ANTIQUE APPLES for MODERN ORCHARDS Ian A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apples Catalogue 2019

ADAMS PEARMAIN Herefordshire, England 1862 Oct 15 Nov Mar 14 Adams Pearmain is a an old-fashioned late dessert apple, one of the most popular varieties in Victorian England. It has an attractive 'pearmain' shape. This is a fairly dry apple - which is perhaps not regarded as a desirable attribute today. In spite of this it is actually a very enjoyable apple, with a rich aromatic flavour which in apple terms is usually described as Although it had 'shelf appeal' for the Victorian housewife, its autumnal colouring is probably too subdued to compete with the bright young things of the modern supermarket shelves. Perhaps this is part of its appeal; it recalls a bygone era where subtlety of flavour was appreciated - a lovely apple to savour in front of an open fire on a cold winter's day. Tree hardy. Does will in all soils, even clay. AERLIE RED FLESH (Hidden Rose, Mountain Rose) California 1930’s 19 20 20 Cook Oct 20 15 An amazing red fleshed apple, discovered in Aerlie, Oregon, which may be the best of all red fleshed varieties and indeed would be an outstandingly delicious apple no matter what color the flesh is. A choice seedling, Aerlie Red Flesh has a beautiful yellow skin with pale whitish dots, but it is inside that it excels. Deep rose red flesh, juicy, crisp, hard, sugary and richly flavored, ripening late (October) and keeping throughout the winter. The late Conrad Gemmer, an astute observer of apples with 500 varieties in his collection, rated Hidden Rose an outstanding variety of top quality. -

APPLE (Fruit Varieties)

E TG/14/9 ORIGINAL: English DATE: 2005-04-06 INTERNATIONAL UNION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NEW VARIETIES OF PLANTS GENEVA * APPLE (Fruit Varieties) UPOV Code: MALUS_DOM (Malus domestica Borkh.) GUIDELINES FOR THE CONDUCT OF TESTS FOR DISTINCTNESS, UNIFORMITY AND STABILITY Alternative Names:* Botanical name English French German Spanish Malus domestica Apple Pommier Apfel Manzano Borkh. The purpose of these guidelines (“Test Guidelines”) is to elaborate the principles contained in the General Introduction (document TG/1/3), and its associated TGP documents, into detailed practical guidance for the harmonized examination of distinctness, uniformity and stability (DUS) and, in particular, to identify appropriate characteristics for the examination of DUS and production of harmonized variety descriptions. ASSOCIATED DOCUMENTS These Test Guidelines should be read in conjunction with the General Introduction and its associated TGP documents. Other associated UPOV documents: TG/163/3 Apple Rootstocks TG/192/1 Ornamental Apple * These names were correct at the time of the introduction of these Test Guidelines but may be revised or updated. [Readers are advised to consult the UPOV Code, which can be found on the UPOV Website (www.upov.int), for the latest information.] i:\orgupov\shared\tg\applefru\tg 14 9 e.doc TG/14/9 Apple, 2005-04-06 - 2 - TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. SUBJECT OF THESE TEST GUIDELINES..................................................................................................3 2. MATERIAL REQUIRED ...............................................................................................................................3 -

Apple Varieties in Maine Frederick Charles Bradford

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library 6-1911 Apple Varieties in Maine Frederick Charles Bradford Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Agriculture Commons Recommended Citation Bradford, Frederick Charles, "Apple Varieties in Maine" (1911). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2384. http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/2384 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of Maine in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN AGRICULTURE by FREDERICK CHARLES BRADFORD, B. S . Orono, Maine. June, 1911. 8 2 8 5 INTRODUCTION The following pages represent an effort to trace the causes of the changing procession of varieties of apples grown in Maine. To this end the history of fruit growing in Maine has been carefully studied, largely through the Agricultural Reports from 1850 to 1909 and the columns of the Maine Farmer fran 1838 to 1875. The inquiry has been confined as rigidly as possible to this state, out side sources being referred to only for sake of compari son. Rather incidentally, soil influences, modifications due to climate, etc., have been considered. Naturally* since the inquiry was limited to printed record, nothing new has been discovered in this study. Perhaps a somewhat new point of view has been achieved. And, since early Maine pomological literature has been rather neglected by our leading writers, some few forgot ten facts have been exhumed. -

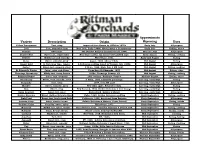

Variety Description Origin Approximate Ripening Uses

Approximate Variety Description Origin Ripening Uses Yellow Transparent Tart, crisp Imported from Russia by USDA in 1870s Early July All-purpose Lodi Tart, somewhat firm New York, Early 1900s. Montgomery x Transparent. Early July Baking, sauce Pristine Sweet-tart PRI (Purdue Rutgers Illinois) release, 1994. Mid-late July All-purpose Dandee Red Sweet-tart, semi-tender New Ohio variety. An improved PaulaRed type. Early August Eating, cooking Redfree Mildly tart and crunchy PRI release, 1981. Early-mid August Eating Sansa Sweet, crunchy, juicy Japan, 1988. Akane x Gala. Mid August Eating Ginger Gold G. Delicious type, tangier G Delicious seedling found in Virginia, late 1960s. Mid August All-purpose Zestar! Sweet-tart, crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1999. State Fair x MN 1691. Mid August Eating, cooking St Edmund's Pippin Juicy, crisp, rich flavor From Bury St Edmunds, 1870. Mid August Eating, cider Chenango Strawberry Mildly tart, berry flavors 1850s, Chenango County, NY Mid August Eating, cooking Summer Rambo Juicy, tart, aromatic 16th century, Rambure, France. Mid-late August Eating, sauce Honeycrisp Sweet, very crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1991. Unknown parentage. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Burgundy Tart, crisp 1974, from NY state Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Blondee Sweet, crunchy, juicy New Ohio apple. Related to Gala. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Gala Sweet, crisp New Zealand, 1934. Golden Delicious x Cox Orange. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Swiss Gourmet Sweet-tart, juicy Switzerland. Golden x Idared. Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Golden Supreme Sweet, Golden Delcious type Idaho, 1960. Golden Delicious seedling Early September Eating, cooking Pink Pearl Sweet-tart, bright pink flesh California, 1944, developed from Surprise Early September All-purpose Autumn Crisp Juicy, slow to brown Golden Delicious x Monroe. -

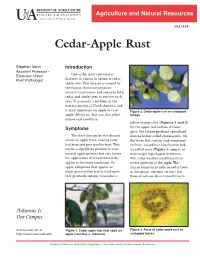

Cedar-Apple Rust

DIVISION OF AGRICULTURE RESEARCH & EXTENSION Agriculture and Natural Resources University of Arkansas System FSA7538 Cedar-Apple Rust Stephen Vann Introduction Assistant Professor One of the most spectacular Extension Urban Plant Pathologist diseases to appear in spring is cedar- apple rust. This disease is caused by the fungus Gymnosporangium juniperi-virginianae and requires both cedar and apple trees to survive each year. It is mainly a problem in the eastern portion of North America and is most important on apple or crab Figure 2. Cedar-apple rust on crabapple apple (Malus sp), but can also affect foliage. quince and hawthorn. yellow-orange color (Figures 1 and 2). Symptoms On the upper leaf surface of these spots, the fungus produces specialized The chief damage by this disease fruiting bodies called spermagonia. On occurs on apple trees, causing early the lower leaf surface (and sometimes leaf drop and poor quality fruit. This on fruit), raised hair-like fruiting bod can be a significant problem to com ies called aecia (Figure 3) appear as mercial apple growers but also harms microscopic cup-shaped structures. the appearance of ornamental crab Wet, rainy weather conditions favor apples in the home landscape. On severe infection of the apple. The apple, symptoms first appear as fungus forms large galls on cedar trees small green-yellow leaf or fruit spots in the spring (see next section), but that gradually enlarge to become a these structures do not greatly harm Arkansas Is Our Campus Visit our web site at: Figure 1. Cedar-apple rust (leaf spot) on Figure 3. Aecia of cedar-apple rust on https://www.uaex.uada.edu apple (courtesy J. -

Apples: Organic Production Guide

A project of the National Center for Appropriate Technology 1-800-346-9140 • www.attra.ncat.org Apples: Organic Production Guide By Tammy Hinman This publication provides information on organic apple production from recent research and producer and Guy Ames, NCAT experience. Many aspects of apple production are the same whether the grower uses low-spray, organic, Agriculture Specialists or conventional management. Accordingly, this publication focuses on the aspects that differ from Published nonorganic practices—primarily pest and disease control, marketing, and economics. (Information on March 2011 organic weed control and fertility management in orchards is presented in a separate ATTRA publica- © NCAT tion, Tree Fruits: Organic Production Overview.) This publication introduces the major apple insect pests IP020 and diseases and the most effective organic management methods. It also includes farmer profiles of working orchards and a section dealing with economic and marketing considerations. There is an exten- sive list of resources for information and supplies and an appendix on disease-resistant apple varieties. Contents Introduction ......................1 Geographical Factors Affecting Disease and Pest Management ...........3 Insect and Mite Pests .....3 Insect IPM in Apples - Kaolin Clay ........6 Diseases ........................... 14 Mammal and Bird Pests .........................20 Thinning ..........................20 Weed and Orchard Floor Management ......20 Economics and Marketing ........................22 Conclusion -

Fruit Varieties in Nantwich Community Orchard May 2021 Apples

Fruit varieties in Nantwich Community Orchard May 2021 Text and photographs by Malcolm Reid The orchard was established in 2008 and now consists of forty-five trees, including twenty-six apple varieties, some of which are long-established cultivars, and a few particular to Cheshire. There are also three varieties of pear tree and three different sorts of plum tree. The information on the trees and their fruit was mainly produced using the following sources: A Guide to the Orchard and Kitchen Garden by George Lindley, edited by John Lindley, 1831 The Book of Apples by Joan Morgan and Alison Richards, 1993 The Apple Book by Rosie Sanders, 2010 The National Fruit Collection database http://www.nationalfruitcollection.org.uk/ Details from Elizabeth Falding of the fruit trees propagated by Tony Gentil All the photographs were taken in the community orchard. Apples Arthur W Barnes Culinary (cooking) apple This variety of apple tree was first cultivated in 1902 by NF Barnes and is named after his son, who was killed during the First World War. NF Barnes was the head gardener at the Duke of Westminster’s estate at Eaton Hall, near Chester. The apples are best picked in mid-September when they have turned red. They cook well, making a juicy, lemon coloured purée, with plenty of bite and flavour. Ashmead's Kernel Dessert (eating) apple Although this type of tree was first grown by Dr Ashmead, in Gloucestershire, in about 1700, it was not until the mid-19th century that it became widely planted in England. The fruits are best picked in early October when they have a yellowish-green, brown, and orange-red appearance. -

A Manual Key for the Identification of Apples Based on the Descriptions in Bultitude (1983)

A MANUAL KEY FOR THE IDENTIFICATION OF APPLES BASED ON THE DESCRIPTIONS IN BULTITUDE (1983) Simon Clark of Northern Fruit Group and National Orchard Forum, with assistance from Quentin Cleal (NOF). This key is not definitive and is intended to enable the user to “home in” rapidly on likely varieties which should then be confirmed in one or more of the manuals that contain detailed descriptions e.g. Bunyard, Bultitude , Hogg or Sanders . The varieties in this key comprise Bultitude’s list together with some widely grown cultivars developed since Bultitude produced his book. The page numbers of Bultitude’s descriptions are included. The National Fruit Collection at Brogdale are preparing a list of “recent” varieties not included in Bultitude(1983) but which are likely to be encountered. This list should be available by late August. As soon as I receive it I will let you have copy. I will tabulate the characters of the varieties so that you can easily “slot them in to” the key. Feedback welcome, Tel: 0113 266 3235 (with answer phone), E-mail [email protected] Simon Clark, August 2005 References: Bultitude J. (1983) Apples. Macmillan Press, London Bunyard E.A. (1920) A Handbook of Hardy Fruits; Apples and Pears. John Murray, London Hogg R. (1884) The Fruit Manual. Journal of the Horticultural Office, London. Reprinted 2002 Langford Press, Wigtown. Sanders R. (1988) The English Apple. Phaidon, Oxford Each variety is categorised as belonging to one of eight broad groups. These groups are delineated using skin characteristics and usage i.e. whether cookers, (sour) or eaters (sweet). -

Handling of Apple Transport Techniques and Efficiency Vibration, Damage and Bruising Texture, Firmness and Quality

Centre of Excellence AGROPHYSICS for Applied Physics in Sustainable Agriculture Handling of Apple transport techniques and efficiency vibration, damage and bruising texture, firmness and quality Bohdan Dobrzañski, jr. Jacek Rabcewicz Rafa³ Rybczyñski B. Dobrzañski Institute of Agrophysics Polish Academy of Sciences Centre of Excellence AGROPHYSICS for Applied Physics in Sustainable Agriculture Handling of Apple transport techniques and efficiency vibration, damage and bruising texture, firmness and quality Bohdan Dobrzañski, jr. Jacek Rabcewicz Rafa³ Rybczyñski B. Dobrzañski Institute of Agrophysics Polish Academy of Sciences PUBLISHED BY: B. DOBRZAŃSKI INSTITUTE OF AGROPHYSICS OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES ACTIVITIES OF WP9 IN THE CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE AGROPHYSICS CONTRACT NO: QLAM-2001-00428 CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE FOR APPLIED PHYSICS IN SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE WITH THE th ACRONYM AGROPHYSICS IS FOUNDED UNDER 5 EU FRAMEWORK FOR RESEARCH, TECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT AND DEMONSTRATION ACTIVITIES GENERAL SUPERVISOR OF THE CENTRE: PROF. DR. RYSZARD T. WALCZAK, MEMBER OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES PROJECT COORDINATOR: DR. ENG. ANDRZEJ STĘPNIEWSKI WP9: PHYSICAL METHODS OF EVALUATION OF FRUIT AND VEGETABLE QUALITY LEADER OF WP9: PROF. DR. ENG. BOHDAN DOBRZAŃSKI, JR. REVIEWED BY PROF. DR. ENG. JÓZEF KOWALCZUK TRANSLATED (EXCEPT CHAPTERS: 1, 2, 6-9) BY M.SC. TOMASZ BYLICA THE RESULTS OF STUDY PRESENTED IN THE MONOGRAPH ARE SUPPORTED BY: THE STATE COMMITTEE FOR SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH UNDER GRANT NO. 5 P06F 012 19 AND ORDERED PROJECT NO. PBZ-51-02 RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF POMOLOGY AND FLORICULTURE B. DOBRZAŃSKI INSTITUTE OF AGROPHYSICS OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES ©Copyright by BOHDAN DOBRZAŃSKI INSTITUTE OF AGROPHYSICS OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES LUBLIN 2006 ISBN 83-89969-55-6 ST 1 EDITION - ISBN 83-89969-55-6 (IN ENGLISH) 180 COPIES, PRINTED SHEETS (16.8) PRINTED ON ACID-FREE PAPER IN POLAND BY: ALF-GRAF, UL. -

Know Your · a S

MAGR Extension Folder 177 GOVS Revised October 1957 MN 2000 EF-no.177 (Rev.1957:0ct.) Know Your · A s by ELEANOR LOOMIS .,~I UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA Agricultural Extension Service U. S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Know Your Minnesota Apples Variety Season of use Characteristics Use Oriole August Large summer apple, orange-yellow, striped with Dessert, pie, sauce, freezing red. Very good eating and cooking quality. Duchess August-September Early, cooking apple. Medium size, striped with Pie, sauce, jelly, freezing red. Too tart for good eating. Beacon August-September Medium size, very attractive red. Mild subacid. Dessert, pie, sauce, freezing Better for eating than Duchess; keeps longer. Wealthy September-November Long a favorite in Minnesota for eating and cook Dessert, baking, pie, sauce, ing. Medium size, striped red. jelly, freezing Lakeland September-December Medium size, solid red color, pleasant flavor. Slices Dessert, pie, baking, sauce, hold shape when cooked. freezing Minjon September-December Below medium size, very attractive red. Flesh Dessert, pie, baking, sauce, somewhat tart, stained with red. freezing McIntosh October-January Medium size, nearly solid bright red. High quality Dessert, pie, sauce, jelly, for eating. Rich flavor, but soft when cooked. freezing Cortland October-January Medium size, attractive red; white flesh similar Dessert, pie, baking, sauce, to McIntosh. Holds fresh color well in salad. jelly, salad, freezing Redwell October-January Large size, attractive red. Pleasant flavor, subacid. Dessert, baking, sauce Jonathan October-February Below medium size, solid bright red. A favorite Dessert, pie, baking, sauce, variety for all uses. jelly, canning, freezing Haralson October-March Medium size, attractive red. -

Effect of Cultivar, Position of Fruits in Tree-Crown and of Summer Pruning on Surface Temperature of Apples and Pears, Ejpau, 15(2), #03

Electronic Journal of Polish Agricultural Universities (EJPAU) founded by all Polish Agriculture Universities presents original papers and review articles relevant to all aspects of agricultural sciences. It is target for persons working both in science and industry, regulatory agencies or teaching in agricultural sector. Covered by IFIS Publishing (Food Science and Technology Abstracts), ELSEVIER Science - Food Science and Technology Program, CAS USA (Chemical Abstracts), CABI Publishing UK and ALPSP (Association of Learned and Professional Society Publisher - full membership). Presented in the Master List of Thomson ISI. ELECTRONIC 2012 JOURNAL Volume 15 OF POLISH Issue 2 AGRICULTURAL Topic HORTICULTURE UNIVERSITIES Copyright © Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Przyrodniczego we Wrocławiu, ISSN 1505-0297 LIPA T., LIPECKI J., JANISZ A., 2012. EFFECT OF CULTIVAR, POSITION OF FRUITS IN TREE-CROWN AND OF SUMMER PRUNING ON SURFACE TEMPERATURE OF APPLES AND PEARS, EJPAU, 15(2), #03. Available Online http://www.ejpau.media.pl EFFECT OF CULTIVAR, POSITION OF FRUITS IN TREE-CROWN AND OF SUMMER PRUNING ON SURFACE TEMPERATURE OF APPLES AND PEARS Tomasz Lipa, Janusz Lipecki, Anna Janisz Departament of Pomology, University of Life Sciences in Lublin, Poland ABSTRACT Extensive studies (2006–2009) on the influence of apple and pear fruit surface temperature, in dependence on the fruit position in tree canopy and summer pruning, were conducted in a commercial orchard in Lublin district, Poland. There was a significant effect of fruit position in the canopy on heat accumulation in fruit surface. Fruits born in southern part of the canopy were more heated than those from other tree parts. It was found that a blush contributed to an increase of fruit temperature, especially those from southern parts of the canopy. -

The Craft Cider Revival – Some Technical Considerations Andrew Lea 28/2/2007 1

The Craft Cider Revival – Some Technical Considerations Andrew Lea 28/2/2007 1 THE CRAFT CIDER REVIVAL ~ Some Technical Considerations Presentation to SWECA 28th February 2007 Andrew Lea SOME THINGS TO THINK ABOUT Orcharding and fruit selection Full juice or high gravity fermentations Yeast and sulphiting Keeving Malo-lactic maturation Style of finished product What is your overall USP? How are you differentiated? CRAFT CIDER IS NOW SPREADING Cidermaking was once widespread over the whole of Southern England There are signs that it may be returning eg Kent, Sussex and East Anglia So regional styles may be back in favour eg higher acid /less tannic in the East CHOICE OF CIDER FRUIT The traditional classification (Barker, LARS, 1905) Acid % ‘Tannin’ % Sweet < 0.45 < 0.2 Sharp > 0.45 < 0.2 Bittersharp > 0.45 > 0.2 Bittersweet < 0.45 > 0.2 Finished ~ 0.45 ~ 0.2 Cider CHOICE OF “VINTAGE QUALITY” FRUIT Term devised by Hogg 1886 Adopted by Barker 1910 to embrace superior qualities that could not be determined by analysis This is still true today! The Craft Cider Revival – Some Technical Considerations Andrew Lea 28/2/2007 2 “VINTAGE QUALITY” LIST (1988) Sharps / Bittersharps Dymock Red Kingston Black Stoke Red Foxwhelp Browns Apple Frederick Backwell Red Bittersweets Ashton Brown Jersey Harry Masters Jersey Dabinett Major White Jersey Yarlington Mill Medaille d’Or Pure Sweets Northwood Sweet Alford Sweet Coppin BLENDING OR SINGLE VARIETALS? Blending before fermentation can ensure good pH control (< 3.8) High pH (bittersweet) juices prone to infection Single varietals may be sensorially unbalanced unless ameliorated with dilution or added acid RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN pH AND TITRATABLE ACID IS NOT EXACT Most bittersweet juices are > pH 3.8 or < 0.4% titratable acidity.