Questions, Audiences and Securitization in the Proscription Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

All Party Parliamentary Group on British Muslims

All Party Parliamentary Group on British Muslims The inquiry into a working definition of Islamophobia Report on the inquiry into A working definition of Islamophobia / anti-Muslim hatred All Party Parliamentary Group on British Muslims Report on the inquiry into a working definition of Islamophobia / anti-Muslim hatred 3 The All Party Parliamentary Group on British Muslims was launched in 2017. The cross party group of parliamentarians is co-chaired by Anna Soubry MP and Wes Streeting MP. The Group was established to highlight the aspirations and challenges facing British Muslims; to celebrate the contributions of Muslim communities to Britain and to investigate prejudice, discrimination and hatred against Muslims in the UK. appgbritishmuslims.org facebook.com/APPGBritMuslims @APPGBritMuslims Report on the inquiry into A working definition of Islamophobia / anti-Muslim hatred All Party Parliamentary Group on British Muslims Contents Foreword by Dominic Grieve QC 6 Foreword by Anna Soubry and Wes Streeting 7 Executive Summary 9 Introduction 12 Chapter 1 Literature review 19 Chapter 2 - Arriving at a working definition 23 Chapter 3 - Our findings 27 An INDEX to Tackle Islamophobia 51 Chapter 4 - Community consultation findings 52 Conclusion 56 Acknowledgements 60 Appendix 1 - Written evidence 61 Appendix 2 - Oral evidence sessions 62 Appendix 3 - Community consultation participants 63 Appendix 4 - Islamophobia / Anti Muslim hatred questionnaire 64 Bibliography 66 5 Foreword s Chair of the Citizens UK Commission on Islam, Participation and Public Life, I travelled round the country hearing evidence as to the extent to which this desirable goal was taking place and as to the reasons why it was not happening Ain the way many Muslims and others wished. -

Organised With: Fabian Summer Conference 2016 Britain's Future, Labour's Future Saturday 21 May 2016, 09.30 – 17.15 TUC Co

Organised with: Fabian Summer conference 2016 Britain’s Future, Labour’s Future Saturday 21 May 2016, 09.30 – 17.15 TUC Congress Centre, 28 Great Russell Street, London, WC1B 3LS 9.30-10.20 Registration Tea and coffee 10.20-10.45 Welcome Main Hall Andrew Harrop (general secretary, Fabian Society) Massimo D’Alema (president, Foundation for European Progressive Studies) 10.45-11.30 Keynote speech Main Hall Gordon Brown (former prime minister) 11.30-12.20 Morning Plenary ‘Should we stay or should we go now’: What should the left decide? Main Hall Caroline Flint MP (Labour MP, Don Valley) Baroness Jenny Jones (Green Party, Member of the House of Lords) Tim Montgomerie (columnist, The Times) Chair: Andrew Harrop, (general secretary, Fabian Society) 12.30-13.30 Breakout sessions Main Hall It’s the economy, stupid: what’s best for jobs and growth? Shabana Mahmood MP (Labour MP, Birmingham Ladywood) John Mills (deputy chair, Vote Leave) Lucy Anderson MEP (Labour MEP for London) Vicky Pryce (economist) Chair: Michael Izza (chief executive, ICAEW) Council Chamber The jury’s out: can the campaigns persuade the ‘undecideds’? Interactive session Brendan Chilton (general secretary, Labour Leave) Antonia Bance (head of campaigns and communications, TUC) Richard Angell (director, Progress) Chair: Felicity Slater (exec member, Fabian Women’s Network) Meeting Room 1 Drifting apart? The four nations and Europe Nia Griffith MP (shadow secretary of state for wales and Labour MP for Llanelli) John Denham (director, University of Winchester’s Centre for English -

One Nation: Power, Hope, Community

one nation power hope community power hope community Ed Miliband has set out his vision of One Nation: a country where everyone has a stake, prosperity is fairly shared, and we make a common life together. A group of Labour MPs, elected in 2010 and after, describe what this politics of national renewal means to them. It begins in the everyday life of work, family and local place. It is about the importance of having a sense of belonging and community, and sharing power and responsibility with people. It means reforming the state and the market in order to rebuild the economy, share power hope community prosperity, and end the living standards crisis. And it means doing politics in a different way: bottom up not top down, organising not managing. A new generation is changing Labour to change the country. Edited by Owen Smith and Rachael Reeves Contributors: Shabana Mahmood Rushanara Ali Catherine McKinnell Kate Green Gloria De Piero Lilian Greenwood Steve Reed Tristram Hunt Rachel Reeves Dan Jarvis Owen Smith Edited by Owen Smith and Rachel Reeves 9 781909 831001 1 ONE NATION power hope community Edited by Owen Smith & Rachel Reeves London 2013 3 First published 2013 Collection © the editors 2013 Individual articles © the author The authors have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Design and Patents Act, 1998 to be identified as authors of this work. All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, electrical, chemical, mechanical, optical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. -

View Questions Tabled on PDF File 0.16 MB

Published: Monday 5 July 2021 Questions tabled on Friday 2 July 2021 Includes questions tabled on earlier days which have been transferred. T Indicates a topical oral question. Members are selected by ballot to ask a Topical Question. † Indicates a Question not included in the random selection process but accepted because the quota for that day had not been filled. N Indicates a question for written answer on a named day under S.O. No. 22(4). [R] Indicates that a relevant interest has been declared. Questions for Answer on Monday 5 July Questions for Written Answer 1 N Angela Rayner (Ashton-under-Lyne): To ask the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and Minister for the Cabinet Office, what assessment he has made of the accuracy of the Prime Minister's Official Spokesperson's statement of 28 June 2021 on the conduct of ministerial government business through departmental email addresses. [Transferred] (24991) 2 Dr Matthew Offord (Hendon): To ask the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, what assessment his Department has made of the potential merits of setting a target for onshore wind ahead of COP26. [Transferred] (25780) 3 Stephen Morgan (Portsmouth South): To ask the Secretary of State for Education, what steps he is taking to ensure that all children receive LGBTQ+ inclusive education. [Transferred] (25919) 4 Jim Shannon (Strangford): To ask the Secretary of State for International Trade, what recent progress has been made towards agreeing a trade deal with Australia. [Transferred] (25817) 5 Daisy Cooper (St Albans): To ask the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, if he will offer reimbursements to the single cohort of speech and language therapy undergraduates who self-funded their degrees when starting university in September 2017 before Government funding was re-instated. -

Shadow Cabinet Meetings with Proprietors, Editors and Senior Media Executives

Shadow Cabinet Meetings 1 June 2015 – 31 May 2016 Shadow cabinet meetings with proprietors, editors and senior media executives. Andy Burnham MP Shadow Secretary of State’s meetings with proprietors, editors and senior media executives Date Name Location Purpose Nature of relationship* 26/06/2015 Alison Phillips, Editor, Roast, The General Professional Sunday People Floral Hall, discussion London, SE1 Peter Willis, Editor, 1TL Daily Mirror 15/07/2015 Lloyd Embley, Editor in J Sheekey General Professional Chief, Trinity Mirror Restaurant, discussion 28-32 Saint Peter Willis, Editor, Martin's Daily Mirror Court, London WC2N 4AL 16/07/2015 Kath Viner, Editor in King’s Place Guardian daily Professional Chief, Guardian conference 90 York Way meeting London N1 2AP 22/07/2015 Evgeny Lebedev, Private General Professional proprieter, address discussion Independent/Evening Standard 04/08/2015 Lloyd Embley, Editor in Grosvenor General Professional Chief, Trinity Mirror Hotel, 101 discussion Buckingham Palace Road, London SW1W 0SJ 16/05/2016 Eamonn O’Neal, Manchester General Professional Managing Editor, Evening Manchester Evening News, discussion News Mitchell Henry House, Hollinwood Avenue, Chadderton, Oldham OL9 8EF Other interaction between Shadow Secretary of State and proprietors, editors and senior media executives Date Name Location Purpose Nature of relationship* No such meetings Angela Eagle MP Shadow Secretary of State’s meetings with proprietors, editors and senior media executives Date Name Location Purpose Nature of relationship* No -

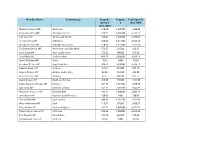

Stephen Kinnock MP Aberav

Member Name Constituency Bespoke Postage Total Spend £ Spend £ £ (Incl. VAT) (Incl. VAT) Stephen Kinnock MP Aberavon 318.43 1,220.00 1,538.43 Kirsty Blackman MP Aberdeen North 328.11 6,405.00 6,733.11 Neil Gray MP Airdrie and Shotts 436.97 1,670.00 2,106.97 Leo Docherty MP Aldershot 348.25 3,214.50 3,562.75 Wendy Morton MP Aldridge-Brownhills 220.33 1,535.00 1,755.33 Sir Graham Brady MP Altrincham and Sale West 173.37 225.00 398.37 Mark Tami MP Alyn and Deeside 176.28 700.00 876.28 Nigel Mills MP Amber Valley 489.19 3,050.00 3,539.19 Hywel Williams MP Arfon 18.84 0.00 18.84 Brendan O'Hara MP Argyll and Bute 834.12 5,930.00 6,764.12 Damian Green MP Ashford 32.18 525.00 557.18 Angela Rayner MP Ashton-under-Lyne 82.38 152.50 234.88 Victoria Prentis MP Banbury 67.17 805.00 872.17 David Duguid MP Banff and Buchan 279.65 915.00 1,194.65 Dame Margaret Hodge MP Barking 251.79 1,677.50 1,929.29 Dan Jarvis MP Barnsley Central 542.31 7,102.50 7,644.81 Stephanie Peacock MP Barnsley East 132.14 1,900.00 2,032.14 John Baron MP Basildon and Billericay 130.03 0.00 130.03 Maria Miller MP Basingstoke 209.83 1,187.50 1,397.33 Wera Hobhouse MP Bath 113.57 976.00 1,089.57 Tracy Brabin MP Batley and Spen 262.72 3,050.00 3,312.72 Marsha De Cordova MP Battersea 763.95 7,850.00 8,613.95 Bob Stewart MP Beckenham 157.19 562.50 719.69 Mohammad Yasin MP Bedford 43.34 0.00 43.34 Gavin Robinson MP Belfast East 0.00 0.00 0.00 Paul Maskey MP Belfast West 0.00 0.00 0.00 Neil Coyle MP Bermondsey and Old Southwark 1,114.18 7,622.50 8,736.68 John Lamont MP Berwickshire Roxburgh -

Identity Crisis

Feature FABIAN REVIEW The quarterly magazine of the Fabian Society Autumn 2019 / fabians.org.uk / £4.95 IDENTITY CRISIS Paul Mason and Pete Dorey on the battle for the souls of the Labour and Conservative parties and Zubaida Haque on being British p10 / Richard Carr traces the march of the moderates p16 / Stella Creasy talks campaigning, change and choices p24 1 / Fabian Review Does Labour have a progressive plan for the NHS? Sunday 22 September Holiday Inn 12.30 –2pm Brighton Seafront PROPOSED PANEL: • Becky Wright, Unions 21 (Chair) • Jon Skewes, RCM • Rob Yeldham, CSP alongside health professionals and policy makers ROYAL COLLEGE OF MIDWIVES WITH CHARTERED SOCIETY OF PHYSIOTHERAPY Campaigning for the proper care older people deserve. www.ageuk.org.uk/campaigns Age UK, Tavis House, 1-6 Tavistock Square, London WC1H 9NA. Registered charity number 1128267. Age UK half page_310719.indd 1 31/07/2019 16:02 Contents FABIAN REVIEW Volume 131 —No.3 Leader Andrew Harrop 4 Facing the voters Shortcuts Tulip Siddiq MP 5 Mind the gaps Danny Beales 6 A council house renaissance Ali Milani 7 Taking on the PM Hannah O’Rourke and Shabana Mahmood MP 7 The art of bridge-building Dean Mukeza 8 A space to heal Rosena Allin-Khan MP 9 Dangerous delays Cover story Paul Mason 10 Labour’s big challenge Pete Dorey 12 Totalitarian Toryism Zubaida Haque 14 Real belonging Essay Richard Carr 16 Sweet moderation Comment Marjorie Kelly 19 The next big idea Rosie Duffield MP 21 The age of alliances Interview Kate Murray 24 Change makers Features Lord Kennedy 28 Unfinished business Daniel Johnson MSP 30 Mayoral matters Theo Bass 31 Data for the many Satbir Singh 32 Litmus test for the left Nandita Sharma 35 Goodbye to borders Books Mhairi Tordoff 36 Home truths Janette Martin 37 Filling the gaps Fabian Society section Wayne David MP 38 A true pioneer 39 Annual report 41 Noticeboard & quiz FABIAN REVIEW FABIAN SOCIETY Events and stakeholder assistant, Research Fabian Review is the quarterly journal of the Fabian 61 Petty France Natasha Wakelin Deputy general secretary, Society. -

NEC Annual Report 2019

Labour Party | Annual Report 2019 LABOUR PARTY ANNUAL REPORT 2019 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Treasurers’ Responsibilities . 54 Foreword from Jeremy Corbyn . 5 Independent Auditor’s Report Introduction from Tom Watson . 7 to the members of the Labour Party . 55 Introduction from the General Secretary . 9 Consolidated income and expenditure account 2018/2019 National Executive Committee . 10 for the year ended 31 December 2018 . 57 NEC Committees . 12 Statements of comprehensive income Obituaries . 13 and changes in equity for the year ended NEC aims and objectives for 2019 . 14 31 December 2018 . 58 Consolidated balance sheet BY-ELECTIONS . 15 at 31 December 2018 . 59 Peterborough . 16 Consolidated cash flow statement for the year Newport West . 17 ended 31 December 2018 . 60 ELECTIONS 2019 . 19 Notes to Financial Statements . 61 Analysis . 20 APPENDICES . 75 Local Government Report . 23 Members of Shadow Cabinet LOOKING AHEAD: 2020 ELECTIONS . 25 and Opposition Frontbench . 76 The year ahead in Scotland . 26 Parliamentary Labour Party . 80 The year ahead in Wales . 27 Members of the Scottish Parliament. 87 NEC PRIORITIES FOR 2019 . 29 Members of the Welsh Assembly . 88 Members and Supporters Members of the European Parliament . 89 Renewing our party and building an active Directly Elected Mayors . 90 membership and supporters network . 30 Members of the London Assembly . 91 Equalities . 31 Leaders of Labour Groups . 92 Labour Peers . 100 NEC PRIORITIES FOR 2019 . 35 Labour Police and Crime Commissioners . 103 National Policy Forum Parliamentary Candidates endorsed NPF Report . 36 by the NEC at time of publication . 104 NEC PRIORITIES FOR 2019 . 39 NEC Disputes . 107 International NCC Cases . -

A Record Number of British Pakistanis in Parliament the 56Th UK General Election Saw a Record Number of British Pakistanis Being Elected to Parliament

*|MC:SUBJECT|* Page 1 of 7 Tweet Forward +1 Share Share Dear Readers, This May, the British Pakistani community has much to celebrate. The UK's 56th General Election saw a record number of ethnic Pakistanis being elected as MPs. With ten seats in Parliament, the community has never been so well represented in the political sphere in the UK. This historic result represents the mainstreaming of the community. We are proud of the achievements and efforts of our fellow British Pakistanis and wish to celebrate their success. And so, we have dedicated this edition of the newsletter to applauding the re-elected and newly elected British Pakistani MPs. We are also delighted to announce two upcoming BPF events. BPF's Women's Network has collaborated with playwright and actor, Aizzah Fatima, to host a story-telling workshop and tickets for her solo comedy show, Dirty Paki Lingerie. In June, BPF will also be convening its second Business and Professionals Club event. The function is a follow-up after the resounding success of our Business and Professionals Network launch event in March and will focus on entrepreneurship and business pitching. While there have been many positive developments here in the UK, we are outraged and deeply saddened by events in Pakistan; the attack on the Ismaili community, and the murder of civil society activist Sabeen Mahmud. Our heart goes out the victims of the senseless violence in Pakistan, and we hope and pray for a peaceful and tolerant country. Best Wishes, The British Pakistan Foundation Team A Record Number of British Pakistanis in Parliament The 56th UK General Election saw a record number of British Pakistanis being elected to Parliament. -

Fitting the Bill: Bringing Commons Legislation Committees Into Line with Best Practice

DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE FITTING THE BILL BRINGING COMMONS LEGISLATION COMMITTEES INTO LINE WITH BEST PRACTICE MEG RUSSELL, BOB MORRIS AND PHIL LARKIN Fitting the Bill: Bringing Commons legislation committees into line with best practice Meg Russell, Bob Morris and Phil Larkin Constitution Unit June 2013 ISBN: 978-1-903903-64-3 Published by The Constitution Unit School of Public Policy UCL (University College London) 29/30 Tavistock Square London WC1H 9QU Tel: 020 7679 4977 Fax: 020 7679 4978 Email: [email protected] Web: www.ucl.ac.uk/constitution-unit/ ©The Constitution Unit, UCL 2013 This report is sold subject to the condition that is shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. First Published June 2013 2 Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................... 4 Executive summary ............................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 7 Part I: The current system .................................................................................................... 9 The Westminster legislative process in -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Monday Volume 687 18 January 2021 No. 161 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 18 January 2021 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2021 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 601 18 JANUARY 2021 602 David Linden [V]: Under the Horizon 2020 programme, House of Commons the UK consistently received more money out than it put in. Under the terms of this agreement, the UK is set to receive no more than it contributes. While universities Monday 18 January 2021 in Scotland were relieved to see a commitment to Horizon Europe in the joint agreement, what additional funding The House met at half-past Two o’clock will the Secretary of State make available to ensure that our overall level of research funding is maintained? PRAYERS Gavin Williamson: As the hon. Gentleman will be aware, the Government have been very clear in our [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] commitment to research. The Prime Minister has stated Virtual participation in proceedings commenced time and time again that our investment in research is (Orders, 4 June and 30 December 2020). absolutely there, ensuring that we deliver Britain as a [NB: [V] denotes a Member participating virtually.] global scientific superpower. That is why more money has been going into research, and universities will continue to play an incredibly important role in that, but as he Oral Answers to Questions will be aware, the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy manages the research element that goes into the funding of universities. -

Daily Report Tuesday, 20 April 2021 CONTENTS

Daily Report Tuesday, 20 April 2021 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 20 April 2021 and the information is correct at the time of publication (06:26 P.M., 20 April 2021). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 11 UK Trade with EU 19 ATTORNEY GENERAL 11 UK Trade with EU: Exports 20 Attorney General: West Veterans: Charities 20 Yorkshire 11 Voting Behaviour: Travellers 21 Trials 11 DEFENCE 21 BUSINESS, ENERGY AND A400M Aircraft 21 INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 12 Afghanistan: Immigration 21 Africa: Research 12 Africa: Islamic State 22 Consumer Goods: Counterfeit Manufacturing 13 Armed Forces Covenant: Scottish Borders 22 CABINET OFFICE 13 Armed Forces: Autism 23 10 Downing Street: Construction 13 Armoured Fighting Vehicles: Iron and Steel 23 10 Downing Street: Facilities 13 Army: Recruitment 23 Blood: Contamination 14 Bahrain: Defence 24 Cabinet Office: Equality 14 Cyprus: Military Bases 24 Census: Forms 15 Oman: Defence 24 Coronavirus: Vaccination 15 Qatar: Defence 24 Government Departments: Epilepsy 16 Service Pupil Premium 25 Greensill 16 Type 31 Frigates: Iron and Steel 25 Honours: Forfeiture 17 USA: Arms Trade 26 Internet: Elderly 18 DIGITAL, CULTURE, MEDIA AND Members: Correspondence 18 SPORT 26 Students: Absent Voting 18 David Cameron 26 Trade Promotion 19 Department for Digital, Higher Education: Remote Culture, Media and Sport: Education 43 West Yorkshire 26 Languages: GCE