A Moving Target—The Evolution of Human-Computer Interaction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resurrect Your Old PC

Resurrect your old PCs Resurrect your old PC Nostalgic for your old beige boxes? Don’t let them gather dust! Proprietary OSes force users to upgrade hardware much sooner than necessary: Neil Bothwick highlights some great ways to make your pensioned-off PCs earn their keep. ardware performance is constantly improving, and it is only natural to want the best, so we upgrade our H system from time to time and leave the old ones behind, considering them obsolete. But you don’t usually need the latest and greatest, it was only a few years ago that people were running perfectly usable systems on 500MHz CPUs and drooling over the prospect that a 1GHz CPU might actually be available quite soon. I can imagine someone writing a similar article, ten years from now, about what to do with that slow, old 4GHz eight-core system that is now gathering dust. That’s what we aim to do here, show you how you can put that old hardware to good use instead of consigning it to the scrapheap. So what are we talking about when we say older computers? The sort of spec that was popular around the turn of the century. OK, while that may be true, it does make it seem like we are talking about really old hardware. A typical entry-level machine from six or seven years ago would have had something like an 800MHz processor, Pentium 3 or similar, 128MB of RAM and a 20- 30GB hard disk. The test rig used for testing most of the software we will discuss is actually slightly lower spec, it has a 700MHz Celeron processor, because that’s what I found in the pile of computer gear I never throw away in my loft, right next to my faithful old – but non-functioning – Amiga 4000. -

The Mother of All Demos

UC Irvine Embodiment and Performativity Title The Mother of All Demos Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/91v563kh Author Salamanca, Claudia Publication Date 2009-12-12 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Mother of All Demos Claudia Salamanca PhD Student, Rhetoric Department University of California Berkeley 1929 Fairview St. Apt B. Berkeley, CA, 94703 1 510 735 1061 [email protected] ABSTRACT guide situated at the mission control and from there he takes us This paper analyses the documentation of the special session into another location: a location that Levy calls the final frontier. delivered by Douglas Engelbart and William English on This description offered by Levy as well as the performance in December 9, 1968 at the Fall Computer Joint Conference in San itself, shows a movement in time and space. The name, “The Francisco. Mother of All Demos,” refers to a temporality under which all previous demos are subcategories of this performance. Furthermore, the name also points to a futurality that is constantly Categories and Subject Descriptors in production: all future demos are also included. What was A.0 [Conference Proceedings] delivered on December 9, 1968 captured the past but also our future. In order to explain this extended temporality, Engelbart’s General Terms demo needs to be addressed not only from the perspective of the Documentation, Performance, Theory. technological breakthroughs but also the modes in which they were delivered. This mode of futurality goes beyond the future simple tense continuously invoked by rhetorics of progress and Keywords technology. The purpose of this paper is to interrogate “The Demo, medium performance, fragmentation, technology, Mother of All Demos” as a performance, inquiring into what this augmentation system, condensation, space, body, mirror, session made and is still making possible. -

Computer Organization and Design

THIRD EDITION Computer Organization Design THE HARDWARE/SOFTWARE INTERFACE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Figures 1.9, 1.15 Courtesy of Intel. Computers in the Real World: Figure 1.11 Courtesy of Storage Technology Corp. Photo of “A Laotian villager,” courtesy of David Sanger. Figures 1.7.1, 1.7.2, 6.13.2 Courtesy of the Charles Babbage Institute, Photo of an “Indian villager,” property of Encore Software, Ltd., India. University of Minnesota Libraries, Minneapolis. Photos of “Block and students” and “a pop-up archival satellite tag,” Figures 1.7.3, 6.13.1, 6.13.3, 7.9.3, 8.11.2 Courtesy of IBM. courtesy of Professor Barbara Block. Photos by Scott Taylor. Figure 1.7.4 Courtesy of Cray Inc. Photos of “Professor Dawson and student” and “the Mica micromote,” courtesy of AP/World Wide Photos. Figure 1.7.5 Courtesy of Apple Computer, Inc. Photos of “images of pottery fragments” and “a computer reconstruc- Figure 1.7.6 Courtesy of the Computer History Museum. tion,” courtesy of Andrew Willis and David B. Cooper, Brown University, Figure 7.33 Courtesy of AMD. Division of Engineering. Figures 7.9.1, 7.9.2 Courtesy of Museum of Science, Boston. Photo of “the Eurostar TGV train,” by Jos van der Kolk. Figure 7.9.4 Courtesy of MIPS Technologies, Inc. Photo of “the interior of a Eurostar TGV cab,” by Andy Veitch. Figure 8.3 ©Peg Skorpinski. Photo of “firefighter Ken Whitten,” courtesy of World Economic Forum. Figure 8.11.1 Courtesy of the Computer Museum of America. Graphic of an “artificial retina,” © The San Francisco Chronicle. -

Modest Talk at Guadec/Desktop Summit 2009

static void _f_do_barnacle_install_properties(GObjectClass *gobject_class) { GParamSpec *pspec; Modest /* Party code attribute */ pspec = g_param_spec_uint64 Creating a modern mobile (F_DO_BARNACLE_CODE, "Barnacle code.", "Barnacle code", 0, email client with gnome G_MAXUINT64, G_MAXUINT64 /* default value */, G_PARAM_READABLE technologies | G_PARAM_WRITABLE | G_PARAM_PRIVATE); g_object_class_install_property (gobject_class, F_DO_BARNACLE_PROP_CODE, José Dapena Paz jdapena AT igalia DOT com Sergio Villar Senín svillar AT igalia DOT com Brief history ● Started in 2006 ● 2007 Targeted for Maemo Chinook ● December 2007 first beta release ● 2008 Maemo Diablo ● 2009 Development becomes public. Repository moved to git How big is it? ● Modest Total Physical Source Lines of Code (SLOC) = 104,675 ● Tinymail Total Physical Source Lines of Code (SLOC) = 179,363 Goals Easy to use Embedded devices ● Small resources ● Small screen ● Small storage Multiple UI. Common logic Gnome UI Maemo 4/Diablo UI Maemo 5/Fremantle UI Coming soon... Support for most common email protocols ● IMAP ● POP ● SMTP Push email IMAP IDLE Extensibility New plugin architecture Architecture Architecture Gtk+ Hildon 2 GLib Pango GConf GtkHTML Modest Modest Modest Alarm MCE Abook plugin Xproto Plugin Yproto libtinymail-gtk libtinymail-maemo libtinymail-camel camel-lite Camel Xproto Tinymail Camel Yproto IMAP POP SMTP Xproto daemon Camel-lite mmap-ed summaries ● Very reduced memory usage ● Very compact representation on disk ● Efficient use of memory (thx kernel) IMAP IDLE support Camel features out-of-the-box ● Great support for MIME ● Stream based API ● Modular extensible Tinymail ● Multiple platforms ● Simplifies Camel API's ● Integrated Glib mainloop ● Gtk+ widgets ● Asynchronous API. Responsive UI ● Modular design Modest ● Message view based on gtkhtml ● Rich message editor based on wpeditor ● Offline read of messages and folders ● Integration with network status libraries Migration to Hildon 2.2 Hildon 2.2/Fremantle philosophy ● Proper experience with finger in small screens. -

Communicative Capital for Prosthetic Agents Patrick M

This is an unpublished technical report undergoing peer review, not a final typeset article. First draft: July 23, 2016. Current Draft: November 9, 2017. Communicative Capital for Prosthetic Agents Patrick M. Pilarski 1;2∗, Richard S. Sutton 2, Kory W. Mathewson 1;2, Craig Sherstan 1;2, Adam S. R. Parker 1;2, and Ann L. Edwards 1;2 1Division of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Department of Medicine, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada 2Reinforcement Learning and Artificial intelligence Laboratory, Department of Computing Science, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada Correspondence*: Patrick M. Pilarski, Division of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Department of Medicine, 5-005 Katz Group Centre for Pharmacy and Health Research, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada, T6G 2E1. [email protected] ABSTRACT This work presents an overarching perspective on the role that machine intelligence can play in enhancing human abilities, especially those that have been diminished due to injury or illness. As a primary contribution, we develop the hypothesis that assistive devices, and specifically artificial arms and hands, can and should be viewed as agents in order for us to most effectively improve their collaboration with their human users. We believe that increased agency will enable more powerful interactions between human users and next generation prosthetic devices, especially when the sensorimotor space of the prosthetic technology greatly exceeds the conventional control and communication channels available to a prosthetic user. To more concretely examine an agency-based view on prosthetic devices, we propose a new schema for interpreting the capacity of a human-machine collaboration as a function of both the human’s and machine’s degrees of agency. -

Radical Atoms: Beyond Tangible Bits, Toward Transformable Materials Cover Story by Hiroshi Ishii, Dávid Lakatos, Leonardo Bonanni, and Jean-Baptiste Labrune

Volume XIX.1 | january + february 2012 Radical Atoms: Beyond Tangible Bits, Toward Transformable Materials Cover Story by Hiroshi Ishii, Dávid Lakatos, Leonardo Bonanni, and Jean-Baptiste Labrune Association for Computing Machinery CoVer storY Radical Atoms: Beyond Tangible Bits, Toward Transformable Materials Hiroshi Ishii MIT Media Lab | [email protected] Dávid Lakatos MIT Media Lab | [email protected] Leonardo Bonanni MIT Media Lab | [email protected] Jean-Baptiste Labrune MIT Media Lab | [email protected] Graphical user interfaces (GUIs) appearance dynamically, so they let users see digital informa- are as reconfigurable as pixels on tion only through a screen, as if a screen. Radical Atoms is a vision looking into a pool of water, as for the future of human-material depicted in Figure 1 on page 40. interactions, in which all digital We interact with the forms below information has physical mani- through remote controls, such as festation so that we can interact a mouse, a keyboard, or a touch- directly with it—as if the iceberg screen (Figure 1a). Now imagine had risen from the depths to reveal an iceberg, a mass of ice that pen- its sunken mass (Figure 1c). etrates the surface of the water 2 012 and provides a handle for the mass From GuI to TuI beneath. This metaphor describes Humans have evolved a heightened tangible user interfaces: They act ability to sense and manipulate Februar y as physical manifestations of com- the physical world, yet the digital + putation, allowing us to interact world takes little advantage of our directly with the portion that is capacity for hand-eye coordina- made tangible—the “tip of the ice- tion. -

REBECCA E. GRINTER ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR School of Interactive Computing College of Computing Georgia Institute of Technology Atlanta, GA 30332-0760

CURRICULUM VITAE REBECCA E. GRINTER ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR School of Interactive Computing College of Computing Georgia Institute of Technology Atlanta, GA 30332-0760 DIGITAL COORDINATES Email: [email protected], [email protected] Interactive Computing: AIM, LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter, Foursquare, Wordpress all beki70 r---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------o Revised January 13, 2011 Complete C.V. Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND...........................................................................................................................................................................................................3 EMPLOYMENT HISTORY................................................................................................................................................................................................................................3 CURRENT FIELDS OF INTEREST...........................................................................................................................................................................................................3 I. TEACHING ..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................4 A. Courses Taught........................................................................................................................................................................................................................4 -

The Changing Shape of the Computing World

Outside the Box — The Changing Shape of the Computing World Steve Cunningham Computer Science California State University Stanislaus Turlock, CA 95382 [email protected] http://www.cs.csustan.edu/~rsc Something happened to computing while many of us were busy practicing or teaching our craft, and computing is not quite the same thing we learned. We can ignore this change and others will take our place and teach about it, but they will not have the context and the skill to understand the technology behind it and to carry it forward to the success it should have. And if others carry that torch, computer science will be stunted because we didn't recognize and respond to the opportunity. What happened? Simply this—that Xerox and Apple and, yes, Microsoft opened up the box labeled “CAUTION: Computer Inside” and let the user into the computing picture. Users responded hesitantly but increasingly eagerly and now expect the computer to work for them instead of their working for the computer. Every application now in wide use, and any system that supports a general market, has evolved to meet that expectation. Any computing education that does not pay attention to the user’s role in computing is missing the most vibrant and exciting part of computing today. As it says at the top of this page, you are reading an editorial, not an academic paper. As an editorial, this note represents my personal passion and commitment to the user communication part of computing that the “official” computing establishment has long discounted, and I appreciate John Impagliazzo’s offer of this forum to make my case that computer science is missing the boat in not understanding the need to reshape computer science education to fill this void. -

Webwords 58 Internet Resources Caroline Bowen

Shaping innovative services: Reflecting on current and future practice Webwords 58 Internet resources Caroline Bowen ow timely it was that, just as Webwords’ minder Although they are time-consuming to master, email and completed an entry (Bowen, in press) in Jack Damico the web require of the user little, if any, technical savvy, Hand Martin Ball’s massive, 4-volume encyclopaedia, beyond conquering computer use with a desktop, laptop, intended for students of human communication sciences tablet, or smart phone. The device, must have: (a) a current, and disorders and the “educated general reader”, the topic routinely updated operating system (e.g., iOS, Linux, for the July 2017 JCPSLP landed, somewhat belatedly, on Windows), (b) an up-to-date browser (e.g., Chrome, Firefox, her desk. The topic, “Shaping innovative services: Opera, Safari), (c) plug-ins or browser extensions (e.g., Reflecting on current and future practice”, harmonised Adobe Flash Player, Java applet, QuickTime Player); an perfectly with the encyclopaedia essay, which covered both email client (e.g., Apple Mail, IBM Lotus Notes, MS Outlook, internet innovations, and online resources that have existed Mozilla Thunderbird) and/or (d) browser accessible web since the www was initiated. Accordingly, Webwords 58 mail; and, for mobile computing, (e) access to WiFi or a comprises the complete entry, reproduced here, prior to G3 or G4 network. Mobile computing technology employs publication, by kind permission of the publisher, in the hope Bluetooth, near field communication (NFC), or WiFi, and that SLP/SLT students around the world will find it helpful. mobile hardware, to transmit data, voice and video via a Typically for encyclopaedias, the piece does not include computer or any other wireless-enabled device, without parenthetical citations of published works. -

The People Who Invented the Internet Source: Wikipedia's History of the Internet

The People Who Invented the Internet Source: Wikipedia's History of the Internet PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Sat, 22 Sep 2012 02:49:54 UTC Contents Articles History of the Internet 1 Barry Appelman 26 Paul Baran 28 Vint Cerf 33 Danny Cohen (engineer) 41 David D. Clark 44 Steve Crocker 45 Donald Davies 47 Douglas Engelbart 49 Charles M. Herzfeld 56 Internet Engineering Task Force 58 Bob Kahn 61 Peter T. Kirstein 65 Leonard Kleinrock 66 John Klensin 70 J. C. R. Licklider 71 Jon Postel 77 Louis Pouzin 80 Lawrence Roberts (scientist) 81 John Romkey 84 Ivan Sutherland 85 Robert Taylor (computer scientist) 89 Ray Tomlinson 92 Oleg Vishnepolsky 94 Phil Zimmermann 96 References Article Sources and Contributors 99 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 102 Article Licenses License 103 History of the Internet 1 History of the Internet The history of the Internet began with the development of electronic computers in the 1950s. This began with point-to-point communication between mainframe computers and terminals, expanded to point-to-point connections between computers and then early research into packet switching. Packet switched networks such as ARPANET, Mark I at NPL in the UK, CYCLADES, Merit Network, Tymnet, and Telenet, were developed in the late 1960s and early 1970s using a variety of protocols. The ARPANET in particular led to the development of protocols for internetworking, where multiple separate networks could be joined together into a network of networks. In 1982 the Internet Protocol Suite (TCP/IP) was standardized and the concept of a world-wide network of fully interconnected TCP/IP networks called the Internet was introduced. -

Die Multiple Identität Der Technik

Kirstin Lenzen Die multiple Identität der Technik | Band 9 Editorial Moderne Gesellschaften sind nur zu begreifen, wenn Technik und Körper konzeptu- ell einbezogen werden. Erst in diesen Materialitäten haben Handlungen einen fes- ten Ort, gewinnen soziale Praktiken und Interaktionen an Dauer und Ausdehnung. Techniken und Körper hingegen ohne gesellschaftliche Praktiken zu beschreiben – seien es diejenigen des experimentellen Herstellens, des instrumentellen Handelns oder des spielerischen Umgangs –, bedeutete den Verzicht auf das sozialtheoreti- sche Erbe von Marx bis Plessner und von Mead bis Foucault sowie den Verlust der kritischen Distanz zu Strategien der Kontrolle und Strukturen der Macht. Die biowissenschaftliche Technisierung des Körpers und die Computer-, Nano- und Netzrevolutionen des Technischen führen diese beiden materiellen Dimensionen des Sozialen nunmehr so eng zusammen, dass Körper und Technik als »sozio-orga- nisch-technische« Hybrid-Konstellationen analysierbar werden. Damit gewinnt aber auch die Frage nach der modernen Gesellschaft an Kompliziertheit: die Grenzen des Sozialen ziehen sich quer durch die Trias Mensch – Tier – Maschine und müssen neu vermessen werden. Die Reihe Technik | Körper | Gesellschaft stellt Studien vor, die sich dieser Frage nach den neuen Grenzziehungen und Interaktionsgeflechten des Sozialen annä- hern. Sie machen dabei den technischen Wandel und die Wirkung hybrider Kon- stellationen, die Prozesse der Innovation und die Inszenierung der Beziehungen zwischen Technik und Gesellschaft und/oder Körper und Gesellschaft zum Thema und denken soziale Praktiken und die Materialitäten von Techniken und Körpern konsequent zusammen. Die Reihe wird herausgegeben von Gesa Lindemann und Werner Rammert. Kirstin Lenzen (Dr.), geb. 1972, forschte als Arbeitswissenschaftlerin am Lehrstuhl und Institut für Arbeitswissenschaft (IAW) der RWTH Aachen sowie als Technik- soziologin an den Instituten für Soziologie der RWTH Aachen und der TU Berlin, wo sie bei Werner Rammert promovierte. -

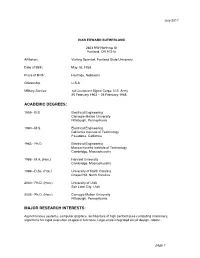

Ivan Sutherland

July 2017 IVAN EDWARD SUTHERLAND 2623 NW Northrup St Portland, OR 97210 Affiliation: Visiting Scientist, Portland State University Date of Birth: May 16, 1938 Place of Birth: Hastings, Nebraska Citizenship: U.S.A. Military Service: 1st Lieutenant Signal Corps, U.S. Army 25 February 1963 – 25 February 1965 ACADEMIC DEGREES: 1959 - B.S. Electrical Engineering Carnegie-Mellon University Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 1960 - M.S. Electrical Engineering California Institute of Technology Pasadena, California 1963 - Ph.D. Electrical Engineering Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts 1966 - M.A. (Hon.) Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts 1986 - D.Sc. (Hon.) University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, North Carolina 2000 - Ph.D. (Hon.) University of Utah Salt Lake City, Utah 2003 - Ph.D. (Hon.) Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania MAJOR RESEARCH INTERESTS: Asynchronous systems, computer graphics, architecture of high performance computing machinery, algorithms for rapid execution of special functions, large-scale integrated circuit design, robots. page 1 EXPERIENCE: 2009 - present Visiting Scientist in ECE Department, Co-Founder of the Asynchronous Research Center, Maseeh College of Engineering and Computer Science, Portland State University 2012 - present Consultant to US Gov’t, Part time ForrestHunt, Inc. 2009 - present Consultant, Part time Oracle Laboratory 2005 - 2007 Visiting Scientist in CSEE Department University of California, Berkeley 1991 - 2009 Vice President and Fellow Sun Microsystems Laboratories