First World War – Recent Publications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Secrets and Spies Late at Churchill War Rooms Friday 4 October 2013 6.30Pm – 9.30Pm

Immediate release Secrets and Spies at Churchill War Rooms From September 2013, a series of secret and spy-themed events will take place beneath the streets of Whitehall, in Churchill’s secret underground bunker. These events include a lecture from Simon Pearson on his book The Great Escaper, following the sold out lecture by historian, Clare Mulley’s talk on her new book The Spy Who Loved and an espionage themed late night opening. Secrets and Spies Late at Churchill War Rooms Friday 4 October 2013 6.30pm – 9.30pm Churchill War Rooms will present London’s most unique night out this autumn. Experience Churchill War Rooms as never before, step back in time to a world of 1940s espionage and embark on a secret mission to discover if you have what it takes to reach the standard of a Special Operations Executive (SOE) under Churchill’s government. Take part in a spy challenge, decode hidden devices against the clock and seek out spy bugs planted around the site, using GPS devices. Encounter a SOE agent reenacting some of the most famous secret missions of Second World War and watch an official SOE recruitment film from IWM’s archives. In the spirit of the era, there will be 1940s themed drinks and those who complete the spy challenge will be entered into a draw to win a spy-themed weekend away and a private tour of Churchill War Rooms. 1940s vintage attire encouraged. Tickets: Adults, £17 Concessions, £13.60 Simon Pearson - The Great Escaper Tuesday 15 October 2013 7pm – 9pm (Doors open 6.30pm) Author and Times journalist Simon Pearson will discuss the extraordinary story of Roger Bushell, known as Big X, a prisoner of war noted for masterminding the ‘Great Escape’ at the infamous Stalag Luft III camp. -

Retribution: the Battle for Japan, 1944-45 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

RETRIBUTION: THE BATTLE FOR JAPAN, 1944-45 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Sir Max Hastings | 615 pages | 10 Mar 2009 | Random House USA Inc | 9780307275363 | English | New York, United States Retribution: The Battle for Japan, 1944-45 PDF Book One is the honest and detailed description of Japanese brutality. It invaded colonial outposts which Westerners had dominated for generations, taking absolutely for granted their racial and cultural superiority over their Asian subjects. The book greatly improved my limited knowledge of many of the key figures of the war in the Far East , particularly Macarthur, Chiang Kai Shek and one of the great forgotten British heroes, Bill Slim. The book is amazingly detailed in regards to the battles and the detail and clarity of each element brings into sharp focus the depth of human suffering and courage that so many people went through in this area. He gives one of the best accounts of the Soviet campaign in China and the Kuriles that I have found - given that it is only a section of the book and not a book in and of itself. The US were very reluctant for the Colonial Powers to take up their former territories after the War, to the extent that they refused to help the French in Indo-China, while Britain and Australia for differing reasons were critical of the US efforts to sideline their input to Japan's defeat. It was wildly fanciful to suppose that the consequences of military failure might be mitigated through diplomatic parley. He has presented historical documentaries for television, including series on the Korean War and on Churchill and his generals. -

Winston Churchill's Rhetoric and the Second World War Written By

Indiana University South Bend Undergraduate Research Journal Keep Calm and Carry On: Winston Churchill's Rhetoric and the Second World War Written by Abraham Maldonado-Orellana Edited by Chloe Lawrence "Of all the talents bestowed upon men, none is so The First World War, having ended in 1918, left instability in its precious as the gift oforatory ... Abandoned by his wake; the world had changed politically and culturally, only to be party betrayed by his friends, stripped of his offices, followed by a global economic depression in the 1930s. Memories of the Great War still resonated in people's minds. Fresh fears of whoever can command this power is still invasion set in as Britain heard the news of Poland's invasion by 1 formidable. " Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union on September 1, 1939. In 1940, the war became very real for the British and it would soon -Winston S. Churchill, 1897 become a pivotal year for the country's new Prime Minister. The Abstract: Battle of France, the evacuation at Dunkirk, The Battle of Britain and Churchill's most famous speeches all occurred during 1940, This article examines Prime Minister Winston Churchill's which one might call "the year of Churchill." role in creating a sense of national solidarity in wartime Britain and establishing an Anglocentric interpretation of World War II Churchill as Orator through his wartime speeches and publications. Churchill's Winston Churchill, a Conservative politician and Member of speeches and addresses during 1940 as well as his memoirs Parliament since 1900, would serve as Prime Minister of Great released after the war were heard and read by an international Britain during the Second World War. -

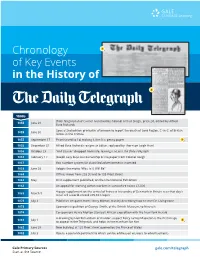

Chronology of Key Events in the History of the Daily Telegraph

Chronology 1 of Key Events in the History of 2 1800s Daily Telegraph And Courier launched by Colonel Arthur Sleigh, price 2d, edited by Alfred 1855 June 29 Bate Richards Special 2nd edition printed in afternoon to report the death of Lord Raglan, C.-in-C. of British 1855 June 30 forces in the Crimea 1855 September 17 Price halved to 1d, making it the first penny paper 1 1855 December 31 Alfred Bate Richards resigns as Editor, replaced by Thornton Leigh Hunt 1856 October 28 “And Courier” dropped from title, leaving it as just The Daily Telegraph 1857 February 17 Joseph Levy buys out ownership of the paper from Colonel Sleigh 1857 Box number system for classified advertisements invented 1858 June 25 Adopts the motto “Was, Is & Will Be” 1860 Offices move from 253 Strand to 135 Fleet Street 1861 May First supplement published, on the International Exhibition 1862 An appeal for starving cotton workers in Lancashire raises £6,000 4-page supplement on the arrival of Princess Alexandra of Denmark in Britain sees that day’s 1863 March 9 issue sell a world-record 205,884 copies 1872 July 3 Publishes despatch from Henry Morton Stanley describing how he met Dr. Livingstone 1873 Sponsors expedition of George Smith, of the British Museum, to Nineveh 1874 Co-sponsors Henry Morton Stanley’s African expedition with the New York Herald A drawing by Hall Richardson of murder suspect Percy Lefroy Mapleton is the first image 1881 July 1 2 to appear in the Telegraph, and helps in the manhunt for him 1882 June 28 New building at 135 Fleet Street opened by the Prince of Wales 1882 July 3 Opens a postal department to which can be addressed answers to advertisements Gale Primary Sources gale.com/telegraph Start at the Source. -

Churchill's Dark Side

Degree Programme: Politics with a Minor (EUUB03) Churchill’s Dark Side To What Extent did Winston Churchill have a Dark Side from 1942-1945? Abstract 1 Winston Churchill is considered to be ‘one of history's greatest leaders; without his 1 leadership, the outcome of World War II may have been completely different’0F . This received view has dominated research, subsequently causing the suppression of Churchill’s critical historical revisionist perspective. This dissertation will explore the boundaries of the revisionist perspective, whilst the aim is, simultaneously, to assess and explain the extent Churchill had a ‘dark side’ from 1942-1945. To discover this dark side, frameworks will be applied, in addition to rational and irrational choice theory. Here, as part of the review, the validity of rational choice theory will be questioned; namely, are all actions rational? Hence this research will construct another viewpoint, that is irrational choice theory. Irrational choice theory stipulates that when the rational self-utility maximisation calculation is not completed correctly, actions can be labelled as irrational. Specifically, the evaluation of the theories will determine the legitimacy of Churchill’s dark actions. Additionally, the dark side will be 2 3 assessed utilising frameworks taken from Furnham et al1F , Hogan2F and Paulhus & 4 Williams’s dark triad3F ; these bring depth when analysing the presence of a dark side; here, the Bengal Famine (1943), Percentage Agreement (1944) and Operation 1 Matthew Gibson and Robert J. Weber, "Applying Leadership Qualities Of Great People To Your Department: Sir Winston Churchill", Hospital Pharmacy 50, no. 1 (2015): 78, doi:10.1310/hpj5001-78. -

It's Been a Funny Old Election!

It’s been a funny old election! By Dr. Steven McCabe, Associate Professor, Institute of Design and Economic Acceleration (IDEA) and Senior Fellow, Centre for Brexit Studies, Birmingham City University The title of this blog is derived from a line used by English stage and film actor, comic and singer Stanley Holloway (1 October 1890–30 January 1982) who kept spirits up by entertaining during the second world-war. That this election is, largely, concerned with the issue of Brexit is unsurprising. Perhaps we could do with having our spirits raised as man feel we’ve been in a situation not unlike war since the outcome of the June 2016 referendum on continued European Union (EU) membership. One of the dubious ‘joys’ of a General Election (GE) is in analysing the contents of each political party’s manifesto and comparing their contents. According to the Cambridge Dictionary a manifesto is defined as “a written statement of the beliefs, aims, and policies of an organization, especially a political party” and derives from the Latin word manifestum meaning clear or conspicuous. That this is a peculiar election goes without saying. It’s the third in four years because of David Cameron’s decision to include a commitment in the 2015 Conservative Party election manifesto to have a referendum on EU membership. Cameron is accused of having assumed that this referendum would be easy to win on the official government line of remaining with the EU. An election involving the Tories led by Johnson, and Labour led by Jeremy Corbyn, has long had commentators salivating. -

The Kemper Lecture by Sir Max Hastings

Spring 2011 | Volume 2 | Issue 1 The Magazine of the National Churchill Museum The Kemper Lecture by Sir Max Hastings Plus: The ‘Iron Curtain’ Sculpture Unveiling Ceremony is Announced, Churchill and America by Roland Quinault & 65th Churchill Anniversary Board of Governors MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIREctOR Association of Churchill Fellows William H. Tyler Chairman & Senior Fellow Pebble Beach, California Robert L. DeFer Chesterfield, Missouri A very warm welcome from Fulton Earle H. Harbison, Jr. St. Louis, Missouri Welcome to the second edition of The Churchillian magazine. We William C. Ives have just about recovered from the wonderful 2011 Churchill Chapel Hill, North Carolina Weekend. I know many of you attended in person or supported Hjalma E. Johnson Dade City, Florida the event and let me extend a very big thank you to everyone. The R. Crosby Kemper, III weekend was a tremendous success with both Sir Nigel Sheinwald, Kansas City, Missouri the British Ambassador to the USA, and Sir Max Hastings Barbara D. Lewington delivering tremendously illuminating and insightful talks at the St. Louis, Missouri Churchill dinner and the Kemper Lecture, respectively. Sir Nigel Richard J. Mahoney St. Louis, Missouri spoke of continuity and change in the Anglo-American relationship Jean-Paul Montupet and brought his 30 years of diplomatic experience to bear on this St. Louis, Missouri fascinating topic. Sir Max, as befits an author of his standing, William R. Piper Dr. Rob Havers addresses the crowd St. Louis, Missouri at the Churchill Weekend Brunch. delivered a truly inspiration Kemper Lecture to a packed Church Suzanne D. Richardson of St. -

Churchill's Southern Strategy

fter the evacuation of the Brit- ish Expeditionary Force from Dunkirk in June 1940 and the subsequent fall of France, Churchill’s ANazi Germany held uncontested control of Western Europe. When the Germans failed in their at- tempt to capture the British Isles, they turned their attention toward the east and Southern drove to the outskirts of Moscow before the Red Army counteroffensive began in December 1941. The Soviets pushed the Germans back relentlessly on the Eastern Front with staggering casualties Strategy on both sides, but in the west, the only challenge to the occupation of Europe was aerial bombing by US and British air forces. The Anglo-American armies concentrated on North Africa and Italy. The D-Day invasion There was no front on the ground in was forced on a Western Europe until Operation Overlord, the D-Day landings in Normandy in June reluctant Churchill 1944. D-Day was a huge success, the by the Americans. pivotal event of World War II in Europe. In September 1944, British Prime Minis- ter Winston Churchill told the House of Left: Prime Minister Winston Churchill inspects an Italian village with Field By John T. Correll Marshal Harold Alexander (r). 72 AIR FORCE Magazine / January 2013 Commons the battle of Normandy was “the greatest and most decisive single battle of the entire war.” However, if Churchill and the British had their way, D-Day might not have happened. They did everything they Bettmann/Corbis/AP Images could to head off the American plan to attack across the English Channel. They pressed instead for a strategy focused on the Mediterranean, pushing through the “soft underbelly” of southern Europe, over the Alps and through the Balkans. -

Welcome to the Court of England's New 'Sun King'

Welcome to the Court of England’s New ‘Sun King’ By Dr Steven McCabe, Associate Professor, Institute of Design and Economic Acceleration (IDEA) and Senior Fellow, Centre for Brexit Studies, Birmingham City University Life under new Prime Minister Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson has been, as expected, far from dull. Johnson’s first week has involved a flurry of public appearances intended to indicate his popularity as a ‘man of the people’ as well demonstrating his commitment to the continuance of the United Kingdom. These trips have been fascinating in that if Johnson had hoped to be feted in a way Winston Churchill, someone he claims to be a hero, was as PM during the second-world-war, he will probably have been disappointed. Johnson is reputed to be as thin-skinned as American President Donald Trump. The booing that has accompanied Johnson’s visits to Scotland and Wales may, should he reflect for a few moments in his break-neck schedule, cause him to think that being PM is not as easy as it may seem. As is well known, since childhood when asked what he wished to do when he grew up and answered that he wished to be “world king”, Johnson has long coveted the role of becoming the PM. This was a role he believed he was destined to inherit. Indeed, resonant with Churchill, who, prior to conflict with the Nazis, was regarded as a failure, but was seen as ‘man of the hour’ as PM of a national government dedicated to steadfast resistance against Hitler’s regime. -

Enter Boris Johnson'smind

Enter Boris Johnson’s Mind Directed by Alice Cohen Produced by ARTE France & MORGANE Production PROVISIONAL DELIVERY : MARCH 2021 Summary No one took him seriously, he was seen as a buffoon. “I am more likely to be beheaded Yet he was on the winning side with Brexit in 2016 and then triumphed in the December 2019 legislative by a Frisbee or reincarnated into elections. Boris Johnson is the UK’s new strongman. And he is radically altering his country, leaving an an olive than I am to become indelible mark on it – for better or for worse. The Prime Minister. ” British people and Europe’s future for the next ten years hang on to this eccentric, sad clown’s decisions. Boris Johnson, in French (2013, on the set of FranceTV) Enter Boris Johnson’s mind • 2 Intent A subtle blend of Kennedy, Kardashian and Monty Python, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson defies expectations. With a comfortable majority for five years and the opposition in shambles, the years 2020 and 2021 look to be pivotal for him and his country. For better or for worse. Since 1945, the United Kingdom has undergone two major historical shifts: the invention of the welfare state at the end of the war and the wave of liberalization led by Margaret Thatcher from 1979 onwards. With the exit from the European Union and the coronavirus forcing a strong comeback of state regulation, will 2020 mark a third major turn? Behind his jester’s mask, will Boris Johnson rise to the occasion or lead his country to ruin? Is he, at heart, the United Kingdom’s gravedigger; or the redeemer of British greatness? While the film will mainly cover the most recent developments, we will segue into the political, journalistic and sometimes personal history of - political archives, mainly contextual, historical, the man to better inform his political choices and personal. -

Let Us Now Praise Great Men Bringing the Statesman Back In

Let Us Now Praise Daniel L. Byman and Great Men Kenneth M. Pollack Let Us Now Praise Great Men Bringing the Statesman Back In In January 1762, Prus- sia hovered on the brink of disaster. Despite the masterful generalship of Fred- erick the Great, the combined forces of France, Austria, and Russia had gradually worn down the Prussian army in six years of constant warfare. Aus- trian armies had marched deep into Saxony and Silesia, and the Russians had even sacked Berlin. Frederick’s defeat appeared imminent, and the enemy co- alition intended to partition Prussia to reduce it to the status of a middle Ger- man state no more powerful than Bavaria or Saxony. And then a miracle occurred. The Prusso-phobic Czarina Elizabeth unexpectedly died, only to be succeeded by her son Peter, who idolized the soldier-king. Immediately Peter made peace with Frederick and ordered home the Russian armies. This rever- sal paralyzed the French and Austrians and allowed Frederick to rally his forces. Although Peter was soon ousted by his wife, Catherine, the allied ar- mies never regained their advantage. In the end, Frederick held them off and kept Prussia intact.1 Frederick’s triumph in the Seven Years’ War was essential to Prussia’s even- tual uniªcation of Germany and all that followed from it. Conceiving of Euro- pean history today without this victory is impossible. It is equally impossible to conceive of Prussian victory in 1763 without the death of Elizabeth and Pe- ter’s adoration of Frederick. In the words of Christopher Duffy, “It is curious to reºect that if one lady had lived for a very few weeks longer, historians would by now have analyzed in most convincing detail the reasons for a collapse as ‘inevitable’ as that which overtook the Sweden of Charles XII.”2 In short, had it not been for the idiosyncrasies of one man and one woman, European history would look very, very different. -

A PERSISTENT FIRE the Strategic Ethical Impact of World War I

A PERSISTENT A PERSISTENT FIRE The Strategic Ethical Impact of World War I The Strategic Ethical Impact of World War I World Ethical of Strategic The Impact FIon the GlobalR Profession of EArms on the Global Profession of Arms of the Profession Global on Edited by Timothy S. Mallard and Nathan H. White A PERSISTENT FIRE A PERSISTENT The Strategic Ethical Impact of World War I FIon the GlobalR Profession of EArms Edited by Timothy S. Mallard and Nathan H. White National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. 2019 Published in the United States by National Defense University Press. Portions of this book may be quoted or reprinted without permission, provided that a standard source credit line is included. NDU Press would appreciate a courtesy copy of reprints or reviews. Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Defense or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: International Military Ethics Symposium (2018 : Washington, D.C.), author. | Mallard, Timothy S., editor. | White, Nathan H., editor. | National Defense University Press, issuing body. Title: A persistent fire : the strategic ethical impact of World War I on the global profession of arms / edited by Timothy S. Mallard and Nathan H. White. Other titles: Strategic ethical impact of World War I on the global profession of arms Description: Washington, D.C. : National Defense University Press, [2020] | "The International Military Ethics Symposium occurred from July 30 through August 1, 2018 ..