Writing Woman with "The Laugh of the Medusa" and Antioedipus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dialectic of Freedom 1St Edition Pdf Free Download

THE DIALECTIC OF FREEDOM 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Maxine Greene | 9780807728970 | | | | | The Dialectic of Freedom 1st edition PDF Book She examines the ways in which the disenfranchised have historically understood and acted on their freedom—or lack of it—in dealing with perceived and real obstacles to expression and empowerment. It offers readers a critical opportunity to reflect on our continuing ideological struggles by examining popular books that have made a difference in educational discourse. Professors: Request an Exam Copy. Major works. Max Horkheimer Theodor W. The latter democratically makes everyone equally into listeners, in order to expose them in authoritarian fashion to the same programs put out by different stations. American Paradox American Quest. Instead the conscious decision of the managing directors executes as results which are more obligatory than the blindest price-mechanisms the old law of value and hence the destiny of capitalism. Forgot your password? There have been two English translations: the first by John Cumming New York: Herder and Herder , ; and a more recent translation, based on the definitive text from Horkheimer's collected works, by Edmund Jephcott Stanford: Stanford University Press, Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. Peter Lang. The truth that they are nothing but business is used as an ideology to legitimize the trash they intentionally produce. Archetypal literary criticism New historicism Technocriticism. The author concludes with suggestions for approaches to teaching and learning that can provoke both educators and students to take initiatives, to transcend limits, and to pursue freedom—not in solitude, but in reciprocity with others, not in privacy, but in a public space. -

10753820.Pdf

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Outside of a Logocentric Discourse? The Case of (Post)modern Czech “Women’s” Writing Jan Matonoha Degree: MPhil Form of Study: Research Department of Slavonic Studies School of Modern Languages and Cultures University of Glasgow May 2007 © Jan Matonoha, 2007 ProQuest Number: 10753820 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10753820 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

Nepali Women Nepali Women

her-047 Fall 2009 v23n2.qxp 9/11/09 12:04 PM Page C1 PINK PANTY THE WOMEN’S FALL OF PROTEST MOVEMENT PATRIARCHY INDIA PUB ATTACK IS THERE ROOM ANGERS WOMEN FOR MEN? IMMINENT WOMEN’S NEWS & FEMINIST VIEWS Fall 2009 Vol. 23 No. 2 Made in Canada AFGHANAFGHAN WOMENWOMEN STAND STRONG AGAINST SHIA LALAWW NEPALINEPALI WOMENWOMEN FIGHTFIGHT FORFOR CONSTITUTIONALCONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTSRIGHTS $6.75 Canada/US Publications Mail Agreement No. 40008866; PAP Registration No. 07944 Return Undeliverable Addresses to: PO Box 128, Winnipeg, MB R3C 2G1 Canada Display until December 15, 2009 her-047 Fall 2009 v23n2.qxp 9/10/09 1:03 PM Page C2 Joss Maclennan Design, CEP Local 591-G Joss Maclennan Design, CEP Local 591-G CAWCAW womenwomen WeWe marchmarch forfor equality. equality. WeWe speakspeak outout for for justice. justice. We fight for change. We fight for change. For more information on women’s Forissues more and information rights please on visit women’s issueswww.caw.ca/women and rights please visit www.caw.ca/women CAW Full Sum-09.indd 1 28/05/09 5:19 PM her-047 Fall 2009 v23n2.qxp 9/11/09 12:05 PM Page 1 FALL 2009 / VOLUME 23 NO. 2 news THE MOTHER OF ALL MUSEUMS 6 by Janet Nicol TEL AVIV SHOOTING IGNITES GAY RIGHTS 7 by Idit Cohen TIANANMEN MOTHERS REFUSE TO FORGET 22: Yvette Nolan 8 by Janet Nicol NEPALI WOMEN DEMAND EQUALITY 9 by Chelsea Jones 12 CAMPAIGN UPDATES PARENTING BILL WOULD ERODE RIGHTS 13 by Pamela Cross features IS FEMINISM MEN’S WORK, TOO? 16 It’s not called the women’s movement for nothing. -

Samhita Mukhopadhyay and Jaclyn Friedman Take the Theory to the Next Level

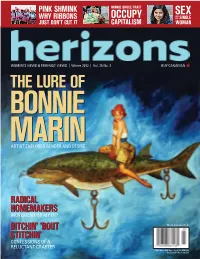

PINK SHMINK MINNIE BRUCE PRATT SEX AND WHY RIBBONS OCCUPY THE SINGLE JUST DON’T CUT IT CAPITALISM WOMAN WOMEN’S NEWS & FEMINIST VIEWS | Winter 2012 | Vol. 25 No. 3 BUY CANADIAN THETHE LURELURE OFOF BONNIEBONNIE MARINMARIN ARTIST EXPLORES GENDER AND DESIRE RADICAL HOMEMAKERS MOVEMENT OR MYTH? BITCHIN’ ’BOUT $6.75 Canada/U.S. STITCHIN’ CONFESSIONS OF A RELUCTANT CRAFTER Publications Mail Agreement No. 40008866; Display until March 30, 2012 CAW Full (bleed) Win-12.indd 1 11-11-28 2:03 PM WINTER 2012 / VOLUME 25 NO. 3 news SEEING RED OVER PINK . 6 by Amanda Le Rougetel CAMPAIGN UPDATES . 8 THE POET VS. THE PROFITEERS AN INTERVIEW WITH MINNIE BRUCE PRATT . 11 by Joy Parks 11 features CONFESSIONS OF A RELUCTANT CRAFTER . .14 The knitting trend has hit Canada by storm. So what’s a feminist to do: Join the rebel fibre movement or cast dire warnings that women will soon be barefoot in the kitchen? by Deborah Ostrovsky BASTARDS AND BULLIES . .20 Dorothy Palmer’s debut novel, When Fenelon Falls, features Jordan, a young girl who is adopted and disabled. The protagonist reflects some of Palmer’s experiences about what it is like to be adopted and disabled. by Niranjana Iyer THE LURE OF BONNIE MARIN: LESSONS IN TRANSGRESSIONS . .24 Visual artist Bonnie Marin freely mixes gender, race and even species in erotic environments that are part middle class 1950s normalcy and part spectacles of perversity. 14 by Shawna Dempsey HOW FEMINISM CAN IMPROVE YOUR SEX LIFE . .28 Two new books about sex and politics paint a provocative picture of feminist dating 45 years after the personal was declared to be political. -

Narrating the Nation of Palestine by Nuzhat Abbas

SPECIAL OFFER FOR CONFERENCE DELEGATES See inside for details • Canada $5.95/US $5.95 • Vol. 16 No.4 • Spring 2003 WOMEN’S NEWS & FEMINIST VIEWS NARRATINGNARRATING THETHE NATIONNATION OFOF PALESTINEPALESTINE AN INTERVIEW WITH NAHLA ABDO WHYWHY DODO LESBIANSLESBIANS BATTER?BATTER? JANICE RISTOCK WANTS TO KNOW THETHE HEARTHEART DOESDOES NOTNOT BENDBEND A CONVERSATION WITH MAKEDA SILVERA NAC NAC. Who’s There? Lisa B. Rundle: Marshalling in the Third Wave Pump up the Volume: Veda Hille, Afua Cooper, Jorane Made in Canada in Made table of contents SPRING 2003 / VOLUME 16 NO. 4 FEATURES NARRATING THE NATION 18 OF PALESTINE Arab feminist Nahla Abdo has written extensively about women and military confrontation and is the founder of a gender research unit within a mental health program in Gaza. A sociology professor at Carleton University, Ms Abdo talks to Herizons about the PLO, Israel, Palestinian women and about her upcoming book, Sexuality, Citizenship and the Nation State: Experiences of Palestinian Women. by Nuzhat Abbas IN CONVERSATION WITH 23 MAKEDA SILVERA Toronto author Makeda Silvera discusses mother- hood, poverty, colonialism and the creative process with author Elizabeth Ruth. “I’ve always questioned the imperial culture’s view of motherhood: mothers are virtuous, mothers are asexual…” by Elizabeth Ruth WHY DO LESBIANS Page 26: Janice Ristock 26 BATTER? A decade ago, Janice Ristock and some colleagues produced a booklet on violence in lesbian relation- NEWS ships. Now the Winnipeg researcher has written a groundbreaking book on the issue. VILLAGERS JOIN CAMPAIGN by Helen Fallding 6 AGAINST FGM A Senegalese women’s organization called Tostan, which means ‘breakthrough’ in the Wolof language, ARTS & LIT sponsors education programs that have influenced the decision of 708 villages to make public declara- CAN LIT tions to abandon the generations-old practice of 32 FICTION female genital mutilation. -

Generic Affinities, Posthumanisms and Science-Fictional Imaginings

GENERIC AFFINITIES, POSTHUMANISMS, SCIENCE-FICTIONAL IMAGININGS SPECULATIVE MATTER: GENERIC AFFINITIES, POSTHUMANISMS AND SCIENCE-FICTIONAL IMAGININGS By LAURA M. WIEBE, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University © Copyright by Laura Wiebe, October 2012 McMaster University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2012) Hamilton, Ontario (English and Cultural Studies) TITLE: Speculative Matter: Generic Affinities, Posthumanisms and Science-Fictional Imaginings AUTHOR: Laura Wiebe, B.A. (University of Waterloo), M.A. (Brock University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Anne Savage NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 277 ii ABSTRACT Amidst the technoscientific ubiquity of the contemporary West (or global North), science fiction has come to seem the most current of genres, the narrative form best equipped to comment on and work through the social, political and ethical quandaries of rapid technoscientific development and the ways in which this development challenges conventional understandings of human identity and rationality. By this framing, the continuing popularity of stories about paranormal phenomena and supernatural entities – on mainstream television, or in print genres such as urban fantasy and paranormal romance – may seem to be a regressive reaction against the authority of and experience of living in technoscientific modernity. Nevertheless, the boundaries of science fiction, as with any genre, are relational rather than fixed, and critical engagements with Western/Northern technoscientific knowledge and practice and modern human identity and being may be found not just in science fiction “proper,” or in the scholarly field of science and technology studies, but also in the related genres of fantasy and paranormal romance. -

The Impact of Digital Feminist Activism by Cassie

#TrendingFeminism: The Impact of Digital Feminist Activism by Cassie Clark B.A. in English and Theatre, May 2007, St. Olaf College A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 17, 2015 Thesis directed by Todd Ramlow Adjunct Professor of Women’s Studies This work is dedicated to my grandfather, who, upon being told that I was planning to attend graduate school, responded, “Good, you should have more education than your father.” ii The author wishes to acknowledge Dr. Todd Ramlow for his expertise, knowledge, and encouragement. She also wishes to acknowledge Dr. Alexander Dent for his invaluable guidance regarding the performance of media and digital technologies. iii Abstract of Thesis #TrendingFeminism: The Impact of Digital Feminist Activism As the use of online platforms such as social networking sites, also known as social media, and blogs grew in popularity, feminists began to embrace digital media as a significant space for activism. Digital feminist activism is a new iteration of feminist activism, offering new tools and tactics for feminists to utilize to spread awareness, disseminate information, and mobilize constituents. In this paper I examine the intent, usefulness, and potential impact of digital feminist activism in the United States by analyzing key examples of social movements conducted via digital media. These analyses not only provide useful examples of a variety of digital feminist efforts, they also highlight strengths and weaknesses in each campaign with the aim of improving the impact of future digital feminist campaigns. -

Presentations Introduction Recent Feminist De

Beyond the Generational Line: An Exploration of Feminist Online Sites and Self-(Re)presentations Yi-lin Yu National Ilan University, Taiwan Abstract This article deals with the feminist generation issue by tracing the transition from generational to non-generational thinking in recent feminist discourse on third-wave feminism. Informed by certain feminist recommendations of affording alternative paradigms in place of the oceanic wave metaphor to describe the rela- tionships between different feminists, this study offers the insights gained from an investigation with three feminist online sites, The F Word, Eminism, and Guerrilla Girls, in which these online feminists have participated in building up a third wave consciousness or a third space site through their engagement in (re)presenting their feminist selves and identities. In developing a both/and third wave con- sciousness, these online feminists have bypassed the dualistic understanding of sec- ond and third wave feminism and reached a cross-generational commonality of adhering to feminist ideology and coalition in cyberspace as a third space. Through a content analysis of their online feminist self-(re)presentations, this pa- per concludes by arguing that they have not only reformulated the concept of third wave feminism but also worked toward a new configuration of third space narratives and subjectivities that sheds light on contemporary feminist thinking about feminist genealogy and history. Key words third-wave feminism, feminist generation, feminist online sites, self-(re)presentation Introduction Recent feminist development of third-wave discourses has been bom- barded with a conundrum regarding generational debates. Although 54 ❙ Yi-lin Yu some feminist scholars are preoccupied with using familial metaphors to depict different feminist generations, others have called forth a rethink- ing of the topic in non-generational terms. -

Her-042 Summer 2008 V21n5.Qxp

WOMEN’S CYCLES (MOTORCYCLES, THAT IS) | TACKLING WIFE ABUSE IN AFGHANISTAN | SUMMER READING GUIDE & MORE! WOMEN’S NEWS & FEMINIST VIEWS Summer 2008 Vol. 22 No. 1 Made in Canada JANE RULES THE BELOVED AUTHOR SHARES HER THOUGHTS ON LIVING, LOVING AND WRITING SIZING UP FASHION JANE RULE 1931–2007 ZERO TOLERANCE FOR SIZE ZERO $6.95 Canada/US Publications TOSHI Mail Agreement No. 40008866; PAP Registration No. 07944 Return Undeliverable Addresses to: REAGON PO Box 128, Winnipeg, MB R3C 2G1 Canada FINDING THE GOOD Display until September 15, 2008 WhyIJoinedtheCAW AA Young Young Worker's Worker's Story Story Iusedto ButonceI think my got injured... job was the greatest... Nobody was Things changed when there I joined the CAW... to help... Nowthere'salwayssomeoneinmycorner. Wanna join? Visit: www.caw.ca or call 1-877-495-6551 Email: [email protected] SUMMER 2008 / VOLUME 22 NO. 1 news DOMESTIC ASSAULT IN AFGHANISTAN 6 by Lauryn Oates 8 CAMPAIGN UPDATES MY HEART BELONGS IN THE CAPE 12 by Anat Cohen ITALIAN WOMEN MOBILIZE 13 by Meagan Williams 6: Addressing Domestic Assault in Afghanistan WHAT IF EQUALITY RULED? 14 by Shari Graydon features HOW THE MEDIA KEEPS US HUNG UP 16 ON BODY IMAGE By Shari Graydon JANE RULES 20 It has been said that every child on Galiano learned to swim in Jane Rule and Helen Sonthoff ’s swimming pool. The couple bought their house on Galiano Island as a weekend getaway in the 1970s, fell in love with it and never left. Rule’s legacy is explored in this intimate interview completed in the year before her passing. -

Comprehensive Annotated Listing of All Journals Selected

5. Chang Pilwha. Annotated Listing of All Periodicals Selected7. forISSN Feminist 1225-9276. Periodicals Note: Not every periodical will have table of contents pages reproduced in this issue of Feminist Periodicals. See page 4 for a listing 8. OCLC 33094607. of periodicals in this issue. 9. Alternative Press Index; Current Contents: Social & Behavioral Sciences; IOWA Guide; Social Sciences AFFILIA: JOURNAL OF WOMEN AND SOCIAL WORK Citation Index. 1. 1986. 10. GenderWatch. 2. 4/year. 11. “AJWS is an interdisciplinary journal, publishing articles 3. $129 (indiv. print only), $779 (inst. print only), $716 (inst. pertaining to women’s issues in Asia from a feminist e-access), $795 (inst. combined), $42 (indiv. single print perspective.” issue), $214 (inst. single print issue). 4. Sage Publications, 2455 Teller Rd., Thousand Oaks, CA ASIAN WOMEN 91320 [email: [email protected]] [website: http:// 1. 1995. aff.sagepub.com]. 2. 4/year. 5. Debora Ortega & Noël Busch-Armendariz 3. $60 (student), $80 (indiv.), $120 (inst.). 6. Affilia, Howard University School of Social Work, 601 4. Asian Women, Research Institute of Asian Women, Howard Pl. N.W., Washington DC 20059; book reviews: Sookmyung Women's University, Cheongpa-ro 47gil 100, Dr. Patricia O’Brien [email: [email protected]]. Youngsan-gu, Seoul, 140-742, Korea [email: 7. ISSN 0886-1099. [email protected]] [website: http://riaw.sookmyung. 8. OCLC 12871850. ac.kr]. 9. Criminal justice, family, social science, and women’s 5. So Jin Park studies indexes. Also available on microfilm from Bell & 7. ISSN 1225-925X. Howell Information and Learning, Ann Arbor, MI. 8. OCLC 7673725, 36782501. -

Branching Out: Second-Wave Feminist Periodicals and the Archive of Canadian Women’S Writing Tessa Jordan University of Alberta

Branching Out: Second-Wave Feminist Periodicals and the Archive of Canadian Women’s Writing Tessa Jordan University of Alberta Look, I push feminist articles as much as I can ... I’ve got a certain kind of magazine. It’s not Ms. It’s not Branching Out. It’s not Status of Women News. Doris Anderson Rough Layout hen Edmonton-based Branching Out: Canadian Magazine for WWomen (1973 to 1980) began its thirty-one-issue, seven-year history, Doris Anderson was the most prominent figure in women’s magazine publishing in Canada. Indeed, her work as a journalist, editor, novelist, and women’s rights activist made Anderson one of the most well-known faces of the Canadian women’s movement. She chaired the Canadian Advisory Coun- cil on the Status of Women from 1979 to 1981 and was the president of the National Action Committee on the Status of Women from 1982 to 1984, but she is best known as the long-time editor of Chatelaine, Can- ada’s longest lived mainstream women’s magazine, which celebrated its eightieth anniversary in 2008. As Chatelaine’s editor from 1957 to 1977, she was at the forefront of the Canadian women’s movement, publishing articles and editorials on a wide range of feminist issues, including legal- izing abortion, birth control, divorce laws, violence against women, and ESC 36.2–3 (June/September 2010): 63–90 women in politics. When Anderson passed away in 2007, then Governor- General Adrienne Clarkson declared that “Doris was terribly important as a second-wave feminist because she had the magazine for women and Tessa Jordan (ba it was always thoughtful and always had interesting things in it” (quoted Victoria, ma Alberta) in Martin). -

Adorno's Dialectical Realism

ADORNO’S DIALECTICAL REALISM Linda Martín Alcoff (Hunter College/CUNY Graduate Center) Alireza Shomali (Wheaton College, Massachusetts) The idea that Adorno should be read as a “realist” of any sort may in- deed sound odd. And unpacking from Adorno’s elusive prose a credible and useful normative reconstruction of epistemology and metaphysics will take some work. But we argue that he should be added to the grow- ing group of epistemologists and metaphysicians who have been devel- oping post-positivist versions of realism such as contextual, internal, pragmatic and critical realisms. These latter realisms, however, while helpfully showing how realism can coexist with ontological pluralism, for example, as well as a highly contextualised account of knowledge, have not developed a political reflexivity about how the object of knowledge—the real—is constructed. As a field, then, post-positivist realisms have been politically naïve, which is perhaps why they have not enjoyed more influence among Continental philosophers. Introduction Bruno Latour has recently called for a reconstructive moment in the cri- tiques of science and truth.1 Rather than repeatedly calling out the prob- lems with truth concepts, or critiquing the strategic context within which regimes of truth are produced, Latour argues that the discursive moment in which we find ourselves today requires an ability to make and defend truth claims. Surely he is right that much hangs in the balance concerning ongoing debates about issues such as global warming, the etiology of HIV/AIDS, the cause of the economic collapse, the nature of gender dif- ferences. Surely we can mark out better and worse candidates for truth in regard to these debates, even if capital “T” truth remains fallible.