Connoquenessing Plan Cover

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

County of Butler Comprehensive Plan

THE COUNTY OF BUTLER COMPREHENSIVE PLAN PHASE I (RECONNAISSANCE REPORT) 1997 Prepared by the Butler County Planning Commission The preparation of th~sreport was financed in part through a State Planning Assistance Grant (SPAG) from the Department of Community and Economic Development, under the: provisions of Act 5A, approved June 30, 1995, as administered by the Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development, Strategic Planning and Program Operations Office. p James L. Kennedy, Chairman William L. McCarrier Glenn L. Anderson PlanninP Commission Jeffrey M. Thompson, Chairman Howard L. Graham Paul M. Montgomery Theodore J. Walwik Howie J. Pentony Frank E. Uhl Kenneth M. Thomas James F. Peters Daniel D. Santoro Planning Director David P. Johnston TABLE OF CONTENTS m History and Historic Preservation ........................................... HHPl Native American Prehistory ............................................ HHPl Heritage of the Native American Period ................................... HHP2 The Early Historic Period: Pre-Settlement ................................... HHP3 Heritage of the Native-White and Colonial Conflicts in Butler County ............."P4 PlaceNarnes ..................................................... HHP4 DonatiodDepreciation Lands ........................................ HHP4 Initial Settlement of the County, 1790-1860 ................................ HHPS The Heritage of the Era of Settlement in Butler County ....................... HHP7 The Industrial Revolution - 1860-1945 ................................... -

05/24/2019 BUTLER COUNTY LEGAL JOURNAL Vol. 28 No

05/24/2019 BUTLER COUNTY LEGAL JOURNAL Vol. 28 No. 43 ESTATE NOTICES Estate of: Charles Louis Brochetti Notice is hereby given that in the estates of a/k/a: Charles L Brochetti the decedents set forth below the Register Late of: Slippery Rock PA of Wills has granted letters testamentary Executor: Ann E Sesti or of administration to the persons named. 150 Harrison Drive All persons having claims or demands Indiana PA 15701 against said estates are requested to make Attorney: Ronald W Coyer known the same, and all persons indebted SR Law LLC to said estates are requested to make 631 Kelly Blvd PO Box 67 payment without delay, to the executors Slippery Rock PA 16057 or administrators or their attorneys named below. Estate of: Joyce A Ciani _______ Late of: Buffalo Township PA Executor: Robin J Dickey FIRST PUBLICATION 300 Muddy Creek Drive Butler PA 16001 Estate of: Maria Abraham Executor: Robert L Ciani II Late of: Seven Fields PA 214 Cole Road Executor: Sylvia Herdt Sarver PA 16055 225 Adams Pointe Blvd Attorney: Laurel Hartshorn Esq Unit 9 PO Box 553 Mars PA 16046 Saxonburg PA 16056 Attorney: Nora C Peace 1501 Mount Royal Blvd Estate of: Virginia L Craska Glenshaw PA 15116 Late of: Mars PA Executor: Francis M Craska Jr Estate of: Erma Lee Bailie 9023 Audubon Drive a/k/a: Erma L Bailie Gibsonia PA 15044 Late of: Butler Township PA Attorney: Dawn A Botsford Executor: Anne Conn 373 Republic Street 237 Meadowbrook Drive Pittsburgh PA 15211 Cranberry Township PA 16066 Attorney: Michael J Pater Estate of: Doris Mae Hartman 101 East Diamond Street -

Lower Connoquenessing Stormwater Planning Study

LOWER CONNOQUENESSING STORMWATER PLANNING STUDY Submitted to: Submitted by: BUTLER COUNTY HERBERT, ROWLAND & GRUBIC, INC. ATTN: Mr. Mark Gordon 200 West Kensinger Drive, Suite 400 Butler County Government Center Cranberry Township, PA 16066 124 West Diamond Street 724.779.4777 Butler, PA 16003 Date: March 10, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS PROJECT OVERVIEW ................................................................................................................ 1 RATE CONTROLS ....................................................................................................................... 2 PROBLEM AREAS .................................................................................................................... 10 ADAMS TOWNSHIP ................................................................................................................. 12 BUTLER COUNTY ...................................................................................................................... 16 CRANBERRY TOWNSHIP ......................................................................................................... 18 EVANS CITY BOROUGH .......................................................................................................... 22 FORWARD TOWNSHIP ............................................................................................................ 25 HARMONY BOROUGH ........................................................................................................... 28 JACKSON TOWNSHIP ............................................................................................................ -

LITTLE CONNOQUENESSING CREEK WATERSHED TMDL Butler County

DRAFT LITTLE CONNOQUENESSING CREEK WATERSHED TMDL Butler County For Acid Mine Drainage Affected Segments Prepared by: Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection September 30, 2008 1 DRAFT TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction................................................................................................................................. 3 Directions to the Little Connoquenessing Creek Watershed...................................................... 7 Segments addressed in this TMDL............................................................................................. 7 Clean Water Act Requirements .................................................................................................. 8 Section 303(d) Listing Process ................................................................................................... 9 Basic Steps for Determining a TMDL...................................................................................... 10 Watershed Background............................................................................................................. 10 AMD Methodology................................................................................................................... 12 TMDL Endpoints...................................................................................................................... 14 TMDL Elements (WLA, LA, MOS) ........................................................................................ 15 Allocation Summary................................................................................................................ -

Butler County Natural Heritage Inventory, 1991

BUTLER COUNTY NATURAL HERITAGE INVENTORY Lisa L. Smith, Natural Heritage Ecologist Charles W. Bier, Associate Director, Natural Science and Stewardship Department Paul G. Wiegman, Director, Natural Science and Stewardship Department Chris J. Boget, Data Manager Bernice K. Beck, Data Handler Western Pennsylvania Conservancy 316 Fourth Avenue Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15222 July 1991 BUTLER COUNTY NATURAL HERITAGE INVENTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION 4 COUNTY OVERVIEW 9 PENNSYLVANIA NATURAL DIVERSITY INVENTORY 14 NATURAL HERITAGE INVENTORY METHODS 15 RESULTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 17 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 133 LITERATURE CITED 134 APPENDICES I. Federal and State Endangered Species Categories, Global and State Element Ranks 135 II. County Significance Ranks 141 III. Potential Natural Heritage Inventory Form 142 IV. Recommended Natural Heritage Field Survey Form 143 V. Classification of Natural Communities in Pennsylvania (Draft) 144 LIST OF TABLES PAGE 1. Summary of sites in order of relative county significance 20 2. Important managed areas protecting biotic resources in Butler County 24 3. Butler County municipality summaries 27 Tables summarizing USGS quadrangles Baden 116 Barkeyville 37 Butler 103 Chicora 93 Curtisville 125 East Butler 90 Eau Claire 41 Emlenton 44 Evans City 108 Freeport 128 Grove City 34 Harlansburg 75 Hilliards 51 Mars 119 Mount Chestnut 86 Parker 48 Portersville 77 Prospect 81 Saxonburg 100 Slippery Rock 63 Valencia 122 West Sunbury 57 Worthington 97 Zelienople 113 LIST OF FIGURES PAGE 1. USGS quadrangle map index of Butler County 25 2. Municipalities of Butler County 26 3 INTRODUCTION Butler County possesses a wealth of natural resources including its flora, fauna, and natural habitats such as forests, wetlands, and streams. -

BUTLER COUNTY, PA Museums, Historical Societies & Historic Sites

BUTLER COUNTY, PA Museums, Historical Societies & Historic Sites Table of Contents Dig into the past in Butler County, Pa. *Numbers in parenthesis correspond to maps Dig into the past in Butler County, Pa. ..................................................... 3 Our small towns are packed with some big his- Butler tory! Did you know that the first U.S. President, Butler County Historical Society (1) .................................................. 4 George Washington, set foot here? Or that Maridon Museum (2) .............................................................................. 6 Butler is the birthplace of the “jeep?” Learn Downtown Butler Map .......................................................................... 7 about these and much more through Harmony, Zelienople & Evans City our museums and historic sites. Harmony National Historic Landmark District (3) ........................ 8 And it won’t boring! Experience Zelienople Historical Society (4).......................................................10 history first-hand through Lancaster Township History Center (5) ..........................................10 historic reenactments and Evans City Area Historical Society (6) .............................................11 encampments. Discover what Providence Plantation (7) ...................................................................11 class was like in a one room Washington’s Trail, Prospect & Slippery Rock schoolhouse. Celebrate Washington’s Trail (8) ..........................................................................12 -

Southwestern Pennsylvania Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System (MS4) Permittees

Southwestern Pennsylvania Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System (MS4) Permittees ALLEGHENY COUNTY Municipality Stormwater Watershed(s) River Watershed(s) Aleppo Twp. Ohio River Ohio River Avalon Borough Ohio River Ohio River Baldwin Borough Monongahela River Monongahela River Peters Creek Monongahela River Sawmill Run Ohio River Baldwin Township Sawmill Run Ohio River Bellevue Borough Ohio River Ohio River Ben Avon Borough Big Sewickley Creek Ohio River Little Sewickley Creek Ohio River Bethel Park Borough Peters Creek Monongahela River Chartiers Creek Ohio River Sawmill Run Ohio River Blawnox Borough Allegheny River Allegheny River Brackenridge Borough Allegheny River Allegheny River Bull Creek Allegheny River Braddock Hills Borough Monongahela River Monongahela River Turtle Creek Monongahela River Bradford Woods Pine Run Allegheny River Borough Connoquenessing Creek Beaver River Big Sewickley Creek Ohio River Brentwood Borough Monongahela River Monongahela River Sawmill Run Ohio River Bridgeville Borough Chartiers Creek Ohio River Carnegie Borough Chartiers Creek Ohio River Castle Shannon Chartiers Creek Ohio River Borough Sawmill Run Ohio River ALLEGHENY COUNTY Municipality Stormwater Watershed(s) River Watershed(s) Cheswick Borough Allegheny River Allegheny River Churchill Borough Turtle Creek Monongahela River Clairton City Monongahela River Monongahela River Peters Creek Monongahela River Collier Township Chartiers Creek Ohio River Robinson Run Ohio River Coraopolis Borough Montour Run Ohio River Ohio River Ohio River Crescent Township -

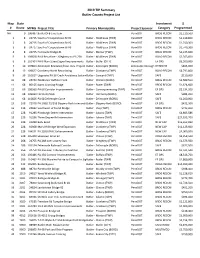

2019 TIP Summary Butler County Project List

2019 TIP Summary Butler County Project List Map State Investment $ # Route MPMS Project Title Primary Municipality Project Sponsor Category Programmed NA 0 106487 Butler DFB Line Item PennDOT BRDG RECON $1,210,500 1 8 24715 South of Cooperstown Br #1 Butler ‐ Middlesex (TWP) PennDOT BRDG RECON $2,219,800 2 8 24716 South of Cooperstown Br #2 Butler ‐ Middlesex (TWP) PennDOT BRDG RECON $1,740,300 3 8 24717 South of Cooperstown Br #3 Butler ‐ Middlesex (TWP) PennDOT BRDG RECON $1,740,300 4 8 24725 Harrisville Bridge #1 Butler ‐ Mercer (TWP) PennDOT BRDG RECON $2,225,600 5 8 109628 PA 8 Resurface ‐ Allegheny to PA 228 Butler ‐ Middlesex (TWP) PennDOT ROAD RECON $2,363,600 6 8 110464 PA 8 Main Street Signal Improvements Butler ‐ Butler (CITY) PennDOT EF OPS $3,500,000 7 19 107823 Zelienople Revitalize/Econ. Dev. Project Butler ‐ Zelienople (BORO) Zelienople Borough OTHER TE $465,000 8 19 109627 Cranberry North Resurfacing Butler ‐ Cranberry (TWP) PennDOT ROAD RECON $6,792,800 9 38 110827 Upgrades PA 38 Crash Avoidance SystemButler ‐ Concord (TWP) PennDOT SAFE $110,000 10 68 24740 PA 68 over Buffalo Creek Butler ‐ Chicora (BORO) PennDOT BRDG RECON $3,589,500 11 68 86105 Karns Crossing Bridge Butler ‐ Butler (TWP) PennDOT BRDG RECON $1,624,600 12 68 106568 PA 68 Corridor Improvements Butler ‐ Connoquenessing (TWP) PennDOT EF OPS $2,134,200 13 68 109690 Harmony Slide Butler ‐ Harmony (BORO) PennDOT SAFE $284,200 14 68 110826 PA 68 Zelienople Curve Butler ‐ Zelienople (BORO) PennDOT SAFE $1,200,000 15 108 72378 PA 108/173/258 Slippery Rock Intersecti -

2016 Outreach Butler County.Pdf

Outreach 2016 Agenda • Budget in Brief • Liquid Fuels Distributions • 2016 Construction Projects • 2017-2019 Projects in Design • County Budgets • County Transformation • P3 – Public/Private Partnership for Bridges - update • County Maintenance Overview Total Operating Budget 2016-17 Budget Overview $7.84 Billion PennDOT’s Total Budget Motor License Fund 2016-17 Exhibit 1-1 PennDOT Present Funding Forecast 2,000,000 Total Highway & Bridge Programs Funded by the Motor License Fund 1,800,000 1,600,000 1,400,000 Maintenance State Police 1,200,000 Construction Total Construction (Non Restricted) 1,000,000 $ In Thousands 800,000 Construction (Restricted/Dedicated) 600,000 400,000 Act 89 Maintenance Supplement 200,000 - *07-08 Act *13-14 Act New 12 Year Program FY 17-28 44 of 2007 89 of 2013 PennDOT Present Funding Forecast Assuming $300 Million Cap on the State Police in the MLF Total Highway & Bridge Programs Funded by the Motor License Fund 2,500,000 2,000,000 Construction Total Construction (Non Restricted) 1,500,000 Maintenance Grown at 1.5% $ Thousands In 1,000,000 Construction (Restricted/Dedicated) 500,000 Act 89 Maintenance Supplement State Police - PennDOT Present Funding Forecast Assuming $500 Million Cap on the State Police in the MLF Total Highway & Bridge Programs Funded by the Motor License Fund 2,000,000 1,800,000 Construction Total 1,600,000 1,400,000 Maintenance Grown at 1.25% 1,200,000 Construction (Non Restricted) 1,000,000 $ Thousands In Construction (Restricted/Dedicated) 800,000 600,000 State Police 400,000 Act 89 Maintenance -

2021-02-02 010515__2021 Stocking Schedule All.Pdf

Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission 2021 Trout Stocking Schedule (as of 2/1/2021, visit fishandboat.com/stocking for changes) County Water Sec Stocking Date BRK BRO RB GD Meeting Place Mtg Time Upper Limit Lower Limit Adams Bermudian Creek 2 4/6/2021 X X Fairfield PO - SR 116 10:00 CRANBERRY ROAD BRIDGE (SR1014) Wierman's Mill Road Bridge (SR 1009) Adams Bermudian Creek 2 3/15/2021 X X X York Springs Fire Company Community Center 10:00 CRANBERRY ROAD BRIDGE (SR1014) Wierman's Mill Road Bridge (SR 1009) Adams Bermudian Creek 4 3/15/2021 X X York Springs Fire Company Community Center 10:00 GREENBRIAR ROAD BRIDGE (T-619) SR 94 BRIDGE (SR0094) Adams Conewago Creek 3 4/22/2021 X X Adams Co. National Bank-Arendtsville 10:00 SR0234 BRDG AT ARENDTSVILLE 200 M DNS RUSSELL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) Adams Conewago Creek 3 2/27/2021 X X X Adams Co. National Bank-Arendtsville 10:00 SR0234 BRDG AT ARENDTSVILLE 200 M DNS RUSSELL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) Adams Conewago Creek 4 4/22/2021 X X X Adams Co. National Bank-Arendtsville 10:00 200 M DNS RUSSEL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) RT 34 BRDG (SR0034) Adams Conewago Creek 4 10/6/2021 X X Letterkenny Reservoir 10:00 200 M DNS RUSSEL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) RT 34 BRDG (SR0034) Adams Conewago Creek 4 2/27/2021 X X X Adams Co. National Bank-Arendtsville 10:00 200 M DNS RUSSEL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) RT 34 BRDG (SR0034) Adams Conewago Creek 5 4/22/2021 X X Adams Co. -

Slippery Rock Creek Watershed Conservation Plan June 2011

SlipperySlippery RockRock CreekCreek WatershedWatershed ConservationConservation PlanPlan JuneJune 20112011 Slippery Rock Watershed Coalition 434 Spring Street Ext., Mars, PA 16046 www.srwc.org Major funders: Community Conservation Partnerships Program Keystone Recreation, Park & Conservation Fund Administered by: PA Dept. of Conservation and Natural Resources Bureau of Recreation and Conservation Foundation for Pennsylvania Watersheds Photo by: Tom Grote The Pennsylvania Rivers Conservation Program Slippery Rock Creek Watershed Conservation Plan June 2011 Funding Provided in Part By: Community Conservation Partnerships Program Keystone Recreation, Park and Conservation Fund Administered by: Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Bureau of Recreation and Conservation Location Slippery Rock Creek Watershed Ohio River Basin Beaver, Butler, Lawrence, Mercer, Venango Counties Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Project Sponsor: Prepared for: Stream Restoration Incorporated A PA Non-Profit Organization 501(c)(3) 434 Spring Street Extension Slippery Rock Watershed Coalition Mars, PA 16046 434 Spring Street Extension www.streamrestorationinc.org Mars, PA 16046 www.srwc.org Plan Prepared by: Laurie Popeck & Tom Grote, Proj. Facilitators Josh McGinnis, Sustainable Systems Analyst Shaun L. Busler, GISP Melissa Brewer, Planner Wil Taylor, Mgr., Jennings Env. Ed. Ctr. Bryan J. Page, Env. Chemist Timothy P. Danehy, QEP Margaret H. Dunn, PG Slippery Rock Creek Watershed Conservation Plan June 2011 Beaver, Butler, Lawrence, Mercer, Venango Counties, PA Ohio River Basin ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Our gratitude is extended to every individual, organization, and agency that contributed to the success of the Slippery Rock Creek Watershed Conservation Plan. We are very thankful for the time and effort devoted to this worthwhile project. Advisory Council Name Organization Doniele Andrus Friends of McConnells Mills State Park Bob Beran Beran Environmental Inc. -

Beaver County, Pennsylvania (All Jurisdictions)

VOLUME 1 OF 3 BEAVER COUNTY, Beaver County PENNSYLVANIA (ALL JURISDICTIONS) COMMUNITY NAME COMMUNITY NUMBER COMMUNITY NAME COMMUNITY NUMBER ALIQUIPPA, CITY OF 420101 HOMEWOOD, BOROUGH OF 422318 AMBRIDGE, BOROUGH OF 420102 HOOKSTOWN, BOROUGH OF 422319 BADEN, BOROUGH OF 420103 HOPEWELL, TOWNSHIP OF 421321 BEAVER, BOROUGH OF 420104 INDEPENDENCE, TOWNSHIP OF 421323 BEAVER FALLS, CITY OF 420105 INDUSTRY, BOROUGH OF 420113 BIG BEAVER, BOROUGH OF 422307 KOPPEL, BOROUGH OF 422320 BRIDGEWATER, BOROUGH OF 420106 MARION, TOWNSHIP OF 422249 BRIGHTON, TOWNSHIP OF 422309 MIDLAND, BOROUGH OF 422321 CENTER, TOWNSHIP OF 422310 MONACA, BOROUGH OF 420114 CHIPPEWA, TOWNSHIP OF 422311 NEW BRIGHTON, BOROUGH OF 420115 CONWAY, BOROUGH OF 420107 NEW GALILEE, BOROUGH OF 422322 DARLINGTON, BOROUGH OF 421319 NEW SEWICKLEY, TOWNSHIP OF 422323 DARLINGTON, TOWNSHIP OF 422312 NORTH SEWICKLEY, TOWNSHIP OF 421161 DAUGHERTY, TOWNSHIP OF 422313 OHIOVILLE, BOROUGH OF 422324 EAST ROCHESTER, BOROUGH OF 420108 PATTERSON, TOWNSHIP OF 422326 EASTVALE, BOROUGH OF 422314 PATTERSON HEIGHTS, BOROUGH OF 422325 ECONOMY, BOROUGH OF 420109 POTTER, TOWNSHIP OF 422327 FALLSTON, BOROUGH OF 420110 PULASKI, TOWNSHIP OF 422328 FRANKFORT SPRINGS, BOROUGH OF 422315 RACCOON, TOWNSHIP OF 421220 FRANKLIN, TOWNSHIP OF 421065 ROCHESTER, BOROUGH OF 420116 FREEDOM, BOROUGH OF 420111 ROCHESTER, TOWNSHIP OF 421322 GEORGETOWN, BOROUGH OF 422316 SHIPPINGPORT, BOROUGH OF 420117 GLASGOW, BOROUGH OF 420112 SOUTH BEAVER, TOWNSHIP OF 422329 GREENE, TOWNSHIP OF 422317 SOUTH HEIGHTS, BOROUGH OF 422330 HANOVER, TOWNSHIP OF 421223 VANPORT, TOWNSHIP OF 421320 HARMONY, TOWNSHIP OF 421038 WEST MAYFIELD, BOROUGH OF 422331 WHITE, TOWNSHIP OF 420057 FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 42007CV001A NOTICE TO FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY USERS Communities participating in the National Flood Insurance Program have established repositories of flood hazard data for floodplain management and flood insurance purposes.