Caught the Cunent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} During My Time Florence Edenshaw Davidson a Haida Woman by Margaret B

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} During My Time Florence Edenshaw Davidson a Haida Woman by Margaret B. Blackman During My Time: Florence Edenshaw Davidson a Haida Woman by Margaret B. Blackman. Our systems have detected unusual traffic activity from your network. Please complete this reCAPTCHA to demonstrate that it's you making the requests and not a robot. If you are having trouble seeing or completing this challenge, this page may help. If you continue to experience issues, you can contact JSTOR support. Block Reference: #dfc8c240-ce25-11eb-8500-eb50c70172de VID: #(null) IP: 116.202.236.252 Date and time: Tue, 15 Jun 2021 22:06:02 GMT. “During My Time” A Haida Woman – Margaret B. Blackman. Margaret Blackman composes a remarkable life history of Florence Davidson on the book ‘ During My Time: Florence Edenshaw Davidson’. Davidson is an indigenous Haida woman from the village Masset that is now formally known as Queen Charlotte Islands that is located in the Northwest coast of Canada. As the book During My Time emphases the Haida villages during the late 19 th century, Blackman interviewed Davidson in the confined of Davidson’s kitchen and front room that Blackman taped 45 hours during the time of 1977 of the “life cycle, economics and division of labour, ceremonial activities and specialist roles” (Stearns, 1985), as the two build their friendship. The well-respected native woman was born in 1896, raised from in the big family whereas she was the ninth child born; her father was a famous woodcarver Charles Edenshaw. The ethnography is written in an indigenous female view of the life of Florence Davidson and those that influence her throughout her time, it also touches on topics such as acculturation throughout the book. -

Bill Reid Gallery Re-Opens ANd Commemorates 100Th Anniversary of One of Canada's Most Renowned Indigenous Artists In

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE June 9, 2020 Bill Reid Gallery Re-opens and Commemorates 100th Anniversary of One of Canada’s Most Renowned Indigenous Artists in – To Speak With a Golden Voice – Exhibition brings fresh perspective to Bill Reid’s legacy with rarely seen artworks and new commissions by Northwest Coast artists inspired by his life and practice VANCOUVER, BC — Bill Reid Gallery of Northwest Coast Art re-opens the gallery and celebrates the milestone centennial birthday of Bill Reid (1920–1998) with an exhibition about his extraordinary life and legacy, To Speak With a Golden Voice, from July 16, 2020 to April 11, 2021. Guest curated by Gwaai Edenshaw — considered to be Reid’s last apprentice — the group exhibition includes rarely seen treasures by Reid and works from artists such as Robert Davidson and Beau Dick. Tracing the iconic Haida artist’s lasting influence, two new artworks by contemporary artist Cori Savard (Haida) and singer-songwriter Kinnie Starr (Mohawk/Dutch/German//Irish) will be created for this highly anticipated exhibition. “Bill Reid was a master goldsmith, sculptor, community activist, and mentor whose lasting legacy and influence has been cemented by his fusion of Haida traditions with his own modernist aesthetic,” says Edenshaw. “Just about every Northwest Coast artist working today has a connection or link to Reid. Before he became renowned for his artwork, he was a CBC radio announcer recognized for his memorable voice — in fact, one of Reid’s many Haida names was Kihlguulins, or ‘golden voice.’ His role as a public figure helped him become a pivotal force in the resurgence of Northwest Coast art, introducing the world to its importance and empowering generations of artists.” Reid was born in Victoria, BC, to a Haida mother and an American father with Scottish-German roots. -

A Haida Manga

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Kateřina Cvachová Indigenous Graphic Novel: Red: A Haida Manga Master’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. Martina Horáková, Ph.D. 2019 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature Acknowledgement I would like to thank Mgr. Martina Horáková, Ph.D. for her guidance during the time I was working on this thesis. Special thanks belong to Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas for his kind and generous offer to help and answer questions regarding his work and for his permission to use his work in my thesis. Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1 Manga and Western Comics ...................................................................................................... 5 The Background of Manga ..................................................................................................... 5 Manga and Comics Terminology ......................................................................................... 13 Sequential Art .................................................................................................................... 15 Time and Space in Comics ............................................................................................... 16 Panels................................................................................................................................. -

Newsletter March 2020

NEWSLETTER MARCH 2020 A new outreach booklet by the Metlakatla Nation offers a step-by-step guide NEW for First Nations that want to measure the full impact of development on their STEP-BY-STEP communities through Cumulative Effects Management (CEM). Metlakatla Cumulative Effects Management: Methods, Results and Future CEM GUIDE FOR Direction of a First Nation-led CEM Program was launched at the Indigenous FIRST NATIONS Forum on Cumulative Effects in Calgary, February 4-6. In 2014, northwest British Columbia was awash in LNG referrals and proposals. The Metlakatla First Nations responded through its Governing Council by establishing a cumulative effects management program. The Council directed the Metlakatla Stewardship Society (MSS) to undertake an Indigenous-informed approach to the work. MSS Executive Director Ross Wilson says leadership wanted to understand the full extent of oil and gas industry benefits and impacts to the community, rather than examining them one by one. “We weren’t talking about one pipeline and one facility, there were numerous pipelines and facility referrals submitted,” explains Wilson. “It was leadership’s directive that established the CEM initiative.” There was limited cumulative effects work being done on the North Coast at the time and few examples of implementing CEM in an Indigenous context. With funding from project proponents and MITACS, Metlakatla and Simon Fraser University’s School of Resource and Environmental Management (REM) partnered to establish an “Indigenous Cumulative Effects” approach. “As a department, we wanted to know what the community values were. How those values might be impacted by industrial activities. And how could we monitor those impacts and provide management approaches,” Wilson explains. -

A Fine Day in Masset: Christopher Auchter Revisits Crucial Moment in Haida Renaissance

NOW IS THE TIME A Fine Day in Masset: Christopher Auchter Revisits Crucial Moment in Haida Renaissance By Philip Lewis August 13, 2019 It was a fine day in Masset: August 22, 1969. For the first time in living memory, a traditional totem pole was being raised in the community. Surrounded by their extended families, members of the Eagle and Raven Clans formed parallel teams to leverage the towering structure into place alongside the old church where it still stands to this day. A NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA PRODUCTION NOW IS THE TIME A NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA PRODUCTION NOW IS THE TIME Elders would speak of “a forest of totem poles,” recalling a time when the giant carvings were common throughout the Haida Gwaii archipelago, but by the late 1960s most had vanished — suppressed by Christian missionaries and assimilationist laws that aimed explicitly to eradicate Indigenous identity from the Canadian landscape. The new pole was the brainchild of Robert Davidson, also known by his Haida name, Guud San Glans, a visionary young artist who would reinvigorate the tradition, becoming a central figure in a vibrant Haida renaissance. While previous generations had kept Haida art alive with small-scale wooden and argillite carvings, Davidson was working a monumental scale that had not been seen in almost a century. Twenty-two-year-old Robert Davidson and his grandfather, Tsinii Robert. Hardly out of his teens at the time, Davidson and his project were the subject of a short NFB doc, released in 1970, called This Was the Time. But the film raised more questions than it answered, presenting events through the muddled lens of the dominant Euro-Canadian culture. -

The University of Chicago Unsettling Futures: Haida

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO UNSETTLING FUTURES: HAIDA FUTURE-MAKING, POLITICS AND MOBILITY IN THE SETTLER COLONIAL PRESENT A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY BY JOSEPH J.Z. WEISS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS DECEMBER 2015 To Hilary Table of Contents Table of Figures ............................................................................................................................. iv Acknowledgments........................................................................................................................... v Chapter 1: An Introduction to Haida Future-Making in Old Massett ............................................. 1 Part 1: Home Chapter 2: Coming Home to Haida Gwaii: Haida Departures and Returns in the Future- Perfect ...................................................................................................................................... 52 Chapter 3: Of Hippies and Haida: Fantasy, Future-Making, and the Alluring Power of Haida Gwaii ............................................................................................................................................. 93 Transition .................................................................................................................................... 136 Part 2: Care Chapter 4: Leading “from the Bottom of the Pole:” Care and Governance in the Haida World 138 Chapter 5: Precarious Authority: Arendt, Endangerment and Environmental -

Xwelíqwiya: the Life of a Stó:Lō Matriarch Rena Point Bolton and Richard Daly Xwelíqwiya

Xwelíqwiya Our Lives: Diary, Memoir, and Letters SERIES EDITOR: JANICE DICKIN Social history contests the construction of the past as the story of elites — a grand narrative dedicated to the actions of those in power. Our Lives seeks instead to make available voices from the past that might otherwise remain unheard. By fore- grounding the experience of ordinary individuals, the series aims to demonstrate that history is ultimately the story of our lives, lives constituted in part by our response to the issues and events of the era into which we are born. Many of the voices in the series thus speak in the context of political and social events of the sort about which historians have traditionally written. What they have to say fills in the details, creating a richly varied portrait that celebrates the concrete, allowing broader historical settings to emerge between the lines. The series invites materials that are engagingly written and that contribute in some way to our understanding of the relationship between the individual and the collective. Manuscripts that include an introduction or epilogue that contextualizes the primary materials and reflects on their significance will be preferred. SERIES TITLES A Very Capable Life: The Autobiography of Zarah Petri John Leigh Walters Letters from the Lost: A Memoir of Discovery Helen Waldstein Wilkes A Woman of Valour: The Biography of Marie-Louise Bouchard Labelle Claire Trépanier Man Proposes, God Disposes: Recollections of a French Pioneer Pierre Maturié, translated by Vivien Bosley Xwelíqwiya: -

Xaad Kilang T'alang Dagwiieehldang

Xaad Kilang T’alang Dagwiieehldang - Strengthening Our Haida Voice by Lucy Bell, Sdaahl K’awaas Bachelor of Arts, the University of British Columbia, 1999 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN INDIGENOUS LANGUAGE REVITALIZATION In the Department of Indigenous Education and the Department of Linguistics © Lucy Bell, 2016 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Xaad Kilang T’alang Dagwiieehldang - Strengthening Our Haida Voice by Lucy Bell Bachelor of Arts, from University of British Columbia, 1999 Supervisory Committee Dr. Su Urbanzyck, Department of Linguistics Supervisor Dr. Marianne Ignace, Department of Linguistics, Simon Fraser University Outside Member iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Su Urbanzyck, Department of Linguistics Supervisor Dr. Marianne Ignace, Departments of Linguistics and First Nations Studies, Simon Fraser University Outside Member The Haida language, Xaad Kil is dangerously close to extinction. The purpose of this study is to find out what traditional Haida foods, medicines, rituals, ceremonies and supernatural beings could revitalize the language. Drawing on archival literature and community interviews, I found almost 100 traditional ways to revitalize Xaad Kil. This study is significant because it shows that the language revitalization answers are within the Haida community and within the Haida culture. In this study, there are two dozen tradition foods, including foods with supernatural connections that support a healthy lifestyle for Haida language speakers. There are also two dozen traditional medicines that could heal the Haida language and the speaker and strengthen their connection to the supernatural world. -

Miniaturisation: a Study of a Material Culture Practice Among the Indigenous Peoples of the Pacific Northwest

Miniaturisation: a study of a material culture practice among the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest John William Davy Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), Department of Anthropology, University College London (UCL), through a Collaborative Doctoral Award partnership with The British Museum. Submitted December, 2016 Corrected May, 2017 94,297 words Declaration I, John William Davy, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where material has been derived from other sources I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. John William Davy, December 2016 i ii Table of Contents Abstract 1 Introduction 3 Research questions 4 Thesis structure 6 Chapter 1: Theoretical frameworks 9 Theories of miniaturisation 13 Semiotics of miniaturisation 17 Elements of miniaturisation 21 Mimesis 22 Scaling 27 Simplification 31 Miniatures in circulation 34 Authenticity and Northwest Coast art 37 Summary 42 Chapter 2: Methodology 43 Museum ethnography 44 Documentary research 51 Indigenous ethnography 53 Assessment of fieldwork 64 Summary 73 Chapter 3: The Northwest Coast 75 History 75 Peoples 81 Social structures 84 Environment 86 iii Material Culture 90 Material culture typologies 95 Summary 104 Chapter 4: Pedagogy and process: Miniaturisation among the Makah 105 The Makah 107 Whaling 109 Nineteenth-century miniaturisation 113 Commercial imperatives 117 Cultural continuity and the Makah 121 Analysing Makah miniatures 123 Miniatures as pedagogical and communicative actors 129 Chapter 5: The Haida string: -

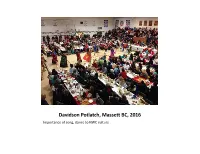

Class 5 Haida

Davidson Potlatch, Massett BC, 2016 Importance of song, dance to NWC culture Today Next Tuesday’s visit to the Canadian Museum of History Haida Art The Great Box Project Haida Gwaii: Graham Island & Moresby Island Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve, Skidegate, Masset, Rose Point (NE corner) Formline elements in Northern NWC art Taken from Hilary Stewart’s book, Looking at Northwest Coast Indian Art, 1979 Thunderbird Ovoids Tension – top edge is sprung upwards as though from pressure, lower edge bulges up caused by downward & inward pull of 2 lower corners. Shape varies. Used as head of creature or human, eye socket, major joints, wing shape, tail, fluke or fin. Small ovoids: for faces, ears, to fill empty spaces & corners. U-forms & S-forms Large U-forms used as: body of bird or animal and feathers Small: fill in open spaces. Kwakwaka’wakw use for small feathers S-forms: part of leg or arm or outline or ribcage Split U-forms Bill Reid, Haida Dogfish See: Strong form line, U forms, split U forms, ovoids compressed into circles Also crescents, teeth, tri-negs… Diverse eyes with eyelids Both eyeball and eyelid are usually placed within an ovoid representing the socket From top to bottom: nose variations, animal ears, eyebrows, tongues, protruding tongues Frontal and profile faces, hands Nose – usually broad & flaring. Ears – U form on top sides of head (humans – no ears). Hands – graceful, stemming from ovoid. Also a symbol for hand-crafted. Claws, legs, feet, arms Hands, flippers & claws usually substantial but arms & legs are often minimal and difficult to locate. -

The Speaking Landscape and Multicultural Memory in Haida Gwaii Fiction: a Bioregional Analysis Kateøina Prajznerová Masaryk University Brno Czech Republic

The Speaking Landscape and Multicultural Memory in Haida Gwaii Fiction: A Bioregional Analysis Kateøina Prajznerová Masaryk University Brno Czech Republic The Speaking Landscape and Multicultural Memory in Haida Gwaii Fiction: A Bioregional Analysis Haida Gwaii, situated off the central West Coast, are also known as the Islands of the People, the Islands at the Boundary of the World, and the Queen Charlotte Islands. To date this remote region has inspired three significant fictional portraits of its complex history: Christie Harris’s Raven’s Cry (1966), Emily Carr’s Klee Wyck (1941) and Amanda Hale’s Sounding the Blood (2001). Each of these non-Haida authors has based her imaginative journey into the Haida Gwaii past on her personal experience of the place, on her conversations with the locals, and on meticulous research of available archival documents. Despite their generational and generic differences, the three women’s responses to the “magical landscape where extraordinary things happened” share several striking characteristics (Hale, 2004). When viewed together, Harris’s, Carr’s, and Hale’s fiction offers a record of the natural as well as cultural history of Haida Gwaii from precontact times to the present. While paying a tribute to the rugged beauty of the Raincoast landscape, it exposes the ruthless exploitation of the islands’ resources. Simultaneously, it testifies to the inescapable voices of multicultural memory inscribed in the Haida Gwaii world. The central connecting point among the three texts as well as the basic frame of this essay is the shaping influence of the Haida Gwaii bioregion. As Sale Kirkpatrick points out, the planet Earth consists of numerous natural areas that are characterized by “particular attributes of flora, fauna, water, climate, soils, and landforms, and by the human settlements and cultures those attributes have given rise to” (Sale, 55). -

The Gund Collection: Contemporary and Historical Art from the Northwest Coast

The Gund Collection: Contemporary and Historical Art from the Northwest Coast and Next: Christos Dikeakos Robert Davidson Christos Dikeakos Red Tailed Eagle Feathers, 1997 The Collector, 2013 alder, acrylic paint, horse hair, opercula ink-jet print From the Collection of George Gund III Private collection, West Vancouver TEACHER’S STUDY GUIDE Fall 2015 Contents Program Information and Goals ................................................................................................................. 3 Background to the Exhibition The Gund Collection: Contemporary and Historical Art from the Northwest Coast .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Background to the Exhibition Next: Christos Dikeakos ............................................................................. 4 Artists’ Background ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Northwest Coast Art: A Brief Introduction .................................................................................................. 7 Pre- and Post-Visit Activities 1. Connecting the Artists ............................................................................................................. 9 Artist Information Sheet ........................................................................................................ 10 Student Worksheet ...............................................................................................................