Cameroon's Unfolding Catastrophe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Africanprogramme for Onchocerctasts Control (Apoc)

RESERVED FOR PROTECT LOGO/HEADING COUNTRYAIOTF: CAMEROON Proiect Name: CDTI SW 2 Approval vearz 1999 Launchins vegr: 2000 Renortins Period: From: JANUARY 2008 To: DECEMBER 2008 (Month/Year) ( Mont!{eq) Proiectvearofthisrenort: (circleone) I 2 3 4 5 6 7(8) 9 l0 Date submitted: NGDO qartner: "l"""uivFzoog Sightsavers International South West 2 CDTI Project Report 2008 - Year 8. ANNUAL PROJECT TECHNICAL REPORT SUBMITTED TO TECHNICAL CONSULTATTVE COMMITTEE (TCC) DEADLINE FOR SUBMISSION: To APOC Management by 3l January for March TCC meeting To APOC Management by 31 Julv for September TCC meeting AFRICANPROGRAMME FOR ONCHOCERCTASTS CONTROL (APOC) I I RECU LE I S F[,;, ?ur], APOC iDIR ANNUAL I'II().I Ii(]'I"IIICHNICAL REPORT 't'o TECHNICAL CONSU l.',l'A]'tvE CoMMITTEE (TCC) ENDORSEMENT Please confirm you have read this report by signing in the appropriat space. OFFICERS to sign the rePort: Country: CAMEROON National Coordinator Name: Dr. Ntep Marcelline S l) u b Date: . ..?:.+/ c Ail 9ou R Regional Delegate Name: Dr. Chu + C( z z a tu Signature: n rJ ( Date 6t @ RY oF I DE LA NGDO Representative Name: Dr. Oye Joseph E Signature: .... Date:' g 2 JAN. u0g Regional Oncho Coordinator Name: Mr. Ebongo Signature: Date: 51-.12-Z This report has been prepared by Name : Mr. Ebongo Peter Designation:.OPC SWII Signature: *1.- ,l 1l Table of contents Acronyms .v Definitions vi FOLLOW UP ON TCC RECOMMENDATIONS. 7 Executive Summary.. 8 SECTION I : Background information......... 9 1.1. GrrueRruINFoRMATroN.................... 9 1.1.1 Description of the project...... 9 Location..... 9 1. 1. 2. -

Re Joinder Submitted by the Republic of Uganda

INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE CASE CONCERNING ARMED ACTIVITIES ON THE TERRITORY OF THE CONGO DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO v. UGANDA REJOINDER SUBMITTED BY THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA VOLUME 1 6 DECEMBER 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION .................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1 : THE PERSISTENT ANOMALIES IN THE REPLY CONCERNING MATTERS OF PROCEDURE AND EVIDENCE ............................................... 10 A. The Continuing Confusion Relating To Liability (Merits) And Quantum (Compensation) ...................... 10 B. Uganda Reaffirms Her Position That The Court Lacks Coinpetence To Deal With The Events In Kisangani In June 2000 ................................................ 1 1 C. The Courl:'~Finding On The Third Counter-Claim ..... 13 D. The Alleged Admissions By Uganda ........................... 15 E. The Appropriate Standard Of Proof ............................. 15 CHAPTER II: REAFFIRMATION OF UGANDA'S NECESSITY TO ACT IN SELF- DEFENCE ................................................. 2 1 A. The DRC's Admissions Regarding The Threat To Uganda's Security Posed By The ADF ........................ 27 B. The DRC's Admissions Regarding The Threat To Uganda's Security Posed By Sudan ............................. 35 C. The DRC's Admissions Regarding Her Consent To The Presetnce Of Ugandan Troops In Congolese Territory To Address The Threats To Uganda's Security.. ......................................................................4 1 D. The DRC's Failure To Establish That Uganda Intervened -

Understanding African Armies

REPORT Nº 27 — April 2016 Understanding African armies RAPPORTEURS David Chuter Florence Gaub WITH CONTRIBUTIONS FROM Taynja Abdel Baghy, Aline Leboeuf, José Luengo-Cabrera, Jérôme Spinoza Reports European Union Institute for Security Studies EU Institute for Security Studies 100, avenue de Suffren 75015 Paris http://www.iss.europa.eu Director: Antonio Missiroli © EU Institute for Security Studies, 2016. Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, save where otherwise stated. Print ISBN 978-92-9198-482-4 ISSN 1830-9747 doi:10.2815/97283 QN-AF-16-003-EN-C PDF ISBN 978-92-9198-483-1 ISSN 2363-264X doi:10.2815/088701 QN-AF-16-003-EN-N Published by the EU Institute for Security Studies and printed in France by Jouve. Graphic design by Metropolis, Lisbon. Maps: Léonie Schlosser; António Dias (Metropolis). Cover photograph: Kenyan army soldier Nicholas Munyanya. Credit: Ben Curtis/AP/SIPA CONTENTS Foreword 5 Antonio Missiroli I. Introduction: history and origins 9 II. The business of war: capacities and conflicts 15 III. The business of politics: coups and people 25 IV. Current and future challenges 37 V. Food for thought 41 Annexes 45 Tables 46 List of references 65 Abbreviations 69 Notes on the contributors 71 ISSReportNo.27 List of maps Figure 1: Peace missions in Africa 8 Figure 2: Independence of African States 11 Figure 3: Overview of countries and their armed forces 14 Figure 4: A history of external influences in Africa 17 Figure 5: Armed conflicts involving African armies 20 Figure 6: Global peace index 22 Figure -

Status of Lgbti People in Cameroon, Gambia, Ghana and Uganda

STATUS OF LGBTI PEOPLE IN CAMEROON, GAMBIA, GHANA AND UGANDA 3.12.2015 Finnish Immigration Service Country Information Service Public Theme Report 1 (123) Table of contents Disclaimer .................................................................................................................................................... 3 List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................... 4 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 7 1.1. The colonial legacy of anti-sodomy laws ......................................................................................... 7 1.2. The significance of current laws criminalising same-sex conduct ............................................. 11 1.3. Particularities of the situation of lesbians and bisexual women................................................. 12 1.4. Particularities of the situation of transgender and intersex people ........................................... 14 1.5. Violations of international and regional human rights law .......................................................... 14 2. Cameroon .............................................................................................................................................. 18 2.1. The legal framework ........................................................................................................................ -

Dictionnaire Des Villages Du Fako : Village Dictionary of Fako Division

OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIOUE ET TECHNIOUE OUTRE· MER Il REPUBLIQUE UNIE DU CAMEROUN DICTIONNAIRE DES VILLAGES DU FAKO VILLAGE DICTIONARY OF FAKO DIVISION SECTION DE GEOGRAPHIE 1 OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE SCIm~TIFIQUE REPUBLIQUE UNIE ET TECmUQUE OUTRE-lViER DU CAlvŒROUN UNITED REPUBLIC OF CANEROON CENTRE O.R.S.T.O.N DE YAOUNDE DICTIONNAIRE DES VILLAGES DU FAKO VILLAGE DICTIONARY OF FAKO DIVISION Juillet 1973 July 1973 COPYRIGHT O.R.S.T.O.M 1973 TABLE DES NATIERES CONTENTS i l j l ! :i i ~ Présentation •••••.•.•.....••....•.....•....••••••.••.••••••.. 1 j Introduction ........................................•• 3 '! ) Signification des principaux termes utilisés •.............• 5 î l\lIeaning of the main words used Tableau de la population du département •...••.....•..•.•••• 8 Population of Fako division Département du Fako : éléments de démographie •.•.... ..••.•• 9 Fako division: demographic materials Arrondissements de Muyuka et de Tiko : éléments de . démographie 0 ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 10 11uyul{a and Tileo sl)..bdivisions:demographic materials Arrondissement de Victoria: éléments de démographie •••.••• 11 Victoria subdivision:demographic materials Les plantations (12/1972) •••••••••••.•••••••••••••••••••••• 12 Plantations (12/1972) Liste des villages par arrondissement, commune et graupement 14 List of villages by subdivision, area council and customary court Signification du code chiffré •..•••...•.•...•.......•.•••.• 18 Neaning of the code number Liste alphabétique des villages ••••••.••••••••.•.•..•••.•.• 19 -

Shelter Cluster Dashboard NWSW052021

Shelter Cluster NW/SW Cameroon Key Figures Individuals Partners Subdivisions Cameroon 03 23,143 assisted 05 Individual Reached Trend Nigeria Furu Awa Ako Misaje Fungom DONGA MANTUNG MENCHUM Nkambe Bum NORD-OUEST Menchum Nwa Valley Wum Ndu Fundong Noni 11% BOYO Nkum Bafut Njinikom Oku Kumbo Belo BUI Mbven of yearly Target Njikwa Akwaya Jakiri MEZAM Babessi Tubah Reached MOMO Mbeggwi Ngie Bamenda 2 Bamenda 3 Ndop Widikum Bamenda 1 Menka NGO KETUNJIA Bali Balikumbat MANYU Santa Batibo Wabane Eyumodjock Upper Bayang LEBIALEM Mamfé Alou OUEST Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Fontem Nguti KOUPÉ HNO/HRP 2021 (NW/SW Regions) Toko MANENGOUBA Bangem Mundemba SUD-OUEST NDIAN Konye Tombel 1,351,318 Isangele Dikome value Kumba 2 Ekondo Titi Kombo Kombo PEOPLE OF CONCERN Abedimo Etindi MEME Number of PoC Reached per Subdivision Idabato Kumba 1 Bamuso 1 - 100 Kumba 3 101 - 2,000 LITTORAL 2,001 - 13,000 785,091 Mbongé Muyuka PEOPLE IN NEED West Coast Buéa FAKO Tiko Limbé 2 Limbé 1 221,642 Limbé 3 [ Kilometers PEOPLE TARGETED 0 15 30 *Note : Sources: HNO 2021 PiN includes IDP, Returnees and Host Communi�es The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Key Achievement Indicators PoC Reached - AGD Breakdouwn 296 # of Households assisted with Children 27% 26% emergency shelter 1,480 Adults 21% 22% # of households assisted with core 3,769 Elderly 2% 2% relief items including prevention of COVID-19 21,618 female male 41 # of households assisted with cash for rental subsidies 41 Households Reached Individuals Reached Cartegories of beneficiaries reported People Reached by region Distribution of Shelter NFI kits integrated with COVID 19 KITS in Matoh town. -

The Anglophone Cameroon Crisis: by Jon Lunn and Louisa Brooke-Holland April 2019 Update

BRIEFING PAPER Number 8331, 17 April 2019 The Anglophone Cameroon crisis: By Jon Lunn and Louisa April 2019 update Brooke-Holland Contents: 1. Overview 2. History and its legacies 3. 2015-17: main developments 4. 2018: main developments 5. Events during 2019 and future prospects 6. Response of Western governments and the UN www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 The Anglophone Cameroon crisis: April 2019 update Contents Summary 3 1. History and its legacies 5 2. 2015-17: main developments 8 3. 2018: main developments 10 4. Events during 2019 and future prospects 12 5. Response of Western governments and the UN 13 Cover page image copyright: Image 5584098178_709d889580_o – Welcome signs to Santa, gateway to the anglophone Northwest Region, Cameroon, March 2011 by Joel Abroad – Flickr.com page. Licensed by Attribution-Non Commercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)/ image cropped. 3 Commons Library Briefing, 17 April 2019 Summary Relations between the two Anglophone regions of Cameroon and the country’s dominant Francophone elite have long been fraught. Over the past three years, tensions have escalated seriously and since October 2017 violent conflict has erupted between armed separatist groups and the security forces, with both sides being accused of committing human rights abuses. The tensions originate in a complex and contested decolonisation process in the late-1950s and early-1960s, in which Britain, as one of the colonial powers, was heavily involved. Federal arrangements were scrapped in 1972 by a Francophone- dominated central government. Many English-speaking Cameroonians have long complained that they are politically, economically and linguistically marginalised. -

CASE STUDY CAMEROON THESIS Aw

T.C. ISTANBUL AYDIN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES INVESTIGATION ON CAUSES OF CIVIL WAR: CASE STUDY CAMEROON THESIS Awo EPEY P. Department of Political Science and International Relations Political Science and International Relations Program Thesis Advisor: Assist. Prof. Dr. Özüm Sezin UZUN June, 2019 T.C. ISTANBUL AYDIN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES INVESTIGATION ON CAUSES OF CIVIL WAR: CASE STUDY CAMEROON M. Sc. THESIS Awo EPEY P. (Y1812.110032) Department of Political Science and International Relations Political Science and International Relations Program Thesis Advisor: Assist. Prof. Dr. Özüm Sezin UZUN June, 2019 DEDICATION This work is specially dedicated to my lovely late mother Mami Dorothy Ngkanghe who had always wish to see me climb the academic ladder, and to my dear wife Violet Etona Rokende, my lovely kids Awo Dunia Rouge Nkanghe, Awo Mabel Rouge Oben, and my late junior brother Epey Cyprian Oben, for their constant moral supports. ii FOREWORD Glory to God Almighty who has made this piece of work possible. Except the Lord builds for his people, the builder builds in vain. My deepest appreciation goes to my Supervisor Assist. Prof. Dr. Özüm Sezin UZUN for her effort to the success of this work. “Thank you Doctor” is the supreme statement I can use to express my gratitude. Special thanks goes to my lecturers who directly or indirectly helped me out in this work; Dr.Egemen BAGIS, Prof. Hatice Deniz YUKSEKER, Assist. Prof. Dr. Özüm Sezin UZUN, Dr. Filiz KATMAN, Dr Gökhan DUMAN and all other lecturers in Istanbul Aydin University whose class lectures were very instrumental in the realization of this work. -

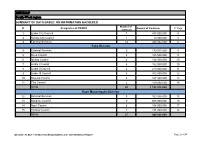

MINMAP South-West Region

MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts 1 Limbe City Council 7 475 000 000 4 2 Kumba City Council 1 10 000 000 5 3 External Services 14 440 032 000 6 Fako Division 4 External Services 9 179 015 000 8 5 Buea Council 5 125 500 000 9 6 Idenau Council 4 124 000 000 10 7 Limbe I Council 4 152 000 000 10 8 Limbe II Council 4 219 000 000 11 9 Limbe III Council 6 102 500 000 12 10 Muyuka Council 6 127 000 000 13 11 Tiko Council 5 159 000 000 14 TOTAL 43 1 188 015 000 Kupe Muanenguba Division 12 External Services 5 100 036 000 15 13 Bangem Council 9 605 000 000 15 14 Nguti Council 6 104 000 000 17 15 Tombel Council 7 131 000 000 18 TOTAL 27 940 036 000 MINMAP / PUBLIC CONTRACTS PROGRAMMING AND MONITORING DIVISION Page 1 of 34 MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Lebialem Division 16 External Services 5 134 567 000 19 17 Alou Council 9 144 000 000 19 18 Menji Council 3 181 000 000 20 19 Wabane Council 9 168 611 000 21 TOTAL 26 628 178 000 Manyu Division 18 External Services 5 98 141 000 22 19 Akwaya Council 6 119 500 000 22 20 Eyomojock Council 6 119 000 000 23 21 Mamfe Council 5 232 000 000 24 22 Tinto Council 6 108 000 000 25 TOTAL 28 676 641 000 Meme Division 22 External Services 5 85 600 000 26 23 Mbonge Council 7 149 000 000 26 24 Konye Council 1 27 000 000 27 25 Kumba I Council 3 65 000 000 27 26 Kumba II Council 5 83 000 000 28 27 Kumba III Council 3 84 000 000 28 TOTAL 24 493 600 000 MINMAP / PUBLIC CONTRACTS -

Country Travel Risk Summaries

COUNTRY RISK SUMMARIES Powered by FocusPoint International, Inc. Report for Week Ending September 19, 2021 Latest Updates: Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, India, Israel, Mali, Mexico, Myanmar, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Turkey, Ukraine and Yemen. ▪ Afghanistan: On September 14, thousands held a protest in Kandahar during afternoon hours local time to denounce a Taliban decision to evict residents in Firqa area. No further details were immediately available. ▪ Burkina Faso: On September 13, at least four people were killed and several others ijured after suspected Islamist militants ambushed a gendarme patrol escorting mining workers between Sakoani and Matiacoali in Est Region. Several gendarmes were missing following the attack. ▪ Cameroon: On September 14, at least seven soldiers were killed in clashes with separatist fighters in kikaikelaki, Northwest region. Another two soldiers were killed in an ambush in Chounghi on September 11. ▪ India: On September 16, at least six people were killed, including one each in Kendrapara and Subarnapur districts, and around 20,522 others evacuated, while 7,500 houses were damaged across Odisha state over the last three days, due to floods triggered by heavy rainfall. Disaster teams were sent to Balasore, Bhadrak and Kendrapara districts. Further floods were expected along the Mahanadi River and its tributaries. ▪ Israel: On September 13, at least two people were injured after being stabbed near Jerusalem Central Bus Station during afternoon hours local time. No further details were immediately available, but the assailant was shot dead by security forces. ▪ Mali: On September 13, at least five government soldiers and three Islamist militants were killed in clashes near Manidje in Kolongo commune, Macina cercle, Segou region, during morning hours local time. -

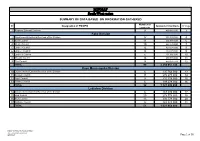

MINMAP South-West Region

MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts 1 Regional External Services 9 490 982 000 3 Fako Division 2 Départemental External Services of the Division 17 352 391 000 4 3 Buea Council 11 204 778 000 6 4 Idenau Council 10 224 778 000 7 5 Limbe I Council 12 303 778 000 8 6 Limbe II Council 13 299 279 000 9 7 Limbe III Council 6 151 900 000 10 8 Muyuka Council 16 250 778 000 11 9 Tiko Council 14 450 375 748 12 TOTAL 99 2 238 057 748 Kupe Muanenguba Division 10 Départemental External Services of the Division 6 135 764 000 13 11 Bangem Council 11 572 278 000 14 12 Nguti Council 9 215 278 000 15 13 Tombel Council 6 198 278 000 16 TOTAL 32 1 121 598 000 Lebialem Division 14 Départemental External Services of the Division 6 167 474 000 17 15 Alou Council 20 278 778 000 18 16 Menji Council 13 306 778 000 20 17 Wabane Council 12 268 928 000 21 TOTAL 51 1 021 958 000 PUBLIC CONTRACTS PROGRAMMING AND MONITORING DIVISION /MINMAP Page 1 of 36 MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts Manyu Division 18 Départemental External Services of the Division 9 240 324 000 22 19 Akwaya Council 10 260 278 000 23 20 Eyumojock Council 6 195 778 000 24 21 Mamfe Council 7 271 103 000 24 22 Tinto Council 7 219 778 000 25 TOTAL 39 1 187 261 000 Meme Division 23 Départemental External Services of the Division 4 82 000 000 26 24 Konye Council 5 171 533 000 26 25 Kumba -

“Investigating the Causes of Civil Wars in Sub-Saharan Africa” Case Study: the Central African Republic and South Sudan

al Science tic & li P o u P b f l i o c l A a f Journal of Political Sciences & Public n f r a u i r o s J ISSN: 2332-0761 Affairs Review Article “Investigating the Causes of Civil Wars in Sub-Saharan Africa” Case Study: The Central African Republic and South Sudan Agberndifor Evaristus Department Political Science and International Relations, Istanbul Aydin University, Istanbul, Turkey ABSTRACT Civil wars are not new and they predate the modern nation states. From the time when nations gathered in well- defined or near defined geographical locations, there has always been internal wrangling between the citizens and the state for reasons that might not be very different from place to place. However, the tensions have always mounted up such that people took to the streets first to protest and sometimes, the immaturity of the government to listen to the demands of the people radicalized them for bloodshed. This paper shall empirically examine the cause of civil wars in Sub-Saharan Africa having at the back of its thoughts that civil wars are most times associated to political, economic and ethnic incentives. This paper shall try in empirical terms using data from already established research to prove these points. Firstly, it shall explain its independent variables which apparently are some underlying causes of civil wars. Secondly, it shall consider the dense literature review of civil wars and shall look at some definitions, theories of civil wars and data presented on a series of countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Lastly, it shall isolate two countries that will make up its comparative analysis and the explanations of its dependent variable by which it shall seek to understand what caused the outbreaks of civil wars in those two countries.