Who Started the First World War? 35 Notions of Honour, Expectations of a Swift Victory, and Ideas of Social Darwinism’, As a Significant Factor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Secrets and Spies Late at Churchill War Rooms Friday 4 October 2013 6.30Pm – 9.30Pm

Immediate release Secrets and Spies at Churchill War Rooms From September 2013, a series of secret and spy-themed events will take place beneath the streets of Whitehall, in Churchill’s secret underground bunker. These events include a lecture from Simon Pearson on his book The Great Escaper, following the sold out lecture by historian, Clare Mulley’s talk on her new book The Spy Who Loved and an espionage themed late night opening. Secrets and Spies Late at Churchill War Rooms Friday 4 October 2013 6.30pm – 9.30pm Churchill War Rooms will present London’s most unique night out this autumn. Experience Churchill War Rooms as never before, step back in time to a world of 1940s espionage and embark on a secret mission to discover if you have what it takes to reach the standard of a Special Operations Executive (SOE) under Churchill’s government. Take part in a spy challenge, decode hidden devices against the clock and seek out spy bugs planted around the site, using GPS devices. Encounter a SOE agent reenacting some of the most famous secret missions of Second World War and watch an official SOE recruitment film from IWM’s archives. In the spirit of the era, there will be 1940s themed drinks and those who complete the spy challenge will be entered into a draw to win a spy-themed weekend away and a private tour of Churchill War Rooms. 1940s vintage attire encouraged. Tickets: Adults, £17 Concessions, £13.60 Simon Pearson - The Great Escaper Tuesday 15 October 2013 7pm – 9pm (Doors open 6.30pm) Author and Times journalist Simon Pearson will discuss the extraordinary story of Roger Bushell, known as Big X, a prisoner of war noted for masterminding the ‘Great Escape’ at the infamous Stalag Luft III camp. -

Retribution: the Battle for Japan, 1944-45 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

RETRIBUTION: THE BATTLE FOR JAPAN, 1944-45 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Sir Max Hastings | 615 pages | 10 Mar 2009 | Random House USA Inc | 9780307275363 | English | New York, United States Retribution: The Battle for Japan, 1944-45 PDF Book One is the honest and detailed description of Japanese brutality. It invaded colonial outposts which Westerners had dominated for generations, taking absolutely for granted their racial and cultural superiority over their Asian subjects. The book greatly improved my limited knowledge of many of the key figures of the war in the Far East , particularly Macarthur, Chiang Kai Shek and one of the great forgotten British heroes, Bill Slim. The book is amazingly detailed in regards to the battles and the detail and clarity of each element brings into sharp focus the depth of human suffering and courage that so many people went through in this area. He gives one of the best accounts of the Soviet campaign in China and the Kuriles that I have found - given that it is only a section of the book and not a book in and of itself. The US were very reluctant for the Colonial Powers to take up their former territories after the War, to the extent that they refused to help the French in Indo-China, while Britain and Australia for differing reasons were critical of the US efforts to sideline their input to Japan's defeat. It was wildly fanciful to suppose that the consequences of military failure might be mitigated through diplomatic parley. He has presented historical documentaries for television, including series on the Korean War and on Churchill and his generals. -

Jihad-Cum-Zionism-Leninism: Overthrowing the World, German-Style

Jihad-cum-Zionism-Leninism: Overthrowing the World, German-Style Sean McMeekin Historically Speaking, Volume 12, Number 3, June 2011, pp. 2-5 (Article) Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: 10.1353/hsp.2011.0046 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/hsp/summary/v012/12.3.mcmeekin.html Access Provided by Bilkent Universitesi at 11/26/12 5:31PM GMT 2 Historically Speaking • June 2011 JIHAD-CUM-ZIONISM-LENINISM: ISTORICALLY PEAKING H S OVERTHROWING THE WORLD, June 2011 Vol. XII No. 3 GERMAN-STYLE CONTENTS Jihad-cum-Zionism-Leninism: 2 Sean McMeekin Overthrowing the World, German-Style Sean McMeekin Is “Right Turn” the Wrong Frame for 6 American History after the 1960s? t is often said that the First World War David T. Courtwright marks a watershed in modern history. From the mobilization of armies of un- The Politics of Religion in 8 I fathomable size—more than 60 million men put Modern America: A Review Essay on uniforms between 1914 and 1918—to the no Aaron L. Haberman less mind-boggling human cost of the conflict, Military History at the Operational Level: 10 both at the front and beyond it (estimated mili- An Interview with Robert M. Citino tary and civilian deaths were nearly equal, at Conducted by Donald A. Yerxa some 8 million each), the war of 1914 broke all historical precedent in the scale of its devasta- The Birth of Classical Europe: 13 An Interview with Simon Price and Peter tion. Ruling houses that had endured for cen- Thonemann turies—the Romanov, Habsburg, and Conducted by Donald A. -

Stoney Road out of Eden: the Struggle to Recover Insurance For

Scholarly Commons @ UNLV Boyd Law Scholarly Works Faculty Scholarship 2012 Stoney Road Out of Eden: The Struggle to Recover Insurance for Armenian Genocide Deaths and Its Implications for the Future of State Authority, Contract Rights, and Human Rights Jeffrey W. Stempel University of Nevada, Las Vegas -- William S. Boyd School of Law Sarig Armenian David McClure University of Nevada, Las Vegas -- William S. Boyd School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/facpub Part of the Contracts Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, Insurance Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, National Security Law Commons, and the President/Executive Department Commons Recommended Citation Stempel, Jeffrey W.; Armenian, Sarig; and McClure, David, "Stoney Road Out of Eden: The Struggle to Recover Insurance for Armenian Genocide Deaths and Its Implications for the Future of State Authority, Contract Rights, and Human Rights" (2012). Scholarly Works. 851. https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/facpub/851 This Article is brought to you by the Scholarly Commons @ UNLV Boyd Law, an institutional repository administered by the Wiener-Rogers Law Library at the William S. Boyd School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STONEY ROAD OUT OF EDEN: THE STRUGGLE TO RECOVER INSURANCE FOR ARMENIAN GENOCIDE DEATHS AND ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR THE FUTURE OF STATE AUTHORITY, CONTRACT RIGHTS, AND HUMAN RIGHTS Je:jrev' W. Stempel Saris' ArInenian Davi' McClure* Intro d uctio n .................................................... 3 I. The Long Road to the Genocide Insurance Litigation ...... 7 A. The Millet System of Non-Geographic Ethno-Religious Administrative Autonomy ........................... -

Winston Churchill's Rhetoric and the Second World War Written By

Indiana University South Bend Undergraduate Research Journal Keep Calm and Carry On: Winston Churchill's Rhetoric and the Second World War Written by Abraham Maldonado-Orellana Edited by Chloe Lawrence "Of all the talents bestowed upon men, none is so The First World War, having ended in 1918, left instability in its precious as the gift oforatory ... Abandoned by his wake; the world had changed politically and culturally, only to be party betrayed by his friends, stripped of his offices, followed by a global economic depression in the 1930s. Memories of the Great War still resonated in people's minds. Fresh fears of whoever can command this power is still invasion set in as Britain heard the news of Poland's invasion by 1 formidable. " Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union on September 1, 1939. In 1940, the war became very real for the British and it would soon -Winston S. Churchill, 1897 become a pivotal year for the country's new Prime Minister. The Abstract: Battle of France, the evacuation at Dunkirk, The Battle of Britain and Churchill's most famous speeches all occurred during 1940, This article examines Prime Minister Winston Churchill's which one might call "the year of Churchill." role in creating a sense of national solidarity in wartime Britain and establishing an Anglocentric interpretation of World War II Churchill as Orator through his wartime speeches and publications. Churchill's Winston Churchill, a Conservative politician and Member of speeches and addresses during 1940 as well as his memoirs Parliament since 1900, would serve as Prime Minister of Great released after the war were heard and read by an international Britain during the Second World War. -

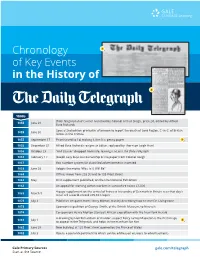

Chronology of Key Events in the History of the Daily Telegraph

Chronology 1 of Key Events in the History of 2 1800s Daily Telegraph And Courier launched by Colonel Arthur Sleigh, price 2d, edited by Alfred 1855 June 29 Bate Richards Special 2nd edition printed in afternoon to report the death of Lord Raglan, C.-in-C. of British 1855 June 30 forces in the Crimea 1855 September 17 Price halved to 1d, making it the first penny paper 1 1855 December 31 Alfred Bate Richards resigns as Editor, replaced by Thornton Leigh Hunt 1856 October 28 “And Courier” dropped from title, leaving it as just The Daily Telegraph 1857 February 17 Joseph Levy buys out ownership of the paper from Colonel Sleigh 1857 Box number system for classified advertisements invented 1858 June 25 Adopts the motto “Was, Is & Will Be” 1860 Offices move from 253 Strand to 135 Fleet Street 1861 May First supplement published, on the International Exhibition 1862 An appeal for starving cotton workers in Lancashire raises £6,000 4-page supplement on the arrival of Princess Alexandra of Denmark in Britain sees that day’s 1863 March 9 issue sell a world-record 205,884 copies 1872 July 3 Publishes despatch from Henry Morton Stanley describing how he met Dr. Livingstone 1873 Sponsors expedition of George Smith, of the British Museum, to Nineveh 1874 Co-sponsors Henry Morton Stanley’s African expedition with the New York Herald A drawing by Hall Richardson of murder suspect Percy Lefroy Mapleton is the first image 1881 July 1 2 to appear in the Telegraph, and helps in the manhunt for him 1882 June 28 New building at 135 Fleet Street opened by the Prince of Wales 1882 July 3 Opens a postal department to which can be addressed answers to advertisements Gale Primary Sources gale.com/telegraph Start at the Source. -

Churchill's Dark Side

Degree Programme: Politics with a Minor (EUUB03) Churchill’s Dark Side To What Extent did Winston Churchill have a Dark Side from 1942-1945? Abstract 1 Winston Churchill is considered to be ‘one of history's greatest leaders; without his 1 leadership, the outcome of World War II may have been completely different’0F . This received view has dominated research, subsequently causing the suppression of Churchill’s critical historical revisionist perspective. This dissertation will explore the boundaries of the revisionist perspective, whilst the aim is, simultaneously, to assess and explain the extent Churchill had a ‘dark side’ from 1942-1945. To discover this dark side, frameworks will be applied, in addition to rational and irrational choice theory. Here, as part of the review, the validity of rational choice theory will be questioned; namely, are all actions rational? Hence this research will construct another viewpoint, that is irrational choice theory. Irrational choice theory stipulates that when the rational self-utility maximisation calculation is not completed correctly, actions can be labelled as irrational. Specifically, the evaluation of the theories will determine the legitimacy of Churchill’s dark actions. Additionally, the dark side will be 2 3 assessed utilising frameworks taken from Furnham et al1F , Hogan2F and Paulhus & 4 Williams’s dark triad3F ; these bring depth when analysing the presence of a dark side; here, the Bengal Famine (1943), Percentage Agreement (1944) and Operation 1 Matthew Gibson and Robert J. Weber, "Applying Leadership Qualities Of Great People To Your Department: Sir Winston Churchill", Hospital Pharmacy 50, no. 1 (2015): 78, doi:10.1310/hpj5001-78. -

Russian Origins of the First World War

The Russian Origins of the First World War The Russian Origins of the First World War Sean McMeekin The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts • London, Eng land 2011 Copyright © 2011 by Sean McMeekin All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data McMeekin, Sean, 1974– The Russian origins of the First World War / Sean McMeekin. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-674-06210-8 (alk. paper) 1. World War, 1914–1918—Causes. 2. World War, 1914–1918—Russia. 3. Russia—Foreign relations—1894–1917. 4. Imperialism—History— 20th century. 5. World War, 1914–1918—Campaigns—Eastern Front. 6. World War, 1914–1918—Campaigns—Middle East. I. Title. D514.M35 2011 940.3'11—dc23 2011031427 For Ayla Contents Abbreviations ix Author’s Note xi Introduction: History from the Deep Freeze 1 1. The Strategic Imperative in 1914 6 2. It Takes Two to Tango: The July Crisis 41 3. Russia’s War: The Opening Round 76 4. Turkey’s Turn 98 5. The Russians and Gallipoli 115 6. Russia and the Armenians 141 7. The Russians in Persia 175 8. Partitioning the Ottoman Empire 194 9. 1917: The Tsarist Empire at Its Zenith 214 Conclusion: The October Revolution and Historical Amnesia 234 Notes 245 Bibliography 289 Acknowledgments 303 Index 307 Maps The Russian Empire on the Eve of World War I 8 The Polish Salient 18 The Peacetime Deployment of Russia’s Army Corps 20 The Initial Mobilization Pattern on the Eastern Front 83 Russian Claims on Austrian and German Territory 91 “The Straits,” and Russian Claims on Them 132 Russia and the Armenians 167 Persia and the Caucasian Front 187 The Partition of the Ottoman Empire 206 The Eastern Front 219 Abbreviations ATASE Askeri Tarih ve Stratejik Etüt Başkanlığı Arşivi (Archive of the Turkish Gen- eral Staff). -

Austria-Hungary and the First World War », Histoire@Politique

Alan Sked, « Austria-Hungary and the First World War », Histoire@Politique. Politique, culture, société, n° 22, janvier-avril 2014 [en ligne, www.histoire-politique.fr] Austria-Hungary and the First World War Alan Sked In a lecture to the Royal Historical Society some years ago,1 I2 distinguished between two schools of thought regarding the role of the Habsburg Monarchy in the origins of the First World War. The first regarded the failure of the dynasty to implement domestic reforms, particularly some timely, well-designed scheme for federal reorganization, as having forced it in 1914 to go to war to prevent the ‘nationality question’ from destabilizing, indeed destroying it from within. This school of thought was particularly associated with American historians. The second school, associated mainly with British historians, argued that the ‘nationality question’ was irrelevant in 1914; war came about, instead, on account of questions of foreign policy and dynastic honour or prestige. I myself have always supported this second viewpoint which is clear from my Decline and Fall of the Habsburg Empire, 1815-1918 (2001).3 In it I argue that the decision to declare war on Serbia was explicable though hardly rational, given the Monarchy’s military unpreparedness and the likelihood of a world war ensuing, and given that Franz Joseph in the past had managed to co-exist with a united Germany and Italy after successful military challenges to Austria’s leadership in both these countries. There is now, of course, a huge literature on the origins of the First World War, and a large one on a variety of aspects of the ‘nationality question’ inside the Monarchy in the period leading up to 1914. -

View the Full Conference Program

COVER: Cover of “Dos revolutsyonere rusland” (Revolutionary Russia), an illustrated anthology of current events in Russia published by the Jewish Labor Bund in New York, 1917. YIVO Library. YIVO INSTITUTE FOR JEWISH RESEARCH PRESENTS CONFERENCE NOVEMBER 5 AND 6, 2017 — CO-SPONSORED BY — — RECEPTION SPONSOR — 1 THE TWO DEFINING MOMENTS of the last century were, arguably, the Holocaust and the Russian Revolution. The tragic impact of the Holocaust on Jews is self-evident; their prominent, if also profoundly paradoxical, role in the Russian Revolution is the subject of this pathbreaking YIVO conference. The Russian Revolution liberated the largest Jewish community in the world. It also opened the floodgates for the greatest massacre of Jews before the Second World War amid the civil war and its aftermath in 1918-21. Once the Bolshevik rule was then consolidated, Jews entered into nearly every sphere of Russian life while, in time, much of the singular richness of Jewish cultural life in Russia was flattened, eventually obliterated. 2 SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 5, 2017 MONDAY, NOVEMBER 6, 2017 9:00am JONATHAN BRENT, 9:00am DAVID MYERS, President, CJH Executive Director & CEO, YIVO Introductory Remarks Introductory Remarks KEYNOTE ELISSA BEMPORAD KEYNOTE SAMUEL KASSOW From Berdichev to Minsk and Setting the Stage for 1917 Onward to Moscow: The Jews and the Bolshevik Revolution 10:00am CATRIONA KELLY SESSION 1 The End of Empire: Jewish Children 10:00am ZVI GITELMAN in the Age of Revolution LEADING SESSION 1 The Rise and Fall of Jews in the Soviet Secret -

Stalin's War and Peace by Nina L. Khrushcheva

Stalin’s War and Peace by Nina L. Khrushcheva - Project Syndicate 5/7/21, 12:57 PM Global Bookmark Stalin’s War and Peace May 7, 2021 | NINA L. KHRUSHCHEVA Sean McMeekin, Stalin’s War: A New History of World War II, Allen Lane, London; Basic Books, New York, 2021. Jonathan Haslam, The Spectre of War: International Communism and the Origins of World War II, Princeton University Press, 2021. Norman M. Naimark, Stalin and the Fate of Europe: The Postwar Struggle for Sovereignty, Harvard University Press, 2019. Francine Hirsch, Soviet Judgment at Nuremberg: A New History of the International Military Tribunal after World War II, Oxford University Press, 2020. MOSCOW – From the 2008 war in Georgia to the 2014 annexation of Crimea and the build- up of troops along Ukraine’s eastern and southern borders just this spring, Russia’s actions in recent years have been increasingly worrying. Could history – in particular, the behavior of Joseph Stalin’s Soviet Union after World War II – give Western leaders the insights they need to mitigate the threat? The authors of several recent books about Stalin seem to think so. But not everyone gets the story right. Instead, modern observers often fall into the trap of reshaping history to fit prevailing ideological molds. This has fed an often-sensationalized narrative that is not only unhelpful, but that also plays into Russian President Vladimir Putin’s hands. Nowhere is this more obvious than in the perception, popular in the West, that Putin is a strategic genius – always thinking several moves ahead. Somehow, Putin anticipates his https://www.project-syndicate.org/onpoint/stalin-putin-russia-rel…ad5b7d8-3e09706d97-104308209&mc_cid=3e09706d97&mc_eid=b29a3cca96 Page 1 of 8 Stalin’s War and Peace by Nina L. -

It's Been a Funny Old Election!

It’s been a funny old election! By Dr. Steven McCabe, Associate Professor, Institute of Design and Economic Acceleration (IDEA) and Senior Fellow, Centre for Brexit Studies, Birmingham City University The title of this blog is derived from a line used by English stage and film actor, comic and singer Stanley Holloway (1 October 1890–30 January 1982) who kept spirits up by entertaining during the second world-war. That this election is, largely, concerned with the issue of Brexit is unsurprising. Perhaps we could do with having our spirits raised as man feel we’ve been in a situation not unlike war since the outcome of the June 2016 referendum on continued European Union (EU) membership. One of the dubious ‘joys’ of a General Election (GE) is in analysing the contents of each political party’s manifesto and comparing their contents. According to the Cambridge Dictionary a manifesto is defined as “a written statement of the beliefs, aims, and policies of an organization, especially a political party” and derives from the Latin word manifestum meaning clear or conspicuous. That this is a peculiar election goes without saying. It’s the third in four years because of David Cameron’s decision to include a commitment in the 2015 Conservative Party election manifesto to have a referendum on EU membership. Cameron is accused of having assumed that this referendum would be easy to win on the official government line of remaining with the EU. An election involving the Tories led by Johnson, and Labour led by Jeremy Corbyn, has long had commentators salivating.