NGO Report to UN Human Rights Committee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learning from Japan? Interpretations of Honda Motors by Strategic Management Theorists

Are cross-shareholdings of Japanese corporations dissolving? Evolution and implications MITSUAKI OKABE NISSAN OCCASIONAL PAPER SERIES NO. 33 2001 NISSAN OCCASIONAL PAPER SERIES FULL LIST OF PAST PAPERS No.1 Yamanouchi Hisaaki, Oe Kenzaburô and Contemporary Japanese Literature. No.2 Ishida Takeshi, The Introduction of Western Political concepts into Japan. No.3 Sandra Wilson, Pro-Western Intellectuals and the Manchurian Crisis. No.4 Asahi Jôji, A New Conception of Technology Education in Japan. No.5 R John Pritchard, An Overview of the Historical Importance of the Tokyo War Trial. No.6 Sir Sydney Giffard, Change in Japan. No.7 Ishida Hiroshi, Class Structure and Status Hierarchies in Contemporary Japan. No.8 Ishida Hiroshi, Robert Erikson and John H Goldthorpe, Intergenerational Class Mobility in Post-War Japan. No.9 Peter Dale, The Myth of Japanese Uniqueness Revisited. No.10 Abe Shirô, Political Consciousness of Trade Union Members in Japan. No.11 Roger Goodman, Who’s Looking at Whom? Japanese, South Korean and English Educational Reform in Comparative Perspective. No.12 Hugh Richardson, EC-Japan Relations - After Adolescence. No.13 Sir Hugh Cortazzi, British Influence in Japan Since the End of the Occupation (1952-1984). No.14 David Williams, Reporting the Death of the Emperor Showa. No.15 Susan Napier, The Logic of Inversion: Twentieth Century Japanese Utopias. No.16 Alice Lam, Women and Equal Employment Opportunities in Japan. No.17 Ian Reader, Sendatsu and the Development of Contemporary Japanese Pilgrimage. No.18 Watanabe Osamu, Nakasone Yasuhiro and Post-War Conservative Politics: An Historical Interpretation. No.19 Hirota Teruyuki, Marriage, Education and Social Mobility in a Former Samurai Society after the Meiji Restoration. -

Caught Between Hope and Despair: an Analysis of the Japanese Criminal Justice System

Denver Journal of International Law & Policy Volume 31 Number 4 Fall Article 2 April 2020 Caught between Hope and Despair: An Analysis of the Japanese Criminal Justice System Melissa Clack Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/djilp Recommended Citation Melissa Clack, Caught between Hope and Despair: An Analysis of the Japanese Criminal Justice System, 31 Denv. J. Int'l L. & Pol'y 525 (2003). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Journal of International Law & Policy by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. CAUGHT BETWEEN HOPE AND DESPAIR: AN ANALYSIS OF THE JAPANESE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM Melissa Clack* INTRODUCTION While handcuffed, shackled, forced to excrete in their own clothes, personally bathed by the warden, sleep deprived, food deprived, bribed with cigarettes or food, and, in some cases, "accidentally" killed, a suspect in Japan is interrogated and the world is beginning to acknowledge that such procedures amount to a violation of human rights.' Adopted December 10, 1948, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was the first international statement to use the term "human rights" and to recognize the right to be free from torture, arbitrary arrest, as well as the right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty. 2 Although the International community has concluded that suspects 3 should be commonly afforded particular rights, there are many disparities from country to country as to what rights are actually guaranteed.4 Overall, industrialized nations afford more rights than do developing countries, with one exception.5 Japan, unlike most * Bachelor of Criminal Justice and B.A. -

Legal Protection for Migrant Trainees in Japan: Using International Standards to Evaluate Shifts in Japanese Immigration Policy

10_BHATTACHARJEE (DO NOT DELETE) 10/14/2014 8:20 PM LEGAL PROTECTION FOR MIGRANT TRAINEES IN JAPAN: USING INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS TO EVALUATE SHIFTS IN JAPANESE IMMIGRATION POLICY SHIKHA SILLIMAN BHATTACHARJEE* Japan’s steady decline in population since 2005, combined with the low national birth rate, has led to industrial labor shortages, particularly in farming, fishing, and small manufacturing industries. 1 Japan’s dual labor market structure leaves smaller firms and subcontractors with labor shortages in times of both economic growth and recession. 2 As a result, small-scale manufacturers and employers in these industries are increasingly reliant upon foreign workers, particularly from China, Vietnam, Indonesia, and the Philippines.3 Temporary migration programs, designed to allow migrant workers to reside and work in a host country without creating a permanent entitlement to residence, have the potential to address the economic needs of both sending and receiving countries.4 In fact, the United Nations Global Commission on International Migration recommends: “states and the private sector should consider the option of introducing carefully designed temporary migration programmes as a means of addressing the economic needs of both countries of origin and destination.”5 “Most high- * Shikha Silliman Bhattacharjee is a Fellow in the Asia Division at Human Rights Watch. 1 Apichai Shipper, Contesting Foreigner’s Rights in Contemporary Japan, N.C. J. INT’L L. & COM. REG., 505-06 (2011). 2 Ritu Vij, Review, 64 J. ASIAN STUD. 469-71 (May 2005) (reviewing HIROSHI KOMAI, FOREIGN MIGRANTS IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN (2001)). 3 Shipper, supra note 1, at 506. 4 This definition does not exclude the possibility that migrants admitted to host countries may be granted permanent residence. -

The Legalization of Hinomaru and Kimigayo As Japan's National Flag

The legalization of Hinomaru and Kimigayo as Japan's national flag and anthem and its connections to the political campaign of "healthy nationalism and internationalism" Marit Bruaset Institutt for østeuropeiske og orientalske studier, Universitetet i Oslo Vår 2003 Introduction The main focus of this thesis is the legalization of Hinomaru and Kimigayo as the national flag and anthem of Japan in 1999 and its connections to what seems to be an atypical Japanese form of postwar nationalism. In the 1980s a campaign headed by among others Prime Minister Nakasone was promoted to increase the pride of the Japanese in their nation and to achieve a “transformation of national consciousness”.1 Its supporters tended to use the term “healthy nationalism and internationalism”. When discussing the legalization of Hinomaru and Kimigayo as the national flag and anthem of Japan, it is necessary to look into the nationalism that became evident in the 1980s and see to what extent the legalization is connected with it. Furthermore we must discuss whether the legalization would have been possible without the emergence of so- called “healthy nationalism and internationalism”. Thus it is first necessary to discuss and try to clarify the confusing terms of “healthy nationalism and patriotism”. Secondly, we must look into why and how the so-called “healthy nationalism and internationalism” occurred and address the question of why its occurrence was controversial. The field of education seems to be the area of Japanese society where the controversy regarding its occurrence was strongest. The Ministry of Education, Monbushō, and the Japan Teachers' Union, Nihon Kyōshokuin Kumiai (hereafter Nikkyōso), were the main opponents struggling over the issue of Hinomaru, and especially Kimigayo, due to its lyrics praising the emperor. -

Civil Society and the State in Democratic East Asia

PROTEST AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS Chiavacci, (eds) Grano & Obinger Civil Society and the State in Democratic East Asia East Democratic in State the and Society Civil Edited by David Chiavacci, Simona Grano, and Julia Obinger Civil Society and the State in Democratic East Asia Between Entanglement and Contention in Post High Growth Civil Society and the State in Democratic East Asia Protest and Social Movements Recent years have seen an explosion of protest movements around the world, and academic theories are racing to catch up with them. This series aims to further our understanding of the origins, dealings, decisions, and outcomes of social movements by fostering dialogue among many traditions of thought, across European nations and across continents. All theoretical perspectives are welcome. Books in the series typically combine theory with empirical research, dealing with various types of mobilization, from neighborhood groups to revolutions. We especially welcome work that synthesizes or compares different approaches to social movements, such as cultural and structural traditions, micro- and macro-social, economic and ideal, or qualitative and quantitative. Books in the series will be published in English. One goal is to encourage non- native speakers to introduce their work to Anglophone audiences. Another is to maximize accessibility: all books will be available in open access within a year after printed publication. Series Editors Jan Willem Duyvendak is professor of Sociology at the University of Amsterdam. James M. Jasper teaches at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. Civil Society and the State in Democratic East Asia Between Entanglement and Contention in Post High Growth Edited by David Chiavacci, Simona Grano, and Julia Obinger Amsterdam University Press Published with the support of the Swiss National Science Foundation. -

Lesbians in Japan and South Korea

Her Story: Lesbians in Japan and South Korea Elise Fylling EAST 4590 – Master’s Thesis in East Asian Studies African and Asian Studies 60 credits – spring 2012 Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages Faculty of Humanities University of Oslo Her Story: Lesbians in Japan and South Korea Master’s thesis, Elise Fylling © Elise Fylling 2012 Her Story: Lesbians in Japan and South Korea Elise Fylling Academic supervisor: Vladimir Tikhonov http://www.duo.uio.no Printed by: Webergs Printshop Summary Lesbians in Japan and South Korea have long been ignored in both academic, and in social context. The assumption that there are no lesbians in Japan or South Korea dominates a large population in these societies, because lesbians do not identify as such in the public domain. Instead they often live double lives showing one side of themselves to the public and another in private. Although there exist no formal laws against homosexuality, a social barrier in relation to coming out to one’s family, friends or co-workers is highly present. Shame, embarrassment and fear of being rejected as deviant or abnormal makes it difficult to step outside of the bonds put on by society’s hetero-normative structures. What is it like to be lesbian in contemporary Japan and South Korea? In my dissertation I look closely at the Japanese and South Korean society’s attitudes towards young lesbians, examining their experiences concerning identity, invisibility, family relations, the question of marriage and how they see themselves in society. I also touch upon how they meet others in spite of their invisibility as well as giving some insight to the way they chose to live their life. -

The Burakumin Myth of Everyday Life: Reformulating Identity In

From Subnational to Micronational: Buraku Communities and Transformations in Identity in Modern and Contemporary Japan Rositsa Mutafchieva East Asian Studies McGill University, Montreal April 2009 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the PhD degree © Rositsa Mutafchieva 2009 1 Table of Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................... 3 Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................... 5 Introduction: Burakumin: A Minority in Flux ............................................................ 8 Chapter One: Moments in the History of Constructing Outcast Spaces ......... 19 Chapter Two: Three Buraku Communitiees, Three Different Stories ............... 52 Chapter Three: Instructions Given: ―Building a Nation = Building a Community‖ .............................................................................................................. 112 Chapter Four: The Voices of the Buraku ............................................................. 133 Chapter Five: ―Community Building‖ Revisited................................................... 157 Conclusion ................................................................................................................ 180 Appendix ................................................................................................................... 192 Bibliography............................................................................................................. -

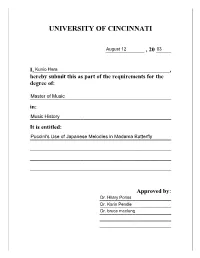

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI _____________ , 20 _____ I,______________________________________________, hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: ________________________________________________ in: ________________________________________________ It is entitled: ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ Approved by: ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ PUCCINI’S USE OF JAPANESE MELODIES IN MADAMA BUTTERFLY A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2003 by Kunio Hara B.M., University of Cincinnati, 2000 Committee Chair: Dr. Hilary Poriss ABSTRACT One of the more striking aspects of exoticism in Puccini’s Madama Butterfly is the extent to which the composer incorporated Japanese musical material in his score. From the earliest discussion of the work, musicologists have identified many Japanese melodies and musical characteristics that Puccini used in this work. Some have argued that this approach indicates Puccini’s preoccupation with creating an authentic Japanese setting within his opera; others have maintained that Puccini wanted to produce an exotic atmosphere -

The Japanese Workers' Committee for Human Rights (JWCHR) and the Organization to Support the Lawsuits for Freedom of Education in Tokyo

THE JAPANESE WORKERS’ COMMITTEE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS - JWCHR NGO in Special Consultative Status with ECOSOC c/o Tokyo Regional Council of Trade Unions – TOKYO CHIHYO 2-33-10 Minami-Otsuka, Toshima-ku, Tokyo 170-0005 Japan Tel: +81-3-3943-2420 Fax: +81-3-3943-2431 e-mail: [email protected] Joint Report Improve the Low Level of Human Rights in Japan to the International Level! JWCHR report April, 2012 for the 2nd UPR of Japan Jointly prepared by the Japanese Workers' Committee for Human Rights (JWCHR) and the Organization to Support the Lawsuits for Freedom of Education in Tokyo JWCHR submitted a report for the first review of Japan by UPR, where two of our members participated in the working session to watch the progress. On that occasion, UPR secretariat kindly distributed all the reports submitted by 23 Japanese NGOs, to which we would like to express our deep respect for their hard work. We are also grateful to those member states of the Human Rights Counc il who, despite their close political and economical relation with the Government of Japan, reviewed the NGO reports and offered appropriated recommendations. However, it is regrettable that the Government of Japan does not make meaningful efforts to improve the situation nor to heed the recommendations. JWHCR submit our report to the second UPR of Japan including some additional information. The Government has not taken measures to correct the situation over a long period of time on the matters recommended by various Governments in connection with relevant human rights conventions and treaties. -

Constitutional Revolution in Japanese Law, Society and Politics*

OccAsioNAl PApERs/ REpRiNTS SERiEs iN CoNTEMpoRARY • '• AsiAN STudiEs ' NUMBER 5 - 1982 (50) a•' CONSTITUTIONAL REVOLUTION IN JAPANESE LAW, SOCIETY AND I • POLITICS •• Lawrence W. Beer School of LAw UNivERsiTy of 0 •• MARylANd. c::;. ' Q Occasional Papers/Reprint Series in Contemporary Asian Studies General Editor: Hungdah Chiu Executive Editor: David Salem Managing Editor: Shirley Lay Editorial Advisory Board Professor Robert A. Scalapino, University of California at Berkeley Professor Martin Wilbur, Columbia University Professor Gaston J. Sigur, George Washington University Professor Shao-chuan Leng, University of Virginia Professor Lawrence W. Beer, University of Colorado Professor James Hsiung, New York University Dr. Robert Heuser, Max-Planck-Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law at Heidelberg Dr. Lih-wu Han, Political Science Association of the Republic of China Professor K. P. Misra, Jawaharlal Nehru University, India Professor J. S. Prybyla, The Pennsylvania State University Professor Toshio Sawada, Sophia University, Japan Published with the cooperation of the Maryland International Law Society All contributions (in English only) and communications should be sent to Professor Hungdah Chiu, University of Maryland School of Law, 500 West Baltimore Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201 USA. All publications in this series reflect only the views of the authors. While the editor accepts responsibility for the selection of materials to be published, the individual author is responsible for statements of facts and expressions of opinion contained therein. Subscription is US $10.00 for 8 issues (regardless of the price of individual issues) in the United States and Canada and $12.00 for overseas. Check should be addressed to OPRSCAS and sent to Professor Hungdah Chiu. -

An Analysis of Nationalist Influence on Japanese Human Rights Policy

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College International Studies Honors Projects International Studies Department 4-2019 One Nation, One Race: An Analysis of Nationalist Influence on Japanese Human Rights Policy Garrett J. Schoonover Macalester College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/intlstudies_honors Part of the International and Area Studies Commons, and the Japanese Studies Commons Recommended Citation Schoonover, Garrett J., "One Nation, One Race: An Analysis of Nationalist Influence on Japanese Human Rights Policy" (2019). International Studies Honors Projects. 34. https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/intlstudies_honors/34 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the International Studies Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Studies Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. One Nation, One Race: An Analysis of Nationalist Influence on Japanese Human Rights Policy Garrett Schoonover An Honors Thesis Submitted to the International Studies Department at Macalester College, Saint Paul, Minnesota, USA Faculty Advisor: Nadya Nedelsky April 19, 2019 Schoonover 1 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 4 Introduction 5 Chapter 1: Literature Review 14 The Nation and Nationalism 15 Japanese National Identity 21 Conclusion 28 Chapter 2: History of Japanese Nationalism -

Public Diplomacy and LGBT Rights

#LGBTinPD EDITORIAL POLICY Public Diplomacy Magazine seeks contributions for each themed issue based on a structured solicitation system. Submissions must be invited by the editorial board. Unsolicited articles will not be considered or returned. Authors interested in contributing to Public Diplomacy Magazine should contact the editorial board about their proposals. Articles submitted to Public Diplomacy Magazine are reviewed by the editorial board, which is composed entirely of graduate students enrolled in the Master of Public Diplomacy program at the University of Southern California. Articles are evaluated based on relevance, originality, prose, and argumentation. The editor- in-chief, in consultation with the editorial board, holds final authority for accepting or refusing submissions for publication. Authors are responsible for ensuring the accuracy of their statements. The editorial staff will not conduct fact checks, but edit submissions for basic formatting and stylistic consistency only. Editors reserve the right to make changes in accordance with Public Diplomacy Magazine style specifications. Copyright of published articles remains with Public Diplomacy Magazine. No article in its entirety or parts thereof may be published in any form without proper citation credit. ABOUT PUBLIC DIPLOMACY MAGAZINE Public Diplomacy Magazine is a publication of the Association of Public Diplomacy Scholars (APDS) at the University of Southern California, with support from the USC Center on Public Diplomacy at the Annenberg School, USC Dana and David Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences School of International Relations, and the Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. Its unique mission is to provide a common forum for the views of both scholars and practitioners from around the globe, in order to explore key concepts in the study and practice of public diplomacy.