Wildflowers from East and West by RICHARD E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to the Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- LILIACEAE

Guide to the Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- LILIACEAE LILIACEAE de Jussieu 1789 (Lily Family) (also see AGAVACEAE, ALLIACEAE, ALSTROEMERIACEAE, AMARYLLIDACEAE, ASPARAGACEAE, COLCHICACEAE, HEMEROCALLIDACEAE, HOSTACEAE, HYACINTHACEAE, HYPOXIDACEAE, MELANTHIACEAE, NARTHECIACEAE, RUSCACEAE, SMILACACEAE, THEMIDACEAE, TOFIELDIACEAE) As here interpreted narrowly, the Liliaceae constitutes about 11 genera and 550 species, of the Northern Hemisphere. There has been much recent investigation and re-interpretation of evidence regarding the upper-level taxonomy of the Liliales, with strong suggestions that the broad Liliaceae recognized by Cronquist (1981) is artificial and polyphyletic. Cronquist (1993) himself concurs, at least to a degree: "we still await a comprehensive reorganization of the lilies into several families more comparable to other recognized families of angiosperms." Dahlgren & Clifford (1982) and Dahlgren, Clifford, & Yeo (1985) synthesized an early phase in the modern revolution of monocot taxonomy. Since then, additional research, especially molecular (Duvall et al. 1993, Chase et al. 1993, Bogler & Simpson 1995, and many others), has strongly validated the general lines (and many details) of Dahlgren's arrangement. The most recent synthesis (Kubitzki 1998a) is followed as the basis for familial and generic taxonomy of the lilies and their relatives (see summary below). References: Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (1998, 2003); Tamura in Kubitzki (1998a). Our “liliaceous” genera (members of orders placed in the Lilianae) are therefore divided as shown below, largely following Kubitzki (1998a) and some more recent molecular analyses. ALISMATALES TOFIELDIACEAE: Pleea, Tofieldia. LILIALES ALSTROEMERIACEAE: Alstroemeria COLCHICACEAE: Colchicum, Uvularia. LILIACEAE: Clintonia, Erythronium, Lilium, Medeola, Prosartes, Streptopus, Tricyrtis, Tulipa. MELANTHIACEAE: Amianthium, Anticlea, Chamaelirium, Helonias, Melanthium, Schoenocaulon, Stenanthium, Veratrum, Toxicoscordion, Trillium, Xerophyllum, Zigadenus. -

Fair Use of This PDF File of Herbaceous

Fair Use of this PDF file of Herbaceous Perennials Production: A Guide from Propagation to Marketing, NRAES-93 By Leonard P. Perry Published by NRAES, July 1998 This PDF file is for viewing only. If a paper copy is needed, we encourage you to purchase a copy as described below. Be aware that practices, recommendations, and economic data may have changed since this book was published. Text can be copied. The book, authors, and NRAES should be acknowledged. Here is a sample acknowledgement: ----From Herbaceous Perennials Production: A Guide from Propagation to Marketing, NRAES- 93, by Leonard P. Perry, and published by NRAES (1998).---- No use of the PDF should diminish the marketability of the printed version. This PDF should not be used to make copies of the book for sale or distribution. If you have questions about fair use of this PDF, contact NRAES. Purchasing the Book You can purchase printed copies on NRAES’ secure web site, www.nraes.org, or by calling (607) 255-7654. Quantity discounts are available. NRAES PO Box 4557 Ithaca, NY 14852-4557 Phone: (607) 255-7654 Fax: (607) 254-8770 Email: [email protected] Web: www.nraes.org More information on NRAES is included at the end of this PDF. Acknowledgments This publication is an update and expansion of the 1987 Cornell Guidelines on Perennial Production. Informa- tion in chapter 3 was adapted from a presentation given in March 1996 by John Bartok, professor emeritus of agricultural engineering at the University of Connecticut, at the Connecticut Perennials Shortcourse, and from articles in the Connecticut Greenhouse Newsletter, a publication put out by the Department of Plant Science at the University of Connecticut. -

Download/Empfehlung-Invasive-Arten.Pdf

09-15078 rev FORMAT FOR A PRA RECORD (version 3 of the Decision support scheme for PRA for quarantine pests) European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organisation Organisation Européenne et Méditerranéenne pour la Protection des Plantes Guidelines on Pest Risk Analysis Lignes directrices pour l'analyse du risque phytosanitaire Decision-support scheme for quarantine pests Version N°3 PEST RISK ANALYSIS FOR LYSICHITON AMERICANUS HULTÉN & ST. JOHN (ARACEAE) Pest risk analyst: Revised by the EPPO ad hoc Panel on Invasive Alien Species Stage 1: Initiation The EWG was held on 2009-03-25/27, and was composed of the following experts: - Ms Beate Alberternst, Projektgruppe Biodiversität und Landschaftsökologie ([email protected]) - M. Serge Buholzer, Federal Department of Economic Affairs DEA ([email protected]) - M. Manuel Angel Duenas, CEH Wallingford ([email protected]) - M. Guillaume Fried, LNPV Station de Montpellier, SupAgro ([email protected]), - M. Jonathan Newman, CEH Wallingford ([email protected]), - Ms Gritta Schrader, Julius Kühn Institut (JKI) ([email protected]), - M. Ludwig Triest, Algemene Plantkunde en Natuurbeheer (APNA) ([email protected]) - M. Johan van Valkenburg, Plant Protection Service ([email protected]) 1 What is the reason for performing the Lysichiton americanus originates from the pacific coastal zone of Northwest-America PRA? and was imported into the UK at the beginning of the 20th century as a garden ornamental, and has since been sold in many European countries, including southern 1 09-15078 rev countries like Italy. It is now found in 11 European countries. The species has been observed to reduce biodiversity in the Taunus region in Germany. -

A Preliminary Survey of Plant Distribution in Ohio.* John H

A PRELIMINARY SURVEY OF PLANT DISTRIBUTION IN OHIO.* JOHN H. SCHAFFNER. The following data are presented as a preliminary basis for field work in determining the natural plant areas of Ohio. It is hoped that the botanists of the State will begin active study of local conditions with a view to determine natural or transition boundaries as well as cataloging local associations. The distri- bution lists are based on herbarium material and more than 15 years of sporadic botanizing in the state. Of course, distribution at present indicates to a considerable extent merely the distri- bution of enthusiastic botanists and their favorite collecting grounds. Nevertheless, enough has been done to indicate in a rough way the general character of our plant geography. The kind of data most important in indicating characteristic areas are as follows:— 1. Meteorological data. 2. Geology, including the nature of the surface rock and soil. 3. Physiography and topography. 4. The actual distribution of characteristic species of plants and to some extent of animals. In Ohio, the following important maps may be studied in this connection:— Meteorology. By Otto E. Jennings in Ohio Naturalist 3: 339-345, 403-409, 1903. Maps I-XII. By J. Warren Smith in Bull. Ohio Agr. Exp. Station No. 235, 1912. Figs. 3-14. Geology. By J. A. Bownocker, A Geological Map of Ohio. 1909. Topography. The maps of the topographic survey, not yet completed. Various geological reports. The eastern half of Ohio is a part of the Alleghany Plateau. The western half belongs to the great interior plain. In Ohio, the Alleghany Plateau consists of a northern glaciated region and a southern non-glaciated region. -

Willi Orchids

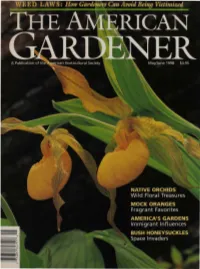

growers of distinctively better plants. Nunured and cared for by hand, each plant is well bred and well fed in our nutrient rich soil- a special blend that makes your garden a healthier, happier, more beautiful place. Look for the Monrovia label at your favorite garden center. For the location nearest you, call toll free l-888-Plant It! From our growing fields to your garden, We care for your plants. ~ MONROVIA~ HORTICULTURAL CRAFTSMEN SINCE 1926 Look for the Monrovia label, call toll free 1-888-Plant It! co n t e n t s Volume 77, Number 3 May/June 1998 DEPARTMENTS Commentary 4 Wild Orchids 28 by Paul Martin Brown Members' Forum 5 A penonal tour ofplaces in N01,th America where Gaura lindheimeri, Victorian illustrators. these native beauties can be seen in the wild. News from AHS 7 Washington, D . C. flower show, book awards. From Boon to Bane 37 by Charles E. Williams Focus 10 Brought over f01' their beautiful flowers and colorful America)s roadside plantings. berries, Eurasian bush honeysuckles have adapted all Offshoots 16 too well to their adopted American homeland. Memories ofgardens past. Mock Oranges 41 Gardeners Information Service 17 by Terry Schwartz Magnolias from seeds, woodies that like wet feet. Classic fragrance and the ongoing development of nell? Mail-Order Explorer 18 cultivars make these old favorites worthy of considera Roslyn)s rhodies and more. tion in today)s gardens. Urban Gardener 20 The Melting Plot: Part II 44 Trial and error in that Toddlin) Town. by Susan Davis Price The influences of African, Asian, and Italian immi Plants and Your Health 24 grants a1'e reflected in the plants and designs found in H eading off headaches with herbs. -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus

STATUS AND PROTECTION OF GLOBALLY THREATENED SPECIES IN THE CAUCASUS CEPF Biodiversity Investments in the Caucasus Hotspot 2004-2009 Edited by Nugzar Zazanashvili and David Mallon Tbilisi 2009 The contents of this book do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of CEPF, WWF, or their sponsoring organizations. Neither the CEPF, WWF nor any other entities thereof, assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product or process disclosed in this book. Citation: Zazanashvili, N. and Mallon, D. (Editors) 2009. Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus. Tbilisi: CEPF, WWF. Contour Ltd., 232 pp. ISBN 978-9941-0-2203-6 Design and printing Contour Ltd. 8, Kargareteli st., 0164 Tbilisi, Georgia December 2009 The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. This book shows the effort of the Caucasus NGOs, experts, scientific institutions and governmental agencies for conserving globally threatened species in the Caucasus: CEPF investments in the region made it possible for the first time to carry out simultaneous assessments of species’ populations at national and regional scales, setting up strategies and developing action plans for their survival, as well as implementation of some urgent conservation measures. Contents Foreword 7 Acknowledgments 8 Introduction CEPF Investment in the Caucasus Hotspot A. W. Tordoff, N. Zazanashvili, M. Bitsadze, K. Manvelyan, E. Askerov, V. Krever, S. Kalem, B. Avcioglu, S. Galstyan and R. Mnatsekanov 9 The Caucasus Hotspot N. -

Size Variations of Flowering Characters in Arum Italicum (Araceae)

M. GIBERNAU,]. ALBRE, 2008 101 Size Variations of Flowering Characters in Arum italicum (Araceae) Marc Gibernau· and Jerome Albre Universite Paul Sabatier Laboratoire d'Evolution & Diversite Biologique (UMR 5174) Bat.4R3-B2 31062 Toulouse cedex 9 France *e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION In Arum, bigger individuals should An extreme form of flowering character proportionally invest more in the female variations according to the size is gender function (number or weight of female modification, which occurs in several flowers) than the male. The aim of this species of Arisaema (Clay, 1993). Individ paper is to quantify variations in repro ual plant gender changes from pure male, ductive characters (size of the spadix when small, to monoecious (A. dracon parts, number of inflorescences) in rela tium) or pure female (A. ringens) when tion to plant and inflorescence sizes. The large (Gusman & Gusman, 2003). This appendix represents 44% of the spadix gender change is reversible, damaged length. The female zone length represents female individuals will flower as male the 16.5% of the spadix length and is much following year (Lovett Doust & Cavers, longer than the male zone (6%). Moreover 1982). These changes are related to change these three spadix zones increase with in plant size and are explained by the plant vigour indicating an increasing size-advantage model. The size-advantage investment into reproduction and pollina model postulates a sex change when an tor attraction. It appears that the length of increase in body size is related to differen appendix increased proportionally more tial abilities to produce or sire offspring than the lengths of the fertile zones. -

The General Status of Alberta Wild Species 2000 | I Preface

Pub No. I/023 ISBN No. 0-7785-1794-2 (Printed Edition) ISBN No. 0-7785-1821-3 (On-line Edition) For copies of this report, contact: Information Centre – Publications Alberta Environment/Alberta Sustainable Resource Development Main Floor, Great West Life Building 9920 - 108 Street Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T5K 2M4 Telephone: (780) 422-2079 OR Information Service Alberta Environment/Alberta Sustainable Resource Development #100, 3115 - 12 Street NE Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2E 7J2 Telephone: (403) 297-3362 OR Visit our website at www.gov.ab.ca/env/fw/status/index.html (available on-line Fall 2001) Front Cover Photo Credits: OSTRICH FERN - Carroll Perkins | NORTHERN LEOPARD FROG - Wayne Lynch | NORTHERN SAW-WHET OWL - Gordon Court | YELLOW LADY’S-SLIPPER - Wayne Lynch | BRONZE COPPER - Carroll Perkins | AMERICAN BISON - Gordon Court | WESTERN PAINTED TURTLE - Gordon Court | NORTHERN PIKE - Wayne Lynch ASPEN | gordon court prefacepreface Alberta has long enjoyed the legacy of abundant wild species. These same species are important environmental indicators. Their populations reflect the health and diversity of the environment. Alberta Sustainable Resource Development The preparation and distribution of this report is has designated as one of its core business designed to achieve four objectives: goals the promotion of fish and wildlife conservation. The status of wild species is 1. To provide information on, and raise one of the performance measures against awareness of, the current status of wild which the department determines the species in Alberta; effectiveness of its policies and service 2. To stimulate broad public input in more delivery. clearly defining the status of individual Central to achieving this goal is the accurate species; determination of the general status of wild 3. -

Appendix 2: Plant Lists

Appendix 2: Plant Lists Master List and Section Lists Mahlon Dickerson Reservation Botanical Survey and Stewardship Assessment Wild Ridge Plants, LLC 2015 2015 MASTER PLANT LIST MAHLON DICKERSON RESERVATION SCIENTIFIC NAME NATIVENESS S-RANK CC PLANT HABIT # OF SECTIONS Acalypha rhomboidea Native 1 Forb 9 Acer palmatum Invasive 0 Tree 1 Acer pensylvanicum Native 7 Tree 2 Acer platanoides Invasive 0 Tree 4 Acer rubrum Native 3 Tree 27 Acer saccharum Native 5 Tree 24 Achillea millefolium Native 0 Forb 18 Acorus calamus Alien 0 Forb 1 Actaea pachypoda Native 5 Forb 10 Adiantum pedatum Native 7 Fern 7 Ageratina altissima v. altissima Native 3 Forb 23 Agrimonia gryposepala Native 4 Forb 4 Agrostis canina Alien 0 Graminoid 2 Agrostis gigantea Alien 0 Graminoid 8 Agrostis hyemalis Native 2 Graminoid 3 Agrostis perennans Native 5 Graminoid 18 Agrostis stolonifera Invasive 0 Graminoid 3 Ailanthus altissima Invasive 0 Tree 8 Ajuga reptans Invasive 0 Forb 3 Alisma subcordatum Native 3 Forb 3 Alliaria petiolata Invasive 0 Forb 17 Allium tricoccum Native 8 Forb 3 Allium vineale Alien 0 Forb 2 Alnus incana ssp rugosa Native 6 Shrub 5 Alnus serrulata Native 4 Shrub 3 Ambrosia artemisiifolia Native 0 Forb 14 Amelanchier arborea Native 7 Tree 26 Amphicarpaea bracteata Native 4 Vine, herbaceous 18 2015 MASTER PLANT LIST MAHLON DICKERSON RESERVATION SCIENTIFIC NAME NATIVENESS S-RANK CC PLANT HABIT # OF SECTIONS Anagallis arvensis Alien 0 Forb 4 Anaphalis margaritacea Native 2 Forb 3 Andropogon gerardii Native 4 Graminoid 1 Andropogon virginicus Native 2 Graminoid 1 Anemone americana Native 9 Forb 6 Anemone quinquefolia Native 7 Forb 13 Anemone virginiana Native 4 Forb 5 Antennaria neglecta Native 2 Forb 2 Antennaria neodioica ssp. -

South American Cacti in Time and Space: Studies on the Diversification of the Tribe Cereeae, with Particular Focus on Subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae)

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2013 South American Cacti in time and space: studies on the diversification of the tribe Cereeae, with particular focus on subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae) Lendel, Anita Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-93287 Dissertation Published Version Originally published at: Lendel, Anita. South American Cacti in time and space: studies on the diversification of the tribe Cereeae, with particular focus on subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae). 2013, University of Zurich, Faculty of Science. South American Cacti in Time and Space: Studies on the Diversification of the Tribe Cereeae, with Particular Focus on Subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae) _________________________________________________________________________________ Dissertation zur Erlangung der naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorwürde (Dr.sc.nat.) vorgelegt der Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Zürich von Anita Lendel aus Kroatien Promotionskomitee: Prof. Dr. H. Peter Linder (Vorsitz) PD. Dr. Reto Nyffeler Prof. Dr. Elena Conti Zürich, 2013 Table of Contents Acknowledgments 1 Introduction 3 Chapter 1. Phylogenetics and taxonomy of the tribe Cereeae s.l., with particular focus 15 on the subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae – Cactoideae) Chapter 2. Floral evolution in the South American tribe Cereeae s.l. (Cactaceae: 53 Cactoideae): Pollination syndromes in a comparative phylogenetic context Chapter 3. Contemporaneous and recent radiations of the world’s major succulent 86 plant lineages Chapter 4. Tackling the molecular dating paradox: underestimated pitfalls and best 121 strategies when fossils are scarce Outlook and Future Research 207 Curriculum Vitae 209 Summary 211 Zusammenfassung 213 Acknowledgments I really believe that no one can go through the process of doing a PhD and come out without being changed at a very profound level. -

Lenka Kočková

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA PŘÍRODOVĚDECKÁ FAKULTA ÚSTAV BOTANIKY A ZOOLOGIE Velikost genomu a poměr bazí v genomu v čeledi Ranunculaceae Diplomová práce Lenka Kočková Vedoucí práce: Doc. RNDr. Petr Bureš, Ph. D. Brno 2012 Bibliografický záznam Autor: Bc. Lenka Kočková Přírodovědecká fakulta, Masarykova univerzita, Ústav botaniky a zoologie Název práce: Velikost genomu a poměr bazí v genomu v čeledi Ranunculaceae Studijní program: Biologie Studijní obor: Systematická biologie a ekologie (Botanika) Vedoucí práce: Doc. RNDr. Petr Bureš, Ph. D. Akademický rok: 2011/2012 Počet stran: 104 Klíčová slova: Ranunculaceae, průtoková cytometrie, PI/DAPI, DNA obsah, velikost genomu, GC obsah, zastoupení bazí, velikost průduchů, Pignattiho indikační hodnoty Bibliographic Entry Author: Bc. Lenka Kočková Faculty of Science, Masaryk University, Department of Botany and Zoology Title of Thesis: Genome size and genomic base composition in Ranunculaceae Programme: Biology Field of Study: Systematic Biology and Ecology (Botany) Supervisor: Doc. RNDr. Petr Bureš, Ph. D. Academic Year: 2011/2012 Number of Pages: 104 Keywords: Ranunculaceae, flow cytometry, PI/DAPI, DNA content, genome size, GC content, base composition, stomatal size, Pignatti‘s indicator values Abstrakt Pomocí průtokové cytometrie byla změřena velikost genomu a AT/GC genomový poměr u 135 druhů z čeledi Ranunculaceae. U druhů byla naměřena délka a šířka průduchů a z literatury byly získány údaje o počtu chromozomů a ekologii druhů. Velikost genomu se v rámci čeledi liší 63-krát. Nejmenší genom byl naměřen u Aquilegia canadensis (2C = 0,75 pg), největší u Ranunculus lingua (2C = 47,93 pg). Mezi dvěma hlavními podčeleděmi Ranunculoideae a Thalictroideae je ve velikosti genomu markantní rozdíl (2C = 2,48 – 47,94 pg a 0,75 – 4,04 pg).