Full Paper(.Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Take Steps to Abolish Lakhanpur Toll Post

www.thenorthlines.com www.epaper.northlines.com 3 DAYS’ FORECAST JAMMU Date Min Temp Max Temp Weather 13-Sep 23.0 32.0 Partly cloudy sky 14-Sep 23.0 33.0 Partly cloudy sky 15-Sep 22.0 32.0 Partly cloudy sky 3 DAYS’ FORECAST SRINAGAR 13-Sep 13.0 29.0 Partly cloudy sky 14-Sep 14.0 27.0 Generally cloudy sky 15-Sep 13.0 25.0 Thunderstorm with rain Compensate Jammu Pradesh for northlinesSymposium organised by Northern the Holistic development key to biases in past: Harsh Command HQ transforming JK economy: Veeri A delegation of JKNPP led by Harsh North Tech Symposium showcase The Minister for Revenue, Relief & Dev Singh JKNPP Chairman and event was organised by Headquarters, Rehabilitation and Parliamentary Former Minister called uponUnion Northern Command at Udhampur on Affairs, Mr. Abdul Rehman Veeri Home Minister Raj Nath Singh at Sep 11, Sep 12, 2017. The event which today said that holistic development is 3 4 7 key for driving economy ... Jammu and submitted ... initially started as ... INSIDE Vol No: XXII Issue No. 218 13.09.2017 (Wednesday) Daily Jammu Tawi Price 3/- Pages-12 Regd. No. JK|306|2017-19 Take steps to abolish ‘Kashmir situation better but Centre to constitute expert Lakhanpur toll post: HM truce violations alarming’ group to study JK border agony ‘Pakistan doesn’t appear to be keen on improving ties with India’ NL CORRESPONDENT people living in the border Chamber demands deportation of Rohingyas JAMMU TAWI, SEPT 12 areas. The Centre is trying to NL CORRESPONDENT year 2016,” Rajnath said be constructed in the days to give equitable development as it defied the notion of abolish toll at Lakhanpur. -

Muslim Women's Pilgrimage to Mecca and Beyond

Muslim Women’s Pilgrimage to Mecca and Beyond This book investigates female Muslims pilgrimage practices and how these relate to women’s mobility, social relations, identities, and the power struc- tures that shape women’s lives. Bringing together scholars from different disciplines and regional expertise, it offers in-depth investigation of the gendered dimensions of Muslim pilgrimage and the life-worlds of female pilgrims. With a variety of case studies, the contributors explore the expe- riences of female pilgrims to Mecca and other pilgrimage sites, and how these are embedded in historical and current contexts of globalisation and transnational mobility. This volume will be relevant to a broad audience of researchers across pilgrimage, gender, religious, and Islamic studies. Marjo Buitelaar is an anthropologist and Professor of Contemporary Islam at the University of Groningen, The Netherlands. She is programme-leader of the research project ‘Modern Articulations of Pilgrimage to Mecca’, funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). Manja Stephan-Emmrich is Professor of Transregional Central Asian Stud- ies, with a special focus on Islam and migration, at the Institute for Asian and African Studies at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Germany, and a socio-cultural anthropologist. She is a Principal Investigator at the Berlin Graduate School Muslim Cultures and Societies (BGSMCS) and co-leader of the research project ‘Women’s Pathways to Professionalization in Mus- lim Asia. Reconfiguring religious knowledge, gender, and connectivity’, which is part of the Shaping Asia network initiative (2020–2023, funded by the German Research Foundation, DFG). Viola Thimm is Professorial Candidate (Habilitandin) at the Institute of Anthropology, University of Heidelberg, Germany. -

Modernity, Locality and the Performance of Emotion in Sufi Cults

EMBODYING CHARISMA Emerging often suddenly and unpredictably, living Sufi saints practising in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh are today shaping and reshaping a sacred landscape. By extending new Sufi brotherhoods and focused regional cults, they embody a lived sacred reality. This collection of essays from many of the subject’s leading researchers argues that the power of Sufi ritual derives not from beliefs as a set of abstracted ideas but rather from rituals as transformative and embodied aesthetic practices and ritual processes, Sufi cults reconstitute the sacred as a concrete emotional and as a dissenting tradition, they embody politically potent postcolonial counternarrative. The book therefore challenges previous opposites, up until now used as a tool for analysis, such as magic versus religion, ritual versus mystical belief, body versus mind and syncretic practice versus Islamic orthodoxy, by highlighting the connections between Sufi cosmologies, ethical ideas and bodily ritual practices. With its wide-ranging historical analysis as well as its contemporary research, this collection of case studies is an essential addition to courses on ritual and religion in sociology, anthropology and Islamic or South Asian studies. Its ethnographically rich and vividly written narratives reveal the important contributions that the analysis of Sufism can make to a wider theory of religious movements and charismatic ritual in the context of late twentieth-century modernity and postcoloniality. Pnina Werbner is Reader in Social Anthropology at Keele University. She has published on Sufism as a transnational cult and has a growing reputation among Islamic scholars for her work on the political imaginaries of British Islam. Helene Basu teaches Social Anthropology at the Institut für Ethnologie in Berlin. -

The Situation of Religious Minorities

writenet is a network of researchers and writers on human rights, forced migration, ethnic and political conflict WRITENET writenet is the resource base of practical management (uk) e-mail: [email protected] independent analysis PAKISTAN: THE SITUATION OF RELIGIOUS MINORITIES A Writenet Report by Shaun R. Gregory and Simon R. Valentine commissioned by United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Status Determination and Protection Information Section May 2009 Caveat: Writenet papers are prepared mainly on the basis of publicly available information, analysis and comment. All sources are cited. The papers are not, and do not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. The views expressed in the paper are those of the author and are not necessarily those of Writenet or UNHCR. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms ................................................................................................... i Executive Summary ................................................................................. ii 1 Introduction........................................................................................1 2 Background.........................................................................................4 3 Religious Minorities in Pakistan: Understanding the Context......6 3.1 The Constitutional-Legal Context..............................................................6 3.2 The Socio-Religious Context .......................................................................8 -

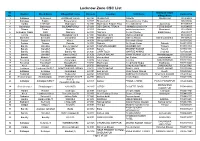

Lucknow Zone CSC List.Xlsx

Lucknow Zone CSC List Sl. Grampanchayat District Block Name Village/CSC name Pincode Location VLE Name Contact No No. Village Name 1 Sultanpur Sultanpur4 JAISINGHPUR(R) 228125 ISHAQPUR DINESH ISHAQPUR 730906408 2 Sultanpur Baldirai Bhawanighar 227815 Bhawanighar Sarvesh Kumar Yadav 896097886 3 Hardoi HARDOI1 Madhoganj 241301 Madhoganj Bilgram Road Devendra Singh Jujuvamau 912559307 4 Balrampur Balrampur BALRAMPUR(U) 271201 DEVI DAYAL TIRAHA HIMANSHU MISHRA TERHI BAZAR 912594555 5 Sitapur Sitapur Hargaon 261121 Hargaon ashok kumar singh Mumtazpur 919283496 6 Ambedkar Nagar Bhiti Naghara 224141 Naghara Gunjan Pandey Balal Paikauli 979214477 7 Gonda Nawabganj Nawabganj gird 271303 Nawabganj gird Mahmood ahmad 983850691 8 Shravasti Shravasti Jamunaha 271803 MaharooMurtiha Nafees Ahmad MaharooMurtiha 991941625 9 Badaun Budaun2 Kisrua 243601 Village KISRUA Shailendra Singh 5835005612 10 Badaun Gunnor Babrala 243751 Babrala Ajit Singh Yadav Babrala 5836237097 11 Bareilly Bareilly2 Bareilly Npp(U) 243201 TALPURA BAHERI JASVEER GIR Talpura 7037003700 12 Bareilly Bareilly3 Kyara(R) 243001 Kareilly BRIJESH KUMAR Kareilly 7037081113 13 Bareilly Bareilly5 Bareilly Nn 243003 CHIPI TOLA MAHFUZ AHMAD Chipi tola 7037260356 14 Bareilly Bareilly1 Bareilly Nn(U) 243006 DURGA NAGAR VINAY KUMAR GUPTA Nawada jogiyan 7037769541 15 Badaun Budaun1 shahavajpur 243638 shahavajpur Jay Kishan shahavajpur 7037970292 16 Faizabad Faizabad5 Askaranpur 224204 Askaranpur Kanchan ASKARANPUR 7052115061 17 Faizabad Faizabad2 Mosodha(R) 224201 Madhavpur Deepchand Gupta Madhavpur -

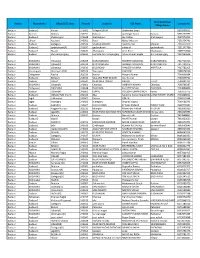

Bareilly Zone CSC List

S Grampanchayat N District Block Name Village/CSC name Pincode Location VLE Name Contact No Village Name o Badaun Budaun2 Kisrua 243601 Village KISRUA Shailendra Singh 5835005612 Badaun Gunnor Babrala 243751 Babrala Ajit Singh Yadav Babrala 5836237097 Badaun Budaun1 shahavajpur 243638 shahavajpur Jay Kishan shahavajpur 7037970292 Badaun Ujhani Nausera 243601 Rural Mukul Maurya 7351054741 Badaun Budaun Dataganj 243631 VILLEGE MARORI Ajeet Kumar Marauri 7351070370 Badaun Budaun2 qadarchowk(R) 243637 qadarchowk sifate ali qadarchowk 7351147786 Badaun Budaun1 Bisauli 243632 dhanupura Amir Khan Dhanupura 7409212060 Badaun Budaun shri narayanganj 243639 mohalla shri narayanganj Ashok Kumar Gupta shri narayanganj 7417290516 Badaun BUDAUN1 Ujhani(U) 243639 NARAYANGANJ SHOBHIT AGRAWAL NARAYANGANJ 7417721016 Badaun BUDAUN1 Ujhani(U) 243639 NARAYANGANJ SHOBHIT AGRAWAL NARAYANGANJ 7417721016 Badaun BUDAUN1 Ujhani(U) 243639 BILSI ROAD PRADEEP MISHRA AHIRTOLA 7417782205 Badaun Vazeerganj Wazirganj (NP) 202526 Wazirganj YASH PAL 7499478130 Badaun Dahgawan Nadha 202523 Nadha Mayank Kumar 7500006864 Badaun Budaun2 Bichpuri 243631 VILL AND POST MIAUN Atul Kumar 7500379752 Badaun Budaun Ushait 243641 NEAR IDEA TOWER DHRUV Ushait 7500401211 Badaun BUDAUN1 Ujhani(R) 243601 Chandau AMBRISH KUMAR Chandau 7500766387 Badaun Dahgawan DANDARA 243638 DANDARA KULDEEP SINGH DANDARA 7534890000 Badaun Budaun Ujhani(R) 243601 KURAU YOGESH KUMAR SINGH Kurau 7535079775 Badaun Budaun2 Udhaiti Patti Sharki 202524 Bilsi Sandeep Kumar ShankhdharUGHAITI PATTI SHARKI 7535868001 -

Find Address of Your Nearest Loan Center and Phone Number of Concerned Focal Person

Find address of your nearest loan center and phone number of concerned focal person Loan Center/ S.No. Province District PO Name City / Tehsil Focal Person Contact No. Union Council/ Location Address Branch Name Akhuwat Islamic College Chowk Oppsite Boys College 1 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Bagh Bagh Bagh Nadeem Ahmed 0314-5273451 Microfinance (AIM) Sudan Galli Road Baagh Akhuwat Islamic Muzaffarabad Road Near main bazar 2 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Bagh Dhir Kot Dhir Kot Nadeem Ahmed 0314-5273451 Microfinance (AIM) dhir kot Akhuwat Islamic Mang bajri arja near chambar hotel 3 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Bagh Harighel Harighel Nadeem Ahmed 0314-5273451 Microfinance (AIM) Harighel Akhuwat Islamic 4 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Bhimber Bhimber Bhimber Arshad Mehmood 0346-4663605 Kotli Mor Near Muslim & School Microfinance (AIM) Akhuwat Islamic 5 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Bhimber Barnala Barnala Arshad Mehmood 0346-4663605 Main Road Bimber & Barnala Road Microfinance (AIM) Akhuwat Islamic Main choki Bazar near Sir Syed girls 6 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Bhimber Samahni Samahni Arshad Mehmood 0346-4663605 Microfinance (AIM) College choki Samahni Helping Hand for Adnan Anwar HHRD Distrcict Office Relief and Hattian,Near Smart Electronics,Choke 7 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Hattian Hattian UC Hattian Adnan Anwer 0341-9488995 Development Bazar, PO, Tehsil and District (HHRD) Hattianbala. Helping Hand for Adnan Anwar HHRD Distrcict Office Relief and Hattian,Near Smart Electronics,Choke 8 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Hattian Hattian UC Langla Adnan Anwer 0341-9488995 Development Bazar, PO, Tehsil and District (HHRD) Hattianbala. Helping Hand for Relief and Zahid Hussain HHRD Lamnian office 9 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Hattian Hattian UC Lamnian Zahid Hussain 0345-9071063 Development Main Lamnian Bazar Hattian Bala. -

Hindu Masjids

purnn / / >f L / ' I Y*1 r *** J ' M l | HlNDU MASJIDS By the same author: • The Saffron Book (available) Many Splendoured Hindutva • An Unflnished Agenda Population transfer • Anti-Hindus Cover: Depiets the deseeration of mandirs and their conversion into masjids b Hindu Mashds Prafull Goradia Tareett CONTEMPORARY TARGETT PRAFULL PVT LTD Former publisher of Capital, India’s only business weekly from 1888 to 1935 C IV Hindu Masjids © 2002, PRAPULL GORADIA First Reprint 2004 ISBN 81-7523-311-8 Published by Contemporary Targett Prafull Pvt. Ltd., 203-A Prakash House, 4379/4B, Ansari Road, New Delhi - 1 10 002. Printed and bound in India at Replika Press Pvt. Ltd. Friendship between the Hindus and the Muslims is essential if India is to eateh up on its lost eenturies Contents Dedieation List of Photographs I The Challenge 1 The Conflict II Shuddhi in Stone 2 Shuddhi by British Temple beheaded for the ego of Aurangzeb 3 ineomplete Shuddhi Ramjanm abhoomi 4 Spontaneous Shuddhi The spontaneous use ofthe dargah of Sultan Ghari where Hindus pertorm puja side by side with Muslims pertorming ibaadat 5 Waterloo pf Aryavarta Kannauj was the eentre otnorthern Hindustan until it was destroyed by Muslim invaders 6 Reelaimed Temple at Mahaban Temple ofRohini, deseerated by Mahmud Ghazni, Alauddin and Aurangzeb, again a mandir 7 Outbuddin and 27 Mandirs Deseeration near Qutb Minar viii Hindu Mcisjids 8 Instant Vandalism 54 ln 60 hours a set ofsplendid temples at Ajmerwere converted into a masjid 9 Ghazni to Alamgir 63 Repeated destruetion at Mathura 10 -

List of Famous Mosque in the World

SNo Name Country City Year Group Remarks Abdul Rahman 1 Afghanistan Kabul 2009 U The largest mosque of Afghanistan. Mosque Also known as the Friday Mosque of Shrine of the 18th 2 Afghanistan Kandahar U Kandahar, it houses the cloak worn by the Cloak century Prophet Muhammad. The mosque was the city's first congregational Friday Mosque mosque, built on the site of two smaller 3 Afghanistan Herat 1446 C of Herat Zorastrian Fire temples destroyed by earthquake and fire. Shrine of Mazari also known as Blue Mosque or Rawze-e- 4 Afghanistan ?U Hazrat Ali Sharif Sharif Located in the centre of Albania's capital, the Et'hem Bey 5 Albania Tirana 1823 T mosque was closed during communist rule Mosque until 1991. Great Mosque 6 Algeria Algiers 1097 U of Algiers Ketchaoua 7 Algeria Algiers 1612 U Mosque King Fahd Largest mosque in Latin America. Named 8 Islamic Argentina Buenos Aires 2006 SA after Fahd of Saudi Arabia. Cultural Center 9 Blue Mosque Armenia Yerevan 1766 SH Auburn Auburn 10 Gallipoli Australia 1979 T Turkish Sunni Muslims (Sydney) Mosque Lebanese Moslems Association. Also known Lakemba Lakemba 11 Australia 1977 U as the Imam Ali Bin Abi Taleb Mosque after Mosque (Sydney) Ali 12 Telfs Mosque Austria Telfs 1998 U Minaret later built in 2006 Vienna Islamic 13 Austria Vienna 1977 U Built in order of rey Faisal ibn Abd al-Aziz. Centre Rasheed Built by Muslims of Ghana, Nigeria and 14 Austria Vienna 2005 U Mosque Benin. Mosque Bad Built by Muslims of Turkey, has two small 15 Austria Bad Vöslau 2009 U Vöslau minarets Al Fateh Named for Ahmed ibn Muhammad ibn 16 Bahrain Juffair 2006 U Mosque Khalifa Baitul National mosque. -

Pictorial Compendium of Projects/Works Completed During 2019-20 (Ut Sector)

PICTORIAL PICTORIAL 2A COMPENDIUM PICTORIAL COMPENDIUM OF PROJECTS/WORKS COMPLETED DURING 2019-20 (UT SECTOR) FINANCE DEPARTMENT 2A GOVERNMENT OF JAMMU & KASHMIR PICTORIAL COMPENDIUM 2A of Projects/Works Completed during 2019-20 (UT sector) FINANCE DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF JAMMU & KASHMIR Designed by Web Chasers, Srinagar Published by Finance Department, Govt. of J&K Publication Year: August 2020 DR ARUN KUMAR MEHTA FINANCE COMMISSIONER IAS FINANCE, J&K he benefits of development percolate down to the masses primarily only after projects/works get complet- ed in a time bound manner with adherence to all requisite norms and maintenance of quality parameters. TThe UT of J&K is committed to change the perception and tradition where by projects were executed and tenders invited without budgetary support besides frequently changing the specifications and project designs resulting in cost and time overruns. Finance Department has laid sharp focus on completion of development projects, their physical verification and concurrent evaluation so that remedial measures are taken even during the course of execution of the projects/ works. These measures clubbed with making Administrative Approvals, Technical Sanctions, implementation of Pulse application, making photographic evidence before and after execution of projects mandatory etc. will ulti- mately lead to efficiency in planning, management and monitoring of the developmental activities. A picture is worth a thousand words. Proper documentation of development projects completed with photo- graphic evidences is an effort towards our endeavour for brining transparency and accountability in execution of works. The pictorial compendium of projects/works completed during 2019-20 (UT sector) has been prepared by the Expenditure Division-II of the Finance Department. -

Investigating the Effects of Persian Architecture Principals on Traditional

4832 Hanie Okhovat et al./ Elixir His. Pre. 39 (2011) 4832-4835 Available online at www.elixirpublishers.com (Elixir International Journal) Historic Preservation Elixir His. Pre. 39 (2011) 4832-4835 Investigating the effects of Persian architecture principals on traditional buildings and landscapes in Kashmir Hanie Okhovat 1 and Mohammad Reza Pourjafar 2 1Department of Architecture, University of Tarbiat Modares, Jalal Ale Ahmad St, Tehran, Iran. 2Department of Architecture, Faculty of Art, University of Tarbiat Modares, Jalal Ale Ahmad St, Tehran, Iran. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: North of the Punjab the land rises into the Himalayan foothills, towards the snows. Received: 15 July 2011; Politically, the hills are divided between the states of Jammu and Kashmir. To the north, Received in revised form: beyond the Banihal Pass, lies the Kashmir Valley, over 5000 feet above sea- level. The Vale 22 September 2011; and its fringes are rich in timber, which was and remains the primary building material. Tall Accepted: 28 September 2011; houses lining the Jhelum River in Srinagar are wood-framed, as are more handsome mosques, which take a form unique to Kashmir. Persian influence on Indian Culture is a vast Keywords subject with many sides to it. This research is based on just one aspect of it, that is, the role Kashmir, of Persian architecture on Indian landscape architecture, and in particular Kashmir cultural Persian Culture, architecture. Islamic Architecture, © 2011 Elixir All rights reserved. Influence. Introduction Srinagar(Fig. 1,2), the Pattar Masjid (1623) and the Akhun The Persian architecture in Kashmir flourished under the Mulla Shah's mosque (1649). -

Sufism in the West

Sufism in the West With the increasing Muslim diaspora in post-modern Western societies, Sufism – intellectually as well as sociologically – may eventually become mainstream Islam itself due to its versatile potential, especially in the wake of what has been called the failure of political Islam world-wide. Sufism in the West provides a timely account of this subject and is primarily concerned with the latest developments in the history of Sufism and elaborates the ideas and institutions which organise Sufism and folk- religious practices. The topics discussed include: • The orders and movements • Their social base • Organisation and institutionalisation • Recruitment-patterns in new environments • Channels of disseminating ideas, such as ritual, charisma, and organisation • Reasons for their popularity among certain social groups • The nature of their affiliation with the countries of their origin Sufism in the West is essential reading for students and academics with research interests in Islam, Islamic History and Social Anthropology. John Hinnells is former Professor and founding chair of the Department for the Study of Religion at the School of Oriental and African Studies, London University. His main research interest is in Zoroastrianism and has also edited the New Penguin Dictionary of Religions and the New Penguin Handbook of Living Religions. Jamal Malik is Chair of Religious Studies and Islamic Studies at the University of Erfurt, Germany. His areas of interest and research are Islamic Religion, Social History of Muslim South