Comment on Brian Martin's Article “Bad Social Science”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autism and MMR Vaccine Study an 'Elaborate Fraud,' Charges BMJ Deborah Brauser Authors and Disclosures

Autism and MMR Vaccine Study an 'Elaborate Fraud,' Charges BMJ Deborah Brauser Authors and Disclosures January 6, 2011 — BMJ is publishing a series of 3 articles and editorials charging that the study published in The Lancet in 1998 by Andrew Wakefield and colleagues linking the childhood measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine to a "new syndrome" of regressive autism and bowel disease was not just bad science but "an elaborate fraud." According to the first article published in BMJ today by London-based investigative reporter Brian Deer, the study's investigators altered and falsified medical records and facts, misrepresented information to families, and treated the 12 children involved unethically. In addition, Mr. Wakefield accepted consultancy fees from lawyers who were building a lawsuit against vaccine manufacturers, and many of the study participants were referred by an antivaccine organization. In an accompanying editorial, BMJ Editor-in-Chief Fiona Godlee, MD, Deputy BMJ Editor Jane Smith, and Associate BMJ Editor Harvey Marcovitch write that there is no doubt that Mr. Wakefield perpetrated fraud. "A great deal of thought and effort must have gone into drafting the paper to achieve the results he wanted: the discrepancies all led in 1 direction; misreporting was gross." A great deal of thought and effort must have gone into drafting the paper to achieve the results he wanted: the discrepancies all led in 1 direction; misreporting was gross. Although The Lancet published a retraction of the study last year right after the UK General Medical Council (GMC) announced that the investigators acted "dishonestly" and irresponsibly," the BMJ editors Dr. -

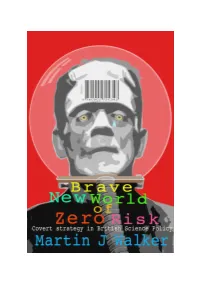

Brave New World of Zero Risk: Covert Strategy in British Science Policy

Brave New World of Zero Risk: Covert Strategy in British Science Policy Martin J Walker Slingshot Publications September 2005 For Marxists and neo liberals alike it is technological advance that fuels economic development, and economic forces that shape society. Politics and culture are secondary phenomena, sometimes capable of retarding human progress; but in the last analysis they cannot prevail against advancing technology and growing productivity. John Gray1 The Bush government is certainly not the first to abuse science, but they have raised the stakes and injected ideology like no previous administration. The result is scientific advisory panels stacked with industry hacks, agencies ignoring credible panel recommendations and concerted efforts to undermine basic environmental and conservation biology science. Tim Montague2 A professional and physician-based health care system which has grown beyond tolerable bounds is sickening for three reasons: it must produce clinical damages which outweigh its potential benefits; it cannot but obscure the political conditions which render society unhealthy; and it tends to expropriate the power of the individual to heal himself and to shape his or her environment. Ivan Illich3 Groups of experts, academics, science lobbyists and supporters of industry, hiding behind a smoke screen of `confidentiality' have no right to assume legislative powers for which they have no democratic mandate. The citizens and their elected representatives are ethically competent to democratically evaluate and shape their own future. Wilma Kobusch4 1 The New Yorker. Volume 52, Number 13 · August 11, 2005. John Gray, ‘The World is Round’. A review of The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-first Century by Thomas L. -

The Write Stuff the Journal of the European Medical Writers Association

wstuf0605-pp.qxp 27.6.2005 12:59 Page 1 The Write Stuff The Journal of the European Medical Writers Association Greetings from Malta www.emwa.org Vol. 14, No.3, 2005 wstuf0605-pp.qxp 27.6.2005 12:59 Page 2 The Write Stuff 77tthh AAuuttuummnn MMeeeettiinngg Radisson Edwardian Hotel, Manchester, UK. Your Executive Committee has the pleasure of inviting you to the 7th autumn meeting in sunny Manchester on the 24th to the 26th of November 2005. Originally founded in the 1st century by the Romans and named Mamucium, Manchester became a city of renown during the industrial revolution at which time it was consid- ered the heart of the British Empire. As a thriving metrop- olis, which still produces more than half of Britain's manu- factured goods and consumables, Manchester has acquired a mixed reputation. However, recent international events of some acclaim, such as the success of Manchester United, the 2002 Commonwealth Games and the soon to be held EMWA Autumn Conference are raising the profile of the city. Our conference will be located at the Radisson Edwardian. A hotel ideally suited to combine the learning and network- ing opportunities available at the EMWA meetings with the cultural delights Manchester has to offer. The programme of workshops will cover many aspects of medical writing, and will also include some of our new Advanced workshops. Keep an eye on our website (www.emwa.org) for regular updates and further details. If you are looking for premier educational experiences for medical communicators the Manchester meeting holds great promise with the added attraction of discovering what the city has to offer. -

Rising Tide of Plagiarism and Misconduct in Medical Research

telephone +1 (510) 764-7600 email [email protected] web WWW.ITHENTICATE.COM RISING TIDE OF PLAGIARISM AND MISCONDUCT IN MEDICAL RESEARCH 2013 iThenticate Paper Summary Plagiarism and other forms of misconduct are a growing problem in research. When factored for the increase in articles published, there has been a 10 fold increase in the rate of article retraction over the past 20 years. A quarter of those retractions are due to plagiarism and duplication, often referred to as self-plagiarism, and a larger portion of retractions are fraudulent or fabricated work. Unfortunately, this rise in unethical research is having severe consequences on the medical profession. Not only is money and time being wasted trying to replicate questionable research, precious publication space is also wasted on duplicative papers. More importantly, the ethical issues are beginning to increasingly impact the level of trust that the public puts into the medical profession. Even worse, patients sometimes receive ineffective or harmful treatments based on poor or unethical research. Although there are many potential solutions, there is no single floodgate to restraining misconduct in medical research. Stemming the tide of bad research will require a concerted effort at all levels and roles in the field of medical research—from the researchers that pen new papers to the journals themselves and even the doctors who receive the final publications. Without addressing the issue directly and broadly, the issue and its consequences are only likely to grow. Introduction: The Rise of Plagiarism In the December 2010 issue of the journal Anesthesia and Analgesia, the editor of the publication posted a notice of retraction, stating that they had become aware that a recently published manuscript entitled “The effect of celiac plexus block in critically ill patients intolerant of enteral nutrition: a randomized, placebo- controlled study” had portions of it found to be plagiarized from five other manuscripts. -

On the Suppression of Vaccination Dissent Brian Martin University of Wollongong, [email protected]

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts 2015 On the suppression of vaccination dissent Brian Martin University of Wollongong, [email protected] Publication Details Martin, B. (2015). On the suppression of vaccination dissent. Science and Engineering Ethics, 21 (1), 143-157. Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] On the suppression of vaccination dissent Abstract Dissenters from the dominant views about vaccination sometimes are subject to adverse actions, including abusive comment, threats, formal complaints, censorship, and deregistration, a phenomenon that can be called suppression of dissent. Three types of cases are examined: scientists and physicians; a high-profile researcher; and a citizen campaigner. Comparing the methods used in these different types of cases provides a preliminary framework for understanding the dynamics of suppression in terms of vulnerabilities. Keywords vaccination, dissent, suppression Disciplines Arts and Humanities | Law Publication Details Martin, B. (2015). On the suppression of vaccination dissent. Science and Engineering Ethics, 21 (1), 143-157. This journal article is available at Research Online: http://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers/1883 On the suppression of vaccination dissent Published in Science & Engineering Ethics, Vol. 21, No. 1, 2015, pp. 143-157; doi 10.1007/s11948-014-9530-3 Brian Martin Go to Brian Martin's publications on vaccination Brian Martin's publications Brian Martin's website Abstract Dissenters from the dominant views about vaccination sometimes are subject to adverse actions, including abusive comment, threats, formal complaints, censorship, and deregistration, a phenomenon that can be called suppression of dissent. -

Wetenschappelijke Integriteit Lessen 2019-2020

DEPARTMENT HEALTH INNOVATION AND RESEARCH INSTITUTE GHENT UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL WETENSCHAPPELIJKE INTEGRITEIT Prof. Dr. Catherine Van Der Straeten, MD, PhD, FIOR Diensthoofd Health Innovation & Research Institute UZ Gent DEFINITIE WETENSCHAPPELIJKE INTEGRITEIT: FWO • niet helemaal hetzelfde als onderzoeksethiek. • Integriteit: aspecten van kwaliteit van de wetenschapspraktijk en haar resultaten. • Ethiek: normen en waarden met het oog op welzijn van mensen en dieren in het onderzoek en de resultaten daarvan. e.g. data vervalsen, zonder onmiddellijk mens of dier in gevaar te brengen: = geen integere wetenschap, resultaten zijn onbetrouwbaar direct onethisch gedrag tegenover mens, dier en hun milieu. • Het toepassen van die gemanipuleerde resultaten kan uiteindelijk toch mensen, dieren en hun omgeving schaden: integriteit en ethiek nooit volstrekt te scheiden. • In de ruime betekenis van ethiek is vervalsen van onderzoeksresultaten of knoeien met wetenschap onaanvaardbaar. Wetenschappelijke integriteit is dus te beschouwen als een bijzondere dimensie van wetenschappelijke ethiek. 2 UGENT 3 SCIENTIFIC INTEGRITY: DEFINITIE KUL Scientific or academic integrity = conducting scientific research in a careful, reliable, controllable, reproducible, repeatable, objective, neutral, independent way. Authenticity is of great importance. Principles of scientific integrity: • integrity of authorship • correct citing of peers • mentioning acknowledgements • mutual respect, e.g. equal contribution in group work • transparency • veracity Replication MiniMise -

1 Wakefield's Article Linking MMR Vaccine and Autism Was Fraudulent

Wakefield’s article linking MMR vaccine and autism was fraudulent 1. Fiona Godlee, editor in chief, 2. Jane Smith, deputy editor, 3. Harvey Marcovitch, associate editor Author Affiliations: BMJ, London, UK 1. Correspondence to: F Godlee [email protected] Clear evidence of falsification of data should now close the door on this damaging vaccine scare “Science is at once the most questioning and . sceptical of activities and also the most trusting,” said Arnold Relman, former editor of the New England Journal of Medicine, in 1989. “It is intensely sceptical about the possibility of error, but totally trusting about the possibility of fraud.”1 Never has this been truer than of the 1998 Lancet paper that implied a link between the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine and a “new syndrome” of autism and bowel disease. Authored by Andrew Wakefield and 12 others, the paper’s scientific limitations were clear when it appeared in 1998.2 3 As the ensuing vaccine scare took off, critics quickly pointed out that the paper was a small case series with no controls, linked three common conditions, and relied on parental recall and beliefs.4 Over the following decade, epidemiological studies consistently found no evidence of a link between the MMR vaccine and autism.5 6 7 8 By the time the paper was finally retracted 12 years later,9 after forensic dissection at the General Medical Council’s (GMC) longest ever fitness to practise hearing,10 few people could deny that it was fatally flawed both scientifically and ethically. But it has taken the diligent scepticism of one man, standing outside medicine and science, to show that the paper was in fact an elaborate fraud. -

Apresentação Do Powerpoint

Por que falar de conduta científica? Prof. Maria Carlota Rosa Seminários do Programa de Linguística: Sobre Ética e Integridade na Formação de Pesquisadores - edição2017 Definindo “má conduta científica” Entende-se por má conduta científica toda conduta de um pesquisador que, por intenção ou negligência, transgrida os valores e princípios que definem a integridade ética da pesquisa científica e das relações entre pesquisadores [....]. A má conduta científica não se confunde com o erro científico cometido de boa fé nem com divergências honestas em matéria científica. (FAPESP, 2011) A violação da ética na pesquisa pode-se dar de modos diferentes e em estágios diferentes do trabalho, os mais frequentes resumidos na sigla FFP, iniciais das palavras • Fabricação; • Falsificação; • Plágio. 3 BIRD & DUSTIRA, 2000 Todas las ramas de la ciencia tienen sus falsarios. Sin embargo, los fraudes son más frecuentes en aquellas disciplinas relacionadas con la vida, quizás por la importancia crematística, la siempre difícil reproducibilidad por diferencias biológicas y por el componente emocional cuando se trata de tratamientos milagrosos, que oscurece el raciocinio de quienes se encuentran incluidos directamente, los pacientes estafados. Rama-Maceiras, Ingelmo Ingelmo, Fàbregas Julià & Hernández-Palazón 2009 Se um trabalho está publicado num periódico com avaliação por pares e alto fator de impacto (FI), o pressuposto é que deve ser bom, isto é, CONFIAMOS que deve, pelo menos: • ser inovador e relevante, • ter metodologia aceita, • fornecer evidências para a hipótese e • deve basear-se numa pesquisa executada sem violações da ética. in a community based on trust, how do you find a reasonable balance of trust and skepticism? Where are the lines? GUNSALUS & RENNIE [2015] A credibilidade de um trabalho científico 1º - Autoria: de quem é o trabalho? • Segundo a FAPESP (2011) 2.2.3. -

The Doctor Who Fooled the World. Andrew Wakefield's War on Vaccines

Life & Times Books: long read The Doctor Who Fooled The World. glazed eyes. In my first years as a GP I was related the measles vaccine to autism via Andrew Wakefield’s War On Vaccines tasked to raise the childhood immunisation a new ‘inflammatory bowel disease’. When Brian Deer from ‘What? How do you mean?’ to the 94% others contradicted his results he devised Scribe Publications, 2020, PB, 416pp, £16.99, which we — the staff, the health visitors and invalid tests performed in laboratories he 978-1911617808 myself — achieved. owned. For reasons of medical politics My two children were fully immunised and alone he was given an expensively furnished I ensured they got the second MMR when it and equipped research ward supported by was proven to be needed. I, like the majority, those who wanted to promote their own looked on immunisation as an example of progression and, as a ‘research assistant’. modern living and progress ... and then, with He became ‘a doctor without patients’, able age and experience only a couple of years to admit and investigate 12 children selected less than mine, came Andrew Wakefield. because their parents had heard of him through ‘Jabs’ (a support group for vaccine- WAKEFIELD DEVISED INVALID TESTS damaged children). PERFORMED IN LABORATORIES HE For those in primary care, we need to OWNED remember that these children had referral Brian Deer has described Wakefield in the letters from GP’s, but in most cases the GP I LOOKED ON IMMUNISATION AS AN terms he deserves. Born into a medical was phoned by Wakefield requesting the referral, or the parent asked the GP for the EXAMPLE OF MODERN LIVING AND family, at medical school he was a captain referral prompted by talking to Wakefield. -

Final Zero Checked 2

Brave New World of Zero Risk: Covert Strategy in British Science Policy Martin J Walker Slingshot Publications October 2005 Brave New World of Zero Risk: Covert Strategy in British Science Policy Martin J. Walker First published as an e-book, October 2005 © Slingshot Publications, October 2005 BM Box 8314, London WC1N 3XX, England Type set by Viviana D. Guinarte in Book Antiqua 11/12, Verdana Edited by Rose Shepherd Cover design by Andy Dark In this downloadable Pdf form this book is free and can be distributed by anyone as long as neither the contents or the cover are changed or altered in any way and that this condition is imposed upon anyone who further receives or distributes the book. In the event of anyone wanting to print hard copies for distribution, rather than personal use, they should consult the author through Slingshot Publications. Selected parts of the book can be reproduced in any form, except that of articles under the author’s name, for which he would in other circumstances receive payment; again these can be negotiated through Slingshot Publications. More information about this book can be obtained at: www.zero-risk.org For Marxists and neo liberals alike it is technological advance that fuels economic development, and economic forces that shape society. Politics and culture are secondary phenomena, sometimes capable of retarding human progress; but in the last analysis they cannot prevail against advancing technology and growing productivity. John Gray1 The Bush government is certainly not the first to abuse science, but they have raised the stakes and injected ideology like no previous administration. -

CHIROPRACTIC Back Manipulation As Gene Therapy—How the Oddest Idea Went Global, by Steve Salzberg

January 2012 issue 84 rearranged:Layout 1 15/01/2012 15:12 Page 1 access our website on http://w w w.healthwatch-uk.org Registered Charity no. 1003392 HealthWatch Established 1992 for treatment that works Newsletter 84 January 2012 AWARDS AND AN ANNIVERSARY T THE 19TH HealthWatch annual general meeting there were even more winners than in previous years. This year’s special award for contributing to the public’s understanding of health issues went to Brian Deer, the medical journalist who exposed the MMR scandal (read his report of his presentation on pages 4 and 5 of this issue). It was also the tenth anniversary of the AHealthWatch student prize for critical appraisal of clinical trial protocols. A very special award was reserved for the HealthWatch founder steel spoon engraved with his initials and the message “evidence: member, many-times chairman and most prolific contributor to the one spoonful daily” (John reports again in this issue, page 8). HealthWatch Newsletter—John Garrow. In recognition of his long This year’s student competition, which invites entrants to rank and valued service, the committee presented him with an over-sized and critique various trial protocols, attracted a record number of entries. First prize for 2011 went to 23-year-old Derek Ho, origi - nally from Hong Kong, who is in his fifth year at London’s Imperial College Medical School planning to specialise in ophthalmology or surgery. He entered the HealthWatch competition hoping just to practise his analytical skills during the summer holiday, so was delighted to discover that he had won first prize. -

Andrew Wakefield Has Never Been Exonerated: Why Justice Mitting's

Expert Commentary Series Andrew Wakefield Has Never Been “Exonerated”: Why Justice Mitting’s Decision in the Professor John Walker-Smith Case Does Not Apply to Wakefield By Joel A. Harrison, PhD, MPH August 1, 2016 Note. For those interested in investigating the complete story, including documentation, see the following (all accessed on June 28, 2016): Brian Deer: “Wakefield & MMR: how a worldwide health scare was launched from London” at: http://briandeer.com/mmr/wakefield-archive.htm ) Brian Deer: the Lancet scandal at: http://briandeer.com/mmr-lancet.htm Brian Deer: the Wakefield factor at: http://briandeer.com/wakefield-deer.htm Brian Deer: Solved - the riddle of MMR at: http://briandeer.com/solved/solved.htm Brian Deer: Secret of the MMR scare at: http://briandeer.com/solved/bmj-secrets- series.htm Brian Deer: [Summary of Investigation] Exposed: Andrew Wakefield and the MMR- autism fraud at: http://briandeer.com/mmr/lancet-summary.htm Unfortunately, many people will read what antivaccinationists write about Brian Deer and what he wrote without taking the time and effort to actually investigate for themselves. For those interested, through the UK Freedom of Information Act, the complete transcript of the UK General Medical’s Fitness to Practice Panel’s three year hearing has been made available on the Internet in two versions, one in day order and one grouped by type and name of witness, allowing one to carry out specific searches (Accessed June 28, 2016) at: General Medical Council: Transcripts: Grouped at: http://sheldon101blog.blogspot.com/p/grouped-wakefield-transcripts.html General Medical Council: Transcripts: Day Order at: http://sheldon101blog.blogspot.com/p/day-order-wakefield-transcripts.html https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B9Ek8hRNlhrbNTk4MWI5YjktMDU3MS00M WU1LWFiZjQtZjA3MzI0ZDM0NTBl/view?hl=en&pref=2&pli=1 1 Introduction On March 7, 2012, Mr.