Celia & Johnny

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exile: Cuba and the United States

Lesson Plan: Exile: Cuba and the United States Grade Level 9-12 Objective Understand the events of the Cuban revolution and their effect on U.S.-Cuban relations and U.S. foreign policy. National History Standards Historical Thinking Standards, 5-12 • Standard 1: Chronological Thinking • Standard 4: Historical Research Capabilities • Standard 5: Historical Issues Analysis and Decision-Making Content Standards, 5-12 • Era 9: Postwar United States o Standard 2B: The student understands United States foreign policy in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America. Evaluate changing foreign policy toward Latin America. Time Two class periods Background Over the course of a career that spanned six decades and took her from humble beginnings in Havana, Cuba, to acclaim as a world-renowned artist, Celia Cruz became the undisputed Queen of Latin Music. Combining a piercing and powerful voice with a larger-than-life personality and stage costumes, she was one of the few women to succeed in the male-dominated world of salsa music. The 1950s were a time of great turmoil in Cuba. The political landscape had changed dramatically with the imminent revolution, and musicians faced constant changes that affected various aspects of their lives. Celia Cruz had traveled to the United States and Latin America often during the 1940s and 1950s. At the end of 1959, the manager of the Sonora Matancera (the band with which Cruz had been performing) secured a one-year contract to perform in Mexico. Cruz decided to go with the band; they left on July 15, 1960, six months after Fidel Castro came to power in Cuba, and never returned. -

Malpaso Dance Company Is Filled with Information and Ideas That Support the Performance and the Study Unit You Will Create with Your Teaching Artist

The Joyce Dance Education Program Resource and Reference Guide Photo by Laura Diffenderfer The Joyce’s School & Family Programs are supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council; and made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. Special support has been provided by Con Edison, The Walt Disney Company, A.L. and Jennie L. Luria Foundation, and May and Samuel Rudin Family Foundation, Inc. December 10, 2018 Dear Teachers, The resource and reference material in this guide for Malpaso Dance Company is filled with information and ideas that support the performance and the study unit you will create with your teaching artist. For this performance, Malpaso will present Ohad Naharin’s Tabla Rasa in its entirety. Tabula Rasa made its world premiere on the Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre on February 6, 1986. Thirty-two years after that first performance, on May 4, 2018, this seminal work premiered on Malpaso Dance Company in Cuba. Check out the link here for the mini-documentary on Ohad Naharin’s travels to Havana to work with Malpaso. This link can also be found in the Resources section of this study guide. A new work by company member Beatriz Garcia Diaz will also be on the program, set to music by the Italian composer Ezio Bosso. The title of this work is the Spanish word Ser, which translates to “being” in English. I love this quote by Kathleen Smith from NOW Magazine Toronto: "As the theatre begins to vibrate with accumulated energy, you get the feeling that they could dance just about any genre with jaw-dropping style. -

Redalyc.Mambo on 2: the Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City

Centro Journal ISSN: 1538-6279 [email protected] The City University of New York Estados Unidos Hutchinson, Sydney Mambo On 2: The Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City Centro Journal, vol. XVI, núm. 2, fall, 2004, pp. 108-137 The City University of New York New York, Estados Unidos Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=37716209 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Hutchinson(v10).qxd 3/1/05 7:27 AM Page 108 CENTRO Journal Volume7 xv1 Number 2 fall 2004 Mambo On 2: The Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City SYDNEY HUTCHINSON ABSTRACT As Nuyorican musicians were laboring to develop the unique sounds of New York mambo and salsa, Nuyorican dancers were working just as hard to create a new form of dance. This dance, now known as “on 2” mambo, or salsa, for its relationship to the clave, is the first uniquely North American form of vernacular Latino dance on the East Coast. This paper traces the New York mambo’s develop- ment from its beginnings at the Palladium Ballroom through the salsa and hustle years and up to the present time. The current period is characterized by increasing growth, commercialization, codification, and a blending with other modern, urban dance genres such as hip-hop. [Key words: salsa, mambo, hustle, New York, Palladium, music, dance] [ 109 ] Hutchinson(v10).qxd 3/1/05 7:27 AM Page 110 While stepping on count one, two, or three may seem at first glance to be an unimportant detail, to New York dancers it makes a world of difference. -

Howard Levy Full Bio

Howard Levy Full Bio The Early Years Howard Levy began playing piano at age 8. He started improvising after his 3rd piano lesson, and would often improvise for 30 minutes or more. His parents enrolled him in the prep division of the Manhattan School of Music, where he studied piano for 4 years with Jean Graham, and also studied music theory. When Howard was 11, The Manhattan School recommended that he study composition with Nadia Boulanger in Paris. A place for him was guaranteed, but neither he nor his parents wanted him to disrupt his life at age 11 and move to Europe for a year. Howard had a deep love for classical music, but around age 12 he started to become interested in many other styles of music - pop, folk, rock and roll, then Blues and Jazz. While in high school in New York City, Howard won his school’s “Lincoln Center Award”, given to the outstanding musician in the school. He also studied Bach on the pipe organ for 2 years. This was a major influence that has continued to this day. 4 years ago, Howard received his high school’s “Distinguished Alumni” Award. While in high school, he composed “Extension Chord”, an odd- time meter Jazz piece using Indian rhythmic formulas. He eventually recorded this in 2008, with German bass clarinetist Michael Riessler and French accordionist Jean-Louis Matinier on their Enja CD “Silver and Black”. Howard attended Northwestern University, where he played piano in the university’s Jazz Band, led by jazz musicians Bunky Green and Rufus Reid. -

Samba, Rumba, Cha-Cha, Salsa, Merengue, Cumbia, Flamenco, Tango, Bolero

SAMBA, RUMBA, CHA-CHA, SALSA, MERENGUE, CUMBIA, FLAMENCO, TANGO, BOLERO PROMOTIONAL MATERIAL DAVID GIARDINA Guitarist / Manager 860.568.1172 [email protected] www.gozaband.com ABOUT GOZA We are pleased to present to you GOZA - an engaging Latin/Latin Jazz musical ensemble comprised of Connecticut’s most seasoned and versatile musicians. GOZA (Spanish for Joy) performs exciting music and dance rhythms from Latin America, Brazil and Spain with guitar, violin, horns, Latin percussion and beautiful, romantic vocals. Goza rhythms include: samba, rumba cha-cha, salsa, cumbia, flamenco, tango, and bolero and num- bers by Jobim, Tito Puente, Gipsy Kings, Buena Vista, Rollins and Dizzy. We also have many originals and arrangements of Beatles, Santana, Stevie Wonder, Van Morrison, Guns & Roses and Rodrigo y Gabriela. Click here for repertoire. Goza has performed multiple times at the Mohegan Sun Wolfden, Hartford Wadsworth Atheneum, Elizabeth Park in West Hartford, River Camelot Cruises, festivals, colleges, libraries and clubs throughout New England. They are listed with many top agencies including James Daniels, Soloman, East West, Landerman, Pyramid, Cutting Edge and have played hundreds of weddings and similar functions. Regular performances in the Hartford area include venues such as: Casona, Chango Rosa, La Tavola Ristorante, Arthur Murray Dance Studio and Elizabeth Park. For more information about GOZA and for our performance schedule, please visit our website at www.gozaband.com or call David Giardina at 860.568-1172. We look forward -

MIC Buzz Magazine Article 10402 Reference Table1 Cuba Watch 040517 Cuban Music Is Caribbean Music Not Latin Music 15.Numbers

Reference Information Table 1 (Updated 5th June 2017) For: Article 10402 | Cuba Watch NB: All content and featured images copyrights 04/05/2017 reserved to MIC Buzz Limited content and image providers and also content and image owners. Title: Cuban Music Is Caribbean Music, Not Latin Music. Item Subject Date and Timeline Name and Topic Nationality Document / information Website references / Origins 1 Danzon Mambo Creator 1938 -- One of his Orestes Lopez Cuban Born n Havana on December 29, 1911 Artist Biography by Max Salazar compositions, was It is known the world over in that it was Orestes Lopez, Arcano's celloist and (Celloist and pianist) broadcast by Arcaño pianist who invented the Danzon Mambo in 1938. Orestes's brother, bassist http://www.allmusic.com/artist/antonio-arcaño- in 1938, was a Israel "Cachao" Lopez, wrote the arrangements which enables Arcano Y Sus mn0001534741/biography Maravillas to enjoy world-wide recognition. Arcano and Cachao are alive. rhythmic danzón Orestes died December 1991 in Havana. And also: entitled ‘Mambo’ In 29 August 1908, Havana, Cuba. As a child López studied several instruments, including piano and cello, and he was briefly with a local symphony orchestra. His Artist Biography by allmusic.com brother, Israel ‘Cachao’ López, also became a musician and influential composer. From the late 20s onwards, López played with charanga bands such as that led by http://www.allmusic.com/artist/orestes-lopez- Miguel Vásquez and he also led and co-led bands. In 1937 he joined Antonio mn0000485432 Arcaño’s band, Sus Maravillas. Playing piano, cello and bass, López also wrote many arrangements in addition to composing some original music. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E684 HON

E684 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks March 17, 2009 TRIBUTE TO KENT OLSON, EXECU- Not only will this initiative increase Internet Madam Speaker, I encourage my col- TIVE DIRECTOR OF THE PROFES- speed and accessibility for customers, but per- leagues to join me in wishing my brothers of SIONAL INSURANCE AGENTS OF haps more importantly it will create 3,000 new Omega Psi Phi Fraternity a successful political NORTH DAKOTA jobs. summit as these men continue to build a Over the next ten years, AT&T also plans to strong and effective force of men dedicated to HON. EARL POMEROY create or save an additional one thousand its Cardinal Principles of manhood, scholar- jobs through a plan to invest $565 million in OF NORTH DAKOTA ship, perseverance, and uplift. replacing its current fleet of vehicles with IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES f 15,000 domestically manufactured Com- Tuesday, March 17, 2009 pressed Natural Gas and alternative fuel vehi- REMEMBERING THE LIFE OF Mr. POMEROY. Madam Speaker, I rise to cles. MUSIC IMPRESARIO RALPH honor the distinguished career of Kent Olson. Research shows that this new fleet will save MERCADO I am pleased to have known Kent Olson for 49 million gallons of gasoline over the next ten the many years he served as the Executive years. It also will reduce carbon emissions by HON. CHARLES B. RANGEL Director of the Professional Insurance Agents 211,000 metric tons in this same time frame. OF NEW YORK of North Dakota working with him on important Madam Speaker, I applaud AT&T for its ini- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES tiative in taking the lead in the movement to insurance issues for North Dakota farmers. -

Music at Lehman College Dr

Panel Featuring: Students and Faculty of the Celia Cruz Bronx High School of Music Eganam Segbefia, Award Winning Trumpeter Moderated by Victoria Smith ('20) and Dania Miguel ('21) 2019 The 2019 Pacheco Festival Commemorative Program Current and Past Festival Events The Johnny Pacheco Latin Music Dr. Johnny Pacheco and Jazz Festival at Lehman College For decades, Johnny Pacheco has been at the center of the Latin m u s i c u n i v e r s e . H i s n i n e G r a m m y nominations, ten Gold records and numerous Mission Statement: awards pay tribute to his creative talent as composer, arranger, bandleader, and producer. The Johnny Pacheco Latin Music and Jazz Festival at Lehman College is Moreover, he is the pioneer of an unforgettable an annual event which provides performance and learning opportunities for musical era that changed the face of tropical talented young musicians who are studying music in New York City music history, the Fania All-Stars era. schools. The Pacheco Festival is committed to developing a world-wide Throughout his 40-year involvement with the development of Latin music, Johnny Pacheco audience via live Internet streaming and other forms of broadcast media. has received many kudos for his extraordinary genius. In November of 1998, he was inducted into the International Latin Music Hall of Fame. In 1997, he was the recipient of the Bobby Capo' Lifetime Achievement Award, awarded by Governor George Pataki. In 1996 the president of the Dominican Republic, Juaquin Balaguer 2018 Pacheco Festival Memories bestowed him with the prestigious Presidential Medal of Honor. -

Annual AT&T San Jose Jazz Summer Fest Friday, August 12

***For Immediate Release*** 22nd Annual AT&T San Jose Jazz Summer Fest Friday, August 12 - Sunday, August 14, 2011 Plaza de Cesar Chavez Park, Downtown San Jose, CA Ticket Info: www.jazzfest.sanjosejazz.org Tickets: $15 - $20, Children Under 12 Free "The annual San Jose Jazz [Summer Fest] has grown to become one of the premier music events in this country. San Jose Jazz has also created many educational programs that have helped over 100,000 students to learn about music, and to become better musicians and better people." -Quincy Jones "Folks from all around the Bay Area flock to this giant block party… There's something ritualesque about the San Jose Jazz [Summer Fest.]" -Richard Scheinan, San Jose Mercury News "San Jose Jazz deserves a good deal of credit for spotting some of the region's most exciting artists long before they're headliners." -Andy Gilbert, San Jose Mercury News "Over 1,000 artists and 100,000 music lovers converge on San Jose for a weekend of jazz, funk, fusion, blues, salsa, Latin, R&B, electronica and many other forms of contemporary music." -KQED "…the festival continues to up the ante with the roster of about 80 performers that encompasses everything from marquee names to unique up and comers, and both national and local acts...." -Heather Zimmerman, Silicon Valley Community Newspapers San Jose, CA - June 15, 2011 - San Jose Jazz continues its rich tradition of presenting some of today's most distinguished artists and hottest jazz upstarts at the 22nd San Jose Jazz Summer Fest from Friday, August 12 through Sunday, August 14, 2011 at Plaza de Cesar Chavez Park in downtown San Jose, CA. -

David Amram in Denver May 10 - 13

David Amram in Denver May 10 - 13 * David Amram has composed more than 100 orchestral and chamber music works, written many scores for Broadway theater and film, including the classic scores for the films Splendor in The Grass and The Manchurian Candidate; two operas, including the ground-breaking Holocaust opera The Final Ingredient; and the score for the landmark 1959 documentary Pull My Daisy, narrated by novelist Jack Kerouac. He is also the author of two books, Vibrations, an autobiography, and Offbeat: Collaborating With Kerouac, a memoir. A pioneer player of jazz French horn, he is also a virtuoso on piano, numerous flutes and whistles, percussion, and dozens of folkloric instruments from 25 countries, as well as an inventive, funny improvisational lyricist. He has collaborated with Leonard Bernstein, who chose him as The New York Philharmonic's first composer-in-residence in 1966, Langston Hughes, Dizzy Gillespie, Dustin Hoffman, Willie Nelson, Thelonious Monk, Odetta, Elia Kazan, Arthur Miller, Charles Mingus, Lionel Hampton, E. G. Marshall, and Tito Puente. Amram's most recent work Giants of the Night is a flute concerto dedicated to the memory Charlie Parker, Jack Kerouac and Dizzy Gillespie, three American artists Amram knew and worked with. It was commissioned and recently premiered by Sir James Galway, who also plans to record it. Today, as he has for over fifty years, Amram continues to compose music while traveling the world as a conductor, soloist, bandleader, visiting scholar, and narrator in five languages. He is also currently working with author Frank McCourt on a new setting of the Mass, Missa Manhattan, as well as on a symphony commissioned by the Guthrie Foundation, Symphonic Variations on a Theme by Woody Guthrie. -

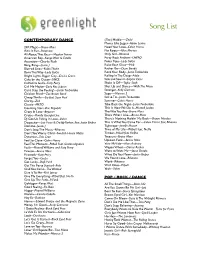

Greenlight's Complete Song List

Song List CONTEMPORARY DANCE (The) Middle—-Zedd Moves Like Jagger--Adam Levine 24K Magic—Bruno Mars Need Your Love--Calvin Harris Ain’t It Fun--Paramore No Roots—Alice Merton All About That Bass—Meghan Trainor Only Girl--Rihanna American Boy--Kanye West & Estelle Party Rock Anthem--LMFAO Attention—Charlie Puth Poker Face--Lady GaGa Bang, Bang—Jessie J Raise Your Glass—Pink Blurred Lines--Robin Thicke Rather Be—Clean Bandit Born This Way--Lady GaGa Rock Your Body--Justin Timberlake Bright Lights, Bigger City--Cee-Lo Green Rolling In The Deep--Adele Cake by the Ocean--DNCE Safe and Sound--Capitol Cities California Gurls--Katy Perry Shake It Off—Taylor Swift Call Me Maybe--Carly Rae Jepson Shut Up and Dance—Walk The Moon Can’t Stop the Feeling!—Justin Timberlake Stronger--Kelly Clarkson Chicken Fried—Zac Brown Band Sugar—Maroon 5 Cheap Thrills—Sia feat. Sean Paul Suit & Tie--Justin Timberlake Clarity--Zed Summer--Calvin Harris Classic--MKTO Take Back the Night--Justin Timberlake Counting Stars-One Republic This Is How We Do It--Montell Jordan Crazy In Love--Beyonce The Way You Are--Bruno Mars Cruise--Florida Georgia Line That’s What I Like—Bruno Mars DJ Got Us Falling In Love--Usher There’s Nothing Holdin’ Me Back—Shawn Mendes Despacito—Luis Fonsi & Daddy Yankee, feat. Justin Bieber This Is What You Came For—Calvin Harris feat. Rihanna Domino--Jessie J Tightrope--Janelle Monae Don’t Stop The Music--Rihanna Time of My Life—Pitbull feat. NeYo Don’t You Worry Child--Swedish House Mafia Timber--Pitbull feat. -

The Media and Reserve Library, Located on the Lower Level West Wing, Has Over 9,000 Videotapes, Dvds and Audiobooks Covering a Multitude of Subjects

Libraries MUSIC The Media and Reserve Library, located on the lower level west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 24 Etudes by Chopin DVD-4790 Anna Netrebko: The Woman, The Voice DVD-4748 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 Anne Sophie Mutter: The Mozart Piano Trios DVD-6864 25th Anniversary Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Concerts DVD-5528 Anne Sophie Mutter: The Mozart Violin Concertos DVD-6865 3 Penny Opera DVD-3329 Anne Sophie Mutter: The Mozart Violin Sonatas DVD-6861 3 Tenors DVD-6822 Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers: Live in '58 DVD-1598 8 Mile DVD-1639 Art of Conducting: Legendary Conductors of a Golden DVD-7689 Era (PAL) Abduction from the Seraglio (Mei) DVD-1125 Art of Piano: Great Pianists of the 20th Century DVD-2364 Abduction from the Seraglio (Schafer) DVD-1187 Art of the Duo DVD-4240 DVD-1131 Astor Piazzolla: The Next Tango DVD-4471 Abstronic VHS-1350 Atlantic Records: The House that Ahmet Built DVD-3319 Afghan Star DVD-9194 Awake, My Soul: The Story of the Sacred Harp DVD-5189 African Culture: Drumming and Dance DVD-4266 Bach Performance on the Piano by Angela Hewitt DVD-8280 African Guitar DVD-0936 Bach: Violin Concertos DVD-8276 Aida (Domingo) DVD-0600 Badakhshan Ensemble: Song and Dance from the Pamir DVD-2271 Mountains Alim and Fargana Qasimov: Spiritual Music of DVD-2397 Ballad of Ramblin' Jack DVD-4401 Azerbaijan All on a Mardi Gras Day DVD-5447 Barbra Streisand: Television Specials (Discs 1-3)