Magnetism in the Eighteenth Century H.H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloading Material Is Agreeing to Abide by the Terms of the Repository Licence

Cronfa - Swansea University Open Access Repository _____________________________________________________________ This is an author produced version of a paper published in: Transactions of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion Cronfa URL for this paper: http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa40899 _____________________________________________________________ Paper: Tucker, J. Richard Price and the History of Science. Transactions of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, 23, 69- 86. _____________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence. Copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ 69 RICHARD PRICE AND THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE John V. Tucker Abstract Richard Price (1723–1791) was born in south Wales and practised as a minister of religion in London. He was also a keen scientist who wrote extensively about mathematics, astronomy, and electricity, and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. Written in support of a national history of science for Wales, this article explores the legacy of Richard Price and his considerable contribution to science and the intellectual history of Wales. -

Cavendish the Experimental Life

Cavendish The Experimental Life Revised Second Edition Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge Series Editors Ian T. Baldwin, Gerd Graßhoff, Jürgen Renn, Dagmar Schäfer, Robert Schlögl, Bernard F. Schutz Edition Open Access Development Team Lindy Divarci, Georg Pflanz, Klaus Thoden, Dirk Wintergrün. The Edition Open Access (EOA) platform was founded to bring together publi- cation initiatives seeking to disseminate the results of scholarly work in a format that combines traditional publications with the digital medium. It currently hosts the open-access publications of the “Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge” (MPRL) and “Edition Open Sources” (EOS). EOA is open to host other open access initiatives similar in conception and spirit, in accordance with the Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the sciences and humanities, which was launched by the Max Planck Society in 2003. By combining the advantages of traditional publications and the digital medium, the platform offers a new way of publishing research and of studying historical topics or current issues in relation to primary materials that are otherwise not easily available. The volumes are available both as printed books and as online open access publications. They are directed at scholars and students of various disciplines, and at a broader public interested in how science shapes our world. Cavendish The Experimental Life Revised Second Edition Christa Jungnickel and Russell McCormmach Studies 7 Studies 7 Communicated by Jed Z. Buchwald Editorial Team: Lindy Divarci, Georg Pflanz, Bendix Düker, Caroline Frank, Beatrice Hermann, Beatrice Hilke Image Processing: Digitization Group of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Cover Image: Chemical Laboratory. -

Very Rough Draft

Friends and Colleagues: Intellectual Networking in England 1760-1776 Master‟s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of Comparative History Mark Hulliung, Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Master‟s Degree by Jennifer M. Warburton May 2010 Copyright by Jennifer Warburton May 2010 ABSTRACT Friends and Colleagues: Intellectual Networking in England 1760- 1776 A Thesis Presented to the Comparative History Department Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Waltham, Massachusetts By Jennifer Warburton The study of English intellectualism during the latter half of the Eighteenth Century has been fairly limited. Either historians study individual figures, individual groups or single debates, primarily that following the French Revolution. My paper seeks to find the origins of this French Revolution debate through examining the interactions between individuals and the groups they belonged to in order to transcend the segmentation previous scholarship has imposed. At the center of this study are a series of individuals, most notably Joseph Priestley, Richard Price, Benjamin Franklin, Dr. John Canton, Rev. Theophilus Lindsey and John Jebb, whose friendships and interactions among such diverse disciplines as religion, science and politics characterized the collaborative yet segmented nature of English society, which contrasted so dramatically with the salon culture of their French counterparts. iii Table of Contents INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................ -

Chapter 1 Neither Indeed Would I Have Put My Selfe to the Labour Of

Notes Neither indeed would I have put my selfe to the labour of writing any Notes at all, if the booke could as well have wanted them, as I could easilie have found as well, or better to my minde, how to bestow my time. Marcus Aurelius Antoninus. Chapter 1 1. This description is from Hacking's introduction to the English trans lation of Maistrov [1974, p.vii]. 2. Forsaking, in this respect, what is described in the 14th edition [1939] of the Encyclopaedia Britannica as its "career of plain usefulness" [vol. 3, p.596]. A supplementary volume of the Dictionary, soon to be published, will contain a note on Thomas Bayes. 3. See Barnard [1958, p.293]. 4. The note, by Thomas Fisher, LL.D., reads in its entirety as follows: "Bayes, Thomas, a presbyterian minister, for some time assistant to his father, Joshua Bayes, but afterwards settled as pastor of a con gregation at Tunbridge Wells, where he died, April 17, 1761. He was F.R.S., and distinguished as a mathematician. He took part in the controversy on fluxions against Bishop Berkeley, by publishing an anonymous pamphlet, entitled "An Introduction to the Doctrine of Fluxions, and Defence of the Mathematicians against the Author of the Analyst," London, 1736, 8vo. He is the author of two math ematical papers in the Philosophical Transactions. An anonymous tract by him, under the title of "Divine Benevolence" , in reply to one on Divine Rectitude, by John Balguy, likewise anonymous, attracted much attention." For further comments on this reference see Ander son [1941, p.161]. -

JOHN MICHELL's THEORY of MATTER and JOSEPH PRIESTLEY's USE of IT John Schondelmayer Parry Doe4e..T of Philosophy Department of H

JOHN MICHELL'S THEORY OF MATTER AND JOSEPH PRIESTLEY'S USE OF IT John Schondelmayer Parry muster Doe4e..T of Philosophy Department of History of Science and Technology, Imperial College of Science and Technology, University of London 2 ABSTRACT John Michell (1724-1793) developed a theory of penetrable matter in which a bi -polar (attractive and repulsive) power consti- tuted substance, and made itself sensible through the properties of matter. His sensationalist epistemology was similar to Locke's, though he denied the essential passivity and impenetrability of matter which both Locke and Newton had espoused in favour of a monist synthesis of matter and power. Michell supposed that immediate contact and the mutual penetration of matter were not absolutely prevented but only inhibited by repulsive powers at the surfaces of bodies, and he explained light's emission, momentum and resulting ability to penetrate transparent substances by the interaction of the powers of light particles with the surface powers of luminous bodies and receiving bodies. Joseph Priestley (1733-1804) adopted many of Michell's ideas on matter and light, and described them in his History of Optics, (1 772) . Nckli fritmdsh,i0, frurn, 17In8, Wed. Wte die v's i r*rest. '1■-■ ihcb o f mg-Tier, et.d helpcd k.11-, See *its pzie4ic, t He accepted Michell's ideas on penetrability, immediate contact, and the basic role of powers, a5 well Qs -4e tp;st-th)Divlb 1.z1A4.0k. tive5-e ides; and ; (A-Oz I 464.5 prtroiclect 114A t41.41, 4 he hears whereby kiz GoLa ci areept "to red*Fh-e -

James Bowdoin: Patriot and Man of the Enlightenment

N COLLEGE M 1 ne Bowdoin College Library [Digitized by tlie Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/jamesbowdoinpatrOObowd 52. James BowdoinU^ Version B, ca. i 791, by Christian GuUager Frontisfiece JAMES BOWDOIN Patriot and Man of the Enlightenment By Professor Gordon E. Kershaw EDITED BY MARTHA DEAN CATALOGUE By R. Peter Mooz EDITED BY LYNN C. YANOK An exhibition held at the BOWDOIN COLLEGE MUSEUM OF ART Brunswick, Maine May 28 through September 12, 1976 © Copyright 1976 by The President and Trustees of Bowdoin College, Brunswick, Maine Front cover illustration: Number 16, James Bozvdoin II, by Robert Feke, 1748, Bowdoin College Museum of Art. Back cover illustrations: Number 48, Silhouette of James Bowdoin II, by an Unknown Artist, courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society; Number 47, signature of James Bowdoin II, from Autografh Letter, Boston, 1788, per- mission of Dr. and Mrs. R. Peter Mooz. This exhibition and catalogue were organized with the aid of grants from the Maine State American Revolution Bicentennial Commission and The First National Bank of Boston. Tyfesetting by The AntJioensen Press, Portland, Maine Printed by Salina Press, Inc., East Syracuse, Nezv York Contents List of Illustrations iv Foreword and Acknowledgments, r. peter mooz vii Chronology xi JAMES BOWDOIN: Patriot and Man of The Enlightenment, gordon e. kershaw i Notes 90 Catalogue, r. peter mooz 97 Bibliography 108 Plates III List of Illustrations Except as noted, the illustrations appear following the text and are numbered in the order as shown in the exhibition. o. 1. Sames Bozvdoi/i /, ca. 1725, by an Unknown Artist 2. -

Br^Heastregion O0T 1969

br heastregion UNITED STATES ^ DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR O0T 1969 NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Independence National Historical Park 313 Walnut Street He Affairs IN REPLY REFER TO: Philadelphia, Pa. 19106 Asst. HP, Admin. October 10, 1969 Pri-^onncl property i, Finance Aj^s^RD, Opération F MAlntananee Memorandum To: Regional Director, Northeast Region From: Special Assistant to the Director Subject: Franklin Court Enclosed are copies of the following reports representing the latest studies of Franklin Court: 1. John Platt, Franklin's House, September 5 , 1969. 2. Penelope H. Batbheler, An Architectural Summary of Franklin Court and Benjamin Franklin's House, September 18, 1969. 3 . John Cotter, "Summary Reports on Archeology of Franklin Court" April 10, 1969, with copy of Bruce Povell's, The Archeology of Franklin Court, November 9 > 19^2. 4. Charles G. Dorman, The Furnishings of Franklin Court 1765-1790, ^July, 1969* Ronald F. Lee Enclosures (4) / 1' f INiD£,-¡(4 !oC2*~ zw ! \zn<te£ s 1. TWO HOMECOMINGS IN THE LIFE OF BENJAMIN FRANKLIN The Provincial of I?62 Returns "I got home v/ell the first of November, and had the happiness to find my little family perfectly well, My house has been full of a succession Cof my friends! ...from morning to night ever since my arrival, congratulating me on my return with the utmost cordiality and affection..* *, and they would...they say, if I had not disappointed them by coming privately to town, have met me'with five hundred horse." Benjamin Franklin, Esquire, late Agent of the iu ^ o 1 Province of Pennsylvania at the Court of His Most Serene Majesty, Deputy Postmaster-General of North America, and Fellow of the P-oyal Society, recently admitted by Oxford University to the degree of doctor of civil laws honoris causa, had already eclipsed the achievements of any and every Ameri- * can up to that time. -

Richard Price and the History of Science

69 RICHARD PRICE AND THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE John V. Tucker Abstract Richard Price (1723–1791) was born in south Wales and practised as a minister of religion in London. He was also a keen scientist who wrote extensively about mathematics, astronomy, and electricity, and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. Written in support of a national history of science for Wales, this article explores the legacy of Richard Price and his considerable contribution to science and the intellectual history of Wales. The article argues that Price’s real contribution to science was in the field of probability theory and actuarial calculations. Introduction Richard Price was born in Llangeinor, near Bridgend, in 1723. His life was that of a Dissenting Minister in Newington Green, London. He died in 1791. He is well remembered for his writings on politics and the affairs of his day – such as the American and French Revolutions. Liberal, republican, and deeply engaged with ideas and intellectuals, he is a major thinker of the eighteenth century. He is certainly pre-eminent in Welsh intellectual history. Richard Price was also deeply engaged with science. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society for good reasons. He wrote about mathematics, astronomy and electricity. He had scientific equipment at home. He was consulted on scientific questions. He was a central figure in an eighteenth-century network of scientific people. He developed the mathematics and data needed to place pensions and insurance on a sound foundation – a contribution to applied mathematics that has led to huge computational, financial and social progress. -

Bayes Biography

The Reverend Thomas Bayes FRS: a Biography to Celebrate the Tercentenary of his Birth by D.R. Bellhouse Department of Statistical and Actuarial Sciences University of Western Ontario London, Ontario Canada N6A 5B7 Abstract Thomas Bayes, from whom Bayes Theorem takes its name, was probably born in 1701 so that the year 2001 would mark the 300th anniversary of his birth. A sketch of his life will include his family background and education, as well as his scientific and theological work. In contrast to some, but not all, biographies of Bayes, the current biography is an attempt to cover areas be- yond Bayes’s scientific work. When commenting on the writing of scientific biography, Pearson (1978) stated, “it is impossible to understand a man’s work unless you understand something of his character and unless you understand something of his environment. And his environment means the state of affairs social and political of his own age.” The intention here is to follow this general approach to biography. There is very little primary source material on Bayes and his work. For example, only three of his letters and a notebook containing some sketches of his own work, almost all unpub- lished, as well as notes on the work of others were known to have survived. Neither the letters, nor the notebook, are dated, and only one of the letters can be dated accurately from internal evi- dence. This biography will contain new information about Bayes. In particular, among the papers of the 2nd Earl Stanhope, letters and papers of Bayes have been uncovered that were previously not known to exist. -

The Study of Magnetism and Terrestrial Magnetism in Great Britain, C 1750-1830 Robinson Mclaughry Yost Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1997 Lodestone and earth: the study of magnetism and terrestrial magnetism in Great Britain, c 1750-1830 Robinson McLaughry Yost Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the European History Commons, and the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Yost, Robinson McLaughry, "Lodestone and earth: the study of magnetism and terrestrial magnetism in Great Britain, c 1750-1830 " (1997). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 11758. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/11758 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Physics in the Enlightenment

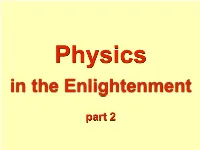

Physics in the Enlightenment part 2 Electricity and magnetism from Gilbert to Volta Important dates in the history of electricity 1600 Gilbert versorium, electrics, non-electrics 1629 Cabeo electric repulsion 1660 Guericke electrostatic machine (sulphur sphere), electric repulsion and transmission 1705 Hauksbee electrostatic machine (glass sphere), 1729 Gray motion of electricity (to about 300 m) 1733 Dufay two kinds of electricity: glass and resin 1739 Desaguliers conductors and isolators Important dates in the history of electricity 1745 Kleist Musschenbroek Leyden jar Cunaeus 1746 Watson one electric fluid 1747 Franklin one electric fluid 1759 Symmer two electric fluids 1752 Franklin lightning rod 1775 Volta electrophore 2 1785 Coulomb F ~ Q1Q2/r (1746 Kratzenstein, 1760 D. Bernoulli, 1766 Priestley, 1769 Robison, 1772 Cavendish) 1791 Galvani animal electricity 1800 Volta contact potential, electric pile William Gilbert - De magnete (1600) The first systematic study of electrification by means of versorium (a rotating needle) ”electrics”: amber, jet, diamond, sapphire, opal, amethyst, beryl, carbuncle, iris stone (quartz), rock crystal, sulphur, fluorspar, belemnites, orpiment, glass, hard resin, sal gemma, sealing wax, antimony glass, rock alum, mica... ”non-electrics”: all metals, alabaster, agate, the marbles, pearls, ebony, coral, porphyre, emerald, chalcedony, jasper, bloodstone, corundum, flint, bone, the hardest woods (cedar, cypress, juniper)... Early graphic representations of the magnetic field Cabeo (1629) Rohault (1671) Lana (1692) Vallemont (1696) Dalencé (1687) Electrostatic machines Glass sphere Hauksbee (1705) Sulphur sphere Guericke (1660) Various types of electrostatic machines The Leyden jar (1745) Ewald von Kleist (Kammin, then Prussia) (now Kamień Pomorski, Poland) Pieter van Musschenbroek Andreas Cunaeus (Leyden) "I am going to tell you about a new but terrible experiment which I advise you not to try yourself, nor would I, who have experienced it and survived by the grace of God, do it again for all the kingdom of France. -

1 on Some Recently Discovered Manuscripts of Thomas Bayes By

On Some Recently Discovered Manuscripts of Thomas Bayes by D.R. Bellhouse Department of Statistical and Actuarial Sciences University of Western Ontario London, Ontario Canada N6A 5B7 Abstract A set of manuscripts attributed to Thomas Bayes was recently discovered among the Stanhope of Chevening papers housed in the Centre for Kentish studies. One group of the manuscripts is directly related to Bayes posthumous paper on infinite series. These manuscripts also show that the paper on infinite series was directly motivated by results in Maclaurin’s A Treatise of Fluxions. Four other manuscripts in the collection cover a variety of mathematical topics spanning the solution to polynomial equations to infinite series expansions of powers of the arcsine function. It is conjectured that one of latter manuscripts, on the subject of trinomial divisors, predates Bayes’s election to the Royal Society in 1742. From the style of writing of the manuscripts, it is speculated that Richard Price, who presented Bayes’s now famous essay on inverse probability to the Royal Society, had more of a hand in the printed version of the essay than just the transmission of its contents. MSC 1991 subject classifications: 01A50, 40A30. 1 1. Introduction Thomas Bayes (1701? – 1761) is now famous for his posthumous essay (Bayes 1763a) that gave first expression to what is now known as Bayes Theorem. Bayes’s paper was communicated to the Royal Society after his death by his friend Richard Price. Excellent treatments of Bayes’s original theorem are given in Stigler (1986) and Dale (1999). His original theorem and approach to probabilistic prediction remained unused and relatively forgotten until Laplace independently rediscovered it and promoted its use later in the 18th century.