Airpower, from the Ground Up

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bendheim Senior Thesis Department of History, Columbia University

INCENDIARY WARS: The Transformation of United States Air Force Bombing Policy in the WWII Pacific Theater Gilad Bendheim Senior Thesis Department of History, Columbia University Faculty Advisor: Professor Mark Mazower Second Reader: Professor Alan Brinkley INCENDIARY WARS 1 Note to the Reader: For the purposes of this essay, I have tried to adhere to a few conventions to make the reading easier. When referring specifically to a country’s aerial military organization, I capitalize the name Air Force. Otherwise, when simply discussing the concept in the abstract, I write it as the lower case air force. In accordance with military standards, I also capitalize the entire name of all code names for operations (OPERATION MATTERHORN or MATTERHORN). Air Force’s names are written out (Twentieth Air Force), the bomber commands are written in Roman numerals (XX Bomber Command, or simply XX), while combat groups are given Arabic numerals (305th Bomber Group). As the story shifts to the Mariana Islands, Twentieth Air Force and XXI Bomber Command are used interchangeably. Throughout, the acronyms USAAF and AAF are used to refer to the United States Army Air Force, while the abbreviation of Air Force as “AF” is used only in relation to a numbered Air Force (e.g. Eighth AF). Table of Contents: Introduction 3 Part I: The (Practical) Prophets 15 Part II: Early Operations Against Japan 43 Part III: The Road to MEETINGHOUSE 70 Appendix 107 Bibliography 108 INCENDIARY WARS 2 Introduction Curtis LeMay sat awake with his trademark cigar hanging loosely from his pursed ever-scowling lips (a symptom of his Bell’s Palsy, not his demeanor), with two things on his mind. -

Order of Battle, Mid-September 1940 Army Group a Commander-In-Chief

Operation “Seelöwe” (Sea Lion) Order of Battle, mid-September 1940 Army Group A Commander-in-Chief: Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt Chief of the General Staff: General der Infanterie Georg von Sodenstern Operations Officer (Ia): Oberst Günther Blumentritt 16th Army Commander-in-Chief: Generaloberst Ernst Busch Chief of the General Staff: Generalleutnant Walter Model Operations Officer (Ia): Oberst Hans Boeckh-Behrens Luftwaffe Commander (Koluft) 16th Army: Oberst Dr. med. dent. Walter Gnamm Division Command z.b.V. 454: Charakter als Generalleutnant Rudolf Krantz (This staff served as the 16th Army’s Heimatstab or Home Staff Unit, which managed the assembly and loading of all troops, equipment and supplies; provided command and logistical support for all forces still on the Continent; and the reception and further transport of wounded and prisoners of war as well as damaged equipment. General der Infanterie Albrecht Schubert’s XXIII Army Corps served as the 16th Army’s Befehlsstelle Festland or Mainland Command, which reported to the staff of Generalleutnant Krantz. The corps maintained traffic control units and loading staffs at Calais, Dunkirk, Ostend, Antwerp and Rotterdam.) FIRST WAVE XIII Army Corps: General der Panzertruppe Heinric h-Gottfried von Vietinghoff genannt Scheel (First-wave landings on English coast between Folkestone and New Romney) – Luftwaffe II./Flak-Regiment 14 attached to corps • 17th Infantry Division: Generalleutnant Herbert Loch • 35th Infantry Division: Generalleutnant Hans Wolfgang Reinhard VII Army -

Explosive Weapon Effectsweapon Overview Effects

CHARACTERISATION OF EXPLOSIVE WEAPONS EXPLOSIVEEXPLOSIVE WEAPON EFFECTSWEAPON OVERVIEW EFFECTS FINAL REPORT ABOUT THE GICHD AND THE PROJECT The Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) is an expert organisation working to reduce the impact of mines, cluster munitions and other explosive hazards, in close partnership with states, the UN and other human security actors. Based at the Maison de la paix in Geneva, the GICHD employs around 55 staff from over 15 countries with unique expertise and knowledge. Our work is made possible by core contributions, project funding and in-kind support from more than 20 governments and organisations. Motivated by its strategic goal to improve human security and equipped with subject expertise in explosive hazards, the GICHD launched a research project to characterise explosive weapons. The GICHD perceives the debate on explosive weapons in populated areas (EWIPA) as an important humanitarian issue. The aim of this research into explosive weapons characteristics and their immediate, destructive effects on humans and structures, is to help inform the ongoing discussions on EWIPA, intended to reduce harm to civilians. The intention of the research is not to discuss the moral, political or legal implications of using explosive weapon systems in populated areas, but to examine their characteristics, effects and use from a technical perspective. The research project started in January 2015 and was guided and advised by a group of 18 international experts dealing with weapons-related research and practitioners who address the implications of explosive weapons in the humanitarian, policy, advocacy and legal fields. This report and its annexes integrate the research efforts of the characterisation of explosive weapons (CEW) project in 2015-2016 and make reference to key information sources in this domain. -

Airpower in the Battle of the Bulge: a Case for Effects-‐‑Based Operations?

Journal of Military and Strategic VOLUME 14, ISSUE 1, FALL 2011 Studies Airpower in the Battle of the Bulge: A Case for Effects-Based Operations? Harold R. Winton ȱ ȱ dzȱ ¢ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ throughout are those of a campaign on land in which the primary problem at the time is the defeat of an enemy army in the field.1 J.C. Slessor, 1936 ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ Ȃȱ work, Air Power and Armies, the published version of lectures he presented to his army brethren at the Staff College, Camberley in the mid-ŗşřŖǯȱ ȱ Ȃȱ ǰȱ ȱ paper is focused historically on an air effort to defeat an enemy army, or in this case an army groupȯField Marshal ȱȂȱ¢ȱ ȱǰȱȱȱȱ to which Adolf Hitler entrusted his last, desperate gamble to win World War IIȯa campaign that became known in history as the Battle of the Bulge. But in keeping with ȱ ȱ ȱ ȃ ȱ ǰȄȱ t will relate the course and consequences of that campaign to an ongoing doctrinal debate in the American armed forces over a concept known as Effects-Based Operations, or EBO. The issue on the table is to determine the 1 J.C. Slessor, Air Power and Armies (London: Oxford University Press, 1936), p. xi. ©Centre of Military and Strategic Studies, 2011 ISSN : 1488-559X JOURNAL OF MILITARY AND STRATEGIC STUDIES extent to which the evidence of using airpower in the Bulge confirms, qualifies, or refutes the tenets of EBO. While this question may seem somewhat arcane, it is not without consequence. -

Fighting Patton Photographs

Fighting Patton Photographs [A]Mexican Punitive Expedition pershing-villa-obregon.tif: Patton’s first mortal enemy was the commander of Francisco “Pancho” Villa’s bodyguard during the Mexican Punitive Expedition. Left to right: General Álvaro Obregón, Villa, Brig. Gen. John Pershing, Capt. George Patton. [A]World War I Patton_France_1918.tif: Col. George Patton with one of his 1st Tank Brigade FT17s in France in 1918. Diepenbroick-Grüter_Otto Eitel_Friedrich.tif: Prince Freiherr von.tif: Otto Freiherr Friedrich Eitel commanded the von Diepenbroick-Grüter, 1st Guards Division in the pictured as a cadet in 1872, Argonnes. commanded the 10th Infantry Division at St. Mihiel. Gallwitz_Max von.tif: General Wilhelm_Crown Prince.tif: Crown der Artillerie Max von Prince Wilhelm commanded the Gallwitz’s army group defended region opposite the Americans. the St. Mihiel salient. [A]Morocco and Vichy France Patton_Hewitt.tif: Patton and Rear Admiral Henry Kent Hewitt, commanding Western Naval Task Force, aboard the Augusta before invading Vichy-controlled Morocco in Operation Torch. NoguesLascroux: Arriving at Fedala to negotiate an armistice at 1400 on 11 November 1942, Gen. Charles Noguès (left) is met by Col. Hobart Gay. Major General Auguste Lahoulle, Commander of French Air Forces in Morocco, is on the right. Major General Georges Lascroux, Commander in Chief of Moroccan troops, carries a briefcase. Noguès_Charles.tif: Charles Petit_Jean.tif: Jean Petit, Noguès, was Vichy commander- commanded the garrison at in-chief in Morocco. Port Lyautey. (Courtesy of Stéphane Petit) [A]The Axis Powers Patton_Monty.tif: Patton and his rival Gen. Bernard Montgomery greet each other on Sicily in July 1943. The two fought the Axis powers in Tunisia, Sicily, and the European theater. -

Former Warsaw Pact Ammunition Handbook, Vol 3

NATO Explosive Ordnance Disposal Centre of Excellence FORMER WARSAW PACT AMMUNITION HANDBOOK VOLUME 3 Air Forces Ammunition Aerial projectiles, bombs, rockets and missiles TRENČÍN 2019 Slovak Republic For Official Use Only Explosive Ordnance Disposal Centre of Excellence FORMER WARSAW PACT AMMUNITION HANDBOOK VOLUME 3 Air Forces Ammunition Aerial projectiles, bombs, rockets and missiles For Official Use Only Explosive Ordnance Disposal Centre of Excellence The NATO Explosive Ordnance Centre of Excellence (NATO EOD COE) supports the efforts of the Alliance in the areas of training and education, information sharing, doctrine development and concepts validation. Published by NATO EOD Centre of Excellence Ivana Olbrachta 5, 911 01,Trenčín, Slovak Republic Tel. + 421 960 333 502, Fax + 421 960 333 504 www.eodcoe.org Former Warsaw Pact Ammunition Handbook VOL 3 – Edition II. ISBN 978-80-89261-81-9 © EOD Centre of Excellence. All rights reserved 2019 No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without the written permission of the publisher, except in the case brief quotations embodied in articles and reviews. For Official Use Only Explosive Ordnance Disposal Centre of Excellence Foreword Even though in areas of current NATO operations the insurgency is vastly using the Home Made Explosive as the main charge for emplaced IEDs, our EOD troops have to cope with the use of the conventional munition in any form and size all around the world. To assist in saving EOD Operators’ lives and to improve their effectiveness at munition disposal, it is essential to possess the adequate level of experience and knowledge about the respective type of munition. -

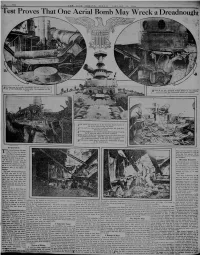

Test Proves That One Aerial Bomb Maywreck a Dreadnought

" " " * v " **. ^»*i>l-' J U ill/ A 1 LIB, , il.iiM Altl ¿ ¿ , 1 íJ ¿ 1 I I_.' ___ _ Test Proves That One Aerial Bomb May Wreck a Dreadnought A LL that was left of the wheelhouse and the forward fun- **¦ nel of the battleship Indiana after the explosion of the bomb '"TI/RECK of the forward 8-inch turret of the Indiana, j against tvhich the 900-pound bomb ivas exploded F "" smmsMsmsssssssssssimsmssMsssssssMswsMSSMsWSMsss^ rVHE bomb was the ¦*¦ placed aft of forward 8-inch turret at the point indicated by the arrmo i ; A T the left is a view of the vessel the amidships> first deck { .,.** being blown away \ A T THE right is a view of the second deck looking forward, ^ the X showing where the bomb exploded j ITHE picture at the lower left hand show's the third deck and -* the ammunition hoist. Had the ship been in commission the magazine probably ivould have been exploded j AT the lower hand is shown the **¦ right destruction wrought I on the fourth deck I _..-..__ ____-.... < By Quarterdeck THE seven pictures on this page there, and the campaign could not suffice to show the destruc¬ have been undertaken at all if th« tive effect of a bomb, not only Turks had been supplied with ar- on the upper works of a air force, not to speak of submarine* battleship, and bot upon the lower decks as well. torpedoes. In this case the target was the Discussion Demanded old battleship Indiana, formerly This article is not sensational It commanded by Captain H. -

A War of Reputation and Pride

A War of reputation and pride - An examination of the memoirs of German generals after the Second World War. HIS 4090 Peter Jørgen Sager Fosse Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History University of Oslo Spring 2019 1 “For the great enemy of truth is very often not the lie -- deliberate, contrived and dishonest -- but the myth -- persistent, persuasive, and unrealistic.” – John F. Kennedy, 19621 1John F. Kennedy, Yale University Commencement Address, https://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/jfkyalecommencement.htm, [01.05.2019]. 2 Acknowledgments This master would not have been written without the help and support of my mother, father, friends and my better half, thank you all for your support. I would like to thank the University Library of Oslo and the British Library in London for providing me with abundant books and articles. I also want to give huge thanks to the Military Archive in Freiburg and their employees, who helped me find the relevant materials for this master. Finally, I would like to thank my supervisor at the University of Oslo, Professor Kim Christian Priemel, who has guided me through the entire writing process from Autumn 2017. Peter Jørgen Sager Fosse, Oslo, 01.05.2019 3 Contents: Introduction………………………………………………………………………...………... 7 Chapter 1, Theory and background………………………………………………..………17 1.1 German Military Tactics…………………………………………………..………. 17 1.1.1 Blitzkrieg, Kesselschlacht and Schwerpunkt…………………………………..……. 17 1.1.2 Examples from early campaigns……………………………………………..……… 20 1.2 The German attack on the USSR (1941)……………………………..…………… 24 1.2.1 ‘Vernichtungskrieg’, war of annihilation………………………………...………….. 24 1.2.2 Operation Barbarossa………………………………………………..……………… 28 1.2.3 Operation Typhoon…………………………………………………..………………. 35 1.2.4 The strategic situation, December 1941…………………………….………………. -

Hitlerjugend Division Looms Over the Graves of Its Crew

Cover Rapid Reads This short ebook is part of the “Rapid Reads” series on the German Army of World War II. This series, when complete, will offer a comprehensive overview of this absorbing topic, covering the key campaigns, tactics, commanders and equipment of the World War II Wehrmacht. We hope you enjoy this Rapid Read and that you will recommend the series to friends and colleagues. You should be able to read one of these handy eBooks in less than an hour. They’re designed for busy people on the go. If you would like to place a review on our website, or with the retailer you purchased it from, please do so. All feedback, positive or negative, is appreciated. All these Rapid Reads plus supplemental materials and ebooks on other military topics are available on our website, www.germanwarmachine.com 0 10 20km Bareur 0 5 10 miles Cherbourg St-Vaast-la-Hogue Siouville-Hague Valognes Le Havre St Mere Eglise Grandcamp Douve Courseulles Portbail Issigny Esque Carentan Bayeux Ouistreham Cabourg Touques Créances St Fromond Cerisy-le-Forêt Vie Caen Lisieux St Lô Odon Vire Drôme Villers Bocage Coutancés Orne St-Pierre- Guilberville Thury Harcourt sur-Dives Villedieu-des-Poêles Vire Falaise Granville A knocked out Panzer IV of the I SS Panzer Corps’ Hitlerjugend Division looms over the graves of its crew. The Hitlerjugend Division held the line north of Caen, but at a terrible price in both men and equipment Carnage at Caen The 12th SS Panzer Division and the defence of Caen. 5 n its billets northwest of Paris, the men of the Hitlerjugend IDivision could clearly hear the waves of Allied bombers passing overhead on the morning of 6 June 1944. -

Heeresgruppe B (Army Group B)

RECORDS OF GERMAN FIELD COMMANDS, ARMY GROUPS (PART II) Heeresgruppe B (Army Group B) Army Group B was formed from the prior Army Group North on October 5, 1939, and was placed in the West until September 1940 when it was moved, after a short stay in Germany, to the German-Soviet border area in occupied Poland. On April 1, 194-1, it was renamed Army Group Center. Army Group South was designated Army Group B in July 194-2 and controlled the armies advancing in the region between Stalingrad and Kursk. Disbanded in February 194-3 it was re-formed in May 194-3 as OKW-Auffrischungs- stab Rommel. In July 194-3 it was reorganized as Army Group B and was located in south Germany, the Balkans, north Italy, and France. The Army Group was charged with control of anti-invasion forces along the Channel coast and was commanded by Gen, Erwin Rommel until July 1944-• Field Marshal Guenter von Kluge took it over for a short time and from August 18, 1944, until the capitulation it was under Field Marshal Walter Model. Army Group B took part in operations in France and controlled the Ardennes counteroffensive,* Item Item No. Roll 1st Frame Ic, Anlage zum T'atigkeitsbericht. Reports relating to the political and military situation in Italy, Italy's capitulation, and disarmament of Italian units; also includes German military communiques. Jul 30 - Nov 14-, 194-3• 49354 276 Ic, Meldungen. Daily activity reports covering Allied progress in France. Jul 1 - Dec 31, 1944. 65881/1-2 276 195 Ic, Meldungen. -

Concept Plan for the Destruction of Eight Old Chemical Weapons

OPCW Executive Council Eighty-Fifth Session EC-85/NAT.2 11 – 14 July 2017 16 June 2017 ENGLISH Original: SPANISH PANAMA CONCEPT PLAN FOR THE DESTRUCTION OF EIGHT OLD CHEMICAL WEAPONS Background 1. The Republic of Panama has declared eight (8) old chemical weapons to be destroyed. The weapons are located on San José Island, off the Southern coast of Panama’s mainland. The eight chemical munitions are World War II-era and comprised of: six (6) M79, 1,000 lb. aerial bombs believed to contain the Schedule 3 toxic chemical phosgene (CG), also known as carbonyl dichloride; one (1) M78, 500 lb. aerial bomb believed to contain the Schedule 3 toxic chemical cyanogen chloride (CK); and one (1) M1A1 Cylinder, which has been confirmed empty and rusted through and which the Republic of Panama and the Technical Secretariat (hereinafter “the Secretariat”) of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) considered destroyed. All eight of these munitions were identified in the 2002 OPCW Technical Secretariat Final Inspection Report. 2. The Republic of Panama has determined that the seven bombs are unsafe to move because of their explosive configuration, age, and austere location. These characteristics were noted in the 2002 OPCW Technical Secretariat Final Inspection Report. Relocation would pose an undue risk to workers attempting to move them and to the environment. As such, the Republic of Panama plans to destroy the munitions in place. 3. The OPCW Secretariat agrees with the Republic of Panama’s assessment that there is no viable transportation option to remove the items for destruction elsewhere in the Republic of Panama or outside of the Republic of Panama. -

The German Wehrmacht in Wwii: Knight’S Cross Holders, Biogra Phies & Memoirs

62 U.S. & ALLIES FROM WWI TO THE PRESENT • THE GERMAN WEHRMACHT IN WWII: KNIGHT’S CROSS HOLDERS, BIOGRA PHIES & MEMOIRS Heroes of Our Time: 239 Men of the Vietnam Along the Tigris: The 101st Airborne Division The Knight’s Cross with Oakleaves, 1940- War Awarded the Medal of Honor 1964-72 in Operation Iraqi Freedom Thomas L. Day. The 1945: Biographies and Images of the 889 Kenneth N. Jordan. Heroes of Our Time contains all story of 16,000 soldiers, from the training grounds of Recipients Jeremy Dixon. This two-volume set 239 Medal of Honor citations, along with the citations Fort Campbell, through the toughest battles in the blitz presents every recipient of the Knight’s Cross with are newspaper accounts of various battles. of Baghdad to the Nineveh province, where the 101st Oakleaves, awarded during WWII, and presented by Size: 6"x9" • 30 bw photos • 368pp. Airborne Division anchored for eight months after the Hitler from 1940 until 1945. Included are each of the ISBN: 0-88740-741-2 • hard • $24.95 overthrow of Saddam Hussein. 889 recipients from the Luftwaffe, Heer, Waffen-SS, Size: 6"x9" • 150 color photos • 400pp. and Kriegsmarine, as well as foreign recipients. This ISBN: 0-7643-2620-2 • hard • $35.00 is the fi rst time such a work is in English. Size: 8.5"x11" • 1000 color/bw photos • 648pp. ISBN: 978-0-7643-4266-0 • hard cover, two-volume THE GERMAN WEHRMACHT IN WWII set in deluxe slipcase • $125.00 • Schiffer LTD Men of Honor: Thirty-Eight Highly Decorated Knight’s Cross Holders of the Fallschirmjäger: Marines of WWII, Korea and Vietnam Kenneth KNIGHT’S CROSS HOLDERS, BIOGRAPHIES & MEMOIRS Hitler’s Elite Parachute Force at War, 1940-1945 N.