Profit and Purpose in Farming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

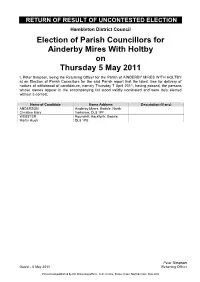

Return of Result of Uncontested Election

RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Hambleton District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Ainderby Mires With Holtby on Thursday 5 May 2011 I, Peter Simpson, being the Returning Officer for the Parish of AINDERBY MIRES WITH HOLTBY at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 7 April 2011, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) ANDERSON Ainderby Myers, Bedale, North Christine Mary Yorkshire, DL8 1PF WEBSTER Roundhill, Hackforth, Bedale, Martin Hugh DL8 1PB Dated Friday 5 September 2014 Peter Simpson Dated – 5 May 2011 Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Civic Centre, Stone Cross, Northallerton, DL6 2UU RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Hambleton District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Aiskew - Aiskew on Thursday 5 May 2011 I, Peter Simpson, being the Returning Officer for the Parish Ward of AISKEW - AISKEW at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish Ward report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 7 April 2011, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) LES Forest Lodge, 94 Bedale Road, Carl Anthony Aiskew, Bedale -

Henges in Yorkshire

Looking south across the Thornborough Henges. SE2879/116 NMR17991/01 20/5/04. ©English Heritage. NMR Prehistoric Monuments in the A1 Corridor Information and activities for teachers, group leaders and young archaeologists about the henges, cursus, barrows and other monuments in this area Between Ferrybridge and Catterick the modern A1 carries more than 50,000 vehicles a day through West and North Yorkshire. It passes close to a number of significant but often overlooked monuments that are up to 6,000 years old. The earliest of these are the long, narrow enclosures known as cursus. These were followed by massive ditched and banked enclosures called henges and then smaller monuments, including round barrows. The A1 also passes by Iron Age settlements and Roman towns, forts and villas. This map shows the route of the A1 in Yorkshire and North of Boroughbridge the A1 the major prehistoric monuments that lie close by. follows Dere Street Roman road. Please be aware that the monuments featured in this booklet may lie on privately-owned land. 1 The Landscape Setting of the A1 Road Neolithic and Bronze Age Monuments Between Boroughbridge and Cursus monuments are very long larger fields A1 Road quarries Catterick the A1 heads north with rectangular enclosures, typically more the Pennines to the west and than 1km long. They are thought to the low lying vales of York and date from the middle to late Neolithic Mowbray to the east. This area period and were probably used for has a rural feel with a few larger ceremonies and rituals. settlements (like the cathedral city of Ripon and the market town of The western end of the Thornborough pockets of woodland cursus is rounded but some are square. -

(Electoral Changes) Order 2000

545297100128-09-00 23:35:58 Pag Table: STATIN PPSysB Unit: PAG1 STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2000 No. 2600 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The District of Hambleton (Electoral Changes) Order 2000 Made ----- 22nd September 2000 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) Whereas the Local Government Commission for England, acting pursuant to section 15(4) of the Local Government Act 1992(a), has submitted to the Secretary of State a report dated November 1999 on its review of the district of Hambleton together with its recommendations: And whereas the Secretary of State has decided to give effect to those recommendations: Now, therefore, the Secretary of State, in exercise of the powers conferred on him by sections 17(b) and 26 of the Local Government Act 1992, and of all other powers enabling him in that behalf, hereby makes the following Order: Citation, commencement and interpretation 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the District of Hambleton (Electoral Changes) Order 2000. (2) This Order shall come into force— (a) for the purposes of proceedings preliminary or relating to any election to be held on 1st May 2003, on 10th October 2002; (b) for all other purposes, on 1st May 2003. (3) In this Order— “district” means the district of Hambleton; “existing”, in relation to a ward, means the ward as it exists on the date this Order is made; any reference to the map is a reference to the map prepared by the Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions marked “Map of the District of Hambleton (Electoral Changes) Order 2000”, and deposited in accordance with regulation 27 of the Local Government Changes for England Regulations 1994(c); and any reference to a numbered sheet is a reference to the sheet of the map which bears that number. -

Areas Designated As 'Rural' for Right to Buy Purposes

Areas designated as 'Rural' for right to buy purposes Region District Designated areas Date designated East Rutland the parishes of Ashwell, Ayston, Barleythorpe, Barrow, 17 March Midlands Barrowden, Beaumont Chase, Belton, Bisbrooke, Braunston, 2004 Brooke, Burley, Caldecott, Clipsham, Cottesmore, Edith SI 2004/418 Weston, Egleton, Empingham, Essendine, Exton, Glaston, Great Casterton, Greetham, Gunthorpe, Hambelton, Horn, Ketton, Langham, Leighfield, Little Casterton, Lyddington, Lyndon, Manton, Market Overton, Martinsthorpe, Morcott, Normanton, North Luffenham, Pickworth, Pilton, Preston, Ridlington, Ryhall, Seaton, South Luffenham, Stoke Dry, Stretton, Teigh, Thistleton, Thorpe by Water, Tickencote, Tinwell, Tixover, Wardley, Whissendine, Whitwell, Wing. East of North Norfolk the whole district, with the exception of the parishes of 15 February England Cromer, Fakenham, Holt, North Walsham and Sheringham 1982 SI 1982/21 East of Kings Lynn and the parishes of Anmer, Bagthorpe with Barmer, Barton 17 March England West Norfolk Bendish, Barwick, Bawsey, Bircham, Boughton, Brancaster, 2004 Burnham Market, Burnham Norton, Burnham Overy, SI 2004/418 Burnham Thorpe, Castle Acre, Castle Rising, Choseley, Clenchwarton, Congham, Crimplesham, Denver, Docking, Downham West, East Rudham, East Walton, East Winch, Emneth, Feltwell, Fincham, Flitcham cum Appleton, Fordham, Fring, Gayton, Great Massingham, Grimston, Harpley, Hilgay, Hillington, Hockwold-Cum-Wilton, Holme- Next-The-Sea, Houghton, Ingoldisthorpe, Leziate, Little Massingham, Marham, Marshland -

Snowden-Daulton Family History

~ 1 ~ SNOWDEN-DAULTON FAMILY HISTORY The Royal Irish 27th Inniskillings Left: Queens Colours Right: Regiment Colours ~ 2 ~ SNOWDEN FAMILY THREADS MY MUMS PEOPLE COMPILED BY ROGER MOLD CHAPTERS INTRODUCTION PAGE 4 1 THE SNOWDENS FROM YORKSHIRE PAGE 8 2 GEORGE AND DIANE SNOWDEN FROM YORKSHIRE TO RAMSGATE PAGE 46 3 GEORGE AND MARY SNOWDEN PAGE 59 4 THE SNOWDEN FAMILY TREE PAGE 62 5 DAULTON FAMILY PAGE 80 6 DAULTONS FAMILY TREE PAGE 90 ~ 3 ~ MUM -NANA THIS WAS YOUR LIFE SNOWDEN =DAULTON FAMILIES ABOVE: IN THIS PHOTO YOU WERE ABOUT NINETEEN YEARS OLD BORN: 2. JUNE. 1922. DIED: 8. JANUARY. 2003. (80 YEARS OLD) ~ 4 ~ INTRODUCTION Dear Mum (You suffered with a Bi-Polar disorder for most of your adult life) I have a great need to write down the deep feelings I have for the part my Mum played in shaping my life. As you read on you may question and you may criticize, but hopefully you will understand, they are my feelings only, please respect them. For a big part of her life my Mum had an illness disorder known as “Bi-polar or Manic depression” The illness tends to run in families and appears to have a genetic link in fact this illness is and was prevalent in the Daulton family. So now what are you thinking? Some of you will immediately say “oh gosh” I don’t want to know and put this away in the too hard file. Some of you will read on through curiosity and respect and then file it. But I sincerely hope some of you will show a genuine interest and will openly and with deep concern continue on with your learning of this illness. -

Topography of Great Britain Or, British Traveller's Pocket Directory : Being

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES TOPOGRAPHY OF iHteat Mvitai% tT' OR, BRITISH TRAVELLER'S POCKET DIRECTORY; BEIN& AN ACCDRATE AND COMPREHENSIVE TOPOGRAPHICAL AND STATISTICAL DESCRIPTION OF ALL THE COUNTIES IN WITH THE ADJACENT ISLANDS: ILLUSTRATED WITH MAPS OF THE COUNTIES, WHICH FORM A COMPLETE BRITISH ATLAS. BY G. A. COOKE, ESQ. VOL. XXL CONTAININ& YORKSHIRE. Printed, by Assignment from the Executors of the late C. Cooke, FOR SHERWOOD, NEELY, AND JONES, PATERNOSTER-ROWj; AND SOLD BY ALL UOOKSELLERS. TOPOGRAPHICAL AND STATISTICAL DESCRIPTION OF THE COUNTY OF YORK; Containing an Account of its Situation, li. M'Millan, Printer. Bow-Street, Covent-Gavdcn. C3) A Ti^ABLE OF THE PRINCIPAL TOWNS IN THE S2!le3t KiDittg of pork$i}ire; Their Distance from London, Markets, Houses, and Inhabitants r=^ with the Time of the Arrival and Departure of the Post. Towns. Dist. Markets. Houses, Inhabi- Post tants. amves. Aberford 186 Wed. 176 922 Barnsley 176 Wed. 954 5014 12| m. Bawtry 153 Wed. 178 918 4f aft. Bingley 206 Tuesd. 931 4782 7 m. Boroughbridge 206 Sat. 131 747 llf m. Bradford 196 Thurs. 548 2989 5im. Dent 266 Friday. 379 1663 Dewsbury 187 Wed. 987 5509 Doncaster 162 Sat. 1438 6935 6 aft. Gisburn 224 Monday, 100 509 Halifax 197 Sat. 501 £677 41 m. Huddersfield . 189 Tuesd. 1871 9671 3im. Keighley 209 Wed. 1367 6864 84 ra. Kettlewell 233 Thurs. 125 361 Knaresborough 202 Wed. 888 4234 7 m. Leeds ... ., 193 Tu. Sat. 12,240 62,534 3|m. Otley 205 Friday. 530 2602 Pontefract 177 Sat. -

Subsidence Hazards Caused by the Dissolution of Permian Gypsum in England: Geology, Investigation and Remediation

SUBSIDENCE HAZARDS CAUSED BY THE DISSOLUTION OF PERMIAN GYPSUM IN ENGLAND: GEOLOGY, INVESTIGATION AND REMEDIATION A H Cooper, British Geological Survey, Kingsley Dunham Centre, Keyworth, Nottingham NG12 5GG. This is a recompiled version of the final draft of the published paper, it is presented with coloured versions of the figures and may differ slighly from the published edited version. Please respect copyright of BGS/NERC and refer to the final published version if you wish to quote the work. Published as: Cooper, AH. 1998. Subsidence hazards caused by the dissolution of Permian gypsum in England: geology, investigation and remediation. 265–275 in: Geohazards in engineering geology, Maund, JG, Eddleston, M (eds.). Geological Society of London. Special Publications in Engineering Geology, 15. ABSTRACT About every three years natural catastrophic subsidence, caused by gypsum dissolution, occurs in the vicinity of Ripon, North Yorkshire, England. Holes up to 35 m across and 20 m deep have appeared without warning. In the past 150 years, 30 major collapses have occurred, and in the last ten years the resulting damage to property is estimated at about £1,000,000. Subsidence, associated with the collapse of caves resulting from gypsum dissolution in the Permian rocks of eastern England, occurs in a belt about 3 km wide and over 100 km long. Gypsum (CaSO4.2H2O) dissolves rapidly in flowing water and the cave systems responsible for the subsidence are constantly enlarging, causing a continuing subsidence problem. Difficult ground conditions are associated with caves, subsidence breccia pipes (collapsed areas of brecciated and foundered material), crown holes and post-subsidence fill deposits. -

2000 No. 2601 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The

0 R STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2000 No. 2601 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The Borough of Harrogate (Electoral Changes) Order 2000 Made---- 22nd September 2000 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) to (4) Whereas the Local Government Commission for England, acting pursuant to section 15(4) of the Local Government Act 1992(a), has submitted to the Secretary of State a report dated November 1999 on its review of the borough(b) of Harrogate together with its recommendations: And whereas the Secretary of State has decided to give effect, subject to one modification, to those recommendations: Now, therefore, the Secretary of State, in exercise of the powers conferred on him by sections 17(c) and 26 of the Local Government Act 1992, and of all other powers enabling him in that behalf, hereby makes the following Order: Citation, commencement and interpretation 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the Borough of Harrogate (Electoral Changes) Order 2000. (2) This article and articles 2, 3, 9 and 10 shall come into force— (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary or relating to any election to be held on 2nd May 2002, on 10th October 2001; (b) for all other purposes, on 2nd May 2002. (3) Articles 4, 5 and 8 of this Order shall come into force— (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary or relating to the election of parish councillors for the parishes of Boroughbridge, Killinghall and Whixley, respectively, to be held on 6th May 2004, on 10th October 2003. (b) for all other purposes, on 6th May 2004. -

The Scropfs of Bolton and of Masham

THE SCROPFS OF BOLTON AND OF MASHAM, C. 1300 - C. 1450: A STUDY OF A kORTHERN NOBLE FAMILY WITH A CALENDAR OF THE SCROPE OF BOLTON CARTULARY 'IWO VOLUMES VOLUME II BRIGh h VALE D. PHIL. THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY MAY 1987 VOLUME 'IWO GUIDE '10 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION CALENDAR OF THE SCROPE OF BOLTON CARTULARY 1 GUIDE '10 Call'ENTS page 1. West Bolton 1 2. Little Bolton or Low Bolton 7, 263 3. East Bolton or Castle Bolton 11, 264 4. Preston Under Scar 16, 266 5. Redmire 20, 265, 271 6. Wensley 24, 272 7. Leyburn 38, 273 8. Harmby 43, 274, 276 9. Bellerby 48, 275, 277 10. Stainton 57, 157 11. Downholme 58, 160 12. Marske 68, 159 13. Richmond 70, 120, 161 14. Newton Morrell 79, 173 15. rolby 80, 175 16. Croft on Tees 81, 174 17. Walmire 85 18. Uckerby 86, 176 19. Bolton on Swale 89, 177 20. Ellerton on Swale 92, 178, 228, 230 21. Thrintoft 102, 229 22. Yafforth 103, 231 23. Ainderby Steeple 106, 232 24. Caldwell 108, 140, 169 25. Stanwick St. John 111, 167 26. Cliff on Tees 112 27. Eppleby 113, 170 28. Aldbrough 114, 165 29. Manfield 115, 166 30. Brettanby and Barton 116, 172 31. Advowson of St. Agatha's, Easby 122, 162 32. Skeeby 127, 155, 164 33. Brampton on Swale 129, 154 34. Brignall 131, 187 35. Mbrtham 137, 186 36. Wycliffe 139, 168 37. Sutton Howgrave 146, 245 38. Thornton Steward 150, 207 39. Newbiggin 179, 227 40. -

Download: Open Space, Sport And

Hambleton District Council Open Space, Sport and Recreation Study Appendices August 2006 CONTENTS Page Appendix A – Benefits of Open Space 1 Appendix B – Household Survey and Covering letter 5 Appendix C – Site Audit by Analysis Area 13 Appendix C a – Site Audit by Typology 31 Appendix D – Site Assessments Definitions and Matrix 46 Appendix E – Quality Standards 53 Appendix F – Quality Standards 67 Appendix G – Accessibility Standards 80 Appendix H – Quantity Standards Worksheet 93 Appendix I – National Strategic Context 96 Appendix J – Quality Benchmarking 107 Prepared by PMP 3 Brunel Court Gadbrooke Park Northwich Cheshire CW9 7LP APPENDIX A BENEFITS OF OPEN SPACE 1 2 BENEFITS OF OPEN SPACE – APPENDIX A Wider Benefits of Open Space • providing safe outdoor areas that are available to all ages of the local population to mix and socialise • social cohesion - potential to engender a sense of Social community ownership and pride • providing opportunities for community events, voluntary activities and charitable fund raising • providing opportunities to improve health and take part in a wide range of outdoor sports and activities. • providing easily accessible recreation areas as an alternative to other more chargeable leisure pursuits • offers wide range of leisure opportunities from informal Recreational leisure and play to formal events, activities and games. • open spaces, particularly parks, are the first areas where children come into contact with the natural world • play opportunities are a vital factor in the development of children. • reducing motor car dependence to access specific facilities • providing habitats for wildlife as an aid to local biodiversity • helping to stabilise urban temperatures and humidity Environmental • providing opportunities for the recycling of organic materials • providing opportunities to reduce transport use through the provision of local facilities. -

Vale of York, Kirby Hill and Hutton Conyers MSA Inquiry

_________________________________________________________________________ Town and Country Planning Act 1990 – Section 78 Appeal Appeal by Moto Hospitality Limited Land Comprising Field at 435074 475842, Hutton Conyers, North Yorkshire Against the Refusal of Planning Permission by Harrogate Borough Council on the Outline Application for: “Construction of new Motorway Service Area ("MSA") to comprise: amenity building, lodge, drive thru coffee unit, associated car, coach, motorcycle, caravan, HGV and abnormal load parking and a fuel filling station with retail shop, together with alterations to the adjacent roundabout at Junction 50 of the A1(M) to form an access point and works to the local highway network. Provision of landscaping, infrastructure and ancillary works.” Application Reference: 18/02713/EIAMAJ Appeal Reference: APP/E2734/W/20/3261729 Proof of Evidence AFR Collins – January 2021 AFR COLLINS MRICS MRTPI MCIT MILT MEWI T 01376 538533 Collins & Coward Ltd M 07825 633573 The Courtyard F 01376 563240 9A East Street E [email protected] Coggeshall W www.collinscoward.co.uk Essex CO6 1SH _________________________________________________________ Motorway Service Area Junction 50 of A1(M) Proof of Evidence of AFR Collins Moto Hospitality Ltd Collins & Coward Ltd __________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS 1 PERSONAL INTRODUCTION AND SCOPE OF EVIDENCE 2 INTRODUCTION 3 THE SITE AND SURROUNDING AREA 4 THE PLANNING HISTORY & ENGAGEMENT (i) Planning History (II) Pre-Application -

Prospect Gardens, Sutton Howgrave, Bedale, North Yorkshire, DL8 2NS

Prospect Gardens, Sutton Howgrave, Bedale, North Yorkshire, DL8 2NS Guide price £449,950 www.joplings.com A substantial THREE BEDROOM, DETACHED BUNGALOW occupying a private position on the edge of this attractive residential village. Sutton Howgrave is conveniently set between three market towns being only 9 miles from Thirsk or Bedale or 7 miles from Ripon. The property benefits from flexible living accommodation, set in approximately a THIRD OF AN ACRE OF GARDENS with PARKING for numerous vehicles and an attached DOUBLE GARAGE. www.joplings.com DIRECTIONS Integrated Double Oven and Grill. Electric Ceramic OUTSIDE Ripon - From the Ripon Bypass proceed up Hutton Hob. Integrated Deep Fat Fryer. Space and plumbing Wooden Shed and Oil Tank at the Rear. Gravel in Bank and turn left to Hutton Conyers. Proceed for Dishwasher and Washing Machine. Tiled and out Driveway to the Front. Two Wrought Iron through the village and continue on to Wath. On splashback. Recessed lighting. TV Point. BT Point. Gates. Hedged boundaries. Open Views. entering Wath take the second turning on the left to Radiator. UPVC Double Glazed opaque part glazed Sutton Howgrave. Continue to the village and the door to Garden. GARDENS property will be the first house you come to on your Gardens to all sides, laid mainly to lawn with mature left hand side. MASTER BEDROOM 12'8"max x 13' (3.86m shrubs and trees. x 3.96m) ENTRANCE UPVC Double Glazed Window to the Rear. Built in DOUBLE GARAGE 25' X 18' (7.62m X 5.49m) UPVC Georgian style Double Glazed door with wardrobes, cupboards and dressing table.