virginia: 10 1. That §§ 18.2-67.5:1, 18.2-346, 18.2-348, 18.2-356, 18.2-359, 18.2-361, 18.2-368, 18.2-370, 11 18.2-370.1, 18.2-371, and 18.2-374.3 of the Code of Virginia are amended and reenacted as follows: 12 § 18.2-67.5:1. Punishment upon conviction of third misdemeanor offense. 13 When a person is convicted of sexual battery in violation of § 18.2-67.4, attempted sexual battery in 14 violation of subsection C of § 18.2-67.5, a violation of § 18.2-371 involving consensual intercourse, anal SENATE 15 intercourse, cunnilingus, fellatio, or anilingus with a child, indecent exposure of himself or procuring 16 another to expose himself in violation of § 18.2-387, or a violation of § 18.2-130, and it is alleged in the 17 warrant, information, or indictment on which the person is convicted and found by the court or jury 18 trying the case that the person has previously been convicted within the ten-year 10-year period 19 immediately preceding the offense charged of two or more of the offenses specified in this section, each 20 such offense occurring on a different date, he shall be is guilty of a Class 6 felony. -

Prevalence of and Factors Associated with Oral Sex Among Rural and Urban Malawian Men

Kerwin et al. 2012 Prevalence of and Factors Associated with Oral Sex among Rural and Urban Malawian Men Jason Kerwin * Department of Economics, University of Michigan Rebecca Thornton Department of Economics, University of Michigan Sallie Foley Graduate School of Social Work, University of Michigan March 2012 ABSTRACT Despite medical evidence that female-to-male oral sex carries a much lower risk of HIV transmission than unprotected vaginal intercourse, there has been little research on the practice of fellatio in Africa. We use a sample of 1216 men in rural Malawi and 1537 uncircumcised men in urban Malawi to examine the prevalence of oral sex. While 97 percent of the rural sample and 87 percent of the urban sample reported having had vaginal sex just 2 percent and 12 percent respectively said they had ever received oral sex. Only half of the rural sample, and less than three quarters of the urban sample, reported having heard of oral sex. We find that education and condom use predict oral sex knowledge; in contrast, media exposure and beliefs about HIV do not significantly predict knowledge about oral sex after controlling for other confounding factors. The large gap between sexual activity and oral sex prevalence implies substantial scope for fellatio as another safer sex strategy in Malawi and potentially in other African countries as well. * Corresponding author: Thornton, Department of Economics, 611 Tappan St., Ann Arbor, MI, 48109. Phone: 734- 763-9238. Email: [email protected] . Kerwin: Department of Economics, 611 Tappan St., Ann Arbor, MI, 48109. Email: [email protected] Foley: School of Social Work 1080 S. -

GED Creative Writing Class

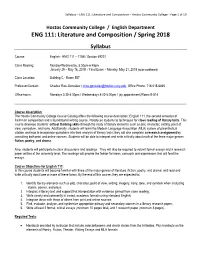

Syllabus – ENG 111: Literature and Composition – Hostos Community College - Page 1 of 10 Hostos Community College / English Department ENG 111: Literature and Composition / Spring 2018 Syllabus Course: English - ENG 111 – 715B / Section 49207 Class Meeting: Monday/Wednesday, 5:30pm-6:45pm January 29 – May 16, 2018 / Final Exam – Monday, May 21, 2018 (to be confirmed) Class Location: Building C - Room 557 Professor/Contact: Charles Rice-González | [email protected]; Office Phone: 718-518-6865 Office hours: Mondays 3:30-4:30pm / Wednesdays 4:00-5:00pm / (by appointment)/Room B-514 Course description: The Hostos Community College Course Catalog offers the following course description: English 111, the second semester of freshman composition and a foundational writing course, introduces students to techniques for close reading of literary texts. This course develops students’ critical thinking skills through the study of literary elements such as plot, character, setting, point of view, symbolism, and irony. Additionally, students will learn the Modern Language Association (MLA) system of parenthetical citation and how to incorporate quotations into their analysis of literary texts; they will also complete a research assignment by consulting both print and online sources. Students will be able to interpret and write critically about each of the three major genres: fiction, poetry, and drama. Also, students will participate in class discussions and readings. They will also be required to submit formal essays and a research paper written at the university level. The readings will provide the fodder for ideas, concepts and experiences that will feed the essays. Course Objectives for English 111: In this course students will become familiar with three of the major genres of literature (fiction, poetry, and drama) and read and write critically about one or more of these forms. -

The Violet Quill Club: Constructing a Post-Stonewall Gay Identity Through Fiction

The Violet Quill Club: Constructing a Post-Stonewall Gay Identity through Fiction Brian Trimboli Senior Honors Thesis Spring 2016 Advisor: Professor of Literary and Cultural Studies Kristina Straub Trimboli 2 Abstract It‘s difficult to define ―literature,‖ let alone ―gay literature.‖ Nonetheless, a group of seven gay male authors, dubbed the Violet Quill Club, met at informal roundtables in New York City to critique each other‘s work in the late 1970s into the early ‘80s, creating a set of works that redefined the way Americans read ―gay‖ novels. These authors published their seminal works during this time, a unique era of sexual freedom in the United States that fell between the Stonewall riots, which mark the beginning of the modern gay rights movement, and the AIDS crisis, which took the lives of four members of the group. The fiction published by the Violet Quill Club established a new gay identity born of New York‘s gay culture, which emphasized sexual liberation and freedom from traditional heterosexual institutions such as marriage. Although this constructed identity was narrowly construed, it influenced a generation of gay men and still resonates within today‘s LGBT rights movement. Trimboli 3 Introduction The definition of ―literature‖ has never been fixed. ―Literature is embedded in the question, ‗What is Literature,‘‖ Michel Foucault told an audience in December 1964 at the Facultés universitaires Saint-Louis in Brussels. ―Literature is not at all made of something ineffable, it is made of something non-ineffable, of something we might consequently refer to, in the strict and original meaning of the term, as ‗fable.‘‖ ―Literature‖ is an even more nebulous category for gay authors producing works with gay themes. -

Research Assistant Experiences in a Gay Bathhouse

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Social Work: School of Social Work Faculty Faculty Publications and Other Works by Publications and Other Works Department 3-4-2020 Conducting Research in Non-Traditional Settings: Research Assistant Experiences in a Gay Bathhouse Michael R. Lloyd Lewis University Michael P. Dentato PhD, MSW Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Brian Kelly Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Hayley Stokar Purdue University - North Central Campus Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/socialwork_facpubs Part of the Social Work Commons Recommended Citation Lloyd, M. R., Dentato, M. P., Kelly, B. L., & Stokar, H. (2020). Conducting Research in Non-Traditional Settings: Research Assistant Experiences in a Gay Bathhouse. The Qualitative Report, 25(3), 615-630. Retrieved from https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol25/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications and Other Works by Department at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Social Work: School of Social Work Faculty Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. © The Qualitative Report, 2020. The Qualitative Report Volume 25 Number 3 Article 4 3-4-2020 Conducting Research in Non-Traditional Settings: Research Assistant Experiences in a Gay Bathhouse Michael R. Lloyd Lewis University, [email protected] Michael P. Dentato Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Brian L. Kelly Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Hayley Stokar Purdue University - North Central Campus, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr Part of the Quantitative, Qualitative, Comparative, and Historical Methodologies Commons, and the Social Work Commons Recommended APA Citation Lloyd, M.