Dissertation ALL Draft Three

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cold War: a Report on the Xviith IAMHIST Conference, 25-31 July 1997, Salisbury MD

After the Fall: Revisioning the Cold War: A Report on the XVIIth IAMHIST Conference, 25-31 July 1997, Salisbury MD By John C. Tibbetts “The past can be seized only as an image,” wrote Walter Benjamin. But if that image is ignored by the present, it “threatens to disappear irretrievably.” [1] One such image, evocative of the past and provocative for our present, appears in a documentary film by the United States Information Agency, The Wall (1963). Midway through its account of everyday life in a divided Berlin, a man is seen standing on an elevation above the Wall, sending out hand signals to children on the other side in the Eastern Sector. With voice communication forbidden by the Soviets, he has only the choreography of his hands and fingers with which to print messages onto the air. Now, almost forty years later, the scene resonates with an almost unbearable poignancy. From the depths of the Cold War, the man seems to be gesturing to us. But his message is unclear and its context obscure. [2] The intervening gulf of years has become a barrier just as impassable as the Wall once was. Or has it? The Wall was just one of dozens of screenings and presentations at the recent “Knaves, Fools, and Heroes: Film and Television Representations of the Cold War”—convened as a joint endeavor of IAMHist and the Literature/Film Association, 25-31 July 1997, at Salisbury State University, in Salisbury, Maryland— that suggested that the Cold War is as relevant to our present as it is to our past. -

Killing Hope U.S

Killing Hope U.S. Military and CIA Interventions Since World War II – Part I William Blum Zed Books London Killing Hope was first published outside of North America by Zed Books Ltd, 7 Cynthia Street, London NI 9JF, UK in 2003. Second impression, 2004 Printed by Gopsons Papers Limited, Noida, India w w w.zedbooks .demon .co .uk Published in South Africa by Spearhead, a division of New Africa Books, PO Box 23408, Claremont 7735 This is a wholly revised, extended and updated edition of a book originally published under the title The CIA: A Forgotten History (Zed Books, 1986) Copyright © William Blum 2003 The right of William Blum to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Cover design by Andrew Corbett ISBN 1 84277 368 2 hb ISBN 1 84277 369 0 pb Spearhead ISBN 0 86486 560 0 pb 2 Contents PART I Introduction 6 1. China 1945 to 1960s: Was Mao Tse-tung just paranoid? 20 2. Italy 1947-1948: Free elections, Hollywood style 27 3. Greece 1947 to early 1950s: From cradle of democracy to client state 33 4. The Philippines 1940s and 1950s: America's oldest colony 38 5. Korea 1945-1953: Was it all that it appeared to be? 44 6. Albania 1949-1953: The proper English spy 54 7. Eastern Europe 1948-1956: Operation Splinter Factor 56 8. Germany 1950s: Everything from juvenile delinquency to terrorism 60 9. Iran 1953: Making it safe for the King of Kings 63 10. -

SEPTEMBER 17, 1987 35¢ PER COPY 5747 in Review: First Soviet Jews in 4 Years Arrive in R.I

*******~*****************5-D I GI""!'" 02906 241 1/3!!88 ** 31 R.!~ JE~ISH HISTORICAL ASSOCIA~IG~ 1.36 SESfHOI\JS E.,..: Inside: ~ROVIDENCE~ RI ·)2906 From The Editor, page 4 Around Town, page 8 THE ONLY ENGLISH-JEWISH WEEKLY IN R.I. AND SOUTHEAST MASS. , VOLUME LXXIV, NUMBER 42 THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 17, 1987 35¢ PER COPY 5747 In Review: First Soviet Jews In 4 Years Arrive In R.I. A Year Of Debate The Journey Home, Those Left Behind (First In A Series) bloodiest terrorist foray here in by Andrew Muchin more than two years. by Roberta Segal NEW YORK (JTA) - Jews NEW YORK - Long-time Special to the Rhode Island Herald argued throughout 5747, perhaps Jewish refusenik David Goldfarb Part Three of a Three Part Series more than during any recent year. left his hospital bed and then the Zhanna Volinsky was a good As individuals and organizations, Soviet Union with his wife Cecilia Soviet citizen. Authorities, in fact, Jews took on adversaries and aboard the jet of industrialist held her as an example of a Jew perceived adversaries of Israel and Armand Bammer. who was able to achieve equally Jewry, and - no less vociferously NEW YORK - Nobel Prize with a Russian. - each other. winners included three Jews: For a long while, Zhanna Some of the talk only author Elie Weisel of New York, believed in the system of her threatened action, such as Israel's for Peace; and Dr. Rita motherland. She was given the oft-endangered national unity Levi-Montalcine of Rome and the opportunity to study at a leading government that held together ,U.S. -

Here the Policymaking Value of Fresh Thinking and Cognitive Diversity Combined with Seasoned Expertise and Accumulated Wisdom Has Long Been Recognised

GLOBAL STRATEGY FORUM Lecture Series 2018 - 2019 www.globalstrategyforum.org Lord Lothian, Mr. Radek Sikorski and Sir Malcolm Rifkind Sir John Chilcot and Lord Lothian Mr. James Barr and Lord Lothian Professor Charles Garraway and Lord Lothian Lord Lothian and Mr. Ben Macintyre Dr. Kori Schake and Lord Lothian Mr. Matthew Rycroft and Lord Lothian Lord Lothian and Mr. Gordon Corera www.globalstrategyforum.org GLOBAL STRATEGY FORUM Lecture Series 2018 - 2019 3 www.globalstrategyforum.org NOTES 4 www.globalstrategyforum.org PRESIDENT’S FOREWORD It gives me great pleasure to introduce this, the thirteenth edition of GSF’s annual lecture publication. In these pages you will once again find a full record of the extensive events programme which we delivered during the course of our 2018-2019 series. Topics and regions predictably included Brexit, China, Russia, the Middle East and the US, as well the big global issues of the day: climate change, terrorism, globalisation, cybersecurity. But the breadth and range of countries, region and topics covered was striking, from Brazil to Yemen, and from international development and the Commonwealth to the return of great power rivalry, attracting record audiences along the way. Unsurprisingly, much focus and political capital has continued to lie with the Brexit process, which has dominated the public discourse. But in GSF debates throughout the year on the UK’s role in the world, I observed a clear desire – demand, even - for substance to be given to the concept of ‘Global Britain’ and a firm eschewal of any reduction in our engagement in world events. During this period of change and uncertainty in the UK and beyond, the answers to the many complicated questions of policy and strategy facing us remain elusive, but GSF’s mandate requires us to continue to strive to seek them. -

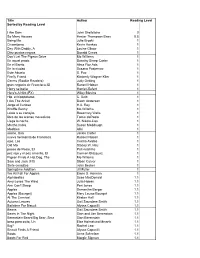

Reading Counts

Title Author Reading Level Sorted by Reading Level I Am Sam John Shefelbine 0 So Many Houses Hester Thompson Bass 0.5 Being Me Julie Broski 1 Crisantemo Kevin Henkes 1 Day With Daddy, A Louise Gikow 1 Diez puntos negros Donald Crews 1 Don't Let The Pigeon Drive Mo Willems 1 En aquel prado Dorothy Sharp Carter 1 En el Barrio Alma Flor Ada 1 En la ciudad Susana Pasternac 1 Este Abuelo S. Paz 1 Firefly Friend Kimberly Wagner Klier 1 Germs (Rookie Readers) Judy Oetting 1 gran negocio de Francisca, El Russell Hoban 1 Harry se baña Harriet Ziefert 1 Here's A Hint (FX) Wiley Blevins 1 Hip, el hipopótamo C. Dzib 1 I Am The Artist! Dawn Anderson 1 Jorge el Curioso H.A. Rey 1 Knuffle Bunny Mo Willems 1 Léale a su conejito Rosemary Wells 1 libro de las arenas movedizas Tomie dePaola 1 Llega la noche W. Nikola-Lisa 1 Martha habla Susan Meddaugh 1 Modales Aliki 1 noche, Una Jackie Carter 1 nueva hermanita de Francisca Russell Hoban 1 ojos, Los Cecilia Avalos 1 Old Mo Stacey W. Hsu 1 paseo de Rosie, El Pat Hutchins 1 pez rojo y el pez amarillo, El Carmen Blázquez 1 Pigeon Finds A Hot Dog, The Mo Willems 1 Sam and Jack (FX) Sloan Culver 1 Siete conejitos John Becker 1 Springtime Addition Jill Fuller 1 We All Fall For Apples Emmi S. Herman 1 Alphabatics Suse MacDonald 1.1 Amy Loves The Wind Julia Hoban 1.1 Ann Can't Sleep Peri Jones 1.1 Apples Samantha Berger 1.1 Apples (Bourget) Mary Louise Bourget 1.1 At The Carnival Kirsten Hall 1.1 Autumn Leaves Gail Saunders-Smith 1.1 Bathtime For Biscuit Alyssa Capucilli 1.1 Beans Gail Saunders-Smith 1.1 Bears In The Night Stan and Jan Berenstain 1.1 Berenstain Bears/Big Bear, Sma Stan Berenstain 1.1 beso para osito, Un Else Holmelund Minarik 1.1 Big? Rachel Lear 1.1 Biscuit Finds A Friend Alyssa Capucilli 1.1 Boots Anne Schreiber 1.1 Boots For Red Margie Sigman 1.1 Box, The Constance Andrea Keremes 1.1 Brian Wildsmith's ABC Brian Wildsmith 1.1 Brown Rabbit's Shape Book Alan Baker 1.1 Bubble Trouble Mary Packard 1.1 Bubble Trouble (Rookie Reader) Joy N. -

CALIFORNIA RED a Life in the American Communist Party

alifornia e California Red CALIFORNIA RED A Life in the American Communist Party Dorothy Ray Healey and Maurice Isserman UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESS Urbana and Chicago Illini Books edition, 1993 © 1990 by Oxford University Press, Inc., under the title Dorothy Healey Remembers: A Life in the American Communist Party Reprinted by arrangement with Oxford University Press, Inc., New York, New York Manufactured in the United States of America P54321 This book is printed on acidjree paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Healey, Dorothy. California Red : a life in the American Communist Party I Dorothy Ray Healey, Maurice Isserman. p. em. Originally published: Dorothy Healey remembers: a life in the American Communist Party: New York: Oxford University Press, 1990. Includes index. ISBN 0-252-06278-7 (pbk.) 1. Healey, Dorothy. 2. Communists-United States-Biography. I. Isserman, Maurice. II. Title. HX84.H43A3 1993 324.273'75'092-dc20 [B] 92-38430 CIP For Dorothy's mother, Barbara Nestor and for her son, Richard Healey And for Maurice's uncle, Abraham Isserman ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work is based substantially on a series of interviews conducted by the UCLA Oral History Program from 1972 to 1974. These interviews appear in a three-volume work titled Tradition's Chains Have Bound Us(© 1982 The Regents of The University of California. All Rights Reserved. Used with Permission). Less formally, let me say that I am grateful to Joel Gardner, whom I never met but whose skillful interviewing of Dorothy for Tradition's Chains Have Bound Us inspired this work and saved me endless hours of duplicated effort a decade later, and to Dale E. -

Daily Iowan (Iowa City, Iowa), 1950-06-13

On the Insid, , PlaylChool 10 Open ... Paqe :J dntJ er"'''17 bUT wlUIHI _UeN ....... Slate Amateur Goll Tourney GlllHenMlI·ers. IItn ..... ... Paqe 4 • laT. N : lew.... Bla'h " fine Arta festival at ~~~')/&J M~,.. 'Jt; lew, 13 • ... Paqe!1 ESI. 1868 - AP Leaaed Wire, AP Wirephoto, UP 1.eaHd WIre - Pive Cenia Iowa City. Iowa. Tuesday. JWl~ 13, 1950 -; Vol. .... ·No. 212 ii............ -- ....~~ ~-------~~~~~------~~~~~ Trum'on Discusses' Tax Congres~Oebates- Progrbm at ponference Fishing Luck, WASHINGTON (AP)-President Truman diseuued taxes with hjs congressional leaders Monday in a general review of the Or Is ,If Skill! I still filr from complete legislative program. .' Final adjotlllment was so far out of sight that it wasn't cven * * * ' t~Jk~ .about a~ the White House conference, Speaker Sam Ray- WASHINGTON (JP) _ FishIng WASHlNGTON (A.P)-'The seDate otcd Monday to con· b~rn reported. - . Is skill, not luck, congress was . tiuue fedenJ reot controls through lQ'5() aod to give (,10mmuniUcs .Others pl'csent were VIce Pres. Brllt"ISh N . !~~~c:~~::i'a a;OS~n::f~~~ ;:;:~~: authority to extend them for aoother Ijx month beyood that. ident All1en Barkley, Scnate demo. ~ ewsman mept ruling that Ilald big fIsh arc the bill DOW goes to the house. Dmlocratic Leader Johll cratic Leader Scott Lucas of it. ' ' caught by chance. McCormacllI . of MasSachusetts said debate will" ,tart there today. ~~r ;on:n :c~u;:ma~:~~~~!~ s eulers or "This business ot fishlrtg Is of Howe seotiment is geucrllUy regarded as closely divided, and Botl, R" f thc utmost skllJ," said Rep J, Caleb sachuseitk. -

Central Intelligence Agency FOIA Request Logs, 2000-2005

Central Intelligence Agency FOIA request logs, 2000-2005 Brought to you by AltGov2 www.altgov2.org/FOIALand ... , Calendar Year 2000 FOIA Case Log Creation Date Case Number Case Subject 03-Jan-00 F-2000-00001 IMPACT VISA CARD HOLDERS 03-Jan-0O F-2000-00003 WILLIAM CHARLE BUMM JSC RADEL, LTD; ELTEK COMPANY WIDEBAND SYSTEMS DIGITAL FREQUENCY DISCRIMINATOR; ED 03-Jan-00 F-2000-00004 BATKO OR BATKO INTERNATIONAL; COLONEL SERGEY SUKARAEV 03-Jan-0O F-2000-00005 INFO ON FATHER 04-Jan-00 F-2000-00006 JOHN CHRISLAW 04-Jan-00 F-2000-00007 1999 BOMBING OF CHINESE EMBASSY IN BELGRADE, YUGOSLAVIA. 04-Jan-00 F-2000-00008 COMMANDER IAN FLEMING 04-Jan-00 F-2000-00009 MALCOLM X AND ELIJAH MUHAMMAD AND HIS SON, AKBAR MUHAMMAD AND THE NATION OF ISLAM 04-Jan-00 F-2000-00010 WILLIAM STEPHENSON 04-Jan-00 F-2000-00011 SIX DECEASED INDIVIDUALS WITH CRIMINAL BACKGROUND 04-Jan-00 F-2000-00012 INFO ON ARGENTINA 04-Jan-00 F-2000-00013 ENRIQUE FUENTES LEON, MANUEL MUNOZ ROCHA, AND ERNESTO ANCIRA JR. 04-Jan-00 F-2000-00014 SOVIET ESPIONAGE IN AND AGAINST THE UNITED STATES 04-Jan-00 F-2000-00015 SOVIET ESPIONAGE IN AND AGAINST THE UNITED STATES SPECIFIC INFO ON CIA POSITIONS RELATING TO THE INFORMATION SYSTEMS CONTACTS AND 04-Jan-00 F-2000-00016 PURCHASING- OFFICERS 04-Jan-00 F-2000-00017 MKULTRA CDROMS 04-Jan-00 F-2000-00018 CIA PROJECTS ON OR AROUND 9 APRIL 1959 04-Jan-00 F-2000-00019 JERZY PAWLOWSKI 04-Jan-00 F-2000-00020 PERSONNEL FILES OF ALDRICH AMES 05-Jan-00 F-2000-00026 PERSONNEL FILES OF ALDRICH AMES 05-Jan-00 F-2000-00027 32 PAGE LETTER AND TWO TDK TAPES ON HER PROBLEMS 05-Jan-00 F-2000-00028 EMERSON T. -

Download Program

Allied Social Science Associations Program BOSTON, MA January 3–5, 2015 Contract negotiations, management and meeting arrangements for ASSA meetings are conducted by the American Economic Association. Participants should be aware that the media has open access to all sessions and events at the meetings. i Thanks to the 2015 American Economic Association Program Committee Members Richard Thaler, Chair Severin Borenstein Colin Camerer David Card Sylvain Chassang Dora Costa Mark Duggan Robert Gibbons Michael Greenstone Guido Imbens Chad Jones Dean Karlan Dafny Leemore Ulrike Malmender Gregory Mankiw Ted O’Donoghue Nina Pavcnik Diane Schanzenbach Cover Art—“Melting Snow on Beacon Hill” by Kevin E. Cahill (Colored Pencil, 15 x 20 ); awarded first place in the mixed media category at the ″ ″ Salmon River Art Guild’s 2014 Regional Art Show. Kevin is a research economist with the Sloan Center on Aging & Work at Boston College and a managing director at ECONorthwest in Boise, ID. Kevin invites you to visit his personal website at www.kcahillstudios.com. ii Contents General Information............................... iv ASSA Hotels ................................... viii Listing of Advertisers and Exhibitors ...............xxvii ASSA Executive Officers......................... xxix Summary of Sessions by Organization ..............xxxii Daily Program of Events ............................1 Program of Sessions Friday, January 2 ...........................29 Saturday, January 3 .........................30 Sunday, January 4 .........................145 Monday, January 5.........................259 Subject Area Index...............................337 Index of Participants . 340 iii General Information PROGRAM SCHEDULES A listing of sessions where papers will be presented and another covering activities such as business meetings and receptions are provided in this program. Admittance is limited to those wearing badges. Each listing is arranged chronologically by date and time of the activity. -

Walter Benjamin and Bertolt Brecht This Page Intentionally Left Blank Erdmut Wizisla

Walter Benjamin and Bertolt Brecht This page intentionally left blank Erdmut Wizisla Walter Benjamin and Bertolt Brecht – the story of a friendship translated by Christine Shuttleworth Yale University Press New Haven and London First published as Walter Benjamin und Bertolt Brecht – Die Geschichte einer Freundschaft by Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt, 2004. First published 2009 in English in the United Kingdom by Libris. First published 2009 in English in the United States by Yale University Press. Copyright © 2009 Libris. Translation copyright © 2009 Christine Shuttleworth. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Designed by Kitzinger, London. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Control Number: 2009922943 isbn 978-0-300-13695-1 (hardcover : alk. paper) A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ansi/niso z39.48‒1992 (Permanence of Paper). 10987654321 Contents List of Illustrations vi Publisher’s Note vii Chronology of the Relationship ix Map and time chart of Benjamin and Brecht xxvi I A Significant Constellation May 1929 1 A Quarrel Among Friends 9 II The Story of the Relationship First Meeting, A Literary Trial, Dispute over Trotsky, 1924–29 25 Stimulating Conversations, Plans for Periodicals, ‘Marxist Club’, -

The Ecological Economics of Sustainability: Making Local and Short-Term Goals Consistent with Global and Long-Term Goals

------- THE WORLD BANK SECTOR POLICY AND RESEARCH STAFF Environment Department The Ecological Economics of Sustainability: Making Local and Short-Term Goals Consistent with Global and Long-Term Goals Robert Costanza Ben Haskell Laura Cornwell Herman Daly and Twig Johnson June 1990 Environment Working Paper No. 32 This paper has been prepared for internal use. The views and interpretations herein are those of the author(s) and should not be attributed to the World Banlc, to its affiliated organizations or to any individual acting on their behalf. ~----------------- --- ---- -~~------ -- -------- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors are Robert cCostanza , Associate Professor at the Center for Marine and Estuarine Studies, University of Maryland, and Ben Haskell and Laura Cornwell, who are both Research Associates at the same Center. Herman Daly is Senior Economist in the Environmental Policy and Research Division of the World Bank, and Twig Johnson is Acting Director at the USAID Office of Forestry, Environment and Natural Resources Department. Together they were the organizers for the 'Ecological Economics of Sustainability' Conference, the abstracts of which are presented here. Departmental Working Papers are not formal publications of the World Bank. They present preliminary and unpolished results of country analysis or research that are circulated to encourage discussion and comment; citation and the use of such a paper should take account of its provisional character. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the authors and should not be attributed in any manner to the World Bank, to its affiliated organizations, or to members of its Board of Executive Directors or the countries they represent. -

Shades of Green: a Comparative Analysis of U.S

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2016 Shades of Green: A Comparative Analysis of U.S. Green Economies Jenna Ann Lamphere University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Other Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Lamphere, Jenna Ann, "Shades of Green: A Comparative Analysis of U.S. Green Economies. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2016. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/4144 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Jenna Ann Lamphere entitled "Shades of Green: A Comparative Analysis of U.S. Green Economies." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Sociology. Jon Shefner, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Robert Emmet Jones, Sherry Cable, Alex Miller Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Shades of Green: A Comparative Analysis of U.S. Green Economies A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee Jenna Ann Lamphere December 2016 Copyright © 2016 by Jenna A.