© Copyright by Hyeok Lee May, 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Halle, the City of Music a Journey Through the History of Music

HALLE, THE CITY OF MUSIC A JOURNEY THROUGH THE HISTORY OF MUSIC 8 WC 9 Wardrobe Ticket office Tour 1 2 7 6 5 4 3 EXHIBITION IN WILHELM FRIEDEMANN BACH HOUSE Wilhelm Friedemann Bach House at Grosse Klausstrasse 12 is one of the most important Renaissance houses in the city of Halle and was formerly the place of residence of Johann Sebastian Bach’s eldest son. An extension built in 1835 houses on its first floor an exhibition which is well worth a visit: “Halle, the City of Music”. 1 Halle, the City of Music 5 Johann Friedrich Reichardt and Carl Loewe Halle has a rich musical history, traces of which are still Johann Friedrich Reichardt (1752–1814) is known as a partially visible today. Minnesingers and wandering musicographer, composer and the publisher of numerous musicians visited Giebichenstein Castle back in the lieder. He moved to Giebichenstein near Halle in 1794. Middle Ages. The Moritzburg and later the Neue On his estate, which was viewed as the centre of Residenz court under Cardinal Albrecht von Brandenburg Romanticism, he received numerous famous figures reached its heyday during the Renaissance. The city’s including Ludwig Tieck, Clemens Brentano, Novalis, three ancient churches – Marktkirche, St. Ulrich and St. Joseph von Eichendorff and Johann Wolfgang von Moritz – have always played an important role in Goethe. He organised musical performances at his home musical culture. Germany’s oldest boys’ choir, the in which his musically gifted daughters and the young Stadtsingechor, sang here. With the founding of Halle Carl Loewe took part. University in 1694, the middle classes began to develop Carl Loewe (1796–1869), born in Löbejün, spent his and with them, a middle-class musical culture. -

Zachows Kantaten

Einleitung Die vorliegenden Studien verfolgen das Ziel, die Quellen der Vokalwerke des Hall eschen Lehrmeisters Händels, Friedrich Wilhelm Zachow (1663-1712), zu erforschen, kompositions-, gattungs-, stilgeschichtliche Aspekte und stilbildende Elemente seiner erhaltenen Kompositionen zu untersuchen und kritisch zu besprechen. Es ist ein Ver such, zu einem besseren Verständnis der Kirchenmusik Zachows zu kommen und den bislang im wesentlichen nur generalisierten Stellenwert dieses wichtigen mittel deutschen Komponisten aus der Spätbarockzeit wissenschaftlich erneut zu durchden ken und herauszuarbeiten. Ich gehe davon aus, daß nach den beiden - traditionell als größte - anerkann ten Bachschen Vorgängern, Dietrich Buxtehude (1637-1707) und Johann Pachelbel (1653-1706), der in seiner besten Schaffenskraft gestorbene F.W. Zachow, Organist und Musikdirektor der Marienkirche zu Halle, als eine der interessantesten Persön lichkeiten aus der Zeit zwischen Heinrich Schütz und Georg Friedrich Händel bzw. Johann Sebastian Bach erscheint. Inwieweit konnte Zachow mit seiner „staerksten Vollstimmigkeit“ im Zeitraum von 1684 bis 1712 in Mitteldeutschland als ein Vorbild auch fuer denjuengen Bach auf dem Gebiet der Tonkunst, bzw. des stilistischen Ex- perimentierens dienen? Aufgrund seiner pädagogischen Rolle im Leben des jungen G. F. Händel ist dieser deutsche Komponist weltbekannt geworden. Es wäre viel zu einseitig und nicht ob jektiv genug, wollte man die musikgeschichtliche Bedeutung Zachows nur dadurch erklären und ausschließlich auf die Lehrtätigkeit beschränken: Der Meister war vor allem ein Tonkünstler auf dem Gebiet der evangelischen Kirchenmusik, und seine selbständige Bedeutung liegt in seinen Vokal- und Instrumentalwerken. Zachows Werke können auch zu heutiger Zeit in den Festgottesdiensten und Konzertprogram men aufgeführt werden. Händels Lehrmeister Zachow gehört auch zu den wichtigsten und im geschichtli chen Sinne bedeutendsten Vorgängern J. -

Pdf-Dokument

MUSIK - CDs CD.Sbo 2 / Haen HÄNDEL Händel, Georg Friedrich: Arcadian duets / Georg Friedrich Händel. Natalie Dessay ; Gens, Veronique …[s.l.] : Erato Disques, 2018. – 2 CDs Interpr.: Dessay, Natalie ; Veronique Gens CD. Sbo 2 / Haen HÄNDEL Händel, Georg Friedrich: Cembalosuiten (1720) Nr. 1 – 8 / Georg Friedrich Händel. Laurence Cummings.- [s.l.] : Somm, 2017. – 2 CDs Interpr.: Cummings, Laurence ; London Handel Orchestre CD. Sbo 2 / Haen HÄNDEL Händel, Georg Friedrich: Cembalowerke /Georg Friedrich Händel. Philippe Grisvard ; William Babell ; Friedrich Wilhelm Zachow … [s.l.] : audax, 2017.- Interpr.: Grisvard, Philippe ; Babell, William ; Zachow, Friedrich Wilhelm CD. Sbs 2 / Haen Händel Händel, Georg Friedrich: Arien / Georg Friedrich Händel. Bernadette Greevy ; Joan Sutherland … [s.l.] : Decca, 2017.- 2 CDs Interpr.: Greevy, Bernadette ; Sutherland, Joan CD. Sbs 2 / Haen Händel Händel, Georg Friedrich: Silla / Georg Friedrich Händel. James Bowman ; Simon Baker… [s.l.] : Somm, 2017.- 2 CDs Interpr.: Bowman, James ; Baker, Simon CD. Sbs 2 /Haen Händel Händel, Georg Friedrich: Instrumentalmusiken aus Opern & Oratorien / Georg Friedrich Händel. London Handel Players [s.l.] : Somm, 2017.- 1 CD Interpr.: London Handel Players 1 CD.Sbq 3 / Haen HÄNDEL Händel, Georg Friedrich: Aci, Galatea e Polifemo : Serenata. Napoli, 1708 / Handel. Roberta Invernizzi ... La Risonanza. Fabio Bonizzoni. - San Lorenzo de El Escorial : note 1 music, 2013. - 2 CDs + Beih. Interpr.: Bonizzoni, Fabio [Dir.] ; Invernizzi, Roberta ; La Risonanza CD.Sbs 2 / Haen HÄNDEL Händel, Georg Friedrich: Alessandro : live recorded at Badisches Staatstheater Karlsruhe / G. F. Handel. Lawrence Zazzo ... Deutsche Händel-Solisten on period instruments. Michael Form. - [S.l.] : note 1 music, 2012. - 3 CDs + Beih. Interpr.: Form, Michael; Zazzo, Lawrence; Deutsche Händel-Solisten CD.Sbs 2 / Haen HÄNDEL Händel, Georg Friedrich: Alessandro / Handel. -

Download Booklet

The Harmonious Thuringian Toccata in E minor, BWV 914 Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) 1. Toccata 4.18 2. Fugue 3.03 Suite VIII in G major Johann Caspar Ferdinand Fischer (1656–1746) 3. Prelude 2.21 4. Chaconne 3.47 5. Prelude in D minor Louis Marchand (1669–1732) 2.56 6. Passacaglia in D minor Johann Philipp Krieger (1649–1725) 11.01 7. Fantasia in G minor, BWV 917 Johann Sebastian Bach 2.22 8. Ich dich hab ich gehoffet Herr Johann Krieger (1651–1735) 3.30 9. Allemande in descessum Christian Ritter (1645 or 1650–1717) Caroli xi Regis Sveciae 4.50 Prelude and Fugue Johann Christoph Bach (1642–1703) in E flat major, BWV Anh.177 10. Prelude 1.49 11. Fugue 3.05 12. Fugue in C major Anon: attrib. Johann Pachelbel (1653–1706) 1.57 13. Capriccio Cromatico overo Tarquinio Merula (1594 or 1595–1665) Capriccio ... per le semi tuoni 4.02 14. Prelude in A major, BWV 896 Johann Sebastian Bach 0.50 15. Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland Friedrich Wilhelm Zachow (1663–1712) 2.55 16. Prelude Johann Kuhnau (1660–1722) 1.26 Suite No. 5 in E major, HWV 430 George Frideric Handel (1685–1759) 15.13 17. Prelude 2.09 18. Allemande 5.28 19. Courante 2.30 20. Air and Variations (‘Harmonious Blacksmith’) 4.59 Total playing time: 70.26 TERENCE CHARLSTON, harpsichord The Harmonious Thuringian A recording of late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century keyboard music, associated with the early years of Bach and Handel, performed on a reconstruction of a surviving German harpsichord of that period. -

HANDEL EDITION Liner Notes & Sung Texts

HANDEL EDITION Liner notes & sung texts (p. 40 – p. 97) LINER NOTES CD1 WATER MUSIC and in the fashionable country dance – and added splendid A king does not amuse himself alone highlights to the whole with horns (“French horns”, a novelty in On the evening of July 17, 1717, King George I of England England) and trumpets. Not only King George was enthusiastic boarded the royal barge at Whitehall in the company of a select about it. Striking proof of the popularity of the Water Music is group of ladies and was rowed up the Thames as far as Chelsea, the fact that pieces from it very soon found their way to the where Lady Catherine Jones was expecting him for supper. The concert platforms and into London's theatres; some were even river teemed with boats and barges, as the Daily Courant under laid with texts, two were used in Polly, the sequel to the announced two days later, for everybody who was anybody in legendary 'Beggar’s Opera by John Gay and John Christopher London wanted to accompany the king on this pleasure trip. A Pepusch and one was included in The English Dancing Master by special attraction was provided by a barge of the City Company, John Playford, a famous; often republished collection of popular on which some fifty musicians performed music composed dances. The “Minuet for the French Horn” and the ''Trumpet especially for the occasion; the king liked it so much that he had Minuet” enjoyed particular popularity. They were also the first it repeated twice. -

The Spread of “Tonal Form” : Music in the Seventeenth and Eighteent

The Spread Of “Tonal Form” : Music In The Seventeenth And Eighteent... http://www.oxfordwesternmusic.com/view/Volume2/actrade-9780195... Oxford History of Western Music: Richard Taruskin See also from Grove Music Online Alessandro Marcello Antonio Vivaldi Ritornello Henry Purcell THE SPREAD OF “TONAL FORM” Chapter: CHAPTER 5 The Italian Concerto Style and the Rise of Tonality-driven Form Source: MUSIC IN THE SEVENTEENTH AND EIGHTEENTH CENTURIES Author(s): Richard Taruskin Having characterized the sequence-and-cadence model as a norm that would usher in an era of “common practice,” we need to justify that remark by demonstrating its chronological and geographical spread. The chronological demonstration will emerge naturally enough in the course of the following chapters, but just to show how pervasive the model became within the sphere of Italian instrumental music, and how quickly it spread, we can sneak a peek at a concerto by a member of the generation immediately following Corelli’s. Alessandro Marcello (1669–1747) was a Venetian nobleman who practiced music as a dilettante —a “delighter” in the art—rather than one who pursued it for a living. His work was on a fully professional level, however, and achieved wide circulation in print. (His younger brother Benedetto, even more famous and accomplished as a composer, was also more prominent as a Venetian citizen, occupying high positions in government and diplomacy.) Marcello, like Corelli before him, was a member of the Arcadian Academy, and maintained a famous salon, a weekly gathering of artist-dilettantes where he had his music performed for his own and his company’s enjoyment. -

George Frideric Handel from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

George Frideric Handel From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Born Georg Friedrich Händel 23 February 1685 (O.S.) Halle, Duchy of Magdeburg, Holy Roman Empire Died 14 April 1759 (aged 74) London, England George Frideric (or Frederick) Handel (/ˈhændəl/; born Georg Friedrich Händel, German pronunciation: *ˈhɛndəl]; February 1685 (O.S.) [(N.S.) 5 March] – 14 April 1759) was a German-born, British Baroque composer who spent the bulk of his career in London, becoming well known for his operas, oratorios, anthems and organ concertos. Born in a family indifferent to music, Handel received critical training in Halle, Hamburg and Italy before settling in London (1712), and became a naturalized British subject in 1727. He was strongly influenced both by the great composers of the Italian Baroque and the middle-German polyphonic choral tradition. Within fifteen years, Handel had started three commercial opera companies to supply the English nobility with Italian opera. Musicologist Winton Dean writes that his operas show that "Handel was not only a great composer; he was a dramatic genius of the first order." As Alexander's Feast (1736) was well received, Handel made a transition to English choral works. After his success with Messiah (1742) he never performed an Italian opera again. Almost blind, and having lived in England for nearly fifty years, he died in 1759, a respected and rich man. His funeral was given full state honours, and he was buried in Westminster Abbey. Born the same year as Johann Sebastian Bach and Domenico Scarlatti, Handel is regarded as one of the greatest composers of the Baroque era, with works such as Water Music, Music for the Royal Fireworks and Messiah remaining steadfastly popular. -

Blacksburg Master Chorale Messiah Sunday, December 15, 2019, 4 PM

Advance Program Notes Blacksburg Master Chorale Messiah Sunday, December 15, 2019, 4 PM These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. Blacksburg Master Chorale Handel’s Messiah Meredith Bowen, guest conductor Melissa Heath, soprano Charles Humphries, countertenor Brian Thorsett, tenor David Newman, baritone Program Notes Good evening and welcome to the 2019 edition of Blacksburg Master Chorale’s performance of Handel’s Messiah. I’m thrilled to be invited to conduct this ensemble and orchestra in Dwight’s absence. It has been an honor to work with these fine folks over the last seven weeks. I’m a huge Baroque choral nerd, and this experience has been very rewarding. Let’s take a journey back to the days when Louis XIV moved to Versailles, the city of Philadelphia was founded by William Penn, Isaac Newton was writing about gravity, and James Stuart was crowned King James II. This is the age in which our composer is born. George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) was a German composer who wrote Italian opera in England. Handel was born in Halle, Germany, a small city north of Leipzig where he studied music theory, organ, harpsichord, and violin with Friedrich Wilhelm Zachow. He was appointed organist at a Calvinist Cathedral in Halle when he was 17. He took a grand tour of Italy when he was 21, a 17th- and 18th- century tradition for upper-class young, wealthy European men of rank. -

Historic Organs of Belgium May 15-26, 2018 12 Days with J

historic organs of BELGIUM May 15-26, 2018 12 Days with J. Michael Barone historic organs of GERMANY May 22-June 4, 2019 14 Days with J. Michael Barone www.americanpublicmedia.org www.pipedreams.org National broadcasts of Pipedreams are made possible with funding from Mr. & Mrs. Wesley C. Dudley, grants from Walter McCarthy, Clara Ueland, and the Greystone Foundation, the Art and Martha Kaemmer Fund of the HRK Foundation, and Jan Kirchner on behalf of her family foun- dation, by the contributions of listeners to American Public Media stations nationwide, and by the thirty member organizations of the Associated Pipe Organ Builders of America, APOBA, represent- ing the designers and creators of pipe organs heard throughout the country and around the world, with information at www.apoba.com. See and hear Pipedreams on the Internet 24-7 at www.pipedreams.org. A complete booklet pdf with the tour itinerary can be accessed online at www.pipedreams.org/tour Table of Contents Welcome Letter Page 2 Bios of Hosts and Organists Page 3-7 The Thuringian Organ Scene Page 8-9 Alphabetical List of Organ Builders Page 10-15 Organ Observations Page 16-18 Tour Itinerary Page 19-22 Tour Members Playing the Organs Page 23 Organ Sites Page 24-116 Rooming List Page 117 Traveler Profiles Page 118-122 Hotel List Page 123-124 Map Inside Back Cover Thanks to the following people for their valuable assistance in creating this tour: Tim Schmutzler Valerie Bartl, Cynthia Jorgenson, Kristin Sullivan, Janet Tollund, and Tom Witt of Accolades International Tours for the Arts in Minneapolis. -

J. S. Bach Und Die Italienische Oper

J. S. Bach und die italienische Oper Drammi per musica für das kurfürstlich-sächsische und polnische Königshaus zwischen 1733 und 1736 Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades des Doctor scientiae musicae im Fach Musikwissenschaft an der Hochschule für Musik und Theater Hamburg vorgelegt von: Jens Wessel Hamburg 2015 Disputation am 23. März 2016 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Hochstein Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Sven Hiemke Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einleitung ............................................................................................................................. 7 1.1. Aufbau und Struktur der Arbeit ........................................................................................ 10 1.2. Form der Kantate – Einfluss der madrigalischen Dichtung – Definition Dramma per musica .................................................................................................................................... 10 1.3. Terminologie weltlicher Vokalwerke – Das Dramma per musica bei Bach ..................... 15 1.4. Bachs Berührungspunkte mit der Oper – Entwicklung seiner Vokalkompositionen ........ 19 1.4.1. Lüneburg (Hamburg, Celle) (1700–1702/1703) – Weimar I (1703) – Arnstadt (1703– 1707) – Mühlhausen (1707–1708) ......................................................................................... 19 1.4.2. Weimar II (1708–1717) ................................................................................................ 21 1.4.3. Köthen (1717–1723) ................................................................................................... -

DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY Handel and His Accompanied Recitatives

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Handel and his accompanied recitatives Gorry, Liam Award date: 2012 Awarding institution: Queen's University Belfast Link to publication Terms of use All those accessing thesis content in Queen’s University Belfast Research Portal are subject to the following terms and conditions of use • Copyright is subject to the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988, or as modified by any successor legislation • Copyright and moral rights for thesis content are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners • A copy of a thesis may be downloaded for personal non-commercial research/study without the need for permission or charge • Distribution or reproduction of thesis content in any format is not permitted without the permission of the copyright holder • When citing this work, full bibliographic details should be supplied, including the author, title, awarding institution and date of thesis Take down policy A thesis can be removed from the Research Portal if there has been a breach of copyright, or a similarly robust reason. If you believe this document breaches copyright, or there is sufficient cause to take down, please contact us, citing details. Email: [email protected] Supplementary materials Where possible, we endeavour to provide supplementary materials to theses. This may include video, audio and other types of files. We endeavour to capture all content and upload as part of the Pure record for each thesis. Note, it may not be possible in all instances to convert analogue formats to usable digital formats for some supplementary materials. We exercise best efforts on our behalf and, in such instances, encourage the individual to consult the physical thesis for further information. -

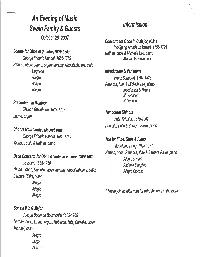

An Evening of Music

An Evening of Music "'- Intermission Swain Family & Guests October 26, 2007 Concerto for Oboe in C Major, K.314 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, 1756-1791 Sonata for Oboe in g minor, HWV 364a Nathan, oboe & Michelle Lee, piano George Frideric Handel, 1685-1759 Allegro, 1st movement Nathan, oboe; Laurie, organ; Jeremy Woolstenhulme, cello Larghetto Introduction & Variations Allegro · Franz Schubert, 1797-1828 Adagio Rebecca, flute & Michelle Lee, piano Allegro Introduction & Theme :fd Variation 1 Praeludium in f# minor 5 h Variation Dietrich Buxtehude, 1637-1707 Tambourin Chinois Laurie, organ Fritz Kriesler, 1875-1962 Danielle, violin & Barbara Riske, piano Chorus from 11Judas Maccabaeus" George Frideric Handel, 1685-1759 Trio for Flute, Oboe & Piano Michael, cello & Nathan, piano Madeleine Dring, 1923-1977 Nathan, oboe; Rebecca, flute & Barbara Riske, piano Bach Concerto for Oboe & Violin in c minor, CWV 1060 Allegro con brio JS Bach, 1685-1750 Andante Semplice Nathan, oboe; Danielle, violin; Jeremy Woolstenhulme, cello; Allegro Giocoso Barbara Riske, piano Allegro Adagio *Please join us afterward for refreshments in the lobby Allegro Sonata II in G Major Joseph Bodin de Boismortier 1682-1765 Nathan, oboe; Laurie, organ; Rebecca, flute; Danielle, violin; Michael, cello Allegro Largo Allegro George Frideric Handel, 1685-1759 Perhaps the single word that Johann Sebastian Bach, 1685-1750 Bach is considered by many best describes the life and music of George Frideric Handel is "cosmopolitan." to have been the greatest composer in the history of western music. He was the He was a German composer, trained in Italy, who spent most of his life in youngest child of Johann Ambrosius Bach, an organist at St.