Download Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Dream Job: Next Exit?'

Understanding Bach, 9, 9–24 © Bach Network UK 2014 ‘Dream Job: Next Exit?’: A Comparative Examination of Selected Career Choices by J. S. Bach and J. F. Fasch BARBARA M. REUL Much has been written about J. S. Bach’s climb up the career ladder from church musician and Kapellmeister in Thuringia to securing the prestigious Thomaskantorat in Leipzig.1 Why was the latter position so attractive to Bach and ‘with him the highest-ranking German Kapellmeister of his generation (Telemann and Graupner)’? After all, had their application been successful ‘these directors of famous court orchestras [would have been required to] end their working relationships with professional musicians [take up employment] at a civic school for boys and [wear] “a dusty Cantor frock”’, as Michael Maul noted recently.2 There was another important German-born contemporary of J. S. Bach, who had made the town’s shortlist in July 1722—Johann Friedrich Fasch (1688–1758). Like Georg Philipp Telemann (1681–1767), civic music director of Hamburg, and Christoph Graupner (1683–1760), Kapellmeister at the court of Hessen-Darmstadt, Fasch eventually withdrew his application, in favour of continuing as the newly- appointed Kapellmeister of Anhalt-Zerbst. In contrast, Bach, who was based in nearby Anhalt-Köthen, had apparently shown no interest in this particular vacancy across the river Elbe. In this article I will assess the two composers’ positions at three points in their professional careers: in 1710, when Fasch left Leipzig and went in search of a career, while Bach settled down in Weimar; in 1722, when the position of Thomaskantor became vacant, and both Fasch and Bach were potential candidates to replace Johann Kuhnau; and in 1730, when they were forced to re-evaluate their respective long-term career choices. -

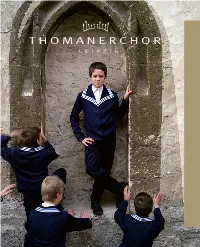

T H O M a N E R C H

Thomanerchor LeIPZIG DerThomaner chor Der Thomaner chor ts n te on C F o able T Ta b l e o f c o n T e n T s Greeting from “Thomaskantor” Biller (Cantor of the St Thomas Boys Choir) ......................... 04 The “Thomanerchor Leipzig” St Thomas Boys Choir Now Performing: The Thomanerchor Leipzig ............................................................................. 06 Musical Presence in Historical Places ........................................................................................ 07 The Thomaner: Choir and School, a Tradition of Unity for 800 Years .......................................... 08 The Alumnat – a World of Its Own .............................................................................................. 09 “Keyboard Polisher”, or Responsibility in Detail ........................................................................ 10 “Once a Thomaner, always a Thomaner” ................................................................................... 11 Soli Deo Gloria .......................................................................................................................... 12 Everyday Life in the Choir: Singing Is “Only” a Part ................................................................... 13 A Brief History of the St Thomas Boys Choir ............................................................................... 14 Leisure Time Always on the Move .................................................................................................................. 16 ... By the Way -

Halle, the City of Music a Journey Through the History of Music

HALLE, THE CITY OF MUSIC A JOURNEY THROUGH THE HISTORY OF MUSIC 8 WC 9 Wardrobe Ticket office Tour 1 2 7 6 5 4 3 EXHIBITION IN WILHELM FRIEDEMANN BACH HOUSE Wilhelm Friedemann Bach House at Grosse Klausstrasse 12 is one of the most important Renaissance houses in the city of Halle and was formerly the place of residence of Johann Sebastian Bach’s eldest son. An extension built in 1835 houses on its first floor an exhibition which is well worth a visit: “Halle, the City of Music”. 1 Halle, the City of Music 5 Johann Friedrich Reichardt and Carl Loewe Halle has a rich musical history, traces of which are still Johann Friedrich Reichardt (1752–1814) is known as a partially visible today. Minnesingers and wandering musicographer, composer and the publisher of numerous musicians visited Giebichenstein Castle back in the lieder. He moved to Giebichenstein near Halle in 1794. Middle Ages. The Moritzburg and later the Neue On his estate, which was viewed as the centre of Residenz court under Cardinal Albrecht von Brandenburg Romanticism, he received numerous famous figures reached its heyday during the Renaissance. The city’s including Ludwig Tieck, Clemens Brentano, Novalis, three ancient churches – Marktkirche, St. Ulrich and St. Joseph von Eichendorff and Johann Wolfgang von Moritz – have always played an important role in Goethe. He organised musical performances at his home musical culture. Germany’s oldest boys’ choir, the in which his musically gifted daughters and the young Stadtsingechor, sang here. With the founding of Halle Carl Loewe took part. University in 1694, the middle classes began to develop Carl Loewe (1796–1869), born in Löbejün, spent his and with them, a middle-class musical culture. -

Gaspard Le Roux 1660-1707 Pièces De Clavessin (1705)

Gaspard Complete HarpsichordLe Roux Music Pieter-Jan Belder Siebe Henstra Gaspard le Roux 1660-1707 Pièces de Clavessin (1705) Suite in D minor/major Suite in F major 39. Sarabande (en douze couplets) 13’00 Pieter-Jan Belder harpsichord I 1. Prélude 0’46 21. Prélude 1’25 40. Menuet 1’01 (Solo on 16-26) 2. Allemande, “la Vauvert” 4’25 22. Allemande grave 3’05 41. Gigue (pour deux Clavecins) 1’52 Siebe Henstra harpsichord II 3. Courante 1’17 23. Courante 1’27 42. Courante (avec sa contre partie) 1’31 (Solo on harpsichord I, on 33-42 ) 4. Sarabande grave 2’05 24. Chaconne 4’03 5. Menuet 1’20 25. Menuet & 2 Doubles Suite in A minor/major Harpsichord I: Titus Crijnen after 6. Passepied 0’40 du Menuet 1’55 (solo version) Ruckers 1624, Sabiñan 2014 7. Courante luthée 1’55 26. Passepied 0’54 43. Prélude 0’50 Harpsichord II: Titus Crijnen after 8. Allemande grave, 27. Allemande 1’54 44. Allemande “l’Incomparable” 2’21 Blanchet 1731, Sabiñan 2013 “la Lorenzany” 3’28 45. Courante 1’29 9. Courante 1’28 Suite in F-sharp minor 46. Sarabande 2’02 10. Sarabande gaye 2’51 28. Allemande gaye 1’10 47. Sarabande en Rondeau 2’15 11. Gavotte 1’09 29. Courante 1’27 48. Gavotte 1’05 30. Double de la Courante 1’32 49. Menuet & double du Menuet 1’01 Suite in A minor/major 31. Sarabande grave en Rondeau 2’25 50. Second Menuet 0’32 12. Prélude 0’50 32. -

Ons-Tafelmusik.Pdf

CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS AT PENN STATE ONSTAGE Don Lee, The Banff Centre Banff The Don Lee, Today’s performance is sponsored by Gay D. Dunne and James H. Dunne COMMUNITY ADVISORY COUNCIL The Community Advisory Council is dedicated to strengthening the relationship between the Center for the Performing Arts and the community. Council members participate in a range of activities in support of this objective. Nancy VanLandingham, chair Mary Ellen Litzinger Lam Hood, vice chair Bonnie Marshall Pieter Ouwehand William Asbury Melinda Stearns Patricia Best Susan Steinberg Lynn Sidehamer Brown Lillian Upcraft Philip Burlingame Pat Williams Alfred Jones Jr. Nina Woskob Deb Latta Eileen Leibowitz student representative Ellie Lewis Jesse Scott Christine Lichtig CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS AT PENN STATE presents Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra Jeanne Lamon, director The Galileo Project: Music of the Spheres Conceived, programmed, and scripted by Alison Mackay Glenn Davidson, production designer Marshall Pynkoski, stage director John Percy, astronomical consultant Shaun Smyth, narrator 7:30 p.m. Wednesday, November 5, 2014 Schwab Auditorium The performance includes one intermission. This presentation is a component of the Center for the Performing Arts Classical Music Project. With support from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the proj- ect provides opportunities to engage students, faculty, and the community with classical music artists and programs. Marica Tacconi, Penn State professor of musicology and Carrie Jackson, Penn State associate professor of German and linguistics, provide faculty leadership for the curriculum and academic components of the grant project. sponsors Gay D. Dunne and James H. Dunne support provided by Nina C. Brown Endowment media sponsor WPSU The Center for the Performing Arts at Penn State receives state arts funding support through a grant from the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, a state agency funded by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, and the National Endowment for the Arts, a federal agency. -

Breathtaking-Program-Notes

PROGRAM NOTES In the 16th and 17th centuries, the cornetto was fabled for its remarkable ability to imitate the human voice. This concert is a celebration of the affinity of the cornetto and the human voice—an exploration of how they combine, converse, and complement each other, whether responding in the manner of a dialogue, or entwining as two equal partners in a musical texture. The cornetto’s bright timbre, its agility, expressive range, dynamic flexibility, and its affinity for crisp articulation seem to mimic a player speaking through his instrument. Our program, which puts voice and cornetto center stage, is called “breathtaking” because both of them make music with the breath, and because we hope the uncanny imitation will take the listener’s breath away. The Bolognese organist Maurizio Cazzati was an important, though controversial and sometimes polemical, figure in the musical life of his city. When he was appointed to the post of maestro di cappella at the basilica of San Petronio in the 1650s, he undertook a sweeping and brutal reform of the chapel, firing en masse all of the cornettists and trombonists, many of whom had given thirty or forty years of faithful service, and replacing them with violinists and cellists. He was able, however, to attract excellent singers as well as string players to the basilica. His Regina coeli, from a collection of Marian antiphons published in 1667, alternates arioso-like sections with expressive accompanied recitatives, and demonstrates a virtuosity of vocal writing that is nearly instrumental in character. We could almost say that the imitation of the voice by the cornetto and the violin alternates with an imitation of instruments by the voice. -

Harpsichord Suite in a Minor by Élisabeth Jacquet De La Guerre

Harpsichord Suite in A Minor by Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre Arranged for Solo Guitar by David Sewell A Research Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Approved November 2019 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Frank Koonce, Chair Catalin Rotaru Kotoka Suzuki ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY December 2019 ABSTRACT Transcriptions and arrangements of works originally written for other instruments have greatly expanded the guitar’s repertoire. This project focuses on a new arrangement of the Suite in A Minor by Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre (1665–1729), which originally was composed for harpsichord. The author chose this work because the repertoire for the guitar is critically lacking in examples of French Baroque harpsichord music and also of works by female composers. The suite includes an unmeasured harpsichord prelude––a genre that, to the author’s knowledge, has not been arranged for the modern six-string guitar. This project also contains a brief account of Jacquet de la Guerre’s life, discusses the genre of unmeasured harpsichord preludes, and provides an overview of compositional aspects of the suite. Furthermore, it includes the arrangement methodology, which shows the process of creating an idiomatic arrangement from harpsichord to solo guitar while trying to preserve the integrity of the original work. A summary of the changes in the current arrangement is presented in Appendix B. i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my great appreciation to Professor Frank Koonce for his support and valuable advice during the development of this research, and also to the members of my committee, Professor Catalin Rotaru and Dr. -

Download Booklet

Johann Jacob Froberger (1616–1667) Complete Fantasias and Canzonas 6 Fantasias Libro Secondo (1649) 1 Fantasia I sopra∙VT∙RE∙MI∙FA∙SOL∙LA FbWV 2018:08 2 Fantasia II FbWV 202 3:49 3 Fantasia III FbWV 203 4:29 4 Fantasia IV sopra Sollare FbWV 204 3:40 5 Fantasia V FbWV 205 3:08 6 Fantasia VI FbWV 206 4:31 7 Fantasia FbWV 207 4:47 8 Fantaisie.Duo FbWV 208 2:31 6 Canzonas Libro Secondo (1649) 9 Canzon I FbWV 301 6:39 10 Canzon II FbWV 302 4:55 11 Canzon III FbWV 303 3:27 12 Canzon IV FbWV 304 5:54 13 Canzon V FbWV 305 2:34 14 Canzon VI FbWV 306 3:29 total duration 62:04 Terence Charlston, clavichord first recording on clavichord Froberger : Complete Fantasias and Canzonas This unusual recording project marks the happy confluence of idea and opportunity. Froberger’s fantasias and canzonas are amongst his most beautifully crafted yet most neglected works. They survive together with toccatas and partitas in a meticulously written autograph manuscript, the Libro Secondo, dated 19 September 1649 (A-Wn Mus.Hs.18706). They have been selectively performed and recorded in recent times on organ and harpsichord, but hardly at all on the clavichord. A recording on clavichord was clearly needed but until recently I had not come across an instrument which I felt was equal to the task. Then, in 2018, quite by chance, I discovered the clavichord used in these performances. It is a reconstruction of a south German clavichord now in the Berlin Musical Instrument Museum (hereafter referred to by the catalogue number of the original, MIM 2160) and was made by Andreas Hermert in 2009. -

Schwemmer,H. Deus in Nomine a 12 P+St

UUB vmhs035,002 Deus in nomine tuo salvum me fac a 12 Heinrich Schwemmer 1621-1696 Dübensammlung 5 voci: 2 viol: 2 Corn è 3 Trombone di Heinrico Schwemmer Canto primo C1 & C „ „ Canto 2do C1 & C „ „ Alto C3 V C „ „ Tenore C4 V C „ „ Basso C4 ? C „ „ Violino primo G2 & C „ „ Violino 2do G2 & C „ „ Sonata œ œ œ œ œ Cornetto 1 œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ ˙ G2 & C ‰ J ‰ J Cornetto 2 œ œ. œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ G2 & C œ œ œ ‰ J J ‰ J œ #œ Trom 1 œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ. œ œ. œ ˙ #˙ C3 V C ‰ J #œ ‰ J J J Tromb:2 j . j C4 C ‰ œ œ ‰ œ œ. œ bœ V œ œ œ œ J œ J J œ. œ œ ˙ Tromb. 3. j j j œ œ F4 ? C œ œ ‰ ‰ j œ. œ ˙ #œ nœ bœ. œ œ œ œ. œ J ? œ œ œ C œ #œ œ nœ b˙ œ ˙ œ. J ˙ Heinrich Schwemmer (28 March 1621 – 31 May 1696) was a German musicœ teacher and composer. He was born in Gumpertshausen bei Hallburg, Lower Franconia, and moved with his mother to Weimar after his father’s death in 1627, to get away from the Thirty Years War. After his mother's death in 1638, he moved to Coburg, then in 1641 to Nuremberg, when he remained for the rest of his life. -

Charles Dieupart Ruth Wilkinson Linda Kent PREMIER RECORDING

Music for the Countess of Sandwich Six Suites for Flûte du Voix and Harpsichord Charles Dieupart Ruth Wilkinson Linda Kent PREMIER RECORDING A rare opportunity to experience the unusual, haunting colours of the “voice flute”. Includes two suites copied by J.S. Bach. First release of the Linda Kent Ruth Wilkinson complete suites of Charles Dieupart. Six Suites for Flûte du Voix and Harpsichord (1701) by Charles Dieupart Music for the Countess of Sandwich P 1995 MOVE RECORDS Suitte 1 A major (13’35”) Suitte 4 e minor (12’23”) AUSTRALIA Siutte 2 D major (10’10”) Suitte 3 b minor (12’44”) Suitte 6 f minor (13’46”) Suitte 5 F major (14’19”) move.com.au harles Dieupart was of the 17th century for her health: a French violinist, it was possible that she became C harpsichordist and Dieupart’s harpsichord pupil composer who spent the last before returning to England. 40 years of his life in England. Two versions of the Suites He was known as Charles to his were published simultaneously contemporaries in England but about his final years. One story in Amsterdam by Estienne there is some evidence from letters claimed that Dieupart was on the Roger: one for solo harpsichord signed by Dieupart that he was known brink of going to the Indies to follow and the other with separate parts as Francois in his native France. He a surgeon who proposed using music for violin or flute with a continuo was active in the operatic world: as an anaesthetic for lithotomies. part for bass viol or theorbo and we learn from Sir John Hawkins Hawkins gives us the following figured bass. -

There Isn't a Piece That Doesn't Impress. This Is As

Also by Trio Settecento on Cedille Records An Italian Soujourn CDR 90000 099 “There isn’t a piece that doesn’t impress. This is as good a collection for a newcomer to the Baroque as it is for those who want to hear these works performed at a high level.” — Gramophone Producer: James Ginsburg Schmelzer) / Louis Begin, replica of 18th Century model (rest of program) Trio Settecento A German Bouquet Engineer: Bill Maylone Bass Viola da Gamba: William Turner, Art Direction: Adam Fleishman / 1 Johann Schop (d. 1667): Nobleman (1:56) bm Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) London, 1650 Fugue in G minor, BWV 1026 (3:54) www.adamfleishman.com 2 Johann Heinrich Schmelzer (c. 1620–1680) ’Cello: Unknown Tyrolean maker, 18th Cover Painting: Still Life with a Wan’li Sonata in D minor (5:49) Philipp Heinrich Erlebach (1657–1714) century (Piesendel) Sonata No. 3 in A Major (14:06) Vase of Flowers (oil on copper), Georg Muffat (1653–1704) Bosschaert, Ambrosius the Elder (1573- Viola da Gamba and ’Cello Bow: Julian Sonata in D major (11:33) bn I. Adagio—Allegro—Lento (2:35) 1621) / Private Collection / Johnny Van Clarke bo II. Allemande (2:19) 3 I. Adagio (2:34) Haeften Ltd., London / The Bridgeman bp III. Courante (1:33) Harpsichord: Willard Martin, Bethlehem, 4 II. Allegro—Adagio—Allegro—Adagio (8:59) Art Library bq IV. Sarabande (1:53) Pennsylvania, 1997. Single-manual Johann Philipp Krieger (1649–1725) br V. Ciaconne (3:42) Recorded June 16, 17, 19, 23, and 24, instrument after a concept by Marin Sonata in D Minor Op. -

Baroque and Classical Style in Selected Organ Works of The

BAROQUE AND CLASSICAL STYLE IN SELECTED ORGAN WORKS OF THE BACHSCHULE by DEAN B. McINTYRE, B.A., M.M. A DISSERTATION IN FINE ARTS Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Chairperson of the Committee Accepted Dearri of the Graduate jSchool December, 1998 © Copyright 1998 Dean B. Mclntyre ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful for the general guidance and specific suggestions offered by members of my dissertation advisory committee: Dr. Paul Cutter and Dr. Thomas Hughes (Music), Dr. John Stinespring (Art), and Dr. Daniel Nathan (Philosophy). Each offered assistance and insight from his own specific area as well as the general field of Fine Arts. I offer special thanks and appreciation to my committee chairperson Dr. Wayne Hobbs (Music), whose oversight and direction were invaluable. I must also acknowledge those individuals and publishers who have granted permission to include copyrighted musical materials in whole or in part: Concordia Publishing House, Lorenz Corporation, C. F. Peters Corporation, Oliver Ditson/Theodore Presser Company, Oxford University Press, Breitkopf & Hartel, and Dr. David Mulbury of the University of Cincinnati. A final offering of thanks goes to my wife, Karen, and our daughter, Noelle. Their unfailing patience and understanding were equalled by their continual spirit of encouragement. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii ABSTRACT ix LIST OF TABLES xi LIST OF FIGURES xii LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES xiii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS xvi CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 11. BAROQUE STYLE 12 Greneral Style Characteristics of the Late Baroque 13 Melody 15 Harmony 15 Rhythm 16 Form 17 Texture 18 Dynamics 19 J.