The Gray Market: Why Freeports Don't Deserve

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863)

1/44 Data Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) Pays : France Langue : Français Sexe : Masculin Naissance : Saint-Maurice (Val-de-Marne), 26-04-1798 Mort : Paris (France), 13-08-1863 Activité commerciale : Éditeur Note : Peintre, aquarelliste, graveur et lithographe Domaines : Peinture Autres formes du nom : Ferdinand-Victor-Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) Delacroix (1798-1863) Dorakurowa (1798-1863) (japonais) 30 30 30 30 30 C9 E9 AF ED EF (1798-1863) (japonais) ISNI : ISNI 0000 0001 2098 8878 (Informations sur l'ISNI) Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) : œuvres (416 ressources dans data.bnf.fr) Œuvres iconographiques (312) Hamlet Étude pour les Femmes d'Alger (1837) (1833) Faust (1825) Voir plus de documents de ce genre Œuvres textuelles (80) Journal "Hamlet" (1822) (1600) de William Shakespeare avec Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) comme Illustrateur Voir plus de documents de ce genre data.bnf.fr 2/44 Data Œuvres des beaux-arts et des arts décoratifs (11) Lutte de Jacob avec l'Ange Héliodore chassé du temple (1855) (1855) La chasse aux lions Prise de Constantinople par les croisés : 1840 (1855) (1840) Médée furieuse La bataille de Taillebourg 21 juillet 1242 (1838) (1837) Femmes d'Alger dans leur appartement La bataille de Nancy, mort du duc de Bourgogne, (1834) Charles le Téméraire (1831) La liberté guidant le peuple La mort de Sardanapale (1830) (1827) Dante et Virgile aux Enfers (1822) Manuscrits et archives (13) "DELACROIX (Eugène), peintre, membre de l'Institut. "Cavalier arabe tenant son cheval par la bride, par (NAF 28420 (53))" -

Dark Side of the Boom

dark side of the boom The Excesses of the Art Market in the Twenty-first Century Georgina Adam dark side of the boom First published in 2017 by Lund Humphries Office 3, 261a City Road London ec1v 1jx UK www.lundhumphries.com Copyright © 2017 Georgina Adam isbn Paperback: 978-1-84822-220-5 isbn eBook (PDF): 978-1-84822-221-2 isbn eBook (ePUB): 978-1-84822-222-9 isbn eBook (ePUB Mobi): 978-1-84822-223-6 A Cataloguing-in-Publication record for this book is available from the British Library. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise, without first seeking the permission of the copyright owners and publishers. Every effort has been made to seek permission to reproduce the images in this book. Any omissions are entirely unintentional, and details should be addressed to the publishers. Georgina Adam has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the Author of this Work. Designed by Crow Books Printed and bound in Slovenia Cover: artwork entitled $ made from reflector caps, lamps and an electronic sequencer, by Tim Noble and Sue Webster and One Dollar Bills, 1962 and Two Dollar Bills by Andy Warhol, hang on a wall at Sotheby’s in London on June 8, 2015. Photo: Adrian Dennis/AFP/Getty Images. For Amelia, Audrey, Isabella, Matthew, Aaron and Lucy Contents Introduction 9 Prologue: Le Freeport, Luxembourg 17 PART I: Sustaining the Big Bucks market 25 1 Supply 27 2 Demand: China Wakes 51 Part II: A Fortune on your Wall? 69 3 What’s the Price? 71 4 The Problems with Authentication 89 5 A Tsunami of Forgery 107 Part IiI: Money, Money, Money 127 6 Investment 129 7 Speculation 149 8 The Dark Side 165 Postscript 193 Appendix 197 Notes 199 Bibliography 223 Index 225 introduction When my first book, Big Bucks, the Explosion of the Art Market in the 21st Century, was published in 2014 the art market was riding high. -

1 How Modern Art Serves the Rich by Rachel Wetzler the New Republic

1 How Modern Art Serves the Rich By Rachel Wetzler The New Republic, February 26, 2018 During the late 1950s and 1960s, Robert and Ethel Scull, owners of a lucrative taxi company, became fixtures on the New York gallery circuit, buying up the work of then-emerging Abstract Expressionist, Minimalist, and Pop artists in droves. Described by Tom Wolfe as “the folk heroes of every social climber who ever hit New York”—Robert was a high school drop-out from the Bronx—the Sculls shrewdly recognized that establishing themselves as influential art collectors offered access to the upper echelons of Manhattan society in a way that nouveau riche “taxi tycoon” did not. Then, on October 18, 1973, in front of a slew of television cameras and a packed salesroom at the auction house Sotheby Parke Bernet, they put 50 works from their collection up for sale, ultimately netting $2.2 million—an unheard of sum for contemporary American art. More spectacular was the disparity between what the Sculls had initially paid, in some cases only a few years prior to the sale, and the prices they commanded at auction: A painting by Cy Twombly, originally purchased for $750, went for $40,000; Jasper Johns’s Double White Map, bought in 1965 for around $10,000, sold for $240,000. Robert Rauschenberg, who had sold his 1958 work Thaw to the Sculls for $900 and now saw it bring in $85,000, infamously confronted Robert Scull after the sale, shoving the collector and accusing him of exploiting artists’ labor. In a scathing essay published the following month in New York magazine, titled “Profit Without Honor,” the critic Barbara Rose described the sale as the moment “when the art world collapsed.” In retrospect, the Sculls’ auction looks more like the beginning than the end. -

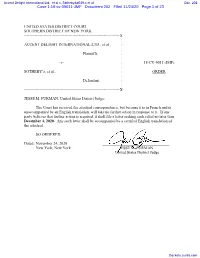

ORDER. the Court Has Received the Attached Correspondence, But

Accent Delight International Ltd. et al v. Sotheby's et al Doc. 202 Case 1:18-cv-09011-JMF Document 202 Filed 11/24/20 Page 1 of 23 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ------------------------------------------------------------------------- X : ACCENT DELIGHT INTERNATIONAL LTD., et al., : : Plaintiffs, : : -v- : 18-CV-9011 (JMF) : SOTHEBY’s, et al., : ORDER : Defendant. : : ------------------------------------------------------------------------- X JESSE M. FURMAN, United States District Judge: The Court has received the attached correspondence, but because it is in French and is unaccompanied by an English translation, will take no further action in response to it. If any party believes that further action is required, it shall file a letter seeking such relief no later than December 4, 2020. Any such letter shall be accompanied by a certified English translation of the attached. SO ORDERED. Dated: November 24, 2020 __________________________________ New York, New York JESSE M. FURMAN United States District Judge Dockets.Justia.com Case 1:18-cv-09011-JMF Document 202 Filed 11/24/20 Page 2 of 23 Republique et canton de Geneve Geneve, le 1er octobre 2020 POUVOIR JUDICIAIRE Tribunal civil CR/14/2020 2 COO XCR Tribunal de premiere instance Rue de l'Athenee 6-8 !A-PRIORITY! Case postale 3736 CH - 1211 GENEVE 3 R II II IIIIIIIII II IIIIII Ill 1111111111111111111 Avis de reception R P371 89506 7 CH Please scan - Signature required Veuillez scanner- Remlse contre signature UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURTFORTHESOUTHEM DISTRICT NY Honorable Jesse M. Furman 40 Centre Street, Room 2202 10007 New York NY ETATS-U.NIS Ref : CR/14/2020 2 COO XCR a rappeler !ors de toute communication Votre ref: 1 :18-CV-09+011-JMF-RWL Nous vous remettons ci-joint copie de l'ordonnance dans la cause mention nee sous rubrique. -

Monaco 2020 Human Rights Report

MONACO 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Principality of Monaco is a constitutional monarchy in which the sovereign prince plays the leading governmental role. The prince appoints the government, which consists of a minister of state and five ministers. The prince shares the country’s legislative power with the popularly elected National Council, which is elected every five years. Multiparty elections for the National Council in 2018 were considered free and fair. The national police are responsible for maintaining public order and the security of persons and property. The Palace Guard is responsible for the security of the prince, the royal family, and their property. Both report to the Ministry of Interior. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security forces. There were no reports security forces committed abuses. Significant human rights issues included the existence of criminal libel laws. The country had mechanisms in place to identify and punish officials who may commit human rights abuses. Section 1. Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom from: a. Arbitrary Deprivation of Life and Other Unlawful or Politically Motivated Killings There were no reports that the government or its agents committed arbitrary or unlawful killings. The Inspection Generale des Services de Police of the Ministry of Interior is responsible for investigating whether any killings carried out by security forces were justifiable. b. Disappearance There were no reports of disappearances by or on behalf of government authorities. c. Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment MONACO 2 The constitution and law prohibit such practices, and there were no reports that government officials employed them. -

Accent Delight Int'l Ltd. V. Sotheby's

Accent Delight International Ltd. et al v. Sotheby's et al Doc. 205 &DVHFY-0)'RFXPHQW)LOHG3DJHRI UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ---------------------------------------------------------------------- X : ACCENT DELIGHT INTERNATIONAL LTD., et al., : : Plaintiffs, : : 18-CV-9011 (JMF) -v- : : OPINION AND ORDER 627+(%<¶6et al., : : Defendants. : : ---------------------------------------------------------------------- X JESSE M. FURMAN, United States District Judge: The question presented here ² which has spawned surprisingly little and, in this Circuit at least, conflicting law ² is whether a party seeking to discover materials relating to a private confidential mediation must satisfy a heightened standard of need. The question arises in a lawsuit between Plaintiffs Accent Delight International Ltd. and Xitrans Finance Ltd. and 'HIHQGDQWV6RWKHE\¶VDQG6RWKHE\¶V,QF FROOHFWLYHO\³6RWKHE\¶V´ RYHU6RWKHE\¶VUROHLQan alleged scheme by Yves Bouvier, an art dealer who is not a party to this case, to defraud Plaintiffs of approximately one billion dollars in connection with the purchase of a world-class art collection, including Leonardo da 9LQFL¶VChrist as Salvator Mundi. In a private mediation subject to an agreement of confidentiality, 6RWKHE\¶VVHWWOHGseparate litigation with the original sellers of Salvator Mundi, and Plaintiffs here now move to compel disclosure of materials relating to that mediation. For the reasons that follow, the Court holds that a heightened standard does apply to that request and that Plaintiffs fail to satisfy it. Accordingly, the motion is denied. BACKGROUND The Court has LVVXHGPDQ\RSLQLRQVLQFRQQHFWLRQZLWK3ODLQWLIIV¶FODLPVDJDLQVW 6RWKHE\¶VDQG%RXYLHU in this and a related case, familiarity with which is presumed. See, e.g., Dockets.Justia.com &DVHFY-0)'RFXPHQW)LOHG3DJHRI $FFHQW'HOLJKW,QW¶O/WGY6RWKHE\¶V, 394 F. -

A Freeport Comes to Luxembourg, Or, Why Those Wishing to Hide Assets Purchase Fine Art

arts Article A Freeport Comes to Luxembourg, or, Why Those Wishing to Hide Assets Purchase Fine Art Samuel Weeks College of Humanities and Sciences, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA 19144, USA; samuel.weeks@jefferson.edu Received: 4 June 2020; Accepted: 4 August 2020; Published: 9 August 2020 Abstract: This article addresses how global art markets are becoming an outlet of choice for those wishing to hide assets. Recent efforts by the OECD and the U.S. Treasury have made it more difficult for people to avoid taxes by taking money “offshore”. These efforts, however, do not cover physical assets such as fine art. Citing data collected in Luxembourg—a jurisdiction angling to become a worldwide leader in “art finance”—I discuss the characteristics of this emerging system of opaque economic activity. The first of these is a “freeport”, a luxurious and securitized warehouse where investors can store, buy, and sell art tax free with minimal oversight. The second element points to the work of art-finance professionals, who issue loans using fine art as collateral and develop “art funds” linked to the market value of certain artworks. The final elements cover lax scrutiny by enforcement authorities as well as the secrecy techniques typically on offer in offshore centers. Combining these elements in jurisdictions such as Luxembourg can make mobile and secret the vast wealth stored in fine art. I end the article by asking whether artworks linked to freeports and opaque financial products have become the contemporary version of the numbered Swiss bank account or the suitcase full of cash. -

Singapore Judgments

This judgment is subject to final editorial corrections approved by the court and/or redaction pursuant to the publisher’s duty in compliance with the law, for publication in LawNet and/or the Singapore Law Reports. Accent Delight International Ltd and another v Bouvier, Yves Charles Edgar and others [2016] SGHC 40 High Court — Suit No 236 of 2015 Summonses No 1763 of 2015 and 1900 of 2015 Lai Siu Chiu SJ 18, 19, 25 August; 15, 16 September 2015; 24 February 2016 Conflict of laws — Forum non conveniens 17 March 2016 Judgment reserved. Lai Siu Chiu SJ: Introduction 1 Yves Charles Edgar Bouvier (“Bouvier”) and Mei Investment Pte Ltd (“the second defendant”) (hereinafter referred to collectively as “the two defendants”) filed Summons No 1763 of 2015 (“Summons 1763”) for a stay of proceedings of Suit No 236 of 2015 (“this Suit”) commenced by Accent Delight International Ltd (“Accent”) and Xitrans Finance Ltd (“Xitrans”) (hereinafter referred to collectively as “the plaintiffs”). A similar application was taken out by the third defendant, Tania Rappo (“Rappo”), in Summons No 1900 of 2015 (“Summons 1900”). Both summonses (hereinafter referred to collectively as “the Summonses”) were heard together by this court. 2 The Summonses were only two of many applications taken out by one or other of the parties since the writ for this Suit was filed on 12 March 2015. Accent Delight International Ltd v Bouvier, Yves Charles Edgar [2016] SGHC 40 Notably, the plaintiffs had on 12 March 2015 also applied for and were granted a worldwide Mareva injunction against the defendants in Summons No 1143 of 2015 (“Summons 1143”). -

Art & Finance Report 2011 Download the Report

® Art & Finance Report 2011. December 2011 ING gives a frame to your Art. As a proud sponsor of the 4th Deloitte Art & Finance Conference, ING Luxembourg is pleased to support your relationship with the world of Arts. For any question regarding our private wealth services, please contact Maxime Weissen. To benefit from our know-how in managing your collection, feel free to contact Annabelle Birnie. Maxime WEISSEN Annabelle BIRNIE Head of Private Banking Director Sponsoring, Wealth Management Art Management & Events ING Luxembourg Certified Valuer Modern T : +352 4499 5850 & Contemporary Art E : [email protected] I : www.ing.lu T : +31 2056 39243 E : [email protected] I : www.ingartcollection.com WWW.ING.LU PRIVATE BANKING 2 Financial Sector Professionals in Luxembourg (FSP) Profile of a high growth sector 3 NEW YORK + DENVER, UNITED STATES THE FINE ART OF GUARANTEEING OWNERSHIP FINE ART VINTAGE AUTOMOBILES RARE BOOKS & MANUSCRIPTS RARE STRINGED INSTRUMENTS OTHER IMPORTANT COLLECTIBLES aristitle.com ARIS is the sole underwriter of ATPI® art title insurance. The ARIS name, logo and ATPI® are U.S. and international trademarks of ARIS. 4 ARIS_Deloitte_ad 2.indd 1 11/21/11 10:29:14 AM Table of contents Foreword 7 Introduction 8 Key findings 9 Priorities 10 Section 1: The art market 12 Section 2: Art as an asset class 17 Section 3: Art and wealth management 26 Section 4: Valuation and risks 35 Section 5: Industry voices 38 Conclusion 45 Appendix 1 46 Appendix 2 52 6 Foreword Deloitte Luxembourg and ArtTactic are pleased to present their inaugural 2011 Art & Finance Report. -

Artcontrecrise Genève,Vaud,Zurich,Bâle

Arts Artcontrecrise Genève,Vaud,Zurich,Bâle Portsfrancs, dédalesetmystères Mercredi 11 novembre 2009 BD:lesbulles Le Temps souslemarteau AntoinedeGalbert, l’hommequivoulaitêtrebrusquéparl’art COURTESY BOB VAN ORSOUW GALLERY, ZURICH Ce supplément ne peut être vendu séparément 2 Arts Le Temps Mercredi 11 novembre 2009 ÉDITO La drôle de crise produit ses au large d’un univers dont ils regroupent pour se donner partie de ceux qui gèrent de grands désastres et ses petits n’ont jamais connu les bien- ce qui manque: des lieux où manière sourcilleuse leur bonheurs. En quelques se- faits. En Suisse, le milieu de exercer leur métier, partager activité. Ses travaux frappent maines, le marché de l’art, l’art paraît peu affecté par les leurs expériences, recevoir le par leur densité, la rigueur de excessivement florissant, s’est turbulences du marché – ou public, voire vendre leurs leur composition, la généro- écroulé. Beaucoup qui collec- alors de manière discrète. A travaux. Les espaces d’art sité de leurs couleurs. Venue tionnaient par ostentation Zurich comme dans la ville qu’ils ouvrent un peu partout d’Iran, établie en Suisse, cette ou à des fins de spéculation rhénane, comme sur les rives ne visent ni l’opulence ni la jeune artiste a fait objet d’une ont rentré leur porte-mon- lémaniques, une relève très prospérité mais d’abord reconnaissance internatio- naie. Les galeries de Manhat- entreprenante s’active et l’échange. Est-ce par refus de nale quasi immédiate. Dans tan ont donc vu disparaître s’organise. L’époque sourit- la forme commerciale? Tout ses images, travaillées avec de nombreux clients. -

The Emergence of New Corporations Free Zones and the Swiss Value Storage Houses

10 The Emergence of New Corporations Free Zones and the Swiss Value Storage Houses Oddný Helgadóttir 10.1 Introduction This chapter introduces the concept of a ‘Luxury Freeport’, positioning such tax- and duty-free storage sites as new players in the ever-evolving ecosystem of the offshore world. To date, Luxury Freeports have largely passed under the radar of academic research and they represent an important lacuna in the academic scholarship on offshore activity. In his state of the art on offshores, The Hidden Wealth of Nations, economist Gabriel Zucman makes this point explicitly, noting that most current estimates of offshore wealth do not extend to non-financial wealth kept in tax havens: This includes yachts registered in the Cayman Islands, as well as works of art, jewelry, and gold stashed in freeports—warehouses that serve as repositories for valuables. Geneva, Luxembourg, and Singapore all have one: in these places, great paintings can be kept and traded tax-free—no customs duty or value-added tax is owed—and anonymously, without ever seeing the light of day. (2015, pp. 44–5) There are no reliable estimates of the value of goods stored in Luxury Freeports.¹ A recent New York Times article reports that art dealers and insurers believe that the works of art contained in the Geneva Freeport, a pioneer in the Luxury Freeport business, would be enough ‘to create one of the world’s great museums’. Similarly, a London-based insurer concludes that there isn’t ‘a piece of paper wide enough to write down all the zeros’ needed to capture the value of wealth stored in Geneva (Segal 2012). -

Ad Can Be Removied

Soon to be implemented in the UK, the 5th Anti- manage their CDD in various scenarios: how, can the dealer go about that when the agent for example, will they respond to a new cli- will wish to keep the identity of their client Art Business Money Laundering Directive looks set to have ent wishing to make an impulse purchase at secret so that they do not get cut out of the a significant impact on the British art market. an art fair. £100 billion transaction? It is hoped the government will AML legislation Art businesses will need systems in place to POCA contains additional offences appli- provide useful guidance to the sector. cable to those in the regulated sector, which will Estimated extent of Auction houses, art dealers, agents and combat money laundering – and they should also become relevant to art-market participants. other art intermediaries need to start planning Sarah Barker already be preparing to meet the new obligations Most notably, if a person working in a business money laundered now and educating themselves in relation to in the regulated sector knows or suspects or has their enhanced obligations. They will likely reasonable grounds for knowing or suspecting that annually through the need to put in place systems and controls and another person is engaged in money laundering adopt comprehensive AML policies. Putting and fails to disclose that to the National Crime UK financial system in place the requisite systems and controls, Agency, then they can commit a crime. (This and then complying with CDD and reporting failure to disclose offence could attract 5 years obligations on an ongoing basis, may be bur- in prison and/or a fine.) This offence includes an densome for the industry.