Presented at the Mccord Museum from April 29 to October 22, 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Reid Gallery Re-Opens ANd Commemorates 100Th Anniversary of One of Canada's Most Renowned Indigenous Artists In

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE June 9, 2020 Bill Reid Gallery Re-opens and Commemorates 100th Anniversary of One of Canada’s Most Renowned Indigenous Artists in – To Speak With a Golden Voice – Exhibition brings fresh perspective to Bill Reid’s legacy with rarely seen artworks and new commissions by Northwest Coast artists inspired by his life and practice VANCOUVER, BC — Bill Reid Gallery of Northwest Coast Art re-opens the gallery and celebrates the milestone centennial birthday of Bill Reid (1920–1998) with an exhibition about his extraordinary life and legacy, To Speak With a Golden Voice, from July 16, 2020 to April 11, 2021. Guest curated by Gwaai Edenshaw — considered to be Reid’s last apprentice — the group exhibition includes rarely seen treasures by Reid and works from artists such as Robert Davidson and Beau Dick. Tracing the iconic Haida artist’s lasting influence, two new artworks by contemporary artist Cori Savard (Haida) and singer-songwriter Kinnie Starr (Mohawk/Dutch/German//Irish) will be created for this highly anticipated exhibition. “Bill Reid was a master goldsmith, sculptor, community activist, and mentor whose lasting legacy and influence has been cemented by his fusion of Haida traditions with his own modernist aesthetic,” says Edenshaw. “Just about every Northwest Coast artist working today has a connection or link to Reid. Before he became renowned for his artwork, he was a CBC radio announcer recognized for his memorable voice — in fact, one of Reid’s many Haida names was Kihlguulins, or ‘golden voice.’ His role as a public figure helped him become a pivotal force in the resurgence of Northwest Coast art, introducing the world to its importance and empowering generations of artists.” Reid was born in Victoria, BC, to a Haida mother and an American father with Scottish-German roots. -

A Haida Manga

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Kateřina Cvachová Indigenous Graphic Novel: Red: A Haida Manga Master’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. Martina Horáková, Ph.D. 2019 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature Acknowledgement I would like to thank Mgr. Martina Horáková, Ph.D. for her guidance during the time I was working on this thesis. Special thanks belong to Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas for his kind and generous offer to help and answer questions regarding his work and for his permission to use his work in my thesis. Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1 Manga and Western Comics ...................................................................................................... 5 The Background of Manga ..................................................................................................... 5 Manga and Comics Terminology ......................................................................................... 13 Sequential Art .................................................................................................................... 15 Time and Space in Comics ............................................................................................... 16 Panels................................................................................................................................. -

A Fine Day in Masset: Christopher Auchter Revisits Crucial Moment in Haida Renaissance

NOW IS THE TIME A Fine Day in Masset: Christopher Auchter Revisits Crucial Moment in Haida Renaissance By Philip Lewis August 13, 2019 It was a fine day in Masset: August 22, 1969. For the first time in living memory, a traditional totem pole was being raised in the community. Surrounded by their extended families, members of the Eagle and Raven Clans formed parallel teams to leverage the towering structure into place alongside the old church where it still stands to this day. A NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA PRODUCTION NOW IS THE TIME A NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA PRODUCTION NOW IS THE TIME Elders would speak of “a forest of totem poles,” recalling a time when the giant carvings were common throughout the Haida Gwaii archipelago, but by the late 1960s most had vanished — suppressed by Christian missionaries and assimilationist laws that aimed explicitly to eradicate Indigenous identity from the Canadian landscape. The new pole was the brainchild of Robert Davidson, also known by his Haida name, Guud San Glans, a visionary young artist who would reinvigorate the tradition, becoming a central figure in a vibrant Haida renaissance. While previous generations had kept Haida art alive with small-scale wooden and argillite carvings, Davidson was working a monumental scale that had not been seen in almost a century. Twenty-two-year-old Robert Davidson and his grandfather, Tsinii Robert. Hardly out of his teens at the time, Davidson and his project were the subject of a short NFB doc, released in 1970, called This Was the Time. But the film raised more questions than it answered, presenting events through the muddled lens of the dominant Euro-Canadian culture. -

Miniaturisation: a Study of a Material Culture Practice Among the Indigenous Peoples of the Pacific Northwest

Miniaturisation: a study of a material culture practice among the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest John William Davy Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), Department of Anthropology, University College London (UCL), through a Collaborative Doctoral Award partnership with The British Museum. Submitted December, 2016 Corrected May, 2017 94,297 words Declaration I, John William Davy, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where material has been derived from other sources I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. John William Davy, December 2016 i ii Table of Contents Abstract 1 Introduction 3 Research questions 4 Thesis structure 6 Chapter 1: Theoretical frameworks 9 Theories of miniaturisation 13 Semiotics of miniaturisation 17 Elements of miniaturisation 21 Mimesis 22 Scaling 27 Simplification 31 Miniatures in circulation 34 Authenticity and Northwest Coast art 37 Summary 42 Chapter 2: Methodology 43 Museum ethnography 44 Documentary research 51 Indigenous ethnography 53 Assessment of fieldwork 64 Summary 73 Chapter 3: The Northwest Coast 75 History 75 Peoples 81 Social structures 84 Environment 86 iii Material Culture 90 Material culture typologies 95 Summary 104 Chapter 4: Pedagogy and process: Miniaturisation among the Makah 105 The Makah 107 Whaling 109 Nineteenth-century miniaturisation 113 Commercial imperatives 117 Cultural continuity and the Makah 121 Analysing Makah miniatures 123 Miniatures as pedagogical and communicative actors 129 Chapter 5: The Haida string: -

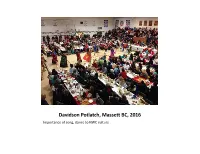

Class 5 Haida

Davidson Potlatch, Massett BC, 2016 Importance of song, dance to NWC culture Today Next Tuesday’s visit to the Canadian Museum of History Haida Art The Great Box Project Haida Gwaii: Graham Island & Moresby Island Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve, Skidegate, Masset, Rose Point (NE corner) Formline elements in Northern NWC art Taken from Hilary Stewart’s book, Looking at Northwest Coast Indian Art, 1979 Thunderbird Ovoids Tension – top edge is sprung upwards as though from pressure, lower edge bulges up caused by downward & inward pull of 2 lower corners. Shape varies. Used as head of creature or human, eye socket, major joints, wing shape, tail, fluke or fin. Small ovoids: for faces, ears, to fill empty spaces & corners. U-forms & S-forms Large U-forms used as: body of bird or animal and feathers Small: fill in open spaces. Kwakwaka’wakw use for small feathers S-forms: part of leg or arm or outline or ribcage Split U-forms Bill Reid, Haida Dogfish See: Strong form line, U forms, split U forms, ovoids compressed into circles Also crescents, teeth, tri-negs… Diverse eyes with eyelids Both eyeball and eyelid are usually placed within an ovoid representing the socket From top to bottom: nose variations, animal ears, eyebrows, tongues, protruding tongues Frontal and profile faces, hands Nose – usually broad & flaring. Ears – U form on top sides of head (humans – no ears). Hands – graceful, stemming from ovoid. Also a symbol for hand-crafted. Claws, legs, feet, arms Hands, flippers & claws usually substantial but arms & legs are often minimal and difficult to locate. -

The Gund Collection: Contemporary and Historical Art from the Northwest Coast

The Gund Collection: Contemporary and Historical Art from the Northwest Coast and Next: Christos Dikeakos Robert Davidson Christos Dikeakos Red Tailed Eagle Feathers, 1997 The Collector, 2013 alder, acrylic paint, horse hair, opercula ink-jet print From the Collection of George Gund III Private collection, West Vancouver TEACHER’S STUDY GUIDE Fall 2015 Contents Program Information and Goals ................................................................................................................. 3 Background to the Exhibition The Gund Collection: Contemporary and Historical Art from the Northwest Coast .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Background to the Exhibition Next: Christos Dikeakos ............................................................................. 4 Artists’ Background ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Northwest Coast Art: A Brief Introduction .................................................................................................. 7 Pre- and Post-Visit Activities 1. Connecting the Artists ............................................................................................................. 9 Artist Information Sheet ........................................................................................................ 10 Student Worksheet ............................................................................................................... -

National Energy Board L’Office National De L’Énergie

JOINT REVIEW PANEL FOR THE ENBRIDGE NORTHERN GATEWAY PROJECT COMMISSION D’EXAMEN CONJOINT DU PROJET ENBRIDGE NORTHERN GATEWAY Hearing Order OH-4-2011 Ordonnance d’audience OH-4-2011 Northern Gateway Pipelines Inc. Enbridge Northern Gateway Project Application of 27 May 2010 Demande de Northern Gateway Pipelines Inc. du 27 mai 2010 relative au projet Enbridge Northern Gateway VOLUME 22 (Revised) Hearing held at Audience tenue à Old Massett Community Hall 348 Eagle Avenue Old Massett, British Columbia February 28, 2012 Le 28 février 2012 International Reporting Inc. Ottawa, Ontario (613) 748-6043 © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada 2012 © Sa Majesté du Chef du Canada 2012 as represented by the Minister of the Environment représentée par le Ministre de l’Environnement et and the National Energy Board l’Office national de l’énergie This publication is the recorded verbatim transcript Cette publication est un compte rendu textuel des and, as such, is taped and transcribed in either of the délibérations et, en tant que tel, est enregistrée et official languages, depending on the languages transcrite dans l’une ou l’autre des deux langues spoken by the participant at the public hearing. officielles, compte tenu de la langue utilisée par le participant à l’audience publique. Printed in Canada Imprimé au Canada HEARING /AUDIENCE OH-4-2011 IN THE MATTER OF an application filed by the Northern Gateway Pipelines Limited Partnership for a Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity pursuant to section 52 of the National Energy Board Act, for authorization to construct and operate the Enbridge Northern Gateway Project. -

Dissertação Apresentada Para Cumprimento Dos Requisitos Necessários À Obtenção Do Grau De Mestre Em Arqueologia, Realizada Sob a Orientação Científica Do Prof

Dissertação apresentada para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Arqueologia, realizada sob a orientação científica do Prof. Doutor Mário Varela Gomes. Haida Totem Poles: Reflections of a Society Kierstin Doreen Hamilton Abstract The Haida were a First Nations group located on the Northwest Coast of Canada. They were exceptional wood carvers that produced various types of works, the most monumental of which were their totem poles. This dissertation analyses 26 of these open architectural structures, each of which belonged to one of the following five types: frontal, mortuary, memorial, house post, or corner post. Of the representations found on poles, 28 different figures were identified. However, individual poles were found to contain between one and fourteen different figures with frontal poles generally featuring the most. The predominant figures on the inventoried poles proved to be birds, humans, and bears. An iconographic structure of a tripartite character was detected that reflects the religious ideology of the Haida population with birds being featured at the top of the poles, humans in the middle, and bears at the lowest point. It also suggests the possible transition from a hunter-gatherer economy to a food producing economy. KEYWORDS: Haida, totem poles, mythology, Northwest Coast, First Nations Resumo Os Haida foram um grupo das Primeiras Nações que habitaram a costa Noroeste do Canadá. Eram excepcionais escultores de madeira, tendo produzido variados tipos de artefactos, dos quais os totem poles eram os mais monumentais. Na presente dissertação são analisadas 26 dessas estruturas arquitectónicas de exterior, sendo que cada uma delas pertenceria a um dos seguintes cinco tipos: frontal, funerário, memorial, trave- mestra, ou postes de esquina. -

Exhibition Review 373

EXHIBITION REVIEW 373 FROM OUR HANDS Exhibition of Native Crafts Organizer: Anita Aarons Contemporary Art Gallery at Harbourfront, Toronto 1982 Catalogue: Contemporary Art Gallery at Harbourfront, $3.00. For four days in early November the Harbourfront complex in Toronto paid tribute to the rich cultural heritage of Ontario's Woodland Indians. Rene Highway's modern dance troupe launched the festivities with the performance of a new work, and other activities included a sweetgrass burning ceremony, social dancing, storytelling, and sale of native foods and handicrafts. The focal point of these celebrations was the grand opening of 'From Our Hands' -. an exhibition of more than four hundred traditional and contemporary native craft items. Gathered together over the past two years from numerous native com- munities throughout Ontario, (with some spillover from Quebec and upstate New York) the artifacts are in Toronto until early December, after which they will tour major galleries across the province into 1984. A scaled-down version of the show will travel to smaller native centres. After commitments within Ontario are fulfilled, it is hoped that the main exhibit will tour beyond provin- cial and national boundaries before arriving at its permanent home - the newly opened Centre for Indian Art of the National Exhibition Centre in Thunder Bay. Unlike many museum or gallery exhibitions, this one was initiated by the native craftspeople themselves. With the assistance of the Ontario Arts Council, the Ontario Crafts Council, the Native Community Branch of the Ontario Ministry of Citizenship and Culture, and The Art Gallery at Harbourfront, a first-rate presentation of quality crafts was mounted. -

The Management of Social and Symbolic Classification Among the Masset Haida

1 THE CURTAIN WITHIN: THE MANAGEMENT OF SOCIAL AND SYMBOLIC CLASSIFICATION AMONG THE MASSET HAIDA Marianne Boel scher M.A., Georg - August - Universitat Gottingen, 1978 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology @ Marianne Boelscher 1985 Simon Fraser University April 1985 All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME : Marianne Bbl scher (Boei scher) DEGREE : Doctor of Phi 1 osophy TITLE OF THESIS: The Curtain Within: The Management of Social and Symbolic Classification among the Masset Haida EXAMINING COMMITTEE: Chairperson: Gary Teeple ARY LEE STEARNS 1SENIOR SUPERVISOR IAN WHITAKER NOEL DYCK WILLIAM W. ELMENDORF EXTERNAL EXAMINER PROFESSOR EMERITUS UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN, MADISON DATE APPROVED : 1/f/fd' PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be a1 lowed without my written permission. -

Caught the Cunent

Caught the cunent Christie Harris, with an introduction by J. Kieran Kealy RCsurnC: Christie Harris prt?sente sa carritre litte'raire, qu 'elle a consacre'e en trEs grande partie & la jeunesse; elle rappelle le r6le de pionniEre qu 'elle a jout? dans la sauvegarde et la recension des lkgendes et des kitsame'rindiens. Introduction Christie Hanis is one of British Columbia's most respected and honoured chil- dren's writers. Though she has written biographies, fictionalized histories, and was in fact, one of Canada's firstfantasists,sheis bestrememberedfor Raven's cry, her award-winning account of the near extinction of Haida culture as a result of the European invasion of the late eighteenth century, and her seven collections of West Coast Native legends, particularly her highly celebratedblouse Woman stories, the first of which, Mouse Woman and the vanishedprincesses, won Ms. Hanis her second Canadian Library Association Book of the Year award. The following paper, previously unpublished, was originally presented at Serendipity 90, avancouver Children's Roundtable/IBBYconference, onMay 18, 1990.In it she examines her career as a writer, focusingparticularlyon her lifelong interest in Native lore. More particularly, she both defends her role as a non-Native collector of Native legends and celebrates recent collections, like those of Kenneth Harris, in which Natives are collecting and publishing their own family stories, stories that she clearly suggests should be c~iisideied"peis~iid pr~peky." Ms. Harris's importancein the history of the dissemination of BC Native culture is perhaps best established by Robert Davidson, a descendent of the tribal chiefs chronicled in Raven's cry, who co-authored the foreword to this recently repub- lished text. -

Northwest Coast Formline Design Definitions and Student Activities

SEALASKA HERITAGE CURRICULUM NORTHWEST COAST FORMLINE DESIGN DEFINITIONS AND STUDENT ACTIVITIES ART KIT TEXTBOOK GRADE LEVEL 5–8 Copyright © Sealaska Heritage Institute All Rights Reserved SEALASKA HERITAGE INSTITUTE 105 S. Seward St. Suite 201 Juneau, Alaska 99801 Tel: (907) 463-4844 Fax: (907) 586-9293 www.sealaskaheritage.org Textbook Design and Layout: Alison Krein, Kathy K’ei Joon Dye, and Nobu Koch Cover Design: Alison Krein Formline Design on Cover: Am’ala: Wil Mangaa da Ha’lidzogat (“Am’ala: He Who Holds Up the Earth”) Shuká Hít house front in the Walter Soboleff Building, by David A. Boxley. The section on the right of the image is part of the artist’s original sketch for this masterpiece. Illustrations: p. 4 “Purpose of the Unit”, p. 5 “Introduction to Formline Design”, pp. 7-9 “Definitions and Vocabulary,” pp. 14-15 “Class Activities: Teacher’s Guide”, pp. 42-47 “Step-by-Step: Assemble a Formline Set” (Feather Design Set and Salmon-Trout Head Design Set), pp. 48-58 “Formline Design Sets,” pp. 29-38 “Flash Cards”: Created by Steve Brown, with graphic layout by Nobu Koch and Alison Krein Illustrations p. 9 “Parts of a Feather” and pp. 39-41 “Step-by-Step: Draw Formline Shapes”: Alison Krein Photographs pp. 19-23 “Formline Design Examples”, p. 24 “Feather and Wing Design Examples”, p. 25 “Salmon-Trout Ovoid Examples”, p. 27 “Engraving Examples”: Included with permissions by the owners. Do not copy or distribute any of these photographs without permission by the owners. Editors: Kari Groven, Steve Brown, Annie Calkins, Nancy Lehnhart