The Professional Career of African-American Bandmaster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black US Army Bands and Their Bandmasters in World War I

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications: School of Music Music, School of Fall 8-21-2012 Black US Army Bands and Their Bandmasters in World War I Peter M. Lefferts University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub Part of the Music Commons Lefferts, Peter M., "Black US Army Bands and Their Bandmasters in World War I" (2012). Faculty Publications: School of Music. 25. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub/25 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications: School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 1 Version of 08/21/2012 This essay is a work in progress. It was uploaded for the first time in August 2012, and the present document is the first version. The author welcomes comments, additions, and corrections ([email protected]). Black US Army bands and their bandmasters in World War I Peter M. Lefferts This essay sketches the story of the bands and bandmasters of the twenty seven new black army regiments which served in the U.S. Army in World War I. They underwent rapid mobilization and demobilization over 1917-1919, and were for the most part unconnected by personnel or traditions to the long-established bands of the four black regular U.S. Army regiments that preceded them and continued to serve after them. Pressed to find sufficient numbers of willing and able black band leaders, the army turned to schools and the entertainment industry for the necessary talent. -

Perspectives on the American Concert March in Music Education Robert Clark

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Perspectives on the American Concert March in Music Education Robert Clark Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC PERSPECTIVES ON THE AMERICAN CONCERT MARCH IN MUSIC EDUCATION By ROBERT CLARK A Thesis submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Education Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2009 The members of the Committee approve the Thesis of Robert Henry Clark defended on March 30, 2009. __________________________ Steven Kelly Professor Directing Thesis __________________________ Patrick Dunnigan Committee Member __________________________ Christopher Moore Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere appreciation to Dr. Bobby Adams, Jack Crew, Dr. James Croft, Joe Kreines, and Paula Thornton, who freely gave of their time, opinions, teaching methods, and wisdom to make the completion of this research study possible. They were as genuine, engaging, inspiring and generous as I had hoped…and more. It was my pleasure to get to know them all better. I would also like to thank my thesis committee, Dr. Steven Kelly, Dr. Patrick Dunnigan and Dr. Christopher Moore for dedicating the time and effort to review my research. I would especially like to thank Dr. Steven Kelly for his work in helping me refine this study, and am further appreciative to him for the guidance he has provided me throughout my undergraduate and graduate studies. -

Brass Bands of the World a Historical Directory

Brass Bands of the World a historical directory Kurow Haka Brass Band, New Zealand, 1901 Gavin Holman January 2019 Introduction Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 6 Angola................................................................................................................................ 12 Australia – Australian Capital Territory ......................................................................... 13 Australia – New South Wales .......................................................................................... 14 Australia – Northern Territory ....................................................................................... 42 Australia – Queensland ................................................................................................... 43 Australia – South Australia ............................................................................................. 58 Australia – Tasmania ....................................................................................................... 68 Australia – Victoria .......................................................................................................... 73 Australia – Western Australia ....................................................................................... 101 Australia – other ............................................................................................................. 105 Austria ............................................................................................................................ -

1 Don Gillis Interviews William D. Revelli, March 2-7, 1965 American

Don Gillis Interviews William D. Revelli, March 2-7, 1965 American Bandmasters’ Association Research Center, Special Collections in Performing Arts, University of Maryland, College Park Transcription by Christina Taylor Gibson Unknown: Just say something informally and then we’ll go Don Gillis: I think the feature with Bill had a little more . William D. Revelli: Are you hearing me all right in there now? Unknown: And how [mumbling off microphone] W.R.: Is that too much Unknown: No, no it’s fine, it’s normal, just normal. W.R.: Good. That’s all you need, isn’t it? D.G.: I’m talking with William E. Revelli, that is Bill E., William D.? I’ll start over. That’s one of my great blessings, being a good tape editor. I know I can always cut this out. I’m talking to William D. Revelli of the University of Michigan Bands, whose 25th anniversary I had the good fortune to attend. How many years back was this Bill? W.R.: Well, this is … I’m in my thirtieth year now Don. D.G.: Oh, so this was five years ago. W.R.: Yes. D.G.: At the marvelous banquet where we all sat around and tried in some small way to pay tribute to you for what you had done for the band field, not only at the University of Michigan, but it went way back to a town in Indiana named— W.R.: Hobart. D.G.: Hobart, Indiana. Bill, if you don’t mind, on this afternoon to go back about thirty years, why don’t you tell us about what young William Revelli was doing in Hobart, Indiana as a band director in a town that, which started out as an unknown factor and then became known as THE high school band center of the United States after a little while. -

(1921 to 1963) Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

10, /8( D. 0. ("PROF") WILEY: HIS CONTRIBUTIONS TO MUSIC EDUCATION (1921 TO 1963) DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By James I. Hansford, Jr., B.M.Ed., M.M.Ed. Denton, Texas May, 1982 Hansford, James I., Jr., D. 0. ("Prof") Wiley: His Contributions to Music Education (1921 to 1963). Doctor of Philosophy (Music Education), May, 1982, 236 pp., 21 illustrations, Bibliography, 88 titles. The purpose of the study was to write a history of a music educator the professional career of D. 0. Wiley as from 1921 to 1963. To give focus to the career of Wiley, answers were sought to three questions, stated as sub and influ problems: (1) What were the important events ences in the professional career of D. 0. Wiley as a college/university band director? (2) What impact did school Wiley have on the development of Texas public bands that earned him the title "Father of Texas Bands?" of and (3) What role did Wiley play in the development the Texas Music Educators Association and other professional music organizations? D. 0. Wiley was a powerful force in the development as director of public school bands of Texas. While serving of bands at Simmons College (now Hardin-Simmons University) in Abilene, and Texas Tech University in Lubbock, he trained scores of young band directors who accepted teaching positions across the state. Wiley is recognized by the Texas Bandmasters Associa tion as the "Father of Texas Bands," partially because of the large number of his students who became prominent 2 bandmasters and leaders in the professional state music education organizations, but primarily through his pioneer work with the Texas Music Educators Association (TMEA). -

PREVIEW First Section 2

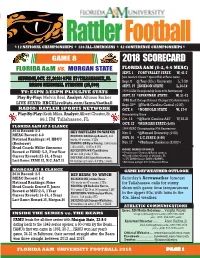

FLORIDA A&M UNIVERSITY / RATTLERS / FOOTBALL Rattler Football * 12 NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS * 130 ALL-AMERICANS * 42 CONFERENCE CHAMPIONSHIPS * GAME 8 2018 SCORECARD FLORIDA A&M vs. MORGAN STATE FLORIDA A&M (5-2, 4-0 MEAC) SEPT. 1 FORT VALLEY STATE W, 41-7 SATURDAY, OCT. 27, 2018 / 4 PM ET / TALLAHASSEE, FL Jake Gaither Classic * Sports Hall of Fame Game Sept. 8 @ Troy (Ala.) University L, 7-59 BRAGG MEMORIAL STADIUM (25,500) SEPT. 15 JACKSON STATE L,16-18 TV: ESPN 3/ESPN PLUS/LIVE STATS 1978 NCAA Championship Team 40th Anniversary Play-By-Play: Melvin Beal. Analyst: Alfonso Barber SEPT. 22 *SAVANNAH STATE W, 31-13 1998 Black College National Champs 20th Anniversary LIVE STATS: HBCULiveStats.com/famu/football Sept. 29 * @North Carolina Central (4:00) RADIO: RATLER SPORTS NETWORK OCT. 6 *NORFOLK STATE W, 17-0 Play-By-Play: Keith Miles. Analyst: Albert Chester, Sr. Homecoming Game 96.1 FM Tallahassee, FL Oct. 13 *@North Carolina A&T W, 22-21 OCT. 27 *MORGAN STATE (4:00) FLORIDA A&M AT A GLANCE 1988 MEAC Championship 30th Anniversary 2018 Record: 5-2 KEY RATTLERS TO WATCH Nov. 3 *@Howard University (1:00) MEAC Record: 4-0 RUSHING: RB Bishop Bonnett, 343 NOV. 10 * S.C.STATE (4:00) National Rankings: #1 HBCU yards, 43 carries, 3 TDs (Boxtorow) PASSING: QB Ryan Stanley, 1,545 yards, Nov. 17 *#Bethune-Cookman (2:00)% Head Coach: Willie Simmons (122 of 202), 10 TDs, 6 INT RECEIVING: WR Chad Hunter HOME GAMES IN BOLD Record at FAMU: 5-2, First Year *Conference Games; @Away games; 32 rec, 446 yards, 5 TDs Career Record: 27-13, 4 Years #Florida Blue Classic at Orlando, FL DEFENSE: LB Elijah Richardson, %-TV ESPNClassic/ESPN3/ESPNU; Last Game: FAMU 22, N.C. -

Ebr Fine Arts Newsletter

VOL. 4|FEBRUARY 2021 Backstage A Monthly Newsletter from EBRPSS Department of Fine Arts 1105 Lee Drive, Building D Baton Rouge, LA 70808 Sean Joffrion, Director of Fine Arts www.ebrfinearts.com Roxi Victorian, Editor 'Science will get us out of this, but the Arts will get us through this' Overview: Art Jazz and Pizazz EBR Student Short Film Festival Forest Heights & Bluebonnet Swamp Center Musical Achievement Linked to Performance in Math & Reading Celebrating BLACK HISTORY MONTH Lessons, Activities & More for K-12 February Tech Bites Celebrations EBRPSS Department of Fine Arts' “Backstage” is our EBR School Community monthly email newsletter celebrating all things Fine Arts in the District. During such an unprecedented time in our global community, Backstage is our attempt to stay connected, informed and united as we push forward during this academic year. We welcome celebrations, and newsworthy events for each issue, and encourage you to send information that you would like highlighted. Each issue includes current and past national news articles highlighting education in the Arts. Thank you for your tireless efforts as Arts Educators. Enjoy this issue! F E B . 2 0 2 1 , V O L . 4 ART, JAZZ, AND The Fine Arts PIZZAZZ: Strollin’ and Department would like Swingin’ with EBRPSS to announce the 2nd Fine Arts! Annual EBR Student The date is set. Mark your calendars now!!! Short Film Festival! May 2nd, 2021 from 1:00 to 4:00 pm. Visual Arts Teachers: Start collecting student work. Email Susan Arnold when Fine Arts teachers, please tell your students about this you have work ready to go. -

An Investigation of Dalcroze-Inspired Embodied Movement

AN INVESTIGATION OF DALCROZE-INSPIRED EMBODIED MOVEMENT WITHIN UNDERGRADUATE CONDUCTING COURSEWORK by NICHOLAS J. MARZUOLA Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Nathan B. Kruse Department of Music CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2019 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the dissertation of Nicholas J. Marzuola, candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy*. (signed) Dr. Nathan B. Kruse (chair of the committee) Dr. Lisa Huisman Koops Dr. Matthew L. Garrett Dr. Anthony Jack (date) March 25, 2019 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. 2 Copyright © 2019 by Nicholas J. Marzuola All rights reserved 3 DEDICATION To Allison, my loving wife and best friend. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................... 5 LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................... 10 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................. 11 ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................... 13 CHAPTER ONE, INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 15 History of Conducting .................................................................................................. -

“A Call to Colors” to the Various North Carolina Alumni Desreta Jackson, Applauded As Chapters Represented

PRESORTED STANDARD .S. POSTAGE PAID Healthy Living Feature: Heart Attack/Stroke WILMINGTON, N.C. PERMIT - NO. 675 50 CENTS Established 1987 VOLUME 33, NO. 7 2019 Theme: Great is the Company that Published It! Week of July 25 - July 31, 2019 NATIONWIDE VOTER MOBILIZATION IS OUR PRIORITY INSIDE THIS EDITION 4 5 Black 7 2.....................Editorials & Politics 369th Black Children Entrepreneurs 3...................... Health & Wellness Fed to Hogs 4....................Career & Education Experience Raise $8 Million Band Ties HBCU 5..... Business News & Resources & Alligators 6.......... Events & Announcements Musicians to WWI for Barbershop- 7.................................Spirit & Life Black History Focused App 1900’s 8..................................Classifieds NCCU ALUMNI NHRMC ON SUMMIT FOCUSES “A CALL TO A GDN ExclusivE: vol. ii COLORS” PArt xvi Wilmington, NC - a referral destination for is the only DNV-certified interventional coverage New Hanover Regional patients across southeastern Comprehensive Stroke Center to treat patients suffering Medical Center has North Carolina needing the in North Carolina cerebrovascular emergencies, received certification from most advanced care for strokes “Stroke care has evolved including stroke and DNV GL - Healthcare as a and aneurysms.” rapidly over the last few years aneurysms. Angela Lewis Richard Smith Samuel Cooper Comprehensive Stroke Center, The DNV GL - Healthcare and developing stroke “Comprehensive stroke reflecting the highest level of Comprehensive Stroke Center networks is imperative to certification at NHRMC By Cash Michaels, Contributing Writer competence for treatment of Certification is based on improve outcomes,” said demonstrates our commitment serious stroke events. standards set forth by the Brain Vinodh Doss, DO, Director of to our community to provide When the National Historically Black College and Alumni “Comprehensive stroke Attack Coalition and the Neurointerventional Surgery. -

American Mavericks Festival

VISIONARIES PIONEERS ICONOCLASTS A LOOK AT 20TH-CENTURY MUSIC IN THE UNITED STATES, FROM THE SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY EDITED BY SUSAN KEY AND LARRY ROTHE PUBLISHED IN COOPERATION WITH THE UNIVERSITY OF CaLIFORNIA PRESS The San Francisco Symphony TO PHYLLIS WAttIs— San Francisco, California FRIEND OF THE SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY, CHAMPION OF NEW AND UNUSUAL MUSIC, All inquiries about the sales and distribution of this volume should be directed to the University of California Press. BENEFACTOR OF THE AMERICAN MAVERICKS FESTIVAL, FREE SPIRIT, CATALYST, AND MUSE. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England ©2001 by The San Francisco Symphony ISBN 0-520-23304-2 (cloth) Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the Library of Congress. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI / NISO Z390.48-1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper). Printed in Canada Designed by i4 Design, Sausalito, California Back cover: Detail from score of Earle Brown’s Cross Sections and Color Fields. 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 v Contents vii From the Editors When Michael Tilson Thomas announced that he intended to devote three weeks in June 2000 to a survey of some of the 20th century’s most radical American composers, those of us associated with the San Francisco Symphony held our breaths. The Symphony has never apologized for its commitment to new music, but American orchestras have to deal with economic realities. For the San Francisco Symphony, as for its siblings across the country, the guiding principle of programming has always been balance. -

Open Drane Dissertation.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School AN ORAL HISTORY OF THE NAVY BAND B-1: THE FIRST ALL-BLACK NAVY BAND OF WORLD WAR II A Dissertation in Music Education by Gregory Abdul Drane © 2020 Gregory Abdul Drane Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2020 ii The dissertation of Gregory Abdul Drane was reviewed and approved* by the following: O. Richard Bundy, Jr. Professor of Music Education, Emeritus Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Robert Gardner Associate Professor of Music Education David McBride Professor of African American Studies and African American History Ann Clements Professor of Music Education Linda Thornton Professor of Music Education Chair of the Graduate Program iii ABSTRACT This study investigates the service of the Navy Band B-1, the first all-black Navy band to serve during World War II. For many years it was believed that the black musicians of the Great Lakes Camp held the distinction as the first all-black Navy band to serve during World War II. However, prior to the opening of the Navy’s Negro School of Music at the Great Lakes Camps, the Navy Band B-1 had already completed its training and was in full service. This study documents the historical timeline of events associated with the formation of the Navy Band B-1, the recruitment of the bandsmen, their service in the United States Navy, and their valuable contributions to the country. Surviving members of the Navy Band B-1 were interviewed to share their stories and reflections of their service during World War II. -

Queering Black Greek-Lettered Fraternities, Masculinity and Manhood : a Queer of Color Critique of Institutionality in Higher Education

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-2019 Queering black greek-lettered fraternities, masculinity and manhood : a queer of color critique of institutionality in higher education. Antron Demel Mahoney University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Africana Studies Commons, American Studies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, Higher Education Commons, History of Gender Commons, and the Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Mahoney, Antron Demel, "Queering black greek-lettered fraternities, masculinity and manhood : a queer of color critique of institutionality in higher education." (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3286. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/3286 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. QUEERING BLACK GREEK-LETTERED FRATERNITIES, MASCULINITY AND MANHOOD: A QUEER OF COLOR CRITIQUE OF INSTITUTIONALITY IN HIGHER EDUCATION By Antron Demel Mahoney B.S.,