Dr. J. Van Brahana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geohog Times Newsletter of the Department of Geosciences Summer 2019

GeoHog Times Newsletter of the Department of Geosciences Summer 2019 Rebecca Hunt-Foster Dinosaur National Monument Paleontologist and Museum Director BS Earth Science 2003 Software Donations UA Geosciences Projects UA Geosciences Research Grants FY19 Q1-Q3 Grants Awarded Principal Investigators 7 6 Total Awarded Dept Rank in College Data Donations $1.03M 5/19 UA Geosciences Publications Jun 2018 - Jul 2019 Peer Review Papers Non-Peer �eview Papers 67 18 Books Conference Abstracts 3 80 2 Geosciences Department Overview Christopher Liner, Chair in Slovenia. Two of our faculty re- The department received a major ceived competitive Cambridge Faculty software donation from Ikon Sciences This has been a year of changes. In Fellowships to spend time in England. (market value $2.4M). RocDoc is used spring Ralph Davis announced his re- Ted Holland was awarded a full year to analyze well and seismic data, de- tirement from UA and his moving on fellowship at Wolfson College and Ce- termine value and apply quantitative to be VP of Research at the South Da- lina Suarez will spend the spring se- methods to predict rock, fluid and kota School of Mines. Davis was on the mester at Lucy Cavendish College. In pressure properties. Thank you ikon faculty from 1994-2019, and served as all off campus duty assignments, the for supporting our students. Geosciences Department Chair 2008- faculty submits a teaching and ad- As always, the faculty and stu- 2016, a period during which the PhD vising plan explaining how their nor- dents of our department are very program began and the Maurice F. -

2021–2022 University of New Orleans New Student and Family Guide

2021–2022 Parent & Family GUIDE About This Guide CollegiateParent has published this guide in partnership with the University of Arkansas. Our goal is to share helpful, timely information about your student’s college experience and to connect you to relevant campus and community resources. Please refer to the school’s website and contact information below for updates to information in the guide or with questions about its contents. CollegiateParent is not responsible for omissions or errors. This publication was made possible by the businesses and professionals contained within it. The presence of university/ college logos and marks in the guide does not mean that the publisher or school endorses the products or services offered by the advertisers. CollegiateParent is committed to improving the accessibility of our content. When possible, digital guides are designed to meet the PDF/UA standard and Level AA conformance to WCAG 2.1. CollegiateParent Unfortunately, advertisements, campus- 3180 Sterling Circle, Suite 200 provided maps, and other third-party Boulder, CO 80301 content may not always be entirely Advertising Inquiries accessible. If you experience issues with Л (866) 721-1357 the accessibility of this guide, please reach î CollegiateParent.com/advertisers out to [email protected]. ©2021 CollegiateParent. All rights reserved. Design by Kade O’Connor Л (479) 575-5002 Л (855) 264-0001 (Toll Free) ƍ [email protected] For more information, please contact: î family.uark.edu University of Arkansas î uark.campusesp.com New Student & Family Programs – Razorback Family Portal ARKU A688 \ facebook.com/RazorbackParent 1 University of Arkansas H instagram.com/RazorbackParent CONTENTS Welcome to the Razorback Family! ............................... -

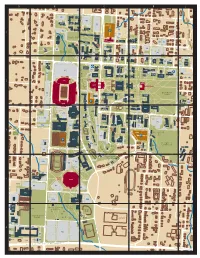

University of Arkansas Parking Rules

1 2 3 4 5 6 University of Arkansas Transit and Parking web site: Parking Map http://parking.uark.edu Map is not drawn to scale. Map last updated July 26, 2017. Subject to change at any time. To Agricultural Research Lot sign designation takes precedence over map designation. Extension Center Changes may have occurred since the last update. For parking information regarding athletic or special events, Legend please visit the Transit and Parking website or call 40A (479) 575-7275 (PARK). Reserved Hall Ave. Faculty/Staff Cleveland St. Resident Reserved (9 months) 41 UUFF Student 40 MHWR MHER ve. A ve. Remote UAPD ve. 37 A Sub A REID Station Parking Meters GAPG Garland GACS A HOTZ Leverett Ave. Lindell Short-term Meters 42 Oakland MHSR 36B A Patient 75 Parking Parking Garage (Metered Parking Available) GACR NWQC 36 Storer Ave. RFCS Taylor St. Under Construction STAQ NWQB JTCD 42 BKST HOUS CAAC 35N 31N ADA Parking Cardwell Ln. ECHP NWQD Loading Zones NWQA Douglas St. Douglas St. 28 FUTR 36A 30 39 35 78 78A Motorcycle Parking Razorback Rd. 31 ve. ADPS A ve. POSC STAB A ZTAS Scooter Parking FWLR 43 38 66 Ave. Gregg HOLC CIOS Research Oliver Lab Parking 27 AFLS Whitham 29 HLTH MART 34 Reserved Scooter Parking ABCM PDCM 10 VS UNHS DDDS KKGS A FWCS D AOPS B 1 68 PBPS Maple St. Maple St. SCHF KDLS Night Reserved Maple St. B WATR ROSE PTSC ARMY Inn at Carnall Hall 14 ALUM ADMN & Ellas Restaurant Parking Parking Admin. 14D HUNT 9 MEMH No Overnight (See list below) 44 26 ARKA 7 CARN Parking Registrar AGRX 14A 1 PEAH ’ 31N 8 SCSW GRAD FIOR 14C FPAC HOEC AGRI 2 47N 76 14B Reagan St. -

2018 Financial Report Supporting Schedules University of Arkansas

2017 -2018 Financial Report Supporting Schedules University of Arkansas Fayetteville Campus Agricultural Experiment Station Cooperative Extension Service Arkansas Archeological Survey Criminal Justice Institute Clinton School ARBON Table of Contents Supporting Exhibits C.l University of Arkansas, Fayetteville 3 C.2 Agricultural Experiment Station 4 C.3 Cooperative Extension Service 5 C.4 Arkansas Archeological Survey 6 C.5 Criminal Justice Institute 7 C.6 Clinton School 8 C.7 AREON 9 Supporting Schedules 1 Schedule of Current Funds Revenues 10 2 Schedule of Current Funds Expenditures 13 3 Schedule of Changes in Service Operations 15 4 Schedule of Changes in Auxiliary Enterprises 16 5 Schedule of Cash, Cash Equivalents, and Investments 17 6 Schedule of Changes in Loan Funds 18 7 Schedule of Changes in Endowments and Similar Funds 19 8 Schedule of Changes in Unexpended Plant Funds 25 9 Schedule of Changes in Renewals and Replacements 31 10 Schedule of Changes in Debt Retirement Funds 43 II Schedule of Bonds Outstanding 45 12 Schedule of Capital Leases Outstanding and Notes Payable 47 13 Schedule of Net Investment in Plant 49 This document supports the University of Arkansas Annual Financial Reports issued forthe fiscal year 2017-18. It is not intended to be used stand-alone, but as support and clarificationfor the amounts reported in the Annual report. 2 Exhibit C.1 University of Arkansas - Fayetteville Statement of Current Funds Revenues, Expenditures, and Other Changes for the Year Ended June 30, 2018 "'ith Comparative Totals forthe Year -

Campusmap.Pdf

A B C D E 40a C L E V E L A N D S T R E E T 41 MHER C L E V E L A N D S T R E E T 40 REID MHWR 37 GARC l i HOTZ a MHSR 75 r 42 T 1 OLIVER AVENUE k 75 e RAZORBACK ROAD NWQC Wilson Park e LINDELL AVENUE 36 r NWQB OAKLAND AVENUE STORER AVENUE Maple Hill 79 C LEVERETT AVENUE BKST Rose l WHITHAM AVENUE ECHP l HOUS JTCD HRDR Hill 35 31 u c D O U G L A S S T R E E T S POSC 28 30 FUTR 36a GARLAND AVENUE 39 43 GTWR 78 78a FWLR Maple Hill HOLR Arboretum 29 ADPS 38 27 AFLS 66 12 STAB 1 HLTH ZTAS CIOS 32 DAVH UNHS DDDS KKGS 34 M A P L E S T R E E T PHMS ACOS 33 AOPS WILSON AVENUE SCHF GREGG AVENUE Sorority Row 10 PARK AVENUE M A P L E S T R E E T ALUM KDLS ADMN ROSE PBPS O HUNT a 26 PTSC ARMY M A P L E S T R E E T 9 AGRX MEMH 44 k 7 R CARN 76 i d 8 PEAH ARKA 25 FPAC LLAW SCSW 2 g WATR HOEC AGRI GRAD e 14b 14c A Arkansas r 2 FBAC b Union o r e CAMPUSMAIN WALK t ARKU Central u MULN WALK m Quad Old Main L A F A Y E T T E S T R E E T Reynolds 72 Stadium Historic Old Main MUSC FNAR CHEM Core Lawn FARM WEST UNST OZAR SDPG 53 CHBC WAHR DISC ARKANSAS AVENUE BAND 4 5 STON 15a RAZS 45 FERR PKAF 6 GIBX COGT 22 ENGR GREGG AVENUE M A R K H A M R O A D GIBS Greek HILL SCEN BELL Theatre GREG MARK JBAR 67 O D I C K S O N S T R E E T a 11 k PHYS SINF FSBC MEEG 73 R CHPN i d D I C K S O N S T R E E T g JBHT e SUST 18 48 FNDR E 71 RAZORBACK ROAD PDTF U Walton KIMP N NANO KASF 73a FSFC 59 50 E 20 19 Arts H O T Z D R I V E BLCA HUMP V Center A W I L L I A M S T R E E T GLAD 3 N 48a YOCM WJWH O M Hotz STADIUM DRIVE HAPG Evergreen R Park MCILROY AVENUE A H Hill 50 WCOB -

Meetings & Conferences of The

MEETINGS & CONFERENCES OF THE AMS AUGUST TABLE OF CONTENTS The Meetings and Conferences section of The most up-to-date meeting and confer- necessary to submit an electronic form, the Notices gives information on all AMS ence information can be found online at: although those who use L ATEX may submit meetings and conferences approved by www.ams.org/meetings. abstracts with such coding, and all math press time for this issue. Please refer to Important Information About AMS displays and similarily coded material the page numbers cited on this page for Meetings: Potential organizers, (such as accent marks in text) must more detailed information on each event. speakers, and hosts should refer to be typeset in LATEX. Visit www.ams.org Invited Speakers and Special Sessions are page 88 in the January 2018 issue of the /cgi-bin/abstracts/abstract.pl. Ques- listed as soon as they are approved by the Notices for general information regard- tions about abstracts may be sent to abs- cognizant program committee; the codes ing participation in AMS meetings and [email protected]. Close attention should be listed are needed for electronic abstract conferences. paid to specified deadlines in this issue. submission. For some meetings the list Abstracts: Speakers should submit ab- Unfortunately, late abstracts cannot be may be incomplete. Information in this stracts on the easy-to-use interactive accommodated. A issue may be dated. Web form. No knowledge of LTEX is MEETINGS IN THIS ISSUE –––––– 2018 –––––––– –––––––– 2020 –––––––– January 15–18 Denver, Colorado p. 894 September 29–30 Newark, Delaware p. 869 March 13–15 Charlottesville, Virginia p. -

Mr. Caleb Osborne and Director Becky Keogh: I Hereby Express My Strong Opposition to Issuing a Permit to Spread Hog Feces and Ur

From: John Van Brahana To: Water Draft Permit Comment Cc: John Van Brahana Subject: C&H Hog Farms Request--Do NOT Approve Date: Thursday, April 06, 2017 10:43:44 AM Mr. Caleb Osborne and Director Becky Keogh: I hereby express my strong opposition to issuing a permit to spread hog feces and urine on fields, and storage of said wastes in lagoons by C&H Hog Farms in Big Creek, near Mt. Judea, Arkansas. It is my understanding that the state of Arkansas requires any facility with a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) discharge permit be required to submit an application for a Construction Permit for the planned facility from a registered professional engineer (P.E). in the Arkansas Department of Environmental Quality, so the design plans can be reviewed and approved prior to construction of the facility. In the case of C&H Hog Farms, I have been unable to find any evidence that a construction permit was ever submitted for approval. The Clean Water Act prohibits anybody from discharging "pollutants" through a "point source" into a "water of the United States" unless they have an NPDES permit. The permit will contain limits on what can be discharged, with monitoring and reporting requirements, and other provisions to ensure that the discharge does not hurt water quality or people's health. In essence, the permit translates general requirements of the Clean Water Act into specific provisions tailored to the operations of each entity discharging pollutants. This Construction Authorization is typically covered under a State Permit. Plans and specifications for the construction of any facility with a planned discharge, which included C&H Farms, are typically submitted with the application package to be reviewed by a Professional Engineer (P.E.) to determine if the design plans were adequate for the facility. -

U.S. Geological Survey Karst Interest Group Proceedings, San Antonio, Texas, May 16–18, 2017

A Product of the Water Availability and Use Science Program Prepared in cooperation with the Department of Geological Sciences at the University of Texas at San Antonio and hosted by the Student Geological Society and student chapters of the Association of Petroleum Geologists and the Association of Engineering Geologists U.S. Geological Survey Karst Interest Group Proceedings, San Antonio, Texas, May 16–18, 2017 Edited By Eve L. Kuniansky and Lawrence E. Spangler Scientific Investigations Report 2017–5023 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN ZINKE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey William Werkheiser, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2017 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov/ or call 1–888–ASK–USGS (1–888–275–8747). For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Kuniansky, E.L., and Spangler, L.E., eds., 2017, U.S. Geological Survey Karst Interest Group Proceedings, San Antonio, Texas, May 16–18, 2017: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2017–5023, 245 p., https://doi.org/10.3133/sir20175023. -

Arkansas Public Higher Education Operating & Capital

Arkansas Public Higher Education Operating & Capital Recommendations 2021-2023 Biennium 7-A Volume 1 Universities Arkansas Division of Higher Education 423 Main Street, Suite 400, Little Rock, Arkansas 72201 October 2020 ARKANSAS PUBLIC HIGHER EDUCATION OPERATING AND CAPITAL RECOMMENDATIONS 2021-2023 BIENNIUM VOLUME 1 OVERVIEW AND UNIVERSITIES TABLE OF CONTENTS INSTITUTIONAL ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR EDUCATIONAL AND GENERAL OPERATIONS ..................................................................................... 3 Background ...........................................................................................................................................................................................3 Table A. Summary of Operating Needs & Recommendations for 2021-2022 ...................................................................................... 7 Table B. Year 2 - Productivity Index ....................................................................................................................................................8 Table C. 2021-22 Four-Year Universities Recommendations .............................................................................................................. 9 Table D. 2021-22 Two-Year Colleges Recommendations ............................................................................................................... -

Thanks This Will Be Added to the Planning Commission Comments

Subject: Re: Charlie Craig State Fish Hatchery preservation Date: Monday, February 15, 2021 10:09:47 AM Thanks this will be added to the planning commission comments Thanks Bill Edwards Mayor of Centerton, Arkansas (479) 795-2750 ext 26 > On Feb 15, 2021, at 10:07 AM, Gail Pianalto wrote: > I am writing to request that you reconsider allowing a 495 family apartment complex (sixteen 3-story buildings < and a golf course) to be installed right beside the Charlie Craig State Fish Hatchery. The hatchery is designated an Audubon Important Bird Area and is critical to so many resident and migrating birds! This will decimate it, and our birds already have so few remaining quality habitat. Please do not allow profit to take precedence over preserving this vital bird habitat. > Respectfully, > Leslie Gail Pianalto > > Sent from my iPhone Subject: Charlie Craig Fish Hatchery Date: Monday, February 15, 2021 1:26:37 PM I am alarmed and distressed to read that a 495 unit apartment complex and golf course is planned for development adjacent to the Charlie Craig State Fish Hatchery. The hatchery is a valuable asset to the city of Centerton and is an oasis in a fast developing area. The hatchery is designated an Audubon Important Bird Area and is critical to many resident and migrating birds. The area around it is an important buffer zone that should be protected from development to ensure that birds have habitat to survive and congregate. I am a frequent visitor to the hatchery and, along with many others, realize that this is a valuable attraction for Centerton. -

Parent & Family Guide

2016 –2017 PARENT & FAMILY GUIDE ABOUT THIS GUIDE CollegiateParent has published this guide in partnership with the University of Arkansas. Please refer to the school’s website and contact information below for updates to the information in this guide or inquiries regarding its contents. CollegiateParent is not responsible for omissions, changes, or inaccurate information contained in this guide. This publication was made possible by the businesses and professionals contained within this parent guide. University/college logos and marks are present in this guide; however, the Publisher and University have in no way endorsed the advertisements or advertisers in this publication. It is also understood that the Publisher and the University cannot endorse any of the claims or products represented within the enclosed advertisements. ©2016 CollegiateParent. All rights reserved. contents Arkansas Guide Comprehensive advice and information for student success CollegiateParent, an | AroundCampus Group company 3180 Sterling Circle, Suite 200 7 | Welcome to the Razorback Family! Boulder, CO 80301 8 | Parent & Family Programs Parent & Family Programs New Student & Family Programs 10 | Meet the 2016 Parent Ambassadors Advertising Inquiries: (866) 721-1357 ARKU A688 14 | Traditions www.aroundcampusgroup.com 1 University of Arkansas 18 | Campus Map Phone: (479) 575-5002 Toll free: (855) 264-0001 20 | Facts About the University E-mail: [email protected] 20 | Student Life Website: parents.uark.edu 26 | Colleges and Schools at the University of Arkansas -

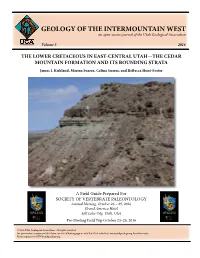

THE LOWER CRETACEOUS in EAST-CENTRAL UTAH—THE CEDAR MOUNTAIN FORMATION and ITS BOUNDING STRATA James I

GEOLOGY OF THE INTERMOUNTAIN WEST an open-access journal of the Utah Geological Association Volume 3 2016 THE LOWER CRETACEOUS IN EAST-CENTRAL UTAH—THE CEDAR MOUNTAIN FORMATION AND ITS BOUNDING STRATA James I. Kirkland, Marina Suarez, Celina Suarez, and ReBecca Hunt-Foster A Field Guide Prepared For SOCIETY OF VERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY Annual Meeting, October 26 – 29, 2016 Grand America Hotel Salt Lake City, Utah, USA Pre-Meeting Field Trip October 23–25, 2016 © 2016 Utah Geological Association. All rights reserved. For permission to copy and distribute, see the following page or visit the UGA website at www.utahgeology.org for information. Email inquiries to [email protected]. GEOLOGY OF THE INTERMOUNTAIN WEST an open-access journal of the Utah Geological Association Volume 3 2016 Editors UGA Board Douglas A. Sprinkel Thomas C. Chidsey, Jr. 2016 President Bill Loughlin [email protected] 435.649.4005 Utah Geological Survey Utah Geological Survey 2016 President-Elect Paul Inkenbrandt [email protected] 801.537.3361 801.391.1977 801.537.3364 2016 Program Chair Andrew Rupke [email protected] 801.537.3366 [email protected] [email protected] 2016 Treasurer Robert Ressetar [email protected] 801.949.3312 2016 Secretary Tom Nicolaysen [email protected] 801.538.5360 Bart J. Kowallis Steven Schamel 2016 Past-President Jason Blake [email protected] 435.658.3423 Brigham Young University GeoX Consulting, Inc. 801.422.2467 801.583-1146 UGA Committees [email protected] [email protected] Education/Scholarship Loren Morton