Diversity Computing | ACM Interactions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Changing Shape of the Computing World

Outside the Box — The Changing Shape of the Computing World Steve Cunningham Computer Science California State University Stanislaus Turlock, CA 95382 [email protected] http://www.cs.csustan.edu/~rsc Something happened to computing while many of us were busy practicing or teaching our craft, and computing is not quite the same thing we learned. We can ignore this change and others will take our place and teach about it, but they will not have the context and the skill to understand the technology behind it and to carry it forward to the success it should have. And if others carry that torch, computer science will be stunted because we didn't recognize and respond to the opportunity. What happened? Simply this—that Xerox and Apple and, yes, Microsoft opened up the box labeled “CAUTION: Computer Inside” and let the user into the computing picture. Users responded hesitantly but increasingly eagerly and now expect the computer to work for them instead of their working for the computer. Every application now in wide use, and any system that supports a general market, has evolved to meet that expectation. Any computing education that does not pay attention to the user’s role in computing is missing the most vibrant and exciting part of computing today. As it says at the top of this page, you are reading an editorial, not an academic paper. As an editorial, this note represents my personal passion and commitment to the user communication part of computing that the “official” computing establishment has long discounted, and I appreciate John Impagliazzo’s offer of this forum to make my case that computer science is missing the boat in not understanding the need to reshape computer science education to fill this void. -

Jacob O. Wobbrock, Ph.D. Curriculum Vitae Professor, the Information School [email protected] by Courtesy, Paul G

20-Sept-2021 1 of 29 Jacob O. Wobbrock, Ph.D. Curriculum Vitae Professor, The Information School [email protected] By Courtesy, Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering Homepage Director, ACE Lab Google Scholar Founding Co-Director, CREATE Center University of Washington Box 352840 Seattle, WA, USA 98195-2840 BIOGRAPHY______________________________________________________________________________________________ Jacob O. Wobbrock is a Professor of human-computer interaction (HCI) in The Information School, and, by courtesy, in the Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering at the University of Washington, which U.S. News ranked the 8th best global university for 2021. Prof. Wobbrock’s work seeks to scientifically understand people’s experiences of computers and information, and to improve those experiences by inventing new interactive technologies, especially for people with disabilities. His specific research topics include input & interaction techniques, human performance measurement & modeling, HCI research & design methods, mobile computing, and accessible computing. Prof. Wobbrock has co-authored ~200 publications and 19 patents, receiving 25 paper awards, including 7 best papers and 8 honorable mentions from ACM CHI, the flagship conference in HCI. For his work in accessible computing, he received the 2017 SIGCHI Social Impact Award and the 2019 SIGACCESS ASSETS Paper Impact Award. He was named the #1 Most Influential Scholar in HCI by the citation-ranking system AMiner in 2018 and 2021, and was runner-up in 2020. He was also inducted into the prestigious CHI Academy in 2019. His work has been covered in The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Huffington Post, USA Today, and other outlets. He is the recipient of an NSF CAREER award and 7 other National Science Foundation grants. -

Meredith Ringel Morris [email protected], [email protected] Google Scholar Page

Meredith Ringel Morris [email protected], [email protected] http://merrie.info, Google Scholar page OVERVIEW I am an internationally-recognized expert in Human Computer Interaction (HCI), focusing on the design, development, and evaluation of collaborative, social, and accessible technologies, including working at the boundary of HCI and AI to develop responsible AI-based technologies that enhance the capabilities of all people. I am seeking opportunities to do world-changing research and/or lead a high-impact team at the intersection of HCI and AI, drawing on my unique expertise in collaborative and accessible computing to invent the next generation of inclusive technologies. Areas of expertise: gesture interfaces, collaborative technologies, social media, social search, Q&A systems, information retrieval, crowdsourcing, accessible and assistive technologies, digital inclusion, universal design, human-centered AI, responsible AI EDUCATION 2006 Ph.D. in Computer Science, Stanford University 2003 M.S. in Computer Science, Stanford University 2001 Sc.B. in Computer Science, Brown University (Magna Cum Laude) PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2021 - present Google Research Director and Principal Scientist, People + AI Research 2006 - 2021 Microsoft Research Sr. Principal Researcher and Research Manager • Founder and Research Manager of the Ability group (2018 – 2020) • Redmond Lab Leadership Team member (2020 - 2021) • Research Area Manager for Interaction, Accessibility, and Mixed Reality (2020 – 2021) 2001 – 2006 Stanford University Department -

Dina Goldin · Scott A. Smolka · Peter Wegner (Eds.) Dina Goldin Scott A

Dina Goldin · Scott A. Smolka · Peter Wegner (Eds.) Dina Goldin Scott A. Smolka Peter Wegner (Eds.) Interactive Computation The New Paradigm With 84 Figures 123 Editors Dina Goldin Scott A. Smolka Brown University State University of New York at Stony Brook Computer Science Department Department of Computer Science Providence, RI 02912 Stony Brook, NY 11794-4400 USA USA [email protected] [email protected] Peter Wegner Brown University Computer Science Department Providence, RI 02912 USA [email protected] Cover illustration: M.C. Escher’s „Whirlpools“ © 2006 The M.C. Escher Company-Holland. All rights reserved. www.mcescher.com Library of Congress Control Number: 2006932390 ACM Computing Classification (1998): F, D.1, H.1, H.5.2 ISBN-10 3-540-34666-X Springer Berlin Heidelberg New York ISBN-13 978-3-540-34666-1 Springer Berlin Heidelberg New York This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broad- casting, reproduction on microfilm or in any other way, and storage in data banks. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the German Copyright Law of September 9, 1965, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. Violations are liable for prosecution under the German Copyright Law. Springer is a part of Springer Science+Business Media springer.com © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2006 The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant pro- tective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

A Brief History of Human Computer Interaction Technology

A Brief History of Human Computer Interaction Technology Brad A. Myers Carnegie Mellon University School of Computer Science Technical Report CMU-CS-96- 163 and Human Computer Interaction Institute Technical Report CMU-HCII-96-103 December, 1996 Please cite this work as: Brad A. Myers. "A Brief History of Human Computer Interaction Technology." ACM interactions. Vol. 5, no. 2, March, 1998. pp. 44-54. Human Computer Interaction Institute School of Computer Science Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, PA 15213-3891 [email protected] Abstract This article summarizes the historical development of major advances in human- computer interaction technology, emphasizing the pivotal role of university research in the advancement of the field. Copyright (c) 1996 -- Carnegie Mellon University A short excerpt from this article appeared as part of "Strategic Directions in Human Computer Interaction," edited by Brad Myers, Jim Hollan, Isabel Cruz, ACM Computing Surveys, 28(4), December 1996 This research was partially sponsored by NCCOSC under Contract No. N66001-94-C- 6037, Arpa Order No. B326 and partially by NSF under grant number IRI-9319969. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of NCCOSC or the U.S. Government. Keywords: Human Computer Interaction, History, User Interfaces, Interaction Techniques. 1. Introduction Research in Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) has been spectacularly successful, and has fundamentally changed computing. Just one example is the ubiquitous graphical interface used by Microsoft Windows 95, which is based on the Macintosh, which is based on work at Xerox PARC, which in turn is based on early research at the Stanford Research Laboratory (now SRI) and at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. -

Bridging the Digital Divide with Universal Usability

Bridging the Digital Divide with Universal Usability Ben Shneiderman, University of Maryland for ACM Interactions (March/April 2001) Draft: December 31, 2000 How do you explain a trashcan to a culture that doesn’t have one? How do you describe a “stop loss limit order” to retirees managing their funds? Can you design a text-only interface that conveys the contents and experience of an animated Flash presentation? These puzzles emerged during the first ACM Conference on Universal Usability (http://www.acm.org/sigchi/cuu/), held on November 15-17, 2000 near Washington, DC. The international group of organizers, presenters, and attendees of this conference shared an unusual commitment and passion for making information and communications services accessible, usable, and useful. They want to see effective healthcare services and appealing distance education. They want to create successful e-commerce and accessible government services for all. Realizing these possibilities requires more than low-cost hardware or broadband networks. These mass-market services are often too complex, unusable, or irrelevant for too many users [1]; usability and design become the keys to success. The source of these problems was often attributed to designers who make incorrect assumptions about user knowledge. This leads to difficulties with technical terminology and advanced concepts that are not balanced by adequate online help or live assistance. Unfortunately, most designers never see the pain they inflict on novice and even expert users. These problems have contributed to the growing digital divide in internet technology adoption levels between low- income poorly-educated and high-income well-educated users [2]. -

Communications of the Acm

COMMUNICATIONS CACM.ACM.ORG OF THEACM 10/2015 VOL.58 NO.10 Discovering Genes Involved in Disease and the Mystery of Missing Heritability Crash Consistency Concerns Rise about AI Seeking Anonymity in an Internet Panopticon What Can Be Done about Gender Diversity in Computing? A Lot! Association for Computing Machinery Previous A.M. Turing Award Recipients 1966 A.J. Perlis 1967 Maurice Wilkes 1968 R.W. Hamming 1969 Marvin Minsky 1970 J.H. Wilkinson 1971 John McCarthy 1972 E.W. Dijkstra 1973 Charles Bachman 1974 Donald Knuth 1975 Allen Newell 1975 Herbert Simon 1976 Michael Rabin 1976 Dana Scott 1977 John Backus ACM A.M. TURING AWARD 1978 Robert Floyd 1979 Kenneth Iverson 1980 C.A.R Hoare NOMINATIONS SOLICITED 1981 Edgar Codd 1982 Stephen Cook Nominations are invited for the 2015 ACM A.M. Turing Award. 1983 Ken Thompson 1983 Dennis Ritchie This is ACM’s oldest and most prestigious award and is presented 1984 Niklaus Wirth annually for major contributions of lasting importance to computing. 1985 Richard Karp 1986 John Hopcroft Although the long-term influences of the nominee’s work are taken 1986 Robert Tarjan into consideration, there should be a particular outstanding and 1987 John Cocke 1988 Ivan Sutherland trendsetting technical achievement that constitutes the principal 1989 William Kahan claim to the award. The recipient presents an address at an ACM event 1990 Fernando Corbató 1991 Robin Milner that will be published in an ACM journal. The award is accompanied 1992 Butler Lampson by a prize of $1,000,000. Financial support for the award is provided 1993 Juris Hartmanis 1993 Richard Stearns by Google Inc. -

A Moving Target—The Evolution of Human-Computer Interaction

A Moving Target—The Evolution of Human-Computer Interaction Jonathan Grudin Revision of a chapter in J. Jacko (Ed.), Human-Computer Interaction Handbook (3rd Edition), Taylor & Francis, 2012. 1 PREAMBLE: HISTORY IN A TIME OF RAPID OBSOLESCENCE 3 1985–1995: GRAPHICAL USER INTERFACES SUCCEED 21 Why Study the History of Human-Computer Interaction? CHI Embraces Computer Science Definitions: HCI, CHI, HF&E, IT, IS, LIS 4 HF&E Maintains a Nondiscretionary Use Focus 22 Shifting Context: Moore’s Law and Inflation IS Extends Its Range 23 Collaboration Support: OIS Gives Way to CSCW HUMAN-TOOL INTERACTION AND INFORMATION PROCESSING Participatory Design and Ethnography 24 AT THE DAWN OF COMPUTING LIS: A Transformation Is Underway 25 Origins of Human Factors Origins of the Focus on Information 5 1995–2010: THE INTERNET ERA ARRIVES AND SURVIVES A Paul Otlet and the Mundaneum 6 BUBBLE 26 Vannevar Bush and Microfilm Machines The Formation of AIS SIGHCI Digital Libraries and the Rise of Information Schools 27 1945–1955: MANAGING VACUUM TUBES 7 HF&E Embraces Cognitive Approaches Three Roles in Early Computing A Wave of New Technologies & CHI Embraces Design 28 Grace Hopper: Liberating Computer Users 8 The Dot-Com Collapse 29 1955–1965: TRANSISTORS, NEW VISTAS LOOKING BACK: CULTURES AND BRIDGES Supporting Operators: First Formal HCI Studies Discretion as a Major Differentiator 29 Visions and Demonstrations 9 Disciplinary, Generational, and Regional Cultures 30 J.C.R. Licklider at BBN and ARPA John McCarthy, Christopher Strachey, Wesley Clark LOOKING FORWARD: -

Education Board FY 2020

FY’20 ACM Education Board and Education Advisory Committee For the Period: July 1, 2019 - June 30, 2020 Chris Stephenson and Jane Prey, Co-Chairs Beth Hawthorne, Vice Chair Mehran Sahami, Past Chair Executive Summary This report summarizes the activities of the ACM Education Board and the Education Advisory Committee (EAC) in FY’20 and outlines priorities for FY’21. The membership of each organization is available from acm.org/education/education-governance. Below is a list of the Education Board’s and EAC’s major accomplishments for this past year. Curricular Volumes In Progress: ● CC2020 ● Data Science ● Computer Science Interim (MOU under development) ● IS2020 (in partnership with AIS) Completed: ● ACM Curriculum Guidelines for Associate-Degree Programs in Cybersecurity ● ACM Curriculum Guidelines for Two-Year Transfer Programs in Information Technology International Efforts ● Educational efforts in China ● Educational efforts in India ● Educational efforts in Europe/Informatics for All ● Educational efforts in Brazil Current Task Forces and Other Projects 1. Education in Ethics and Computing task force 2. Actionable Computing Enrollment and Retention (ACER) Data Analysis task force 3. Computing + X Curriculum task force 4. Resources for Instructors to Improve Teaching and Peer Mentoring Practices (EngageCSEdu) 5. NDC study 6. Learning@Scale conference Activities and Engagements with ACM SIGs and Other Groups ACM Organizations: ACM CCECC, ACM India, ACM China, ACM Europe, SIGCAS, SIGCHI, SIGCSE, SIGGRAPH, SIGHPC, SIGITE, TOCE 1 Affiliated -

SIGCHI Executive Committee Meeting Notes 2012/07

SIGCHI EC Meeting July 26-28, 2012 NY, NY USA __________________________________________________________________________ Present: Gerrit van der Veer, Elizabeth Churchill, Allison Druin, Gary Olson, Debra Venedam (ACM), Jofish Kaye, Paula Kotze, Dan Olsen, John Karat, John Thomas, Philippe Palanque, Jonathan Lazar, John (Scooter) Morris, Tuomo Kujala, Fred Sampson, Zhengjie Liu, Ashley Cozzi, Kia Hook (via phone and online), Jenny Preece (July 27-28) July 26: Philippe, Dan, Gary, Jonathan, Scooter, Gerrit work with ACM staff on specific topics: Late Morning: Getting to know each other - our worlds outside SIGCHI: each: a 5 minute Bio where “SIGCHI” is the Forbidden Word Gerrit- over 50 yrs in university research on computers and psychology in Netherlands and other countries. Musical Instruments. Philippe- university in Southern France (Toulouse), in computer science. Formerly farmer and Armagnac distillery. Allison- 15 yrs at University of Maryland’s HCIL with a research focus on kids & HCI; mentors women for advancement in academia Scooter- University of Calf. San Francisco RBVI focuses on network visualization- 19 yrs at Genentech- swims a lot Debra- ACM EC liaison and cool mom Zhengjie- involved with HCI since 1989, experience in Germany and UK- work with industry on UX social media Tuomo- University of Jyvaskyla- lots of trees, lakes, snow. His research is on distraction, multi- tasking. JohnK- Worked for IBM doing HCI research for 29 years, then moved to California where he can walk to the ocean with Clare-Marie and Zachary. Worked for UN Development Programme in Bangladesh. Arlo Guthrie says John can keep the royalties from his Alice’s Restaurant performances (may not be legally binding document). -

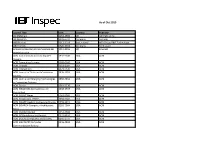

As of Oct 2019

As of Oct 2019 Journal Title ISSN Country Publisher 2D Materials 2053-1583 UK IOP Publishing 3D Research 2092-6731 Germany Springer ABB Review 1013-3119 Switzerland ABB Group R&D Technology ABI Technik 0720-6763 Germany De Gruyter Academia Revista Latinoamericana de 1012-8255 UK Emerald Administracion ACM Communications in Computer 1932-2240 USA ACM Algebra ACM Computing Surveys 0360-0300 USA ACM ACM Inroads 2153-2184 USA ACM ACM Interactions 1072-5520 USA ACM ACM Journal of Data and Information 1936-1955 USA ACM Quality ACM Journal on Emerging Technologies 1550-4832 USA ACM in Computing Systems ACM Queue 1542-7730 USA ACM ACM SIGACCESS Accessibility and 1558-2337 USA ACM Computing ACM SIGACT News 0163-5700 USA ACM ACM SIGAda Ada Letters 1094-3641 USA ACM ACM SIGAPP Applied Computing Review 1559-6915 USA ACM ACM SIGARCH Computer Architecture 0163-5964 USA ACM News ACM SIGBED Review 1551-3688 USA ACM ACM SIGBioinformatics Record 2331-9291 USA ACM ACM SIGCAS Computers and Society 0095-2737 USA ACM ACM SIGCOMM Computer 0146-4833 USA ACM Communication Review ACM SIGCSE Bulletin 0097-8418 USA ACM ACM SIGecom Exchanges 1551-9031 USA ACM ACM SIGEVOlution 1931-8499 USA ACM ACM SIGIR Forum 0163-5840 USA ACM ACM SIGKDD Explorations Newsletter 1931-0145 USA ACM ACM SIGLOG News 2372-3491 USA ACM ACM SIGMETRICS Performance 0163-5999 USA ACM Evaluation Review ACM SIGMIS Database for Advances in 0095-0033 USA ACM Information Systems ACM SIGMOD Record 0163-5808 USA ACM ACM SIGOPS Operating Systems Review 0163-5980 USA ACM ACM SIGPLAN Fortran Forum 1061-7264 -

CHI 2014 Printed Program Available (PDF)

WELCOME FROM THE CHAIRS Welcome to CHI 2014 CHI is more than a conference, it is an international community along, join the crowd and be energised by our speakers who will each of researchers and practitioners who want to make a difference. bring in their experience of the Big Picture to inspire us. The talks will be Everything we do is focused on uncovering, critiquing and celebrating short - twenty minutes - and then the rest of the day’s programme will radically new ways for people and technology to evolve together. begin. We are also delighted to host a timely retrospective exhibition on People in their everyday contexts, in diverse regions of the world, from wearable technology curated by Thad Starner and Clint Zeagler. very different backgrounds, with alternative outlooks on life drive this innovation. As you take part in the conference sessions we really hope CHI 2014 also includes two days of focused workshops and four days you will experience how powerful this people-centred approach to of technical content, including CHI’s prestigious technical program, with technological transformation can be. 15 parallel sessions of rigorously reviewed research Papers, engaging Panels, Case Studies and Special Interest Groups (SIGs), an extensive CHI as a conference is now in its 32nd year and has grown to become Course program and invited talks from SIGCHI’s award winners: the premier international forum on human-computer interaction, Steve Whittaker, Gillian Grampton Smith and Richard Ladner. We also gathering us all to share innovative interactive insights that shape host student research, design, and game competitions, provocative people’s lives.