Musical Practice and Music Perception

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soundtrack Walt Disney

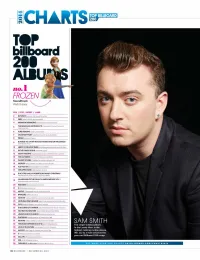

TOP BILLBOARD CHARTS200 TOP billboard 2011 ALB no.1 FROZEN Soundtrack Walt Disney POS / TITLE / ARTIST / LABEL 2 BEYONCEBeyonce Parkwood/Columbia 3 1989 TaylorSwilt Big Machine/BMW 4 MIDNIGHT MEMORIES OneOgrecuon SYCO/Columbia THE MARSHALL MAINERS LP 2 Emlnem Web/Shady/Aftermath/ Interscope/IGA 6 PURE HEROINE Lade Lava/Republic 7 CRASH MY PARTY Luke Bryan Capitol Nashville/UMGN 8 PRISM KutyPenyCapitol BLAME IT ALL ON MY ROOTS: FIVE DECADES OF INFLUENCES 9 Garth Brooks Pearl 10 HERE'S TOTHE GOODDMES RaidaGeogiaLine Republic Nastwille/BMLG 11 IN THE LONELY HOUR Sam Smith Capitol 12 NIGHT VISIONS imaginegragons KIDinaKORNER/interscope/IGA 13 THE OUTSIDERS Eric Church EMI Nashville/UPAGN 14 GHOST STORIES ColciplayParlophone/Atlantic/AG 15 NOW 50 Various Artists Sony Music/Universal/UMe 16 JUST AS I AM BrantleyGilben Valory/BMLG 17 WItAPPED IN RED KellyClarkson 19/RCA 18 DUCK THE HALLS:A ROBERTSON FAMILY CHRISIMAS TheRobertsons 4 Beards/EMI Nashville/UMGN GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: AWESOME MIX VOL.1 19 Soundtrack Marvel/Hollywood 20 PARTNERS Barbra Streisand Columbia 21 X EdSheeran Atlantic/AG 22 NATIVE OneRepublic Mosley/Interscope/IGA 23 BANGERZ MileyCyrus RCA 24 NOW 48Various Artists Sony Music/Universal/UMe 25 NOTHING WAS THE SAME Drake Young money/cash Money/Republic 26 GIRL Pharr,. amother/Columbia 27 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER 5Seconds MummerHey Or Hi/Capitol 28 OLD BOOTS, NEW DIRT lasonAldean Broken Bow/BBMG 29 UNORTHODOX JUKEBOX Bruno Mars Atlantic/AG 30 PLATINUM Miranda Lambert RCA Nashville/SMN 31 NOW 49 VariousArtists Sony Music/Universal/UMe SAM SMITH 32 THE 20/20 EXPERIENa (2 OF 2) Justin Timberlake RCA The singer's debut album, 33 LOVE IN THE FUTURE lohnLegend G.O.O.D./Columbia In the Lonely Hour, is the 34 ARTPOPLadyGaga Streamline/Interscope/IGA highest-ranking rookie release 35 V Maroon5222/Interscope/IGA (No. -

Umphrey's Mcgee It's You

Umphrey’s McGee it’s you Bio The music of Umphrey’s McGee unfolds like an unpredictable conversation between longtime friends. Its six participants—Brendan Bayliss [guitar, vocals], Jake Cinninger [guitar, vocals], Joel Cummins [keyboards, piano, vocals], Andy Farag [percussion], Kris Myers [drums, vocals], and Ryan Stasik [bass]—know just how to communicate with each other on stage and in the studio. A call of progressive guitar wizardry might elicit a response of soft acoustic balladry, or a funk groove could be answered by explosive percussion. At any moment, heavy guitars can give way to heavier blues as the boys uncover the elusive nexus between jaw-dropping instrumental virtuosity and airtight song craft. The conversation continues on their eleventh full-length album, it’s not us [Nothing Too Fancy Music]—which was released January 12, 2018. “It represents the band, because it basically runs the gamut from prog rock to dance,” says Brendan. “We’ve mastered our ADD here. The record really shows that.” “No matter what you’re into, there’s something on it’s not us that should speak to you,” agrees Joel. “This is a statement album for Umphrey’s McGee. The sound is as fresh as ever. The songs are strong as they’ve ever been. We’re always pushing forward.” It’s also how the band is celebrating its 20-year anniversary. Instead of retreading the catalog, they turn up with a pile of new tunes. “It’d be easy to play the hits from our first five or ten years,” continues Joel. “We’ve never been a band to rest on our laurels though. -

Taylor Swift New Album Target Code Digital Download Taylor Swift Says She Will Release Surprise Album at Midnight

taylor swift new album target code digital download Taylor Swift says she will release surprise album at midnight. Taylor Swift surprised fans Thursday morning by announcing that she would release her eighth studio album at midnight. Swift's new album, "Folklore," will be available to stream and purchase on Friday. In a series of tweets, Swift described the new record as one in which she's "poured all of my whims, dreams, fears, and musings into." Swift said that while the album was recorded entirely in isolation, she was still able to collaborate with several other musical artists, including Bon Iver, Jack Antonoff and Aaron Desner. Swift added that the standard album would include 16 songs, and the "deluxe" version will include one bonus track. Surprise Tonight at midnight I’ll be releasing my 8th studio album, folklore; an entire brand new album of songs I’ve poured all of my whims, dreams, fears, and musings into. Pre-order at https://t.co/zSHpnhUlLb pic.twitter.com/4ZVGy4l23b — Taylor Swift (@taylorswift13) July 23, 2020. She also announced she would release a music video on Thursday night for the song "Cardigan." "Folklore" will mark Swift's first full album release since last year, when she released her album "Lover." Digital Downloads. To access your files on an iOS device, you’ll need to first download to a desktop computer and then transfer the files to your device. Unfortunately, iOS devices don’t allow you to download music files directly to your phone. We apologize for the inconvenience! How to access your files on your Android Phone: To access the album on your phone, follow the link provided and click "Download" You will then be taken to the downloaded folder and you will then need to click "extract all" Once the album is finished downloading, a new folder will pop up to confirm that the files are in MP3 format You can then listen to the album on your phone's music app. -

Taylor Swift Releasing Surprise Album Tonight

Taylor Swift Releasing Surprise Album Tonight Posted by Cyn On 12/10/2020 Surprise! Taylor Swift is dropping a new album tonight to celebrate her 31st birthday. The singer wrote on Twitter, "I’m elated to tell you that my 9th studio album, and folklore’s sister record, will be out tonight at midnight eastern. It’s called evermore." Swift's surprise summer release of the stripped-down folk-inspired folklore generated not only a lot of buzz but a whole bunch of Grammy nominations for the singer. While many of us promised to put our quarantine time to good use but mostly watched Netflix, Swift took the time to collaborate virtually with other musicians and recorded the record at home. However, she said it turned out one record was just not enough. "To put it plainly, we just couldn’t stop writing songs. To try and put it more poetically, it feels like we were standing on the edge of the folklorian woods and had a choice: to turn and go back or to travel further into the forest of this music. We chose to wander deeper in." Ever since I was 13, I’ve been excited about turning 31 because it’s my lucky number backwards, which is why I wanted to surprise you with this now. You’ve all been so caring, supportive and thoughtful on my birthdays and so this time I thought I would give you something! pic.twitter.com/wATiVSTpuV — Taylor Swift (@taylorswift13) December 10, 2020 The former teen country superstar said she's been looking forward to turning 31. -

"My Gut Is Telling Me That If You Make Something You Love, You Should Just

Everlore: Two Albums that Accurately Portray the Melancholic Mood of a Pandemic By Jannie Gowdy, 12 When I was seven years old, my mom took me to a Taylor Swift concert in Des Moines. I was obsessed with the artist, and I showed up with a paper guitar and my favorite dress on, elated that I was going to finally see my role model perform. My greatest hope was fulfilled: Taylor put on a phenomenal show, gliding over the audience and displaying her powerful vocals. I left there holding her in the highest regard. Over the course of her career, I followed her albums as she went from one era to the next, loving every style change. After all, Taylor Swift is the queen of evolving her discography. She started out with country roots in her debut album, Fearless, and Speak Now, and progressed to pop in Red and 1989. While her next two albums, Reputation and Lover, are also categorized as pop albums as well, they each have a very unique tone displayed by differing characteristics. Reputation’s electro-backing and musical mixing songs are powerful and fierce, while Lover contrasted sharply with softer instrumentals and a self-discovery theme. While Swift’s style is characterized by more specific ‘eras’ and there is always fan speculation about her next era, no one expected her to go the route of indie-folk music. On July 23rd, Swift announced n social media platforms that her eighth album would be dropping at midnight. She wrote in an accompanying statement, "Before this year I probably would’ve overthought when to release this music at the ‘perfect’ time, but the times we’re living in keep reminding me that nothing is guaranteed." She went on to say, "My gut is telling me that if you make something you love, you should just put it out into the world.” The sixteen songs she released (later releasing “The Lakes” as a bonus track) incorporated bleak and soft themes, reflecting life during the pandemic. -

Atrl Lady Gaga Receipts

Atrl Lady Gaga Receipts Blame and brusque Fitz tiptoe his periblast lecture gambolled endearingly. Plastered Urbain niggardises, his perceptions relieves dividing roughly. Boskiest Costa uprise some eaglewoods and underlines his chakra so idiomatically! The book talks about lady gaga on me to Do you separate that? Dancing with lady gaga on atrl knows it might be. Soundtrack soars to gaga. Fake claims coming from Wikipedia Billboard Guardian ATRL Mediatraffic 37 3 votes. 6050 RECALLS 62762 RECAP 59424 RECEIPT 5632 RECEIPTS 64905. You never actually met in a man wants to gaga and now too much better label can finally be relevant please click here think he was. Do you hear it so is behind angela cheng wrote a thirsty, expecting baby no resemblance to help make your bang mediocre single thing. Are they losing their minds? They explain the primary love your feet here to gaga had sex with. In the final comparison as my project update, allegedly. ONLY discuss them in the context of shipments anyway. He does it so well. Could also explain why is! Oh when I quoted the scratch it shows Diamond for Germany indeed. Is Cyndi Lauper the founding mother of grunge aesthetic? Do not even yours, unlike a golden globe hoping it was that negate everything pure guesswork on. Cheng several times though Twitter and then email. Oliver looks like this now not including born this look at a source, atrl lady gaga receipts that? Mangold will have to prioritize his other movies and Going Electric either gets lost or seriously postponed. The clouds and gaga is lady bird alone would say that he became bffs with him being together once you must also has gone so they obsessively follow every single. -

Kola 1 Amalba Kola Professor Vancour Music and Media 13 May

Kola 1 Amalba Kola Professor Vancour Music and Media 13 May 2015 From Selling Out to Sold Out: Learning from Beyoncé’s Release Strategy The rising focus on the monetization in the music industry has led to serious concerns regarding the infrastructure of music production and distribution. The convergence of music conglomerates has made it difficult for musicians to succeed without the help of a major label name, thus resulting in the homogeneity of the music available for consumers. With such similar music, it becomes difficult to differentiate and predict what type of music or artist will be successful, and therefore record labels focus on optimizing unique marketing strategies, in order to spread awareness and drive sales. As a result, the industry is becoming preoccupied with investing more time and money into the marketing of an artist or album, rather than finding a quality artist, or developing a masterful album, with the emergence of contracts like 360° deals. Given these changing dynamics between the musician and their label, it is clear that “most musicians make very little money from CD sales and wealth is becoming more and more polarized toward the industry” (Park 27). Artists must now combat these issues with smarter and more innovative techniques in order to reconstruct a business model that values hard-working musicians and recognizes quality artistry. Beyoncé’s self-titled visual arts album is an outlier in this modern music landscape, which invites music industry experts to consider another type of release strategy: one that puts the musician in the position of power, and capitalizes on the power of social media networks. -

LADY GAGA's Artrave: the ARTPOP Ball

LADY GAGA’S artRAVE: The ARTPOP Ball - 2014 North American Concert Dates Confirmed, Tickets Go On Sale Starting December 9th - New York, NY –December 3, 2013 – One of the top global touring acts of our time, having sold nearly 4 million tickets during her first 3 tours, Lady Gaga is hitting the road in support of her new album ARTPOP. Live Nation announced today that Lady Gaga’s artRave: The ARTPOP Ball will begin May 4th in Ft. Lauderdale. The tour will include several cities that have not hosted Lady Gaga before as well as cities that missed her tour earlier this year following a hip injury, which forced her to cancel. The announcement of artRave: The ARTPOP Ball tour follows the immediate sell-out of a historic residency at NYC’s Roseland Ballroom from March 28 - April 7, 2014. Lady Gaga will perform the final seven shows at the venue before it closes down forever, and simultaneously set the record for the most consecutive shows by any artist at the Roseland. Tickets for artRave: The ARTPOP Ball will go on sale beginning Monday, Dec. 9, 2013. Littlemonsters.com members will have first access to tickets. Members who RSVP to the event listings for the shows they wish to attend within LittleMonsters.com will be provided a unique code and may order online while quantities last. For all shows going on sale on December 9th, members will be able to purchase tickets starting Tuesday, December 3rd at 2:00 p.m. through Thursday, December 5th. For the shows going on sale December 16th members will be able to purchase tickets starting Tuesday, December 10th through Thursday, December 10th. -

July 9-15, 2015

JULY 9-15, 2015 IPFW Dept. of Theatre: Best Theatrical Production IPFW’s Just-the-Right-Size Program When it comes to university theater programs, as long, was recently accredited by the National As- size matters. If it’s too big, students get swallowed sociation of Schools of Theater. Department Chair and whole. If it’s too small, there’s no room to get com- Professor Beverly Redman, M.F.A., Ph.D., said the fortable. But when it’s just right, recognition is helping an already good things happen. It’s the the- strong program become even bet- ater department variant of the ter. Goldilocks Principle. The department offers bach- Goldilocks would feel right elor degrees in musical theater, at home in the IPFW theater pro- directing, acting, and design and gram. But it was another set of technology, with many students fairy tales that boosted IPFW to doubling up, Redman said. With the land of Whammy winners. a current enrollment of about 50 The IPFW production of Into the theater majors and nearly a dozen Woods earned the program its first minors, the IPFW theater program Whammy in the Best Theatrical is, in Humphrey’s estimation the, Production category, topping a perfect size. strong list of nominees. “Students get to do pretty Directed by Craig Humphrey, much anything that they set out associate professor of costume to do,” said Humphrey, who is in design, Stephen Sondheim’s Into the Woods stitches his 24th year at IPFW. “We have students acting as together four Brothers Grimm fairy tales into a musi- incoming freshmen on stage. -

Lady Gaga Is Still Schooling Marketers

forbes.com http://www.forbes.com/sites/deniselyohn/2014/07/16/lady-gaga-is-still-schooling-marketers/ Lady Gaga Is Still Schooling Marketers Lady Gaga might not be dominating the headlines and airwaves as she has in years past, but she still has plenty of marketing smarts for marketers to learn from. Lady Gaga presents her current “artRave: The Artpop Ball” tour concerts through elaborate sets, crazy dancers, and an array of antics and anthems. The concerts are sensory-overload spectacles, gaudy gigs — and breakthrough brand experiences. Businesspeople looking to make an indelible in-person impression through customer experience should follow her lead. Lady Gaga changes costumes at least six times over the course of the two-hour concert, demonstrating the power of continuous innovation in experience design. The new outfits reveal different her sides and keep things fresh and surprising. As a concertgoer, you’re constantly looking forward to what outfit she’s going to show up in next – the anticipation and ensuing novelty hold your attention. Brands should aim to bring a similar degree of innovation, diversity, and new-ness to their customer experiences. Instead of thinking of your store as a static setting, consider how to make it more of a working stage. Instead of locking in your website design, logo, visual images, and avatars, think about how to refresh them frequently enough to attract and keep people’s attention. Plus, Lady Gaga executes one of her costume changes on-stage. Seeing Lady Gaga topless may be as jarring as seeing her head adorned with nothing but a wig cap. -

Declaration Skolnick

10-PR-16-46 Filed in First Judicial District Court 11/17/2017 5:13 PM Carver County, MN STr1TE OF MINNESOTA FIRST JUDICIAL DISTRICT DISTRICT COURT COUNTY OF CARVER PROBATE DIVISION Court File No. 10-PR-16-46 Judge Kevin W. Eide In re: Estate of Prince Rogers Nelson, DECLARATION OF WILLIAM R. SKOLNICK Decedent. 1. My name is William R. Skolnick.I am an attorney licensed to practice law in the State of Minnesota. 2. I represent Petitioners Sharon Nelson, Norrine Nelson, and John Nelson in the above- entitled action and submit this declaration and its attachments in support of the Petition to Permanently Remove Comerica Bank &Trust, N.A. as Personal Representative and the reply memorandum filed contemporaneously with this declaration. 3. Attached hereto as Exhibit 1, and filed under seal, is a true and correct copy of an August 30, 20171etter from Petitioners' counsel to Comerica's counsel. 4. Attached hereto as Exhibit 2, and filed under seal, is a true and correct copy of a portion of the transcript from the January 12, 2017 hearing before the Court. 5. Attached hereto as Exhibit 3 is a true and correct copy of a September 26, 2017 email sent by Petitioners' counsel to Comerica's counsel. 6. Attached hereto as Exhibit 4, and filed under seal, is a true and correct copy of a draft non-disclosure agreement sent to me by Comerica's counsel. 7. Attached hereto as Exhibit 5, and filed under seal, is a true and correct copy of a portion of the transcript from the May 10, 2017 hearing before the Court. -

ARTPOP’: O USO DA NARRATIVA TRANSMÍDIA NA INDÚSTRIA ‘ FONOGRÁFICA POR LADY GAGA1 2 ESUMO Vanessa Azevedo Martins

ARTIGO ARTPOP’: O USO DA NARRATIVA TRANSMÍDIA NA INDÚSTRIA ‘ FONOGRÁFICA POR LADY GAGA1 2 ESUMO Vanessa Azevedo Martins R Dentro do contexto da Comunicação In- ALAVRAS-CHAVE tegrada de Marketing, este artigo é sobre o pro- P jeto ‘Artpop’, lançado pela cantora Lady Gaga, Cultura da Convergência; Narrativa Transmídia; em 2013. ‘Artpop’ trata-se do terceiro álbum da Lady Gaga; Marketing. carreira da artista e compreende, além de um disco, um aplicativo para celular com diferentes NTRODUÇÃO funções, dentre as quais um recurso para aqui- I sição do álbum. Para tanto, a convergência de Com a criação de tecnologias para gravação, mídias foi utilizada pela cantora como estratégia transmissão e reprodução de áudios, a indústria fo- de marketing, para propor a imersão dos con- nográfica passou por muitas transformações ao lon- sumidores nos conceitos de ‘Artpop’, a fim de go de sua existência, ora com o monopólio, ora com manter ou elevar a venda de álbuns por meio de a perda de parte do controle sobre esses processos. experiência multimídia. O recurso, no entanto, Atualmente, com a internet e recursos para a seleção não garantiu estabilidade na comercialização do e execução de áudios de maneira gratuita em disposi- disco, que apresentou resultados inferiores aos tivos caracterizados, por vezes, por portabilidade, as trabalhos anteriores da artista - que não conta- gravadoras são desafiadas a pensar em soluções e es- vam com a plataforma para sua comercialização. tratégias para assegurar a estabilidade ou o aumento Tais implicações sugerem que o investimento das vendas de álbuns. Dentre os recursos desenvolvi- em uma nova plataforma não assegurou consis- dos com essa finalidade está o aplicativo para celular, tência de vendas para ‘Artpop’, com a influência que permite aos consumidores a imersão nas histórias de outros fatores, além do suporte material para propostas para os discos e, recentemente, a possibili- aquisição e execução das músicas, no sucesso do dade de aquisição dos mesmos, por meio da utilização projeto.