The Spoken Text CD 1 1 a Door Creaks; Wind, Thunder, and Woman's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 53,1933

SANDERS THEATRE . CAMBRIDGE HARVARD UNIVERSITY Thursday Evening, December 7, at 8.00 a* '%% '« BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. FIFTY-THIRD SEASON J933-J934 prsgiwvae SANDERS THEATRE CAMBRIDGE HARVARD UNIVERSITY FIFTY-THIRD SEASON, 1933-1934 INC. Dr. SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor SEASON 1933-1934 THURSDAY EVENING, DECEMBER 7, at 8.00 WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE COPYRIGHT, 1933, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, INC. THE OFFICERS AND TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. BENTLEY W. WARREN President HENRY B. SAWYER Vice-President ERNEST B. DANE Treasurer ALLSTON BURR ROGER I. LEE HENRY B. CABOT WILLIAM PHILLIPS ERNEST B. DANE EDWARD M. PICKMAN N. PENROSE HALLOWELL HENRY B. SAWYER M. A. DE WOLFE HOWE BENTLEY W. WARREN Manager W. H. BRENNAN, Manager G. E. IUDD, Assistant l Cljanbler & Co. Famous for Style and Quality for Over a Century From our Underwear Section — Sixth Floor come these lovely Qift Suggestions! Silk or Satin Gowns, Pajamas, Slips, dance sets, chemises, panties 2 25 Dance sets with up- lift lace brassieres. Satin panties, fine silk crepe slips, tailored, embroidered or lace trimmed. 3 00 Satin sheath slips, crepe evening slips, satin dance sets, panties and chemises, simply or elabor- ately lace trimmed. Empire, Princess and Sheath Gowns of lovely crepe. 3 95 Two-piece pajamas with puff sleeves, ex- quisitely hand-made gowns, satin gowns with imported laces, satin slips, lace trimmed or tailored, for daytime and evening. SANDERS THEATRE . CAMBRIDGE HARVARD UNIVERSITY Fifty-third Season, 1933—1934 Dr. SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor THIRD CONCERT THURSDAY EVENING, DECEMBER 7 AT 8.00 PROGRAMME Mozart "Eine Kleine Nachtmusik," Serenade for String Orchestra (Koechel No. -

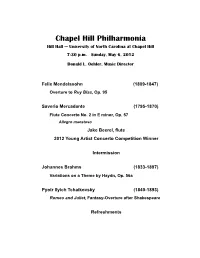

Concert Program

Chapel Hill Philharmonia Hill Hall — University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 7:30 p.m. Sunday, May 6, 2012 Donald L. Oehler, Music Director Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) Overture to Ruy Blas, Op. 95 Saverio Mercadante (1795-1870) Flute Concerto No. 2 in E minor, Op. 57 Allegro maestoso Jake Beerel, flute 2012 Young Artist Concerto Competition Winner Intermission Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Variations on a Theme by Haydn, Op. 56a Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) Romeo and Juliet, Fantasy-Overture after Shakespeare Refreshments Inspirations William Shakespeare conveyed the overwhelming impact of Julius Caesar in imperial Rome: “Why, man, he doth bestride the narrow world like a Colussus.” So might 19th century composers have viewed the figure of Ludwig van Beethoven. With his Symphony No. 3, known as Eroica, composed in 1803, Beethoven radically altered the evolution of symphonic music. The work was inspired by Napoléon Bonaparte’s republican ideals while rejecting that ‘hero’s’ assumption of an imperial mantle. Beethoven broke precedent by employing his art “as a vehicle to convey beliefs,” expanding beyond compositional technique to add the “dimension of meaning and interpretation. All the more remarkable…the high priest of absolute music, effected this change.” (composer W.A. DeWitt) Beethoven, in a word, brought Romanticism to the concert hall, “replac[ing] the Enlightenment cult of reason with a cult of instinct, passion, and the creative genius as virtual demigod. The Romantics seized upon Beethoven’s emotionalism, his sense of the individual as hero.” (composer/writer Jan Swafford) The expression of this new sensibility took many forms, ranging from intensified expression within classical forms, exemplified by Felix Mendelssohn or Johannes Brahms, to the unbridled fervor of Piyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, the revolutionary virtuosity and structural innovations of Franz Liszt, the hallucinatory visions of Hector Berlioz, and the megalomania of Richard Wagner. -

Monday, June 30Th at 7:30 P.M. Blue Lake Fine Arts Camp Free Admission

JUNE 2008 Listener BLUE LAKE PUBLIC RADIO PROGRAM GUIDE Monday, June 30th at 7:30 p.m. TheBlue Grand Lake Rapids Fine ArtsSymphony’s Camp DavidFree LockingtonAdmission WBLV-FM 90.3 - MUSKEGON & THE LAKESHORE WBLU-FM 88.9 - GRAND RAPIDS A Service of Blue Lake Fine Arts Camp 231-894-5656 http://www.bluelake.org J U N E 2 0 0 8 H i g h l i g h t s “Listener” Volume XXVI, No.6 “Listener” is published monthly by Blue Lake Public Radio, Route Two, Twin Lake, MI 49457. (231)894-5656. Summer at Blue Lake WBLV, FM-90.3, and WBLU, FM-88.9, are owned and Summer is here and with it a terrific live from operated by Blue Lake Fine Arts Camp Blue Lake and broadcast from the Rosenberg- season of performances at Blue Lake Fine Clark Broadcast Center on Blue Lake’s Arts Camp. Highlighting this summer’s Muskegon County Campus. WBLV and WBLU are public, non-commercial concerts is a presentation of Beethoven’s stations. Symphony No. 9, the Choral Symphony, Blue Lake Fine Arts Camp with the Blue Lake Festival Orchestra, admits students of any race, color, Festival Choir, Domkantorei St. Martin from national or ethnic origin and does not discriminate in the administration of its Mainz, Germany, and soloists, conducted programs. by Professor Mathias Breitschaft. The U.S. BLUE LAKE FINE ARTS CAMP Army Field Band and Soldier’s Chorus BOARD OF TRUSTEES will present a free concert on June 30th, and Jefferson Baum, Grand Haven A series of five live jazz performances John Cooper, E. -

Projet3 Mise En Page 2

DIMANCHE 17 JANVIER 2016 20H MAISON DE LA RADIO - AUDITORIUM ORCHESTRE NATIONAL DE FRANCE DANIELE GATTI DIRECTEUR MUSICAL JAMES CONLON DIRECTION ELISABETH GLAB VIOLON SOLO PROGRAMME Johannes Brahms Ouverture pour une fête académique en do mineur, opus 80 (10 minutes environ) Antonín Dvořák Trois danses slaves opus72 n° 1 en si majeur n° 2 en mi mineur n° 7 en ut majeur (16 minutes environ) Symphonie n° 8 en sol majeur, op. 88 1. Allegro con brio 2. Adagio 3. Allegretto grazioso 4. Allegro ma non troppo (40 minutes environ) Fin de concert prévue à 22h environ › Ce concert sera diffusé le jeudi 11 février à 20h sur France Musique. Il est également disponible à l’écoute sur francemusique.fr › Retrouvez la page facebook des concerts de Radio France et de l’«Orchestre National de France». › Consultez le site sur maisondelaradio.fr rubrique concerts. JOHANNES BRAHMS 1833-1897 OUVERTURE POUR UNE FÊTE ACADÉMIQUE (AKADEMISCHE FESTOUVERTÜRE) EN DO MINEUR OPUS 80 COMPOSÉE À VIENNE EN 1879 / CRÉÉE LE 4 JANVIER 1881 À BRESLAU / DÉDIÉE À L'UNIVERSITÉ DE BRESLAU Brahms n'est pas pour rien fils d'un grand port, et l'on verra ce qu'il a voulu saisir de mélodies errantes, venues de tous les horizons. Marcel Beaufils En 1879, Breslau était la sixième ville d'Allemagne avec 270 000 habitants et son université s'enorgueillissait d'enseignants tels que le biologiste Ferdinand Cohn, l'un des fondateurs de la bactériologie moderne, le physicien Gustav Kirchhoff, dont les lois du même nom font encore autorité dans le domaine de l'énergie électrique, ou encore le poète August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben, auteur du Lied der Deutschen (Deutschland Deutschland über alles…). -

Papéis Normativos E Práticas Sociais

Agnes Ayres (1898-194): Rodolfo Valentino e Agnes Ayres em “The Sheik” (1921) The Donovan Affair (1929) The Affairs of Anatol (1921) The Rubaiyat of a Scotch Highball Broken Hearted (1929) Cappy Ricks (1921) (1918) Bye, Bye, Buddy (1929) Too Much Speed (1921) Their Godson (1918) Into the Night (1928) The Love Special (1921) Sweets of the Sour (1918) The Lady of Victories (1928) Forbidden Fruit (1921) Coals for the Fire (1918) Eve's Love Letters (1927) The Furnace (1920) Their Anniversary Feast (1918) The Son of the Sheik (1926) Held by the Enemy (1920) A Four Cornered Triangle (1918) Morals for Men (1925) Go and Get It (1920) Seeking an Oversoul (1918) The Awful Truth (1925) The Inner Voice (1920) A Little Ouija Work (1918) Her Market Value (1925) A Modern Salome (1920) The Purple Dress (1918) Tomorrow's Love (1925) The Ghost of a Chance (1919) His Wife's Hero (1917) Worldly Goods (1924) Sacred Silence (1919) His Wife Got All the Credit (1917) The Story Without a Name (1924) The Gamblers (1919) He Had to Camouflage (1917) Detained (1924) In Honor's Web (1919) Paging Page Two (1917) The Guilty One (1924) The Buried Treasure (1919) A Family Flivver (1917) Bluff (1924) The Guardian of the Accolade (1919) The Renaissance at Charleroi (1917) When a Girl Loves (1924) A Stitch in Time (1919) The Bottom of the Well (1917) Don't Call It Love (1923) Shocks of Doom (1919) The Furnished Room (1917) The Ten Commandments (1923) The Girl Problem (1919) The Defeat of the City (1917) The Marriage Maker (1923) Transients in Arcadia (1918) Richard the Brazen (1917) Racing Hearts (1923) A Bird of Bagdad (1918) The Dazzling Miss Davison (1917) The Heart Raider (1923) Springtime à la Carte (1918) The Mirror (1917) A Daughter of Luxury (1922) Mammon and the Archer (1918) Hedda Gabler (1917) Clarence (1922) One Thousand Dollars (1918) The Debt (1917) Borderland (1922) The Girl and the Graft (1918) Mrs. -

Opis Programa Diplomskog Ispita Diplomski Rad

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Zagreb Repository SVEUČILIŠTE U ZAGREBU MUZIČKA AKADEMIJA VI. ODSJEK IVANA ČULJAK OPIS PROGRAMA DIPLOMSKOG ISPITA DIPLOMSKI RAD ZAGREB, 2018. SVEUČILIŠTE U ZAGREBU MUZIČKA AKADEMIJA VI. ODSJEK OPIS PROGRAMA DIPLOMSKOG ISPITA DIPLOMSKI RAD Mentor: nasl. doc. art. Martin Draušnik Student: Ivana Čuljak Odsjek: VI. odsjek Smjer: Violina Ak. god. 2017/2018 ZAGREB, 2018. DIPLOMSKI RAD ODOBRIO MENTOR nasl. doc. art. Martin Draušnik _________________________ (potpis) U Zagrebu, _________________________ Diplomski rad obranjen________________ Ocjena ____________________________ POVJERENSTVO: 1.__________________________ 2.__________________________ 3._________________________ 4._________________________ 5._________________________ OPASKA: PAPIRNATA KOPIJA RADA DOSTAVLJENA JE ZA POHRANU KNJIŽNICI MUZIČKE AKADEMIJE SAŽETAK Ovaj rad bavi se opisom programa mog diplomskog koncerta. Rad je podijeljen na više poglavlja u kojima ću sažeto obraditi karakteristike skladatelja, te opis skladbi koje ću izvoditi na diplomskom ispitu u obliku opširne programske knjižice. Ključne riječi: diplomski rad, programska knjižica, violina ABSTRACT This paper deals with the description of my graduate concert. The paper is divided in chapters in wich I will give insight into composers characteristics and description of the pieces I will preform in my graduate concert, all written in form of lenghtly program notes. Key words: thesis, program notes, violin SADRŽAJ 1. Uvod 1 2. J. S. Bach; druga partita za solo violinu u d-molu, BWV 1004 2 2.1. Chaconne 3 3. W. A. Mozart 5 3.1. Koncert za violinu i orkestar u G-duru, br.3, K.216; Adagio, Rondeau 6 4. J. Brahms 7 4.1. Sonata za violinu i klavir u d-molu, br.3, op.108 8 5. -

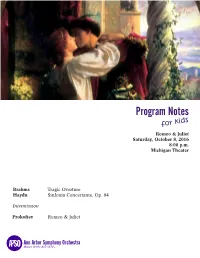

Program Notes

Program Notes for kids Romeo & Juliet Saturday, October 8, 2016 8:00 p.m. Michigan Theater Brahms Tragic Overture Haydn Sinfonia Concertante, Op. 84 Intermission Prokofiev Romeo & Juliet Tragic Overture by Johannes Brahms What kind of piece is this? This piece is a concert overture, similar to the overture of an opera. An opera overture is the opening instrumental movement that signals to the audience that the perfor- mance is about to begin. Similarily, a concert overture is a short and lively introduction to an instrumental con- cert. When was it written? Brahms wrote this piece in the summer of 1880 while on vacation. Brahms at the Piano What is it about? Brahms was a quiet and sad person, and really wanted to compose a piece about a tragedy. With no particular tragedy in mind, he created this overture as a contrast to his much happier Academic Festival Overture, which he completed in the same summer. When describing the two overtures to a friend, Brahms said “One of them weeps, the other laughs.” About the Composer Fun Facts Johannes Brahms | Born May 7, 1833 in Hamburg, Ger- Brahms never really grew up. He didn’t many | Died April 3, 1897 in Vienna, Austria care much about how he looked, he left his clothes lying all over the floor Family & Carfeer of his house, he loved merry-go-rounds and circus sideshows, and he continued Brahms’ father, Johann Jakob Brahms, was a bierfiedler: playing with his childhood toys until he literally, a “beer fiddler” who played in small bands at was almost 30 years old. -

Fest Für Clara Zum 200

FEST FÜR CLARA zum 200. Geburtstag von Clara Schumann FEST FÜR CLARA zum 200. Geburtstag von Clara Schumann Medaillon Clara um 1827 © Robert-Schumann-Haus Zwickau GRUSSWORT 7 Vorwort 8 AusstELLUNg 10 . KONZErtE 1 11 UND 2 11 2019 11 I wuNDERKIND UND JugENDtagEBÜchEr 20 II wartEN auF CLara – muttER voN acht KINDERN 27 III CLara IN BERLIN 34 IV LEBENSLANGE FREUNDschaFTEN UND WEGBEGLEITEr 40 V DOPPELGÄNGERKONZErt MIT schwÄRMBRIEFEN 45 IMPRESSUM VI hotEL DE russIe – UNTER DEN LINDEN 53 FESTSCHRIFT Fest für Clara KONTAKT [email protected] vII DIE OraNGE UND MYrthE HIER 59 HERAUSGEBERIN Hochschule für Musik Hanns Eisler Berlin, umSCHLAG Clara Schumann Gemälde (Adolph von Menzel, 1854) die Rektorin, Sarah Wedl-Wilson © Robert-Schumann-Haus Zwickau QUELLEN 70 TEXT Claar ter Horst, Theresa Schlegel (Kapitel III) AUFLAGE 1.000 REDAKTIONELLE miTARBEIT Sophia Schupelius DRUCK Onlineprinters GmbH KORREKTORAT Marit Magister, Ulrike Japes, DaNKsaguNG 72 Sophia Schupelius, Ulrike Schrader REDAKTIONSSCHLUSS 13. September 2019 Programm- und Besetzungsänderungen vorbehalten. REDAKTION Alexander Piefke, Marit Magister, Louise Hoffmeister, Ulrike Schrader WWW.HFM-BERLin.DE GRUSSWORT Sehr geehrte Damen und Herren, liebe Gäste, zum 200. Geburtstag von Clara Schumann ehrt die Hochschule für Musik Hanns Eisler Berlin die Komponistin, Pianistin, Musikmanagerin, Mutter und Ehefrau von Robert Schumann in einem außerordentlichen, zweitägigen „Fest für Clara“. Erst seit den 1980er Jahren hat sich die musikwissenschaftliche Forschung mit dieser Künstlerinnenbiografie auseinandergesetzt und dabei eine beeindruckend vielseitige und energische Frau für sich entdeckt. So wurde Clara Schumann von ihrem Vater zur Pianis- tin ausgebildet, als berühmteste Virtuosin ihrer Zeit ernährte sie lebenslang die Familie, sie komponierte bis zum Tode ihres Mannes Klavierwerke, Lieder, Kammermusik sowie ein Klavierkonzert und wurde als Herausgeberin der Werke Robert Schumanns zur strengsten Instanz um seinen Nachlass. -

Houlton Times, November 6, 1918

AROOSTOOK TIMES SHIRE TOWN OF April 13, 1860 AROOSTOOK COUNT) To HOULTON TIMES December 27, 1916 Carf Llbrerf HOULTON, MAINE, WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 6, 1918 No. 45 VOL. L V III DEMOBILIZATION WILL SOLICITOUS REGARDING HEALTH CONDITIONS ™ ES C0NFS J ? ruling | AROOSTOOK WHEAT REQUIRE TWO YEARS LETTERS FROM HEALTH OF EASTERN With this issue of the TIMES, thej AFTER PEACE a MAINE CITIZENS? Times Publishing Co. has conformed j CROP MOST Demobilization of the American The non-reeejpi Of certain packages IN HOULTON to the Ruling of the War Priorities forces in France' will require' a period orderi'd by residents of Eastern .Maine SALVATION ARMY GIRLS FOLLOW Hoard of the U. S. Government, nut of two yi ars after peace is declared, has been accounted for. and further SATISFACTORY YANKEES TO FRONT IMPROVED ting down its list by removing tree according to a statement made by Gen, detail was given in Saturday's i-stm copies to exchanges, and others, as T. Coleman Dupont, who has just re McAllister Sisters Brave German of a Hangor paper, together with a well as running tin' minimum (plan turned from a two months visit to the Finest Quality and a Good Shells to Aid Grateful Ameri list of those to whom packages were Worst of the Epidemic Now tity to furnish our subscribers, also western front. can Fighters addressed. this week all subscribers who are more Yield Declaring that his views were tin* 1 he refere-m e above- referred to is Over than three months in arrears, will not refection of oflicial opinion among I’mbaldv no two other American a follow-;: -

Re-Dating the Premiere of Brahms's String Sextet in G, Op. 36

Volume XXXV, Number 2 Fall 2017 Re-dating the Premiere of Brahms’s String Sextet in G, Op. 36 In the record of first performances of Brahms’s music, two entries have always attracted attention, not least that of Ameri- can musicians. First, the claim that the premiere of the Trio in B major, Op. 8, was given not in Germany but in New York on 27 November 1855 at Dodsworth’s Hall (by the pianist William Mason, Theodor Thomas and Carl Bergmann as violinist and cellist, respectively). This was widely known in the English lit- erature long before being included in McCorkle’s Thematisches Verzeichnis—perhaps most obviously familiar from Florence May’s ascribing it “to the lasting distinction of America” in her biography of 1905, which was quoted verbatim by Daniel Gregory Mason in 1933.1 Second that the premiere of the sec- ond String Sextet, Op. 36, was in Boston, by the Mendelssohn Quintette Club on 11 October 1866. This was a less well known fact, only established in the modern literature by McCorkle and the Hofmanns.2 The first of these claims was challenged by Michael Struck in these pages in 1991 and elsewhere in 1997 by showing that the German first performance predated this by several weeks, being on Saturday, 13 October 1855, in the hall of the Gewerb- haus, Danzig.3 The second dating has never been discussed in detail in English, but was challenged and rectified by myself in the course of a paper in German for the Gmunden Kongress in the Brahms year of 1997.4 As 2016 saw the 150th anniversary of the premiere of Brahms, photograph by Atelier Adèle, Vienna, ca. -

Brahms Rhapsodizing: the Alto Rhapsody and Its Expressive Double Author(S): Christopher Reynolds Reviewed Work(S): Source: the Journal of Musicology, Vol

Brahms Rhapsodizing: The Alto Rhapsody and Its Expressive Double Author(s): Christopher Reynolds Reviewed work(s): Source: The Journal of Musicology, Vol. 29, No. 2 (Spring 2012), pp. 191-238 Published by: University of California Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/jm.2012.29.2.191 . Accessed: 10/07/2012 14:09 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Musicology. http://www.jstor.org Brahms Rhapsodizing: The Alto Rhapsody and Its Expressive Double CHristop H er R E Y noL ds For Donald C. Johns Biographers have always recognized the Alto Rhapsody to be one of Brahms’s most personal works; indeed, both the composer and Clara Schumann left several unusually specific com- ments that suggest that this poignant setting of Goethe’s text about a lonely, embittered man had a particular significance for Brahms. Clara 191 wrote in her diary that after her daughter Julie Schumann announced her engagement to an Italian count on 11 July 1869, Brahms suddenly began -

Bbwcesro! Kr/ C*

'Vttijl <<^ BBwCESro! k R/ c* 8REHB •* '1 i' 1 ft^'r Hi _ Sft" 63* Scanned from the collections of The Library of Congress AUDIO-VISUAL CONSERVATION CONGRESS at The LIBRARY of u»i Packard Campus Conservation for Audio Visual www.loc.gov/avconservation Reading Room Motion Picture and Television www.loc.gov/rr/mopic Center Recorded Sound Reference www.loc.gov/rr/record Vol. XX. (JkaS? leMOtf ttffitXT* No. 1 / I?|?Ci jbf3 c "HERE THEY ARE! I'VE ROOKED 'EM!" t"| HATS the way to talk to your people as soon as you sign your contracts for the new 3 " {Pictures (Nationally Advertised) Let everybody in your town know what's coming to your theater next season. Advertise the stars, adver- of tise the plays. Tie up with the immense campaign neitional advertising. Use the trade marks. Your whole community is asking: "Where can we " see Paramount and Artcraft pictures ? Stand up and shout the glad news— fit HERE THEY ARE!" PLATERS-LASKY CORPORATION h&MOUS .JESSEl.lASKYMh.P^.CECILB.DEMILLEa>Kftr?Me™i J ADOLPllZtU<ORi'rM rNIW YORKy jadLdUJULcfggg ZEESS <w CHICAGO July 6, 19 18 — L. icturcs Another story of dramat- ic and emotional intensity which will win new thousands of admirers for the ablest young emotional star of the screen Sflorious Jldveniure By Edith Barnard Delano Directed by Hobart Henley This production is announced as "the story of every girl's dream and one girl's triumph. A drama of love's conflict with man's selfishness." The kind of story that Mae Marsh's own tremendous public selects for her to play in.