Indigenous Knowledge Dissemination-Still Not There

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harmful Industrial Activities Other Natural World Heritage Sites

MAP HARMFUL INDUSTRIAL 169 79 170 191 ACTIVITIES 171 100 87 151 45 43 168 WWF DEFINES HARMFUL 44 INDUSTRIAL ACTIVITIES AS: 207 172 204 80 Operations that cause major 167 38 39 81 94 23 203 disturbances or changes to the 46 93 166 141 42 40 94 94 122 218 193192 99 character of marine or terrestrial 165 41 115 114 164 environments. Such activities are of 221 179 119 71 35 173 91 88 142 34 concern due to their potential to involve 220 197 96 62 118 186 95 194 large impacts on the attributes of 217 112 199 222 184 200 214 215 198 113 56 outstanding universal value and other 52 162 101 51 163 natural, economic and cultural values. 136 212 105 58 54 120 187 85 121 53 61 The impacts of these activities are 185 144 50 55 117 140 103 145 60 57 219 137 213 1 104102 often long-term or permanent. 49 59 They can also be of concern due 72 22 139 106 224 138 73 134 48 216 135 149 226 to their impacts on the sustainability 24 116 97 82 175 196 225 of local livelihoods, and/or because 98 133 195 174 176 86 they put at risk the health, safety or 150 227 65 67 160 154 68 47 107 well-being of communities. Harmful 153 63 70 188 161 152 132 159 66 64 223 69 189 industrial activities are often, but not 190 36 74 37 124 131 exclusively, conducted by multinational 76 92 78 125 83 84 77 201202 123 enterprises and their subsidiaries. -

Harmful Industrial Activities Other Natural World Heritage Sites

MAP HARMFUL INDUSTRIAL 169 79 170 191 ACTIVITIES 171 100 87 151 45 43 168 WWF DEFINES HARMFUL 44 INDUSTRIAL ACTIVITIES AS: 207 172 204 80 Operations that cause major 167 38 39 81 94 23 203 disturbances or changes to the 46 93 166 141 42 40 94 94 122 218 193192 99 character of marine or terrestrial 165 41 115 114 164 environments. Such activities are of 221 179 119 230 71 35 173 91 88 142 34 concern due to their potential to involve 220 231 197 96 62 118 186 95 194 large impacts on the attributes of 217 112 199 222 184 200 214 215 198 113 56 outstanding universal value and other 52 162 101 51 163 natural, economic and cultural values. 136 212 105 58 54 120 187 85 121 53 61 The impacts of these activities are 185 144 50 55 117 140 103 145 60 57 219 137 213 1 104102 often long-term or permanent. 49 59 They can also be of concern due 72 22 139 106 224 138 73 134 48 216 135 149 226 to their impacts on the sustainability 24 116 97 82 175 196 225 of local livelihoods, and/or because 98 133 195 174 176 86 they put at risk the health, safety or 150 227 65 67 160 154 68 47 107 well-being of communities. Harmful 153 63 70 188 161 152 132 159 66 64 223 69 189 industrial activities are often, but not 190 36 74 37 124 131 exclusively, conducted by multinational 76 92 78 125 83 84 77 201202 123 enterprises and their subsidiaries. -

IUCN World Heritage Outlook 2014

IUCN World Heritage Outlook 2014 A conservation assessment of all natural World Heritage sites About IUCN environment and development challenges. IUCN’s work focuses on valuing and conserving nature, ensuring effective and equitable governance of its use, and IUCN World Heritage Outlook 2014 together to develop policy, laws and best practice. IUCN is the world’s oldest and largest global environmental organization, with more than 1,200 government and A conservation assessment of all natural NGO Members and almost 11,000 volunteer experts in some 160 countries. IUCN’s work is supported by over World Heritage sites www.iucn.org About the IUCN World Heritage Programme IUCN is the advisory body on nature to the UNESCO World Heritage Committee. Working closely with IUCN Members, Commissions and Partners, and especially the World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA), and with a range of partners, IUCN’s World Heritage Programme evaluates new sites nominated to the World Heritage List, monitors the conservation of listed sites, promotes the World Heritage Convention as a leading global instrument for conservation, and provides support, advice and training to site managers, governments, scientists and local communities. The IUCN World Heritage Programme also initiates innovative ways to enhance the role of the World Heritage Convention in protecting the planet’s biodiversity and natural heritage and positioning the worlds’ most iconic places as exemplars of nature-based solutions to global challenges. www.iucn.org/worldheritage IUCN WORLD HERITAGE oUTLOOK 2014 Disclaimers Contents The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN or other participating organizations concerning the 4 Foreword legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

World Heritage in Philippine Ancestral Domains: Negotiating

PHILIPPINES RIGHTS AND WORLD HERITAGE BRIEF June 2016 World Heritage in Philippine Ancestral Domains: Negotiating Rights through Indigenous Heritage Three of the six World Heritage sites in the Philippines are situated within territories of indigenous peoples (IPs) who have lived in these lands for many generations. The Ifugao Rice Terraces (IRT), a ‘living cultural landscape,’ were carved out by the Ifugao. Apart from being haven for rich biodiversity that include endangered species, the natural heritage sites Puerto Princesa Underground River (PPUR) and Mt. Hamiguitan Range, are home to Tagbanwas, and to Mandaya and Manobo communities respectively. The outstanding universal values (OUVs) of the IRT, PPUR and Mt. Hamiguitan Range Wildlife Sanctuary owe largely to the lifeways of the IP groups that have through thousands of years sustainably managed these properties. Although IPs’ contributions in maintaining the sites are acknowledged and their rights are enshrined in the Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act (IPRA) of 1997, poverty and other rights issues could only reflect difficulties in implementing rights-based approaches, including those that are borne by overlapping and/or conflicting provisions in heritage and environmental policies. The need to resolve contradictions and nuances between the IPRA and national environmental laws and WH policies is paramount for people to reclaim their heritage and realize their right to socio-economic and cultural well-being. In-depth researches and databases in these diverse natural and cultural settings are prerequisites for negotiations as well as for crafting site-specific and national policies and programs. A multi-disciplinary, participatory approach at all stages is indispensable given the very complex issues and sociocultural contexts. -

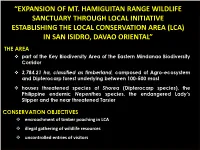

Expansion of Mt. Hamiguitan Range Wildlife

“EXPANSION OF MT. HAMIGUITAN RANGE WILDLIFE SANCTUARY THROUGH LOCAL INITIATIVE ESTABLISHING THE LOCAL CONSERVATION AREA (LCA) IN SAN ISIDRO, DAVAO ORIENTAL” THE AREA part of the Key Biodiversity Area of the Eastern Mindanao Biodiversity Corridor 3,784.21 ha, classified as timberland, composed of Agro-ecosystem and Dipterocarp forest underlying between 100-500 masl houses threatened species of Shorea (Dipterocarp species), the Philippine endemic Nepenthes species, the endangered Lady’s Slipper and the near threatened Tarsier CONSERVATION OBJECTIVES encroachment of timber poaching in LCA illegal gathering of wildlife resources uncontrolled entries of visitors MHRWS HISTORY: A Significant Milestone •1965 – marks the beginning for the discovery of a splendid, fascinating and beautiful Mount Hamiguitan Range Wildlife Sanctuary in San Isidro, Davao Oriental, Philippines. •In same year – an old Mandaya Chieftain Daramba Bago persistently requested the then young writer Justina MB. Yu to write a story about what they considered the “mysterious Mount Hamiguitan”, whose peak was always covered with clouds. However, Ms. Yu did not act on the request because of the inaccessibility of the area. •28 years later in 1993 – Ms. Yu became the Mayor of San Isidro and that she sent a group to document the Hidden Lake near the peak. The documenters also accidentally discovered the outstanding landscape of stunted old dwarf trees at the tip of Mount Hamiguitan. •1994 – because of patient and constant request of Mayor Yu, House of Representative Member Honorable Thelma Almario filed House Bill No. 3872 entitled “An Act Declaring Mount Hamiguitan in the Municipality of San Isidro, Province of Davao Oriental, a National Park, Providing for its Development and Appropriating Funds Thereof”. -

Adventures of TUAN

The Adventures of TUAN A Comic Book on Responsible Tourism in ASEAN Heritage Parks 1 The Adventures of TUAN A Comic Book on Responsible Tourism in ASEAN Heritage Parks The Adventures of Tuan: A Comic Book on Responsible Tourism in ASEAN Heritage Parks Being a nature-lover and a travel enthusiast, Tuan’s ultimate dream is to visit all ASEAN Heritage Parks (AHPs). AHPs are protected areas of high conservation importance, preserving in total a complete spectrum of representative ecosystems of the ASEAN region. The ASEAN Heritage Parks (AHP) Programme is one of the flagship biodiversity conservation programmes of ASEAN. The establishment of AHPs stresses that the ASEAN Member States (AMS) share a common natural heritage and should collaborate in their efforts to protect the rich biodiversity that supports the lives of millions of people in the region. The ASEAN Centre for Biodiversity (ACB) serves as the Secretariat of the AHP Programme. This comic book will take us to Tuan’s adventures in each AHP that he visited and will teach us important lessons on how to become responsible tourists in protected areas. The AHPs featured in this publication are Tasek Merimbun Heritage Park of Brunei Darussalam; Virachey National Park of Cambodia; Kepulauan Seribu Marine National Park of Indonesia; Nam Ha National Protected Area of Lao PDR; Gunung Mulu National Park of Malaysia; Indawgyi Lake Wildlife Sanctuary of Myanmar; Mount Makiling Forest Reserve of the Philippines; Bukit Timah Nature Reserve of Singapore; Ao Phang Nga-Mu Ko Surin-Mu Ko Similan National Park of Thailand; and Hoang Lien National Park of Viet Nam. -

Chemical and Physical Properties of Soils in Mt. Apo and Mt. Hamiguitan, Mindanao, the Philippines

Asian Soil Research Journal 1(2): 1-11, 2018; Article no.ASRJ.42460 Chemical and Physical Properties of Soils in Mt. Apo and Mt. Hamiguitan, Mindanao, the Philippines Nonilona P. Daquiado1*, Raul M. Ebuña1, Renato G. Tabañag1, Perfecto B. Bojo2 and Victor B. Amoroso3 1Department of Soil Science, College of Agriculture, CMU, Philippines. 2Department of Agricultural Engineering, College of Engineering, CMU, Philippines. 3Center for Biodiversity Research and Extension in Mindanao (CEBREM), CMU, Philippines. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration between all authors. Authors RME, RGT and PBB were involved in the survey, delineation and establishment of the one-hectare permanent plot in each site, collection of soil samples and soil profile description. Author NPD prepared the protocol, performed the analyses of soil samples, interpreted the results, wrote the draft of the manuscript. Author VBA did some corrections and proof reading of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/ASRJ/2018/v1i2675 Editor(s): (1) Dr. Tunira Bhadauria, Professor, Department of Zoology, Kanpur University, U .P, India. Reviewers: (1) Fábio Henrique Portella Corrêa de Oliveira, Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco, Brazil. (2) Şana Sungur, Mustafa Kemal University, Turkey. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/25355 Received 5th April 2018 Accepted 14th June 2018 Original Research Article Published 2nd July 2018 ABSTRACT Aims: The study was aimed to determine the edaphic qualities of two Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) sites in Mindanao; Mt Apo in Cotabato and Mt. Hamiguitan in Davao Oriental, the Philippines Study Design: Random soil sampling within the plots Place and Duration of Study: Analyses of the soil samples collected from each site were performed at Soil and Plant Analysis Laboratory (SPAL), Central Mindanao University, Musuan, Bukidnon, the Philippines from October, 2012 to December 2013. -

Peter W. Fritsch Victor B. Amoroso Fulgent P. Coritico Darin S. Penneys

VACCINIUM HAMIGUITANENSE (ERICACEAE), A NEW SPECIES FROM THE PHILIPPINES Peter W. Fritsch Victor B. Amoroso Botanical Research Institute of Texas Center for Biodiversity Research and 1700 University Dr. Extension in Mindanao (CEBREM) and Fort Worth, Texas 76107, U.S.A. Department of Biology, College of Arts and Sciences [email protected] Central Mindanao University Musuan, Bukidnon 8710 PHILIPPINES [email protected] Fulgent P. Coritico Darin S. Penneys Center for Biodiversity Research and Department of Biology and Marine Biology Extension in Mindanao (CEBREM) and University of North Carolina Wilmington Department of Biology, College of Arts and Sciences 601 S. College Road Central Mindanao University Wilmington, North Carolina 28403, U.S.A. Musuan, Bukidnon 8710 PHILIPPINES [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Vaccinium hamiguitanense, a new species from the Philippines, is described and illustrated. The new species is most similar to V. gitin‑ gense Hook. f. but differs by having smaller leaf blades, leaf blade margins with 2 to 4 impressed more or less evenly distributed crenations (glands) per side, inflorescences with fewer flowers, shorter pedicels that are puberulent and muriculate, and a glabrous floral disk. The new species is endemic to Mt. Hamiguitan Range Wildlife Sanctuary in Davao Oriental Province of Mindanao Island in Tropical Upper Montane Rain Forest and low (“bonsai”) forest on clay derived from ultramafic rock. We assign an IUCN Red List preliminary status as Data Deficient. ABSTRAK Inilalarawan sa ulat na ito ang isang bagong species ng halaman mula sa Pilipinas, ang Vaccinium hamiguitanense. Kahawig ng bagong species ang V. gitingense Hook f., ngunit mas maliit ang mga dahon, bawat isa ay may 2 hanggang 4 na kapansin-pansin at halos pantay- pantay na mga umbok sa parehong gilid (mga glandula), mas kakaunti ang bulaklak kada kumpol, bawat isa ay mas maikli ang tangkay na pinalilibutan ng maliliit ngunit magagaspang na buhok, at ang floral disk ay makinis. -

Inventory and Conservation of Endangered, Endemic and Economically Important Flora of Hamiguitan Range, Southern Philippines

Blumea 54, 2009: 71–76 www.ingentaconnect.com/content/nhn/blumea RESEARCH ARTICLE doi:10.3767/000651909X474113 Inventory and conservation of endangered, endemic and economically important flora of Hamiguitan Range, southern Philippines V.B. Amoroso 1, L.D. Obsioma1, J.B. Arlalejo2, R.A. Aspiras1, D.P. Capili1, J.J.A. Polizon1, E.B. Sumile2 Key words Abstract This research was conducted to inventory and assess the flora of Mt Hamiguitan. Field reconnaissance and transect walk showed four vegetation types, namely: dipterocarp, montane, typical mossy and mossy-pygmy assessment forests. Inventory of plants showed a total of 878 species, 342 genera and 136 families. Of these, 698 were an- diversity giosperms, 25 gymnosperms, 41 ferns and 14 fern allies. Assessment of conservation status revealed 163 endemic, Philippines protected area 34 threatened, 33 rare and 204 economically important species. Noteworthy findings include 8 species as new vegetation types record in Mindanao and one species as new record in the Philippines. Density of threatened species is highest in the dipterocarp forest and decreases at higher elevation. Species richness was highest in the montane forest and lowest in typical mossy forest. Endemism increases from the dipterocarp to the montane forest but is lower in the mossy forest. The results are compared with data from other areas. Published on 30 October 2009 INTRODUCTION METHODOLOGY Mount Hamiguitan Range Wildlife Sanctuary in Davao Ori- Vegetation types ental is a protected area covering 6 834 ha located between Field reconnaissance and transect walks were conducted 6°46'6°40'01" to 6°46'60" N and 126°09'02" to 126°13'01" E. -

Inventory of Orchids in the Mount Hamiguitan Range Wildlife Sanctuary, Davao Oriental, Philippines Stela A

Bio Bulletin 4(1): 37-42(2018) (Published by Research Trend, Website: www.biobulletin.com) ISSN NO. (Print): 2454-7913 ISSN NO. (Online): 2454-7921 Inventory of orchids in the Mount Hamiguitan Range Wildlife Sanctuary, Davao Oriental, Philippines Stela A. Dizon1, Ana P. Ocenar1 and Mark Arcebal K. Naive2* 1Department of Natural Sciences, College of Arts and Sciences, University of Southeastern Philippines, 263 Iñigo St, Obrero, Davao City, Philippines. 2Department of Biological Sciences, College of Science and Mathematics, Mindanao State University-Iligan Institute of Technology, Andres Bonifacio Ave, Iligan City, 9200 Lanao del Norte, Philippines. (Corresponding author: Mark Arcebal K. Naive) (Published by Research Trend, Website: www.biobulletin.com) (Received 09 March 2018; Accepted 22 April 2018) ABSTRACT: The orchid family is the most threatened group of plants in the Philippines, and remains to be poorly known and studied. A thorough survey was done from the base to the peak of the mountain Mount Hamiguitan Range Wildlife Sanctuary (MHRWS) to record and identify the orchid species. MHRWS harbors 45 species of orchids, 23 of them are Philippine endemic, a few may be undescribed. About 53% are epiphytes and 47% are terrestrial. The remarkable richness of orchids found in the present study highlights the importance for conservation of flora in MHRWS and other mountains and forests reserves in Mindanao. Keywords: Davao Oriental, Orchidaceae, Mindanao, Mount Hamiguitan, Philippines How to cite this article: Dizon, S.A., Ocenar, A.P. and Naïve, M.A.K. (2018). Inventory of orchids in the Mount Hamiguitan Range Wildlife Sanctuary, Davao Oriental, Philippines. Bio Bulletin, 4(1): 37-42. -

Nematode Diversity of Phytotelmata of Nepenthes Spp. in Mount Hamiguitan Range Wildlife Sanctuary, Philippines

Ghent University Faculty of Sciences Department of Biology Academic Year 2011-2013 Nematode diversity of phytotelmata of Nepenthes spp. in Mount Hamiguitan Range Wildlife Sanctuary, Philippines JOESEPH SELLADO QUISADO Promoter: Prof. Dr. WIM BERT & Thesis submitted to obtain the degree of Dr. IRMA TANDINGAN DE LEY Master of Science in Nematology Nematode diversity of phytotelmata of Nepenthes spp. in Mount Hamiguitan Range Wildlife Sanctuary, Philippines JOESEPH SELLADO QUISADO Nematology Section, Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, Ghent University; K.L. Ledeganckstraat 35, 9000 Ghent, Belgium [email protected]/[email protected] Summary – Nematodes from phytotelmata of Nepenthes hamiguitanensis and N. peltata in Mt. Hamiguitan, Philippines included three new species of the genera: Molgolaimus Ditlevsen 1921, Dominicactinolaimus Jairajpuri and Ahmad 1992, Tripylella (Bütschli, 1873) Brzeski & Winiszewska-Ślipińska, 1993; two known: Tylocephalus auriculatus (Bütschli, 1873) Anderson, 1966, Pelodera strongyloides (Schneider, 1860) Schneider 1866; and three uncertain species of the genera: Paractinolaimus Meyl 1957, Plectus Bastian 1865, and Anaplectus De Coninck & Schuurmans Stekhoven 1933. Measurements and illustrations are provided. Molgolaimus sp. nov. is characterized by the absence of pre-cloacal supplements, shape of the spicule with lamina widened distally, conical tail with swollen tip and without digitate prolongation, and sexual dimorphism in the shape of the cardia (elongated in male and more round in females). Moreover, a comprehensive key for the genus Molgolaimus is presented. Dominicactinolaimus sp. nov. is characterized by short body length, long tail (c = 6.6-7.6) and 6-7 pre-cloacal supplements. The generic position of Dominicatinolaimus is reaffirmed and the synonymy with Trachypleurosum or Trachactinolaimus is rejected. -

Philippine Master Plan for Climate Resilient Forestry Development

PHILIPPINE MASTER PLAN FOR CLIMATE RESILIENT FORESTRY DEVELOPMENT January 2016 Contents Page Table of Contents i List of Figures iv List of Tables v List of Acronyms/Abbreviations vi Definition of Terms xi Executive Summary xiv 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Rationale for Updating and Climate Proofing the 2003 RMPFD 1 1.2 Methodology 2 2. Status of Implementation of the 2003 Revised Master Plan for Forestry Development (RMPFD) 7 3. The Forestry Scenarios 14 3.1 Climate Trends and Climate Change Scenarios 16 3.1.1 Climate Trends in the Philippines 16 3.1.2 Future Climate Scenario and Associated Hazards 18 Increased Temperature 18 More Intense Rainfall Events 20 Typhoons 23 Sea Level Rise (SLR) and Storm Surges 24 3.1.3 Climate Change Impacts 25 Impacts on Ecosystems 26 Impacts on Water Supply 26 Impacts on Communities 28 Impacts on Livelihoods 28 3.2 Demand and Supply of Forest Ecosystems-related Goods and Services 29 3.2.1 Demand and Supply of Wood and Fuelwood 30 Round Wood Equivalent (RWE) Demand and Supply of Wood 30 Demand and Supply of Fuelwood and Charcoal 36 3.2.2 Demand and Supply of Forest Ecosystems Services 38 Demand for Water 40 Demand for other Forest Ecosystems-related Services 48 3.3 Governance Scenario 54 Philippine Master Plan for Climate Resilient Forestry Development i 3.3.1 Current Governance of the Forestry Sector 54 3.3.2 Projected Scenario in the Governance of the Forestry Sector 62 3.3.3 Governance Scenario for the Updated and Climate Resilient RMPFD 65 4.