Concert Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concert Program

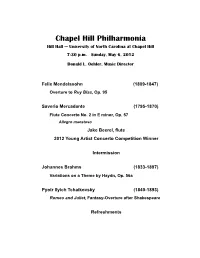

Chapel Hill Philharmonia Hill Hall — University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 7:30 p.m. Sunday, May 6, 2012 Donald L. Oehler, Music Director Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) Overture to Ruy Blas, Op. 95 Saverio Mercadante (1795-1870) Flute Concerto No. 2 in E minor, Op. 57 Allegro maestoso Jake Beerel, flute 2012 Young Artist Concerto Competition Winner Intermission Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Variations on a Theme by Haydn, Op. 56a Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) Romeo and Juliet, Fantasy-Overture after Shakespeare Refreshments Inspirations William Shakespeare conveyed the overwhelming impact of Julius Caesar in imperial Rome: “Why, man, he doth bestride the narrow world like a Colussus.” So might 19th century composers have viewed the figure of Ludwig van Beethoven. With his Symphony No. 3, known as Eroica, composed in 1803, Beethoven radically altered the evolution of symphonic music. The work was inspired by Napoléon Bonaparte’s republican ideals while rejecting that ‘hero’s’ assumption of an imperial mantle. Beethoven broke precedent by employing his art “as a vehicle to convey beliefs,” expanding beyond compositional technique to add the “dimension of meaning and interpretation. All the more remarkable…the high priest of absolute music, effected this change.” (composer W.A. DeWitt) Beethoven, in a word, brought Romanticism to the concert hall, “replac[ing] the Enlightenment cult of reason with a cult of instinct, passion, and the creative genius as virtual demigod. The Romantics seized upon Beethoven’s emotionalism, his sense of the individual as hero.” (composer/writer Jan Swafford) The expression of this new sensibility took many forms, ranging from intensified expression within classical forms, exemplified by Felix Mendelssohn or Johannes Brahms, to the unbridled fervor of Piyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, the revolutionary virtuosity and structural innovations of Franz Liszt, the hallucinatory visions of Hector Berlioz, and the megalomania of Richard Wagner. -

Monday, June 30Th at 7:30 P.M. Blue Lake Fine Arts Camp Free Admission

JUNE 2008 Listener BLUE LAKE PUBLIC RADIO PROGRAM GUIDE Monday, June 30th at 7:30 p.m. TheBlue Grand Lake Rapids Fine ArtsSymphony’s Camp DavidFree LockingtonAdmission WBLV-FM 90.3 - MUSKEGON & THE LAKESHORE WBLU-FM 88.9 - GRAND RAPIDS A Service of Blue Lake Fine Arts Camp 231-894-5656 http://www.bluelake.org J U N E 2 0 0 8 H i g h l i g h t s “Listener” Volume XXVI, No.6 “Listener” is published monthly by Blue Lake Public Radio, Route Two, Twin Lake, MI 49457. (231)894-5656. Summer at Blue Lake WBLV, FM-90.3, and WBLU, FM-88.9, are owned and Summer is here and with it a terrific live from operated by Blue Lake Fine Arts Camp Blue Lake and broadcast from the Rosenberg- season of performances at Blue Lake Fine Clark Broadcast Center on Blue Lake’s Arts Camp. Highlighting this summer’s Muskegon County Campus. WBLV and WBLU are public, non-commercial concerts is a presentation of Beethoven’s stations. Symphony No. 9, the Choral Symphony, Blue Lake Fine Arts Camp with the Blue Lake Festival Orchestra, admits students of any race, color, Festival Choir, Domkantorei St. Martin from national or ethnic origin and does not discriminate in the administration of its Mainz, Germany, and soloists, conducted programs. by Professor Mathias Breitschaft. The U.S. BLUE LAKE FINE ARTS CAMP Army Field Band and Soldier’s Chorus BOARD OF TRUSTEES will present a free concert on June 30th, and Jefferson Baum, Grand Haven A series of five live jazz performances John Cooper, E. -

Opis Programa Diplomskog Ispita Diplomski Rad

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Zagreb Repository SVEUČILIŠTE U ZAGREBU MUZIČKA AKADEMIJA VI. ODSJEK IVANA ČULJAK OPIS PROGRAMA DIPLOMSKOG ISPITA DIPLOMSKI RAD ZAGREB, 2018. SVEUČILIŠTE U ZAGREBU MUZIČKA AKADEMIJA VI. ODSJEK OPIS PROGRAMA DIPLOMSKOG ISPITA DIPLOMSKI RAD Mentor: nasl. doc. art. Martin Draušnik Student: Ivana Čuljak Odsjek: VI. odsjek Smjer: Violina Ak. god. 2017/2018 ZAGREB, 2018. DIPLOMSKI RAD ODOBRIO MENTOR nasl. doc. art. Martin Draušnik _________________________ (potpis) U Zagrebu, _________________________ Diplomski rad obranjen________________ Ocjena ____________________________ POVJERENSTVO: 1.__________________________ 2.__________________________ 3._________________________ 4._________________________ 5._________________________ OPASKA: PAPIRNATA KOPIJA RADA DOSTAVLJENA JE ZA POHRANU KNJIŽNICI MUZIČKE AKADEMIJE SAŽETAK Ovaj rad bavi se opisom programa mog diplomskog koncerta. Rad je podijeljen na više poglavlja u kojima ću sažeto obraditi karakteristike skladatelja, te opis skladbi koje ću izvoditi na diplomskom ispitu u obliku opširne programske knjižice. Ključne riječi: diplomski rad, programska knjižica, violina ABSTRACT This paper deals with the description of my graduate concert. The paper is divided in chapters in wich I will give insight into composers characteristics and description of the pieces I will preform in my graduate concert, all written in form of lenghtly program notes. Key words: thesis, program notes, violin SADRŽAJ 1. Uvod 1 2. J. S. Bach; druga partita za solo violinu u d-molu, BWV 1004 2 2.1. Chaconne 3 3. W. A. Mozart 5 3.1. Koncert za violinu i orkestar u G-duru, br.3, K.216; Adagio, Rondeau 6 4. J. Brahms 7 4.1. Sonata za violinu i klavir u d-molu, br.3, op.108 8 5. -

Program Notes

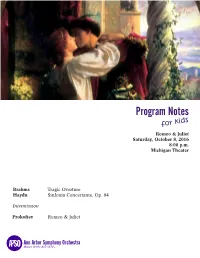

Program Notes for kids Romeo & Juliet Saturday, October 8, 2016 8:00 p.m. Michigan Theater Brahms Tragic Overture Haydn Sinfonia Concertante, Op. 84 Intermission Prokofiev Romeo & Juliet Tragic Overture by Johannes Brahms What kind of piece is this? This piece is a concert overture, similar to the overture of an opera. An opera overture is the opening instrumental movement that signals to the audience that the perfor- mance is about to begin. Similarily, a concert overture is a short and lively introduction to an instrumental con- cert. When was it written? Brahms wrote this piece in the summer of 1880 while on vacation. Brahms at the Piano What is it about? Brahms was a quiet and sad person, and really wanted to compose a piece about a tragedy. With no particular tragedy in mind, he created this overture as a contrast to his much happier Academic Festival Overture, which he completed in the same summer. When describing the two overtures to a friend, Brahms said “One of them weeps, the other laughs.” About the Composer Fun Facts Johannes Brahms | Born May 7, 1833 in Hamburg, Ger- Brahms never really grew up. He didn’t many | Died April 3, 1897 in Vienna, Austria care much about how he looked, he left his clothes lying all over the floor Family & Carfeer of his house, he loved merry-go-rounds and circus sideshows, and he continued Brahms’ father, Johann Jakob Brahms, was a bierfiedler: playing with his childhood toys until he literally, a “beer fiddler” who played in small bands at was almost 30 years old. -

The Role of Clarinet in Op. 114 a Minor Trio Composed by Johannes Brahms for Clarinet, Cello and Piano

Global Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences Vol.7, No. 3, pp.80-90, March 2019 Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) THE ROLE OF CLARINET IN OP. 114 A MINOR TRIO COMPOSED BY JOHANNES BRAHMS FOR CLARINET, CELLO AND PIANO *İlkay Ak Lecturer, Music Department, Anadolu University, Eskişehir, Turkey ABSTRACT: Sonatas and chamber music works written for clarinetist Richard Mühlfeld by Johannes Brahms, who was one of the most important composers of the second half of Romantic period, in the last years of his life are among the irreplaceable works of clarinet training repertoire. These works which enable the musical improvement for the player are also significant to transfer the stylistic properties of the time. Op. 114 A Minor Trio composed for Clarinet, Cello and Piano by Brahms is among the most important works of chamber music training repertoire and often appears in concerts. The work consists of four parts. The first part is Allegro, the second part is Adagio, the third one is Andantino grazioso and the fourth one is Allegro. In this study, the life and musical identity of Brahms are going to be discussed first and then solo and chamber music works with clarinet are going to be mentioned. Next, the parts which can create technical and musical difficulties for the clarinet performance in Op. 114 A Minor Trio of the composer are determined and the things to decrease these are going to be suggested. KEYWORDS: Romantic Period, Brahms, Mühlfeld, Clarinet, Trio INTRODUCTION: JOHANNES BRAHMS Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) German Johannes Brahms as one of the prominent composers of the second half of 19th century was born on 7 May 1833 as a son of a double bass player. -

We Are TEN – in This Issue

RVW No.31 NEW 2004 Final 6/10/04 10:36 Page 1 Journal of the No.31 October 2004 EDITOR Stephen Connock RVW (see address below) Society We are TEN – In this issue... and still growing! G What RVW means to me Testimonials by sixteen The RVW Society celebrated its 10th anniversary this July – just as we signed up our 1000 th new members member to mark a decade of growth and achievement. When John Bishop (still much missed), Robin Barber and I (Stephen Connock) came together to form the Society our aim was to widen from page 4 appreciation of RVW’s music, particularly through recordings of neglected but high quality music. Looking back, we feel proud of what we have achieved. G 49th Parallel World premieres Through our involvement with Richard Hickox, and Chandos, we have stimulated many fine world by Richard Young premiere recordings, including The Poisoned Kiss, A Cotswold Romance, Norfolk Rhapsody No.2, page 14 The Death of Tintagiles and the original version of A London Symphony. Our work on The Poisoned Kiss represents a special contribution as we worked closely with Ursula Vaughan Williams on shaping the libretto for the recording. And what beautiful music there is! G Index to Journals 11-29 Medal of Honour The Trustees sought to mark our Tenth Anniversary in a special way and decided to award an International Medal of Honour to people who have made a remarkable contribution to RVW’s music. The first such Award was given to Richard Hickox during the concert in Gloucester and more . -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College Analyses

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE ANALYSES OF ORGAN ETUDES OPP. 38, 66 AND 72 BY RACHEL LAURIN A DOCUMENT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By SILVIYA MATEVA Norman, Oklahoma 2016 ANALYSES OF ORGAN ETUDES OPP. 38, 66 AND 72 BY RACHEL LAURIN A DOCUMENT APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC BY ______________________________ Dr. John Schwandt, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Sarah Ellis ______________________________ Dr. Eugene Enrico ______________________________ Dr. Vicki Schaeffer ______________________________ Dr. Maeghan Hennessey © Copyright by SILVIYA MATEVA 2016 All Rights Reserved. Table of Contents List of Tables …………………………………………………………………………... v List of Examples …………………………………………………………………….…. v Abstract ……………………………………………………………………………… viii Introduction………………………….………………………………………………..... 1 Chapter 1: Rachel Laurin: Biography.……..…………………………………………… 2 Chapter 2: Ken Cowan and Isabelle Demers: The relationship between composer and commissioners……...…..……………………………………………….…….... 9 Chapter 3: Analyses of Etudes Opp. 38, 66 and 72….………………………………... 19 Étude Héroïque, Op. 38……………………………………………………….. 21 Étude-Caprice, Op. 66………………………………………………………… 44 Symphonic Etude for Solo Pedal, Op. 72……………………………………... 64 Chapter 4: Conclusion……….....…………………………………………………..... 101 Bibliography…………………………………...…………………………………...... 106 Appendix: Organ Works by Rachel Laurin………………………………………….. 107 iv List of Tables Table 1. Op. 38, section outline ………………………………………………….…… 22 Table 2. Op. 66, section outline ………………………………………………...…….. 45 Table 3. Op. 72, Isabelle Demers’ name inscription in variation titles ……………..... 65 Table 4. Op. 72, tonal and metrical outline of the variations ………………………… 99 List of Examples Example 1. Op. 38, mm. 1-8 …………………………………………….…………… 24 Example 2. Op. 38, mm. 15-17 ………………………………………………………. 25 Example 3. Op. 38, mm. 24-31 ………………………………………………………. 26 Example 4. Op. 38, mm. 34-38 ………………………………………………………. 28 Example 5. Op. 38, mm. 38-43 ………………………………………………………. 29 Example 6. Op. 38, mm. -

Concert Program Interpreters

Concert Program Interpreters Harnackhaus, June 11, 7 p.m. Kammerchor der Auenkirche The Chamber Choir of Auenkirche is a semi-professional vocal ensemble that presents sacred and secular music at a high level of musical excellence – under Vocal Ensemble: Kammerchor der Auenkirche the professional leadership of Jörg Strodthoff. The wide repertoire includes Conduction & Piano: Jörg Strodthoff among others works by Johann Sebastian Bach, Johannes Brahms, Orlando di Lasso, Felix Mendelssohn, Max Reger, Johann Schein, Heinrich Schütz, and Tho- Treble Recorder: Andrea Wissel-Romefort mas Weelkes. Johann Christian Schickardt (1682 - 1762) Jörg Strodthoff Sonata for treble recorder and basso continuo, d minor, op. 1, no. 2 Jörg Strodthoff received a broad training in piano, song accompaniment, har- (Adagio, Grave, Allemanda) mony and counterpoint, composition and choral conducting at the Hanover Uni- versity of Music and Drama. From 1986 he led the orchestra of the Medical School in Hanover and received a teaching position at the University of Göttingen Daniel Friderici (1584 - 1638) (harmony and counterpoint). Parallel a concert career as organist, harpsichordist "Drei schöne Dinge fein", folk song, in "Servia musicalis" (Musikalisches and pianist for song accompaniment and chamber music evolved. In 1989, he Sträußlein), Lübeck 1617 received a call to the traditional A-position as church musician of the Auenkirche in Berlin-Wilmersdorf. His priorities include, in addition to shaping of worship, Hans Leo Haßler (1564 - 1612) leadership of the choir – with regular performances of the works of classical ora- "Cantate domino", motet torio literature -, the chamber choir and the brass circle, as well as artistic organ playing and improvisation at the historical organ. -

Music Academy of the West Archives PA Mss 65

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt9m3nd615 No online items Guide to the Music Academy of the West archives PA Mss 65 Finding aid prepared by David Seubert and Danielle Hoffman, 2007; revised by Zachary Liebhaber, 2019. UC Santa Barbara Library, Department of Special Research Collections University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara 93106-9010 [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucsb.edu/special-collections 2007; 2019 Guide to the Music Academy of PA Mss 65 1 the West archives PA Mss 65 Title: Music Academy of the West archives Identifier/Call Number: PA Mss 65 Contributing Institution: UC Santa Barbara Library, Department of Special Research Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 102 linear feet(117 document boxes, 19 half document boxes, 784 audiotape reels, 38 videocassettes) Date (inclusive): 1946-2014 Abstract: Audio and video recordings of Music Academy of the West concerts, recitals and masterclasses dating from 1961 to 2001, as well as Music Academy of the West organizational records dating from 1946 to 2012. Physical Location: Special Research Collections, UC Santa Barbara Library Access Restrictions The collection is open for research. Access copies must be made before listening to recordings. Use Restrictions Copyright has not been assigned to the Department of Special Research Collections, UCSB. All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Research Collections. Permission for publication is given on behalf of the Department of Special Research Collections as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission of the copyright holder, which also must be obtained. -

Brahms's Double Concerto

BRAHMS’S DOUBLE CONCERTO ACO HomeCasts | 7 May 2020 HOMECASTS: ACO IN CONCERT 2 Inside you’ll find features and interviews that shine a spotlight on our players and the music you are about to hear. Enjoy the read. INSIDE: Welcome Wesfarmers Arts The Double Concerto From the ACO’s Managing A message from our Your five-minute read Director Richard Evans ACO HomeCasts Partner on the music p.3 p.5 p.8 Musical Accents ACO HomeCasts Acknowledgments Andrew Ford on What’s coming up in The ACO thanks our nationalism in music our digital season generous supporters p.13 p.30 p.33 AUSTRALIAN CHAMBER ORCHESTRA 3 MANAGING DIRECTOR WELCOME Thank you for joining us for our ACO In Concert stream of Brahms’s Double Concerto, which was filmed live at our ‘Brahms & Dvorˇák’ concert at the Sydney Opera House in 2019. Whilst we are unable to join you in the concert hall as we usually would, we are committed to providing you with innovative and inspirational music experiences through our digital season, ACO HomeCasts. This concert is one of many that we will be bringing to you over the coming months, along with our Home to Home videos (direct from the homes of our musicians), our education videos and podcasts, musician-curated Spotify playlists, and so much more. If you haven’t yet had the chance to explore ACO HomeCasts, I encourage you to visit our website to delve into some of our most recent releases and to discover what’s coming up. The COVID-19 crisis is devastating the economic and performance fabric of our national arts sector. -

Edition 1 | 2019-2020

Contents CONCERT EXPERIENCE Robert Moody, Music Director ........................................................................................... 4 Kalena Bovell, Assistant Conductor ................................................................................. 6 Memphis Youth Symphony Program................................................................................ 8 Memphis Symphony Orchestra .......................................................................................10 Letter from Peter Abell, CEO ...........................................................................................15 Memphis Symphony Chorus ...........................................................................................16 “Tommy Dorsey” Concerto and Scheherazade ..........................................................19 Mozart and Beethoven .....................................................................................................27 The Three Bs!......................................................................................................................37 Handel’s Messiah ...............................................................................................................42 Magic of Memphis! ............................................................................................................51 Finlandia, Mahler 4, and a Rising Star! .........................................................................53 PATRON EXPERIENCE Tunes and Tales ..................................................................................................................62 -

1 the Following Is an Alphabetical List of Important Classical Composers

The following is an alphabetical list of important classical composers. Following the composer’s name is the birth and death years and the composer’s nationality. At the end of the list, I have mentioned some important groups of composers which you need to know. These are standard groupings, and the composers are often referred to in these manners. A word of caution: some of the names – particularly the Russians – you will often find spelled in a variety of ways. For example: Tchaikovsky, Tchaikofsky, Chaikofskii, Tchaikovskii, etc. Similarly, some works are known under various names (e.g., in translation and/or in the original language). Some are known equally well by both! (For example, Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring). Some of the more common translations I have provided for you (not all). Keep in mind as you build your recording collection that you might have to look for something under a different title! Though the list goes from 1098 to the present, it is ridiculously incomplete, and in fact is not meant to be complete. Many, many fine – and even important – composers are not listed. These include, for example, Alexander Zemlinsky, Leonard Bernstein, Luigi Nono, Fanny Mendelssohn, Josquin des Prez, and Alma Mahler, to name only a very few. There are two ways that a composer got onto the list. Either they are so important that they were categorized as a “no-brainer” inclusion (e.g., Beethoven, Mozart, Brahms), or they are not tremendously important, but wrote some work or works which are MAJOR repertoire staples (this is how Dukas and Franck, for example, made the list).