Kalla Yarning at Matagarup: Televised Legitimation and the Limits of Heritage-Making in the City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November 2015

History West, November 2015 November 2015 GENERAL MEETING The next meeting at Stirling House is on Wednesday 18 November at 6pm. Dr Bob Reece will present a paper entitled Yagan and Other Prominent Swan River Aborigines. Refreshments available from 5.30pm; Bookshop open until 6pm In recent years, Yagan has become a hero figure for the descendants of the original Aboriginal owners of Swan River and a by-word for their response to British settlement of Swan River Colony in the years after June 1829. They see him as a resistance figure (‘freedom fighter’, if you like) who offered armed opposition to the settlers, their expropriation without compensation of traditional lands and their disdain for an ancient Aboriginal culture. Aboriginal society lacked any political hierarchy, but Yagan represented a new form of leadership. Fearful of his violent exploits which saw him declared an outlaw with a price on his head, the small and vulnerable settler population heaved a collective sigh of relief in 1833 when news came that he been treacherously shot by a thirteen year old boy for the reward. The emergence of Aboriginal people on to the national political stage after the 1967 referendum accelerated the need for Aboriginal hero figures who could symbolise resistance to European settler dominance both in the past and the present. In Western Australia, Yagan was a familiar figure but the erection of a bronze statue in his honour on Heirisson Island in 1984 raised his profile in more than the obvious way. From a fresh examination of the contemporary sources, this paper will offer a perspective on Yagan (and by extension other notable Swan River Aboriginal figures of his time) that will hopefully assist us in seeing him as he was rather than what he has become. -

8 April 1987145 451

[Wednesday. 8 April 1987145 451 We are not prepared to accept the Iiegistutiute AssembIll experiment at the expense of our children. Wednesday. 8 April 1987 Your petitioners therefore pray that you will take whatever action is necessary to have the Post Release Programme located- THE SPEAKER (Mr Barnett) took the Chair at another location, and your petitoners as at 2.1 5 pm. and read prayers. in duty bound, will ever pray. The petition bears 363 signatures. I certify that ENVIRONMENT: OLD SWAN BREWERY it conforms to the Standing Orders of the Legis- Demolition: Petition lative Assembly. MR MacKINNON (Murdoch-Lecader of The SPEAKER: I direct that the petition be the Opposition) [2.1 7 pm]: I present a petition brought to the Table of the House. to the House couched in the following terms- (See petition No. 18.) To the Honourable the Speaker and ENVIRONMENT: Members of the Legislative Assembly in OLD SWAN BREWERY Parliament assembled. The petition of the Rode velopinen i: Petition under-signed respectfully showeth we pro- MR LEWIS (East Melville) [2.19 pm]: I test strongly against the proposed develop- present a petition from 98 residents of Western ment for the old Brewery and Stables sites Australia in the following terms- and urge that the buildings be demolished To: The Honourable the Speaker and and the area be converted to parkland Members of the Legislative Assembly of under the control of the King's Park the Parliament of Western Australia in Par- Board. liament assembled. Your Petitioners as in duty bound, will We the undersigned request that the Par- ever pray. -

Apo-Nid63329.Pdf

State of Australian Cities Conference 2015 Image Analysis of Urban Design Representation Towards Alternatives Robyn Creagh Centre for Sport and Recreation Research, Curtin University Abstract: This paper is a critical exploration of visual representation of urban places. This paper examines extracts from one Australian case study, the document An Urban Design Framework: A Vision for Perth 2050 (UDF), and makes comparisons between prior analysis of urban plans and the visual language of the UDF. Three alternative representations are then briefly discussed to explore some ways in which urban places are understood and communicated outside of urban design and planning frameworks. This paper is the start of a project rather than the culmination and sketches future directions of enquiry and possibilities for practice. The overall focus of this analysis is to reveal the way in which attitudes to place, roles and process are revealed through visual sections of city vision documents. The paper concludes that the visual representations in the UDF are not neutral and that these representations correspond to discursive traits seen in urban plans. These traits conceptualise place history as unproblematic and without authors, construct authority within technical process, and limit the role of place occupants as opposed to designer or planner. Parallel to moves to challenge the language of urban plans this paper illustrates that it is also important to challenge the visual language of urban design. 1. Visualising urban design for Australian cities Urban design plans and frameworks are part of the tools and outputs of city making in Australia. The way that these documents are constructed tells us about the built environment profession’s understanding of urban places and the perceived role of various players in this context. -

Reconciliation Action Plan

1 Reconciliation Action Plan REFLECT April 2018 – April 2019 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENT OF COUNTRY We acknowledge the Whadjuk Nyoongar people, Traditional Owners of the lands and waters where the City of Perth is today and pay our respects to Elders past and present. Nyoongar peoples are the original inhabitants and Traditional Owners of the South West of Western Australia. While Nyoongar is identified as a single language there are variations in both pronunciation and spelling – Noongar, Nyungar, Nyoongar, Nyoongah, Nyungah, Nyugah, Yungar and Noonga. The City of Perth uses ‘Nyoongar’ which is reflected throughout this document except when specifically referring to an external organisation that utilises alternative spelling. ALTERNATIVE FORMATS An electronic version of the City of Perth’s Reflect City of Perth Telephone: (08) 9461 3333 Reconciliation Action Plan 2018-19 is available from 27 St Georges Terrace, Perth Email: [email protected] www.perth.wa.gov.au. This document can be provided GPO Box C120, Perth WA 6839 in alternate formats and languages upon request. 3 2 Laurel Nannup (artwork opposite) Message from Going Home to Mum and Dad (2016) Woodblock print City of Perth CEO 64.5 x 76.5cm I am delighted to present the City of Perth’s first I strongly encourage all staff to develop their Reconciliation Action Plan (RAP), which represents knowledge of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander a significant step in the City’s journey towards histories and cultures, particularly that of the Whadjuk reconciliation with the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Nyoongar community, whilst striving diligently Islander communities. toward achieving the deliverables of the City’s RAP. -

Registration Test Decision

Registration test decision Application name Whadjuk People Name of applicant Clive Davis, Nigel Wilkes, Dianne Wynne, Noel Morich, Trevor Nettle State/territory/region Western Australia NNTT file no. WC11/9 Federal Court of Australia file no. WAD242/2011 Date application made 23 June 2011 Date of Decision 11 October 2011 Name of delegate Lisa Jowett I have considered this claim for registration against each of the conditions contained in ss. 190B and 190C of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cwlth). For the reasons attached, I am satisfied that each of the conditions contained in ss. 190B and C are met. I accept this claim for registration pursuant to s. 190A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cwlth). Date of Reasons: 1 November 2011 ___________________________________ Lisa Jowett Delegate of the Native Title Registrar pursuant to sections 190, 190A, 190B, 190C, 190D of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cwlth) under an instrument of delegation dated 24 August 2011 and made pursuant to s. 99 of the Act. Reasons for decision Table of contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 3 Application overview............................................................................................................... 3 Registration test ........................................................................................................................ 3 Information considered when making the decision ........................................................... -

Perth Causeway Bridges

Heritage Panel perth’s causeway bridges - a story of three crossings - HISTORY OF THE CAUSEWAY SITE THIRD CAUSEWAY CROSSING 1952 EMINENT PERSONS ASSO CI ATED WITH THE 1952 BRIDGES Local indigenous people had been crossing the river on foot for thousands of years before the first The 1867 bridges were modified several times during their life. In 1899 they were widened by Sir Ross McLarty Premier of Western Australia 1947 - 1953 recorded European visit when sailors from Dutch navigator Willem de Vlamingh’s ships rowed the addition of a footpath, widened again and strengthened in 1904 and widened again in 1933. Mr Jim Young Commissioner Main Roads WA 1941 - 1953 up the river in January 1697, giving the name ‘Swan’ to the river, because of the prevalence of Serious planning to replace the bridges took place during the 1930s. In this period considerable Mr Digby Leach Commissioner Main Roads WA 1953 - 1964 black swans. Just over 100 years later, in 1801, the French expedition, under the command of work was done to dredge the river to provide much wider navigation channels. Nicolas Baudin, visited Western Australia. Sailors from the Naturaliste ventured up the river to the Mr Ernie Godfrey Bridge Engineer Main Roads WA 1928 - 1957 In 1944 Main Roads Bridge Engineer E.W.C. Godfrey submitted a proposal to Commissioner J.W. Causeway site and named the island at the centre of the area after midshipman Francois Heirisson. Young to build two new bridges upstream of the existing ones with a 19 metre wide deck. The Later still, Captain Stirling, in exploring the river in 1827, had difficulties in having to have his combined length of the two bridges was to be 341 metres. -

Precinct 8 Burswood Island to Maylands Peninsula (Causeway Bridge to Bath Street Reserve)

Precinct 8 Burswood Island to Maylands Peninsula (Causeway Bridge to Bath Street Reserve) 1 Summary Burswood Island to Maylands Peninsula (Causeway Bridge to Bath Street Reserve) The Swan River takes the form of broad, graceful regular meanders upstream of Heirisson Island to Maylands Peninsula. The wide channel seasonally inundates the remaining flat alluvial sediments, such as Maylands Peninsula. The landform is particularly attractive as it highlights the river meander bends with the flat peninsulas nesting into steeply sloping escarpments of the opposite banks. The escarpment line curves in a parabolic form with the low Burswood Island Resort is a large modern development which points being the peninsulas at either end and the central curve stands out rather than complements the river environment, tapering to a uniform, higher ridge. however the landscaped gardens and highly maintained appearance,, is more attractive than the adjacent railway reserve There is little natural riparian vegetation along the foreshore in land. At present, the northern point of the peninsula is currently this section due to extensive landfill and intensive land use in the being developed as a major transport node to bypass the main area. One of the most attractive vegetation complexes is the city area and consequently is an unattractive construction site. samphire flats and fringing reed communities at the Maylands There is a mixture of high density flats and single residential Peninsula. Remnant flooded gum and paperbark communities blocks along the Rivervale foreshore and the land west of are present along the southern foreshore between Belmont Park Abernethy Road is currently being redeveloped for residential Racecourse and Abernethy Road, however these complexes land use. -

From Perth's Lost Swamps to the Beeliar Wetlands

Coolabah, No. 24&25, 2018, ISSN 1988-5946, Observatori: Centre d’Estudis Australians i Transnacionals / Observatory: Australian and Transnational Studies Centre, Universitat de Barcelona Reimagining the cultural significance of wetlands: From Perth’s lost swamps to the Beeliar Wetlands. Danielle Brady Edith Cowan University [email protected] Jeffrey Murray Australian Army Copyright©2018 Danielle Brady & Jeffrey Murray. This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the author and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged, in accordance with our Creative Commons Licence. Abstract: The history of Perth, Western Australia, has been characterised by the incremental loss of its wetlands. While disputes about wetlands are often framed solely in terms of the environment, they are places of cultural significance too. The extensive wetlands of central Perth, food gathering and meeting places for Noongar people are now expunged from the landscape. Urban dwellers of Perth are largely unaware that the seasonal lakes and wetlands of the centre of the city were the larders, gardens, hideouts, dumps and playgrounds of previous generations; both Noongar and Settler. The loss of social memory of these lost cultural/natural places entails the framing of wetlands as aberrant and continues to influence Perth’s development and the sense of place of its inhabitants. Reimagining Perth’s Lost Wetlands was a project which attempted to reimagine the pre-colonial landscape using archival material. Reimagining the past allows connections to be made to the last remaining wetlands in the wider metropolitan area. The fight to save the Beeliar Wetlands in southern suburban Perth as a cultural/natural place illustrates the changing value of wetlands and the laying down of social memories of place. -

090109 EPRA PROJECT River

RIVERSIDE MASTER PLAN REVIEW/2008 Prepared for East Perth Redevelopment Authority August 2008 Riverside Master Plan Review / 1 CONSULTANT TEAM This document has been prepared by HASSELL Ltd on behalf of the East Perth Redevelopment Authority. HASSELL Town Planning HASSELL Urban Design HASSELL Architecture HASSELL Landscape HASSELL Project Management NS Projects Environmental Syrinx Environmental Property Consultant Colliers International Economic Development Pracsys Sustainability URS Heritage Palassis Architects Traffic Engineers SKM Quantity Surveyor Ralph Beattie Bosworth Riverside Master Plan Review / 2 PREPARED BY Ken Maher Peter Lee Chris Melsom Denise Morgan Gary McCullough Andrew Lefort Cressida Beale Andrew Nugent Amber Hadley Riverside Master Plan Review / 3 CONTENT Executive Summary 8 1 Introduction 12 2 2004 Master Plan Vision and Objectives 14 2.1 Riverside Master Plan Update 16 2.2 Community Consultation 16 3 Riverside Master Plan Review 2008 17 3.1 Built Form 17 3.2 Streetscape and Public Realm 18 3.3 Density and Scale 18 3.4 Traffic 19 4 Key Influences 23 4.1 Urban Context 23 4.2 Landscape and Urban Form 25 4.3 Sustainability 27 4.3.1 Effective Sustainable Urban Place Making 27 4.3.2 Reduced Climate Change Impact 27 4.3.3 Strengthen and Enhance Community Wellbeing 27 4.3.4 Enhancement of Ecological Value 28 4.3.5 Sustainable Resource Use 28 4.3.6 Vital Economic Development 28 4.3.7 Flexible Transport and Optimal Connectivity (Movement) 28 4.4 Market Conditions and Demographic Change 28 4.4.1 Demographic Change 29 4.4.2 -

Derbarl Yerrigan Mandoon Estate

Alan Muller Tides: Paintings and Drawings of Derbarl Yerrigan Swan River “Rivers are life. These paintings and drawings re-imagine the physical, historic and spiritual heart of Perth - Derbarl Yerrigan Swan River as the river and land of the Whadjuk Nyoongar people, before the foundation of Perth and English settlement in 1829.” Alan Muller, 2019 Artist talk 2.30 pm Saturday 5th May 2019, Linton & Kay Galleries, Mandoon Estate, 10 Harris Road, Caversham 6155 Upper Swan after Garling 1827 Acrylic on canvas 2019, 90 x 150 cm Based on a combination of two historic views painted on location by Frederick Garling in 1827, the work is of late summer with one side of the river as embankment and the other as flood plain. Rainfall in the past was much higher than it is now so there was a distinct seasonal enlargement of the river in winter and contraction during summer. Crossing the River at Matagarup after Garling 1827 Acrylic on canvas 2019, 50 x 100 cm Derbarl Yerrigan Swan River at East Perth is where a lot of change has occurred since English settlement in 1829. The series of small islands depicted here were dredged and a single Heirisson Island created by expanding one of the existing islands. A part of the river to the left was filled in. This section of the river had shallow waters that enabled the Whadjuk people to cross the river in knee and waist deep water. It was the main place that the river was crossed by the Whadjuk people. Today it is the site of the Causeway. -

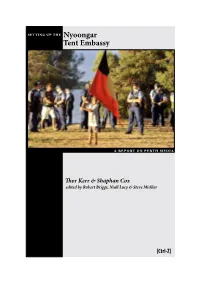

Setting up the Nyoongar Tent Embassy

Setting up the Nyoongar Tent Embassy A report on Perth Media Thor Kerr & Shaphan Cox edited by Robert Briggs, Niall Lucy & Steve Mickler [Ctrl-Z] SETTING UP THE NYOONGAR TENT EMBASSY • a report on perth media Thor Kerr & Shaphan Cox edited by Robert Briggs, Niall Lucy & Steve Mickler Ctrl-Z Press Perth 2013 [Ctrl-Z] www.ctrl-z.net.au © All rights reserved. This report is published with the assistance of the Centre for Culture & Technology (CCAT), Curtin University, and may be copied and distributed freely. ISBN 978-0-9875928-0-4 Thor Kerr is an Early Career Development Fellow in the School of Media, Culture & Creative Arts at Curtin University. His research focusses on media and public representation in negotiations of urban space. Shaphan Cox is an Early Career Development Fellow in Geography in the Department of Urban and Regional Planning at Curtin University. His research explores reconceptualisations of space through representation. • Robert Briggs is Coordinator of Mass Communication at Curtin University and co-editor with Niall Lucy of Ctrl-Z. His research has appeared in international journals of media, communication and cultural studies. Niall Lucy is Professor of Critical Theory at Curtin University and co- editor with Robert Briggs of Ctrl-Z. His books include A Derrida Dictionary, Pomo Oz: Fear and Loathing Downunder and (with Steve Mickler) The War on Democracy: Conservative Opinion in the Australian Press. Steve Mickler is Head of the School of Media, Culture & Creative Arts at Curtin University. He is the author of The Myth of Privilege: Aboriginal Status, Media Visions, Public Ideas. -

Noongar People, Noongar Land the Resilience of Aboriginal Culture in the South West of Western Australia

NOONGAR PEOPLE, NOONGAR LAND THE RESILIENCE OF ABORIGINAL CULTURE IN THE SOUTH WEST OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA NOONGAR PEOPLE, NOONGAR LAND THE RESILIENCE OF ABORIGINAL CULTURE IN THE SOUTH WEST OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA Kingsley Palmer First published in 2016 by AIATSIS Research Publications Copyright © South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council 2016 All rights reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (the Act), no part of this paper may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Act also allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this paper, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied or distributed digitally by any educational institution for its educational purposes, provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) GPO Box 553, Canberra ACT 2601 Phone: (61 2) 6246 1111 Fax: (61 2) 6261 4285 Email: [email protected] Web: www.aiatsis.gov.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Creator: Palmer, Kingsley, 1946- author. Title: Noongar land, Noongar people: the resilience of Aboriginal culture in the South West of Western Australia / Kingsley Palmer. ISBN: 9781922102294 (paperback) ISBN: 9781922102478 (ebook: pdf) ISBN: 9781922102485 (ebook: epub) Subjects: Noongar (Australian people)—History. Noongar (Australian people)—Land tenure.