The Surprise Drop: the Cloverfield Paradox, Unreal, and Evolving Patterns in Streaming Media Distribution and Reception

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sep-Oct 2019

GOGRAND #alwaysentertaining SOCIALISE TALK MOVIES CL @GCLEBANON BOOK E/TICKET • E/KIOSK • GC MOBILE APP EXPERIENCE FIRSTWORD FEAT. DOLBY ATMOS ISSUE 125 When it’s time to GRAND MAGAZINE online edition kick back and relax now interactive! With school back in session, it’s easy to get caught up in preparations and never-ending homework — that’s why it’s important to unwind LOCATIONS and recharge with a dose of entertainment. And at Grand Cinemas, you can count on it. Stay tuned to our social media pages to find out LEBANON JORDAN about upcoming events, and take advantage of the G-POINTS Loyalty GRAND CINEMAS GRAND CINEMAS Card to access special offers and earn fantastic rewards. This issue in ABC VERDUN CITY MALL 01 795 697 962 65 813 461 GRAND MOMENTS, find out about the spectacular premiere attended MX4D featuring IMAX DOLBY ATMOS by French movie star Josephine Japy, among many other surprises. GRAND CLASS In our SPOTLIGHT feature, we talk to Johnny Depp about his CLUB SEATS KUWAIT GRAND AL HAMRA comedy drama Richard Says Goodbye, while 5 HOT FACTS rounds up GRAND CINEMAS LUXURY CENTER , ABC ACHRAFIEH 965 222 70 334 the most exciting tidbits about Domino starring Nikolaj Coster-Waldau. 01 209 109 MX4D ATMOS With FAMILY FIESTA you’re all set for the perfect outing: discover 70 415 200 GRAND GATE seven amazing stats about Shaun the Sheep: Farmageddon, get ready GRAND CINEMAS MALL ABC DBAYEH 965 220 56 464 to party with Big Sean and Snoop Dogg in Trouble, and check out 04 444 650 Angelina Jolie’s comeback in Maleficent: Mistress of Evil. -

Heather Mcintosh

HEATHER MCINTOSH COMPOSER FILM & VIDEO THE ART OF SELF-DEFENSE Andrew Kortschak, Walter Kortschak, Cody Ryder, End Cue Stephanie Whonsetler, prods. Riley Stearns, dir. WHAT IS DEMOCRACY Lea Marin, prod. National Film Board of Canada Astra Taylor, dir. HAL Jonathan Lynch, Brian Morrow, Christine Beebe, prods. Amy Scott, dir. 6 BALLOONS Channing Tatum, Samantha Housman, Peter Kiernan, Campfire Ross M. Dinerstein, Reid Carolin, prods. Marja Lewis Ryan, dir. WONDER VALLEY Rhianon Jones, prod. Wandering Vapor, LLC Heidi Hartwig, dir. LITTLE BITCHES Scott Aversano, Dan Carrillo Levy, Dom Genest, prods. Aversano Films Nick Kreiss, dir. TAKE ME Mark Duplass, Jay Duplass, Sev Ohanian, prods. Kidnap Solutions, LLC The Duplass Brothers, dir. AARDVARK Neal Dodson, Susan Leber, Zachary Quinto, prods. Great Point Media Brian Shoaf, dir. LIVING ROOM COFFIN Ian Michaels, Michael Sarrow, Sarah Smick, prods. Green Step Productions Michael Sarrow, dir. VALLEY OF THE MOON Harris Fishman, Patrick Mapel, prods. Patrick Mapel, dir. RADICAL GRACE Nicole Bernardi-Reis, Rebecca Parrish, prods. (documentary) Rebecca Parrish, dir. RAINBOW TIME Ian Michaels, Linas Phillips, prods. Duplass Brothers Productions Linas Phillips, dir. Z FOR ZACHARIAH Sophia Lin, Tobey Maguire, Skuli Fr. Malmquist, Lionsgate Matthew Plouffe, prods. Craig Zobel, dir. MANSON FAMILY VACATION Steve Bannatyne, Eric Blyler, J. Davis, J.M. Logan, prods. Lagolite Entertainment J. Davis, dir. The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. 818-260-8500 1 HEATHER MCINTOSH FAULTS Keith Calder, Mary Elizabeth Winstead, Snoot Entertainment Jessica Wu, prods. Riley Stearns, dir. GASP Adam Laupus, prod. Annika Kurnick, dir. THE WHITE CITY Moti Adiv, Gil Kofman, prods. Tanner King Barklow, Gil Kofman, dirs. HONEYMOON Patrick Baker, prod. -

Cold War II: Hollywood's Renewed Obsession with Russia

H-USA Edited Collection: Cold War II: Hollywood’s Renewed Obsession with Russia Discussion published by Tatiana Konrad on Monday, August 13, 2018 Date: October 1, 2018 The Cold War, with its bald confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union, has been widely depicted in film. Starting even before the conflict actually began with Ernst Lubitsch’s portrayals of communism in Ninotschka (1939), and ranging from Stanley Kubrick’s openly “Cold War” Dr. Strangelove (1963) to Fred Schepisi’s The Russia House (1990), Hollywood’s obsession with the Cold War, the Soviets/Russians, communism, and the political and ideological differences between the U.S. and Russia were pronounced. This obsession has persisted even after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the breakup of the Soviet Union. Cold War tropes continue to be (ab)used, as can be seen in multiple representations of evil Russians on screen, including Wolfgang Petersen’s Air Force One (1997), Jon Favreau’s Iron Man 2 (2010), Phillip Noyce’s Salt (2010), Brad Bird’s Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol (2011), John Moore’s A Good Day to Die Hard (2013), and Antoine Fuqua’s The Equalizer (2014), to name just a few. All these films portray Russians in a rather similar manner: as members of the mafia or as plain criminals. Yet recently Hollywood cinema has made a striking turn regarding its portrayals of Russians, returning to the images of the Cold War. This turn and the films that resulted from it are what the collection proposes to examine. The sanctions imposed on Russia during the Ukrainian crisis in 2014 by several Western countries, including the United States, along with Trump’s admiration for Putin, Russian attempts to influence the 2016 American election, the fatal poisoning in the UK, etc., have led to a tense relationship between Russia and the Western world. -

COVID Chronicle by Karen Wilkin

Art September 2020 COVID chronicle by Karen Wilkin On artists in lockdown. ’ve been asking many artists—some with significant track records, some aspiring, some I students—about the effect of the changed world we’ve been living in since mid-March. The responses have been both negative and positive, sometimes at the same time. People complain of too much solitude or not enough, of the luxury of more studio time or the stress of distance from the workspace or—worst case—of having lost it. There’s the challenge of not having one’s usual materials and the freedom to improvise out of necessity, the lack of interruption and the frustration of losing direct contact with peers and colleagues, and more. The drastic alterations in our usual habits over the past months have had sometimes dramatic, sometimes subtle repercussions in everyone’s work. Painters in oil are using watercolor, drawing, or experimenting with collage; makers of large-scale paintings are doing small pictures on the kitchen table. Ophir Agassi, an inventive painter of ambiguous narratives, has been incising drawings in mud, outdoors, with his young daughters. People complain of too much solitude or not enough, of the luxury of more studio time or the stress of distance from the workspace or—worst case—of having lost it. Many of the artists I’ve informally polled have had long-anticipated, carefully planned exhibitions postponed or canceled. In partial compensation, a wealth of online exhibitions and special features has appeared since mid-March, despite the obvious shortcomings of seeing paintings and sculptures on screen instead of experiencing their true size, surface, color, and all the rest of it. -

Statistical Yearbook 2019

STATISTICAL YEARBOOK 2019 Welcome to the 2019 BFI Statistical Yearbook. Compiled by the Research and Statistics Unit, this Yearbook presents the most comprehensive picture of film in the UK and the performance of British films abroad during 2018. This publication is one of the ways the BFI delivers on its commitment to evidence-based policy for film. We hope you enjoy this Yearbook and find it useful. 3 The BFI is the lead organisation for film in the UK. Founded in 1933, it is a registered charity governed by Royal Charter. In 2011, it was given additional responsibilities, becoming a Government arm’s-length body and distributor of Lottery funds for film, widening its strategic focus. The BFI now combines a cultural, creative and industrial role. The role brings together activities including the BFI National Archive, distribution, cultural programming, publishing and festivals with Lottery investment for film production, distribution, education, audience development, and market intelligence and research. The BFI Board of Governors is chaired by Josh Berger. We want to ensure that there are no barriers to accessing our publications. If you, or someone you know, would like a large print version of this report, please contact: Research and Statistics Unit British Film Institute 21 Stephen Street London W1T 1LN Email: [email protected] T: +44 (0)20 7173 3248 www.bfi.org.uk/statistics The British Film Institute is registered in England as a charity, number 287780. Registered address: 21 Stephen Street London W1T 1LN 4 Contents Film at the cinema -

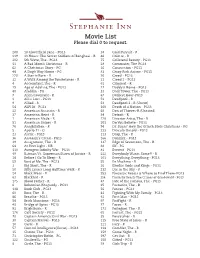

Movie List Please Dial 0 to Request

Movie List Please dial 0 to request. 200 10 Cloverfield Lane - PG13 38 Cold Pursuit - R 219 13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers of Benghazi - R 46 Colette - R 202 5th Wave, The - PG13 75 Collateral Beauty - PG13 11 A Bad Mom’s Christmas - R 28 Commuter, The-PG13 62 A Christmas Story - PG 16 Concussion - PG13 48 A Dog’s Way Home - PG 83 Crazy Rich Asians - PG13 220 A Star is Born - R 20 Creed - PG13 32 A Walk Among the Tombstones - R 21 Creed 2 - PG13 4 Accountant, The - R 61 Criminal - R 19 Age of Adaline, The - PG13 17 Daddy’s Home - PG13 40 Aladdin - PG 33 Dark Tower, The - PG13 7 Alien:Covenant - R 67 Darkest Hour-PG13 2 All is Lost - PG13 52 Deadpool - R 9 Allied - R 53 Deadpool 2 - R (Uncut) 54 ALPHA - PG13 160 Death of a Nation - PG13 22 American Assassin - R 68 Den of Thieves-R (Unrated) 37 American Heist - R 34 Detroit - R 1 American Made - R 128 Disaster Artist, The - R 51 American Sniper - R 201 Do You Believe - PG13 76 Annihilation - R 94 Dr. Suess’ How the Grinch Stole Christmas - PG 5 Apollo 11 - G 233 Dracula Untold - PG13 23 Arctic - PG13 113 Drop, The - R 36 Assassin’s Creed - PG13 166 Dunkirk - PG13 39 Assignment, The - R 137 Edge of Seventeen, The - R 64 At First Light - NR 88 Elf - PG 110 Avengers:Infinity War - PG13 81 Everest - PG13 49 Batman Vs. Superman:Dawn of Justice - R 222 Everybody Wants Some!! - R 18 Before I Go To Sleep - R 101 Everything, Everything - PG13 59 Best of Me, The - PG13 55 Ex Machina - R 3 Big Short, The - R 26 Exodus Gods and Kings - PG13 50 Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk - R 232 Eye In the Sky - -

Quentin Tarantino's KILL BILL: VOL

Presents QUENTIN TARANTINO’S DEATH PROOF Only at the Grindhouse Final Production Notes as of 5/15/07 International Press Contacts: PREMIER PR (CANNES FILM FESTIVAL) THE WEINSTEIN COMPANY Matthew Sanders / Emma Robinson Jill DiRaffaele Villa Ste Hélène 5700 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 600 45, Bd d’Alsace Los Angeles, CA 90036 06400 Cannes Tel: 323 207 3092 Tel: +33 493 99 03 02 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] From the longtime collaborators (FROM DUSK TILL DAWN, FOUR ROOMS, SIN CITY), two of the most renowned filmmakers this summer present two original, complete grindhouse films packed to the gills with guns and guts. Quentin Tarantino’s DEATH PROOF is a white knuckle ride behind the wheel of a psycho serial killer’s roving, revving, racing death machine. Robert Rodriguez’s PLANET TERROR is a heart-pounding trip to a town ravaged by a mysterious plague. Inspired by the unique distribution of independent horror classics of the sixties and seventies, these are two shockingly bold features replete with missing reels and plenty of exploitative mayhem. The impetus for grindhouse films began in the US during a time before the multiplex and state-of- the-art home theaters ruled the movie-going experience. The origins of the term “Grindhouse” are fuzzy: some cite the types of films shown (as in “Bump-and-Grind”) in run down former movie palaces; others point to a method of presentation -- movies were “grinded out” in ancient projectors one after another. Frequently, the movies were grouped by exploitation subgenre. Splatter, slasher, sexploitation, blaxploitation, cannibal and mondo movies would be grouped together and shown with graphic trailers. -

The BG News September 15, 2016

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 9-15-2016 The BG News September 15, 2016 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation State University, Bowling Green, "The BG News September 15, 2016" (2016). BG News (Student Newspaper). 8931. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/8931 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. An independent student press serving the campus and surrounding community, ESTABLISHED 1920 Bowling Green State University Thursday, September 15, 2016 | Volume 96, Issue 9 HOME FIELD The Falcon football team will return to the Doyt for Family Weekend to face Middle Tennessee. | PAGE 8 Predictions Native New health for the 68th American team insurance raises Primetime names are still concerns for Emmy Awards problematic students PAGE 11 PAGE 5 PAGE 7 AY ZIGGY! 2016 FALCON FOOTBALL GET YOUR ORANGE ON BGSU VS. MIDDLE TENNESSEE SATURDAY, SEPT. 17, NOON | FAMILY WEEKEND BGSUFALCONS.COM/STUDENT TICKETS BG NEWS September 15, 2016 | PAGE 12 Solar project to power 3,000 households By Kevin Bean Green’s energy portfolio. As the portfolio “The panels in our solar farm will provide energy to the city in an efficient Reporter stands now, approximately 36 percent of actually move as the sun moves across manner. -

MICHAEL BONVILLAIN, ASC Director of Photography

MICHAEL BONVILLAIN, ASC Director of Photography official website FEATURES (partial list) OUTSIDE THE WIRE Netflix Dir: Mikael Håfström AMERICAN ULTRA Lionsgate Dir: Nima Nourizadeh Trailer MARVEL ONE-SHOT: ALL HAIL THE KING Marvel Entertainment Dir: Drew Pearce ONE NIGHT SURPRISE Cathay Audiovisual Global Dir: Eva Jin HANSEL & GRETEL: WITCH HUNTERS Paramount Pictures Dir: Tommy Wirkola Trailer WANDERLUST Universal Pictures Dir: David Wain ZOMBIELAND Columbia Pictures Dir: Ruben Fleischer Trailer CLOVERFIELD Paramount Pictures Dir: Matt Reeves A TEXAS FUNERAL New City Releasing Dir: W. Blake Herron THE LAST MARSHAL Filmtown Entertainment Dir: Mike Kirton FROM DUSK TILL DAWN 3 Dimension Films Dir: P.J. Pesce AMONGST FRIENDS Fine Line Features Dir: Rob Weiss TELEVISION (partial list) PEACEMAKER (Season 1) HBO Max DIR: James Gunn WAYS & MEANS (Season 1) CBS EP: Mike Murphy, Ed Redlich HAP AND LEONARD (Season 3) Sundance TV, Netflix EP: Jim Mickle, Nick Damici, Jeremy Platt Trailer WESTWORLD (Utah; Season 1, 4 Episodes.) Bad Robot, HBO EP: Lisa Joy, Jonathan Nolan CHANCE (Pilot) Fox 21, Hulu EP: Michael London, Kem Nunn, Brian Grazer Trailer THE SHANNARA CHRONICLES MTV EP: Al Gough, Miles Millar, Jon Favreau (Pilot & Episode 102) FROM DUSK TIL DAWN (Season 1) Entertainment One EP: Juan Carlos Coto, Robert Rodriguez COMPANY TOWN (Pilot) CBS EP: Taylor Hackford, Bill Haber, Sera Gamble DIR: Taylor Hackford REVOLUTION (Pilot) NBC EP: Jon Favreau, Eric Kripke, Bryan Burk, J.J. Abrams DIR: Jon Favreau UNDERCOVERS (Pilot) NBC EP: J.J. Abrams, Bryan Burk, Josh Reims DIR: J.J. Abrams OUTLAW (Pilot) NBC EP: Richard Schwartz, Amanda Green, Lukas Reiter DIR: Terry George *FRINGE (Pilot) Fox Dir: J.J. -

Treball De Fi De Grau Títol

Facultat de Ciències de la Comunicació Treball de fi de grau Títol Autor/a Tutor/a Departament Grau Tipus de TFG Data Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Facultat de Ciències de la Comunicació Full resum del TFG Títol del Treball Fi de Grau: Català: Castellà: Anglès: Autor/a: Tutor/a: Curs: Grau: Paraules clau (mínim 3) Català: Castellà: Anglès: Resum del Treball Fi de Grau (extensió màxima 100 paraules) Català: Castellà: Anglès: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Índice 1. INTRODUCCIÓN ...................................................................................................... 2 Motivación personal: ............................................................................................. 2 2. MARCO TEÓRICO ................................................................................................... 3 2.1 BAD ROBOT ....................................................................................................... 3 2.2 JEFFREY JACOB ABRAMS ............................................................................... 5 2.3 BAD ROBOT: PRODUCCIONES CINEMATOGRÁFICAS Y SELLO PROPIO .... 7 3. METODOLOGÍA ..................................................................................................... 10 4. INVESTIGACIÓN DE CAMPO ................................................................................ 13 4.1 UNA NARRATIVA AUDIOVISUAL ÚNICA ........................................................ 13 4.1.1 PARTÍCULAS NARRATIVAS ......................................................................... 13 4.1.1.1 -

Umphrey's Mcgee It's You

Umphrey’s McGee it’s you Bio The music of Umphrey’s McGee unfolds like an unpredictable conversation between longtime friends. Its six participants—Brendan Bayliss [guitar, vocals], Jake Cinninger [guitar, vocals], Joel Cummins [keyboards, piano, vocals], Andy Farag [percussion], Kris Myers [drums, vocals], and Ryan Stasik [bass]—know just how to communicate with each other on stage and in the studio. A call of progressive guitar wizardry might elicit a response of soft acoustic balladry, or a funk groove could be answered by explosive percussion. At any moment, heavy guitars can give way to heavier blues as the boys uncover the elusive nexus between jaw-dropping instrumental virtuosity and airtight song craft. The conversation continues on their eleventh full-length album, it’s not us [Nothing Too Fancy Music]—which was released January 12, 2018. “It represents the band, because it basically runs the gamut from prog rock to dance,” says Brendan. “We’ve mastered our ADD here. The record really shows that.” “No matter what you’re into, there’s something on it’s not us that should speak to you,” agrees Joel. “This is a statement album for Umphrey’s McGee. The sound is as fresh as ever. The songs are strong as they’ve ever been. We’re always pushing forward.” It’s also how the band is celebrating its 20-year anniversary. Instead of retreading the catalog, they turn up with a pile of new tunes. “It’d be easy to play the hits from our first five or ten years,” continues Joel. “We’ve never been a band to rest on our laurels though. -

Taylor Swift New Album Target Code Digital Download Taylor Swift Says She Will Release Surprise Album at Midnight

taylor swift new album target code digital download Taylor Swift says she will release surprise album at midnight. Taylor Swift surprised fans Thursday morning by announcing that she would release her eighth studio album at midnight. Swift's new album, "Folklore," will be available to stream and purchase on Friday. In a series of tweets, Swift described the new record as one in which she's "poured all of my whims, dreams, fears, and musings into." Swift said that while the album was recorded entirely in isolation, she was still able to collaborate with several other musical artists, including Bon Iver, Jack Antonoff and Aaron Desner. Swift added that the standard album would include 16 songs, and the "deluxe" version will include one bonus track. Surprise Tonight at midnight I’ll be releasing my 8th studio album, folklore; an entire brand new album of songs I’ve poured all of my whims, dreams, fears, and musings into. Pre-order at https://t.co/zSHpnhUlLb pic.twitter.com/4ZVGy4l23b — Taylor Swift (@taylorswift13) July 23, 2020. She also announced she would release a music video on Thursday night for the song "Cardigan." "Folklore" will mark Swift's first full album release since last year, when she released her album "Lover." Digital Downloads. To access your files on an iOS device, you’ll need to first download to a desktop computer and then transfer the files to your device. Unfortunately, iOS devices don’t allow you to download music files directly to your phone. We apologize for the inconvenience! How to access your files on your Android Phone: To access the album on your phone, follow the link provided and click "Download" You will then be taken to the downloaded folder and you will then need to click "extract all" Once the album is finished downloading, a new folder will pop up to confirm that the files are in MP3 format You can then listen to the album on your phone's music app.