Caught Between Hope and Despair: an Analysis of the Japanese Criminal Justice System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learning from Japan? Interpretations of Honda Motors by Strategic Management Theorists

Are cross-shareholdings of Japanese corporations dissolving? Evolution and implications MITSUAKI OKABE NISSAN OCCASIONAL PAPER SERIES NO. 33 2001 NISSAN OCCASIONAL PAPER SERIES FULL LIST OF PAST PAPERS No.1 Yamanouchi Hisaaki, Oe Kenzaburô and Contemporary Japanese Literature. No.2 Ishida Takeshi, The Introduction of Western Political concepts into Japan. No.3 Sandra Wilson, Pro-Western Intellectuals and the Manchurian Crisis. No.4 Asahi Jôji, A New Conception of Technology Education in Japan. No.5 R John Pritchard, An Overview of the Historical Importance of the Tokyo War Trial. No.6 Sir Sydney Giffard, Change in Japan. No.7 Ishida Hiroshi, Class Structure and Status Hierarchies in Contemporary Japan. No.8 Ishida Hiroshi, Robert Erikson and John H Goldthorpe, Intergenerational Class Mobility in Post-War Japan. No.9 Peter Dale, The Myth of Japanese Uniqueness Revisited. No.10 Abe Shirô, Political Consciousness of Trade Union Members in Japan. No.11 Roger Goodman, Who’s Looking at Whom? Japanese, South Korean and English Educational Reform in Comparative Perspective. No.12 Hugh Richardson, EC-Japan Relations - After Adolescence. No.13 Sir Hugh Cortazzi, British Influence in Japan Since the End of the Occupation (1952-1984). No.14 David Williams, Reporting the Death of the Emperor Showa. No.15 Susan Napier, The Logic of Inversion: Twentieth Century Japanese Utopias. No.16 Alice Lam, Women and Equal Employment Opportunities in Japan. No.17 Ian Reader, Sendatsu and the Development of Contemporary Japanese Pilgrimage. No.18 Watanabe Osamu, Nakasone Yasuhiro and Post-War Conservative Politics: An Historical Interpretation. No.19 Hirota Teruyuki, Marriage, Education and Social Mobility in a Former Samurai Society after the Meiji Restoration. -

The Rise of Nationalism in Millennial Japan

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2010 Politics Shifts Right: The Rise of Nationalism in Millennial Japan Jordan Dickson College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Dickson, Jordan, "Politics Shifts Right: The Rise of Nationalism in Millennial Japan" (2010). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 752. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/752 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Politics Shifts Right: The Rise of Nationalism in Millennial Japan A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelors of Arts in Global Studies from The College of William and Mary by Jordan Dickson Accepted for High Honors Professor Rachel DiNitto, Director Professor Hiroshi Kitamura Professor Eric Han 1 Introduction In the 1990s, Japan experienced a series of devastating internal political, economic and social problems that changed the landscape irrevocably. A sense of national panic and crisis was ignited in 1995 when Japan experienced the Great Hanshin earthquake and the Aum Shinrikyō attack, the notorious sarin gas attack in the Tokyo subway. These disasters came on the heels of economic collapse, and the nation seemed to be falling into a downward spiral. The Japanese lamented the decline of traditional values, social hegemony, political awareness and engagement. -

The Culture of Capital Punishment in Japan David T

MIGRATION,PALGRAVE ADVANCES IN CRIMINOLOGY DIASPORASAND CRIMINAL AND JUSTICE CITIZENSHIP IN ASIA The Culture of Capital Punishment in Japan David T. Johnson Palgrave Advances in Criminology and Criminal Justice in Asia Series Editors Bill Hebenton Criminology & Criminal Justice University of Manchester Manchester, UK Susyan Jou School of Criminology National Taipei University Taipei, Taiwan Lennon Y.C. Chang School of Social Sciences Monash University Melbourne, Australia This bold and innovative series provides a much needed intellectual space for global scholars to showcase criminological scholarship in and on Asia. Refecting upon the broad variety of methodological traditions in Asia, the series aims to create a greater multi-directional, cross-national under- standing between Eastern and Western scholars and enhance the feld of comparative criminology. The series welcomes contributions across all aspects of criminology and criminal justice as well as interdisciplinary studies in sociology, law, crime science and psychology, which cover the wider Asia region including China, Hong Kong, India, Japan, Korea, Macao, Malaysia, Pakistan, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14719 David T. Johnson The Culture of Capital Punishment in Japan David T. Johnson University of Hawaii at Mānoa Honolulu, HI, USA Palgrave Advances in Criminology and Criminal Justice in Asia ISBN 978-3-030-32085-0 ISBN 978-3-030-32086-7 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32086-7 This title was frst published in Japanese by Iwanami Shinsho, 2019 as “アメリカ人のみた日本 の死刑”. [Amerikajin no Mita Nihon no Shikei] © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020. -

21St-Century Yakuza: Recent Trends in Organized Crime in Japan ~Part 1 21世紀のやくざ ―― 日本における組織犯罪の最近動 向

Volume 10 | Issue 7 | Number 2 | Article ID 3688 | Feb 11, 2012 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus 21st-Century Yakuza: Recent Trends in Organized Crime in Japan ~Part 1 21世紀のやくざ ―― 日本における組織犯罪の最近動 向 Andrew Rankin government called on yakuza bosses to lend tens of thousands of their men as security 21st-Century Yakuza: Recent Trends guards.6 Corruption scandals entwined in Organized Crime in Japan ~ Part parliamentary lawmakers and yakuza 1 21 世紀のやくざ ―― 日本における lawbreakers throughout the 1970s and 1980s. 組織犯罪の最近動向 One history of Japan would be a history of gangs: official gangs and unofficial gangs. The Andrew Rankin relationships between the two sides are complex and fluid, with boundaries continually I - The Structure and Activities of the being reassessed, redrawn, or erased. Yakuza The important role played by the yakuza in Japan has had a love-hate relationship with its Japan’s postwar economic rise is well 7 outlaws. Medieval seafaring bands freelanced documented. But in the late 1980s, when it as mercenaries for the warlords or provided became clear that the gangs had progressed far security for trading vessels; when not needed beyond their traditional rackets into real estate they were hunted as pirates.1 Horse-thieves development, stock market speculation and and mounted raiders sold their skills to military full-fledged corporate management, the tide households in return for a degree of tolerance turned against them. For the past two decades toward their banditry.2 In the 1600s urban the yakuza have faced stricter anti-organized street gangs policed their own neighborhoods crime laws, more aggressive law enforcement, while fighting with samurai in the service of the and rising intolerance toward their presence Shogun. -

Japan's Quasi-Jury and Grand Jury Systems As Deliberative Agents of Social Change: De-Colonial Strategies and Deliberative Participatory Democracy

Chicago-Kent Law Review Volume 86 Issue 2 Symposium on Comparative Jury Article 12 Systems April 2011 Japan's Quasi-Jury and Grand Jury Systems as Deliberative Agents of Social Change: De-Colonial Strategies and Deliberative Participatory Democracy Hiroshi Fukurai Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Criminal Procedure Commons Recommended Citation Hiroshi Fukurai, Japan's Quasi-Jury and Grand Jury Systems as Deliberative Agents of Social Change: De- Colonial Strategies and Deliberative Participatory Democracy, 86 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 789 (2011). Available at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview/vol86/iss2/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago-Kent Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. JAPAN'S QUASI-JURY AND GRAND JURY SYSTEMS AS DELIBERATIVE AGENTS OF SOCIAL CHANGE: DE-COLONIAL STRATEGIES AND DELIBERATIVE PARTICIPATORY DEMOCRACY HIROSHI FUKuRAI* INTRODUCTION May 21, 2009 signaled the beginning of Japan's paradigmatic shift in its effort to democratize its judicial institutions. The Japanese government finally introduced two significant judicial institutions, i.e., the Quasi-Jury (Saiban-in) and the new Grand Jury (Kensatsu Shinsakai or Prosecutorial Review Commission (PRC)) systems. 1 Establishing these twin judicial bodies of lay adjudication helped broaden the institution of decision- making in criminal matters to include a representative panel of Japanese citizens chosen at random from local communities. -

Legal Protection for Migrant Trainees in Japan: Using International Standards to Evaluate Shifts in Japanese Immigration Policy

10_BHATTACHARJEE (DO NOT DELETE) 10/14/2014 8:20 PM LEGAL PROTECTION FOR MIGRANT TRAINEES IN JAPAN: USING INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS TO EVALUATE SHIFTS IN JAPANESE IMMIGRATION POLICY SHIKHA SILLIMAN BHATTACHARJEE* Japan’s steady decline in population since 2005, combined with the low national birth rate, has led to industrial labor shortages, particularly in farming, fishing, and small manufacturing industries. 1 Japan’s dual labor market structure leaves smaller firms and subcontractors with labor shortages in times of both economic growth and recession. 2 As a result, small-scale manufacturers and employers in these industries are increasingly reliant upon foreign workers, particularly from China, Vietnam, Indonesia, and the Philippines.3 Temporary migration programs, designed to allow migrant workers to reside and work in a host country without creating a permanent entitlement to residence, have the potential to address the economic needs of both sending and receiving countries.4 In fact, the United Nations Global Commission on International Migration recommends: “states and the private sector should consider the option of introducing carefully designed temporary migration programmes as a means of addressing the economic needs of both countries of origin and destination.”5 “Most high- * Shikha Silliman Bhattacharjee is a Fellow in the Asia Division at Human Rights Watch. 1 Apichai Shipper, Contesting Foreigner’s Rights in Contemporary Japan, N.C. J. INT’L L. & COM. REG., 505-06 (2011). 2 Ritu Vij, Review, 64 J. ASIAN STUD. 469-71 (May 2005) (reviewing HIROSHI KOMAI, FOREIGN MIGRANTS IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN (2001)). 3 Shipper, supra note 1, at 506. 4 This definition does not exclude the possibility that migrants admitted to host countries may be granted permanent residence. -

Is Japan Really a Low-Crime Nation?

2 Is Japan Really a Low-Crime Nation? If we tried to compare the number of cars in Japan with the number of cars in the US we would probably find fairly reliable statistics in this field. Maybe we would have some minor problems concerning differ ences as to what is defined as a 'car' in the two cultures, and maybe differences in registering cars would make our comparisons a little bit uncertain. Nevertheless, cars are physical and identifiable objects that are officially registered. Consequently, it should be fairly easy to determine the density of cars in those two countries, and we could properly talk about 'facts' in this connection. The problem of objective fact is more complicated, to say the least, if we want to compare crime rates. Everybody knows that most types of statistics lie. Crime statistics lie even more. This means that the assertion of little crime in Japan cannot be taken as a given fact, but is something that has to be discussed. Is Japan really a low-crime nation? Let me make this statement very clear at the outset: there is no 'correct' answer to this question. Even though I will argue that Japan for a long period after the Second World War should be described as unique for showing little crime, it would be presumptuous to give the impression that this is an unequivocal fact comparable to a statement such as that Japan is a 'high density' society with respect to car volume. Crime is not a physical object (like the car) but a social construction. -

The Legalization of Hinomaru and Kimigayo As Japan's National Flag

The legalization of Hinomaru and Kimigayo as Japan's national flag and anthem and its connections to the political campaign of "healthy nationalism and internationalism" Marit Bruaset Institutt for østeuropeiske og orientalske studier, Universitetet i Oslo Vår 2003 Introduction The main focus of this thesis is the legalization of Hinomaru and Kimigayo as the national flag and anthem of Japan in 1999 and its connections to what seems to be an atypical Japanese form of postwar nationalism. In the 1980s a campaign headed by among others Prime Minister Nakasone was promoted to increase the pride of the Japanese in their nation and to achieve a “transformation of national consciousness”.1 Its supporters tended to use the term “healthy nationalism and internationalism”. When discussing the legalization of Hinomaru and Kimigayo as the national flag and anthem of Japan, it is necessary to look into the nationalism that became evident in the 1980s and see to what extent the legalization is connected with it. Furthermore we must discuss whether the legalization would have been possible without the emergence of so- called “healthy nationalism and internationalism”. Thus it is first necessary to discuss and try to clarify the confusing terms of “healthy nationalism and patriotism”. Secondly, we must look into why and how the so-called “healthy nationalism and internationalism” occurred and address the question of why its occurrence was controversial. The field of education seems to be the area of Japanese society where the controversy regarding its occurrence was strongest. The Ministry of Education, Monbushō, and the Japan Teachers' Union, Nihon Kyōshokuin Kumiai (hereafter Nikkyōso), were the main opponents struggling over the issue of Hinomaru, and especially Kimigayo, due to its lyrics praising the emperor. -

Civil Society and the State in Democratic East Asia

PROTEST AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS Chiavacci, (eds) Grano & Obinger Civil Society and the State in Democratic East Asia East Democratic in State the and Society Civil Edited by David Chiavacci, Simona Grano, and Julia Obinger Civil Society and the State in Democratic East Asia Between Entanglement and Contention in Post High Growth Civil Society and the State in Democratic East Asia Protest and Social Movements Recent years have seen an explosion of protest movements around the world, and academic theories are racing to catch up with them. This series aims to further our understanding of the origins, dealings, decisions, and outcomes of social movements by fostering dialogue among many traditions of thought, across European nations and across continents. All theoretical perspectives are welcome. Books in the series typically combine theory with empirical research, dealing with various types of mobilization, from neighborhood groups to revolutions. We especially welcome work that synthesizes or compares different approaches to social movements, such as cultural and structural traditions, micro- and macro-social, economic and ideal, or qualitative and quantitative. Books in the series will be published in English. One goal is to encourage non- native speakers to introduce their work to Anglophone audiences. Another is to maximize accessibility: all books will be available in open access within a year after printed publication. Series Editors Jan Willem Duyvendak is professor of Sociology at the University of Amsterdam. James M. Jasper teaches at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. Civil Society and the State in Democratic East Asia Between Entanglement and Contention in Post High Growth Edited by David Chiavacci, Simona Grano, and Julia Obinger Amsterdam University Press Published with the support of the Swiss National Science Foundation. -

Lesbians in Japan and South Korea

Her Story: Lesbians in Japan and South Korea Elise Fylling EAST 4590 – Master’s Thesis in East Asian Studies African and Asian Studies 60 credits – spring 2012 Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages Faculty of Humanities University of Oslo Her Story: Lesbians in Japan and South Korea Master’s thesis, Elise Fylling © Elise Fylling 2012 Her Story: Lesbians in Japan and South Korea Elise Fylling Academic supervisor: Vladimir Tikhonov http://www.duo.uio.no Printed by: Webergs Printshop Summary Lesbians in Japan and South Korea have long been ignored in both academic, and in social context. The assumption that there are no lesbians in Japan or South Korea dominates a large population in these societies, because lesbians do not identify as such in the public domain. Instead they often live double lives showing one side of themselves to the public and another in private. Although there exist no formal laws against homosexuality, a social barrier in relation to coming out to one’s family, friends or co-workers is highly present. Shame, embarrassment and fear of being rejected as deviant or abnormal makes it difficult to step outside of the bonds put on by society’s hetero-normative structures. What is it like to be lesbian in contemporary Japan and South Korea? In my dissertation I look closely at the Japanese and South Korean society’s attitudes towards young lesbians, examining their experiences concerning identity, invisibility, family relations, the question of marriage and how they see themselves in society. I also touch upon how they meet others in spite of their invisibility as well as giving some insight to the way they chose to live their life. -

The Burakumin Myth of Everyday Life: Reformulating Identity In

From Subnational to Micronational: Buraku Communities and Transformations in Identity in Modern and Contemporary Japan Rositsa Mutafchieva East Asian Studies McGill University, Montreal April 2009 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the PhD degree © Rositsa Mutafchieva 2009 1 Table of Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................... 3 Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................... 5 Introduction: Burakumin: A Minority in Flux ............................................................ 8 Chapter One: Moments in the History of Constructing Outcast Spaces ......... 19 Chapter Two: Three Buraku Communitiees, Three Different Stories ............... 52 Chapter Three: Instructions Given: ―Building a Nation = Building a Community‖ .............................................................................................................. 112 Chapter Four: The Voices of the Buraku ............................................................. 133 Chapter Five: ―Community Building‖ Revisited................................................... 157 Conclusion ................................................................................................................ 180 Appendix ................................................................................................................... 192 Bibliography............................................................................................................. -

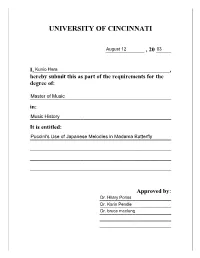

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI _____________ , 20 _____ I,______________________________________________, hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: ________________________________________________ in: ________________________________________________ It is entitled: ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ Approved by: ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ PUCCINI’S USE OF JAPANESE MELODIES IN MADAMA BUTTERFLY A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2003 by Kunio Hara B.M., University of Cincinnati, 2000 Committee Chair: Dr. Hilary Poriss ABSTRACT One of the more striking aspects of exoticism in Puccini’s Madama Butterfly is the extent to which the composer incorporated Japanese musical material in his score. From the earliest discussion of the work, musicologists have identified many Japanese melodies and musical characteristics that Puccini used in this work. Some have argued that this approach indicates Puccini’s preoccupation with creating an authentic Japanese setting within his opera; others have maintained that Puccini wanted to produce an exotic atmosphere