Part 1 Vision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Their Hats, Horses, and Homes, We Shall Know Them Opening June 18

The Magazine of History Colorado May/June 2016 By Their Hats, Horses, and Homes, We Shall Know Them Opening June 18 ALSO IN THIS ISSUE n Awkward Family Photos n A Guide to Our Community Museums n The National Historic Preservation Act at 50 n Spring and Summer Programs Around the State Colorado Heritage The Magazine of History Colorado History Colorado Center Steve Grinstead Managing Editor 1200 Broadway Liz Simmons Editorial Assistance Denver, Colorado 80203 303/HISTORY Darren Eurich, State of Colorado/IDS Graphic Designer Melissa VanOtterloo and Aaron Marcus Photographic Services Administration Public Relations 303/866-3355 303/866-3670 Colorado Heritage (ISSN 0272-9377), published by History Colorado, contains articles of broad general and educational Membership Group Sales Reservations interest that link the present to the past. Heritage is distributed 303/866-3639 303/866-2394 bimonthly to History Colorado members, to libraries, and to Museum Rentals Archaeology & institutions of higher learning. Manuscripts must be documented 303/866-4597 Historic Preservation when submitted, and originals are retained in the Publications 303/866-3392 office. An Author’s Guide is available; contact the Publications Research Librarians office. History Colorado disclaims responsibility for statements of 303/866-2305 State Historical Fund fact or of opinion made by contributors. 303/866-2825 Education 303/866-4686 Support Us Postage paid at Denver, Colorado 303/866-4737 All History Colorado members receive Colorado Heritage as a benefit of membership. Individual subscriptions are available For details about membership visit HistoryColorado.org and click through the Membership office for $40 per year (six issues). -

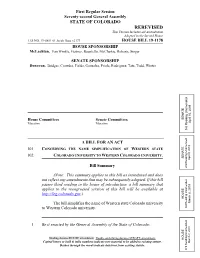

REREVISED This Version Includes All Amendments Adopted in the Second House LLS NO

First Regular Session Seventy-second General Assembly STATE OF COLORADO REREVISED This Version Includes All Amendments Adopted in the Second House LLS NO. 19-0851.01 Jacob Baus x2173 HOUSE BILL 19-1178 HOUSE SPONSORSHIP McLachlan, Van Winkle, Geitner, Buentello, McCluskie, Roberts, Singer SENATE SPONSORSHIP Donovan, Bridges, Crowder, Fields, Gonzales, Priola, Rodriguez, Tate, Todd, Winter House Committees Senate Committees SENATE Education Education April 10, 2019 3rd Reading Unamended 3rd Reading A BILL FOR AN ACT 101 CONCERNING THE NAME SIMPLIFICATION OF WESTERN STATE 102 COLORADO UNIVERSITY TO WESTERN COLORADO UNIVERSITY. SENATE April 9, 2019 Bill Summary 2nd Reading Unamended (Note: This summary applies to this bill as introduced and does not reflect any amendments that may be subsequently adopted. If this bill passes third reading in the house of introduction, a bill summary that applies to the reengrossed version of this bill will be available at http://leg.colorado.gov.) HOUSE The bill simplifies the name of Western state Colorado university March 8, 2019 to Western Colorado university. 3rd Reading Unamended 1 Be it enacted by the General Assembly of the State of Colorado: Shading denotes HOUSE amendment. Double underlining denotes SENATE amendment. HOUSE Capital letters or bold & italic numbers indicate new material to be added to existing statute. March 7, 2019 Dashes through the words indicate deletions from existing statute. 2nd Reading Unamended 1 SECTION 1. In Colorado Revised Statutes, amend 23-56-101 as 2 follows: 3 23-56-101. University established - role and mission. There is 4 hereby established a university at Gunnison, which shall be IS known as 5 Western state Colorado university. -

Colorado Local History: a Directory

r .DOCOMENt RESUME ED 114 318 SO 008 689. - 'AUTHOR Joy, Caro). M.,Comp.; Moqd, Terry Ann; Comp. .Colorado Lo41 History: A Directory.° INSTITUTION Colorado Library Association, Denver. SPONS AGENCY NColorado Centennial - Bicentennial Commission, I Benver. PUB DATE 75 NOTEAVAILABLE 131" 1? FROM Ezecuti p Secretary, Colorado Library Association, 4 1151 Co tilla Avenue, littletOn, Colorado 80122 ($3.00 paperbound) t, EDRS PR/CE MF-$0.76 Plus Postage. Not Available from EDRS. DESCPIPTORS. Community Characteristics: Community Study; Directories; Historiography; *Information Sources; Libraries; *Local HistOry;NLocal Issues; Museums; *Primary Sources; ReSearch Tools; *Resource Centers; *Social RistOry; 'Unitbd States History - IpDENTIFIPRS *Colorado;. Oral History ABSTPACT This directory lists by county 135 collections of local history.to be found in libraries, museums, histoc4,01 societies, schools, colleges,gand priVate collections in Colorado. The -directory includes only collections available in ColoradO Which, contain bibliographic holdings such as books, newspaper files or 4 clippings, letters, manuscripts, businessrecords, photoge*chs, and oral. history. Each-entry litts county, city, institution and address,, subject areas covered by the collection; formfi of material included, size of .collection, use policy, and operating hours. The materials. are.indexed by subject' and form far easy refetence. (DE) 9 A ******* *****************t***********.*********************************** Documents acquired by EtIC'include.many inforthal unpublished *- * materials. not available from other sources. ERIC makes every effort *- * to obtain the bett copy available., Nevertheless, items of marginal * - * reprodlicibility are often(' encountered and this affects tye,qual),ty..* * of the.microfiche'and hardcopy reproductions ERIC makes availibke * * via the ERIC Document Reproduction Service (EDRS). EDRS is not * .responsible for the quality. -

A Historic Buildings Survey of Old Fort Lewis Hesperus, Colorado 2007

A Historic Buildings Survey of Old Fort Lewis Hesperus, Colorado 2007 State Historical Fund Project Number 2007-02-019 Deliverable No. 7 Prepared for the Fort Lewis College Office of Community Services Cultural Resource Planning Historic Buildings Survey Old Fort Lewis, Hesperus, Colorado 2007 Prepared for: Office of Community Services Fort Lewis College Durango, Colorado 81301 (970) 247-7333 As part of the Cultural Resource Survey and Preservation Plan Project Number 2007-02-019 Deliverable Number 7 Prepared by: Jill Seyfarth Cultural Resource Planning PO Box 295 Durango, Colorado 81302 (970) 247-5893 October, 2007 Cover photograph from Fort Lewis College Center of Southwest Studies Fort Lewis Archives Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 Purpose Funding Source Project Summary Project Area .................................................................................................................. 2 General Area Description and Survey Area Boundaries Legal Description Research Design and Methods ...................................................................................... 5 Objectives File Search Survey Methods Historic Context ............................................................................................................ 7 Applicable Contexts Historic Development of Old Fort Lewis Survey Results ............................................................................................................ -

Colorado State University-Pueblo Adjunct Faculty Guide

Colorado State University-Pueblo Adjunct Faculty Guide Page 1 Adjunct Faculty Guide Table of Contents Introduction and Use of the Guide ..............................................4 Part I: The University ..................................................................4 History.............................................................................................4 Mission...........................................................................................4 Goal and Priorities..........................................................................5 Governance....................................................................................5 Accreditation ...................................................................................5 Affirmative Action/EOC....................................................................6 The Campus....................................................................................6 Campus Maps and Parking............................................................7 Campus Security.............................................................................7 List of University Official..................................................................7 University Calendar........................................................................7 CSU–Pueblo Bookstore ..................................................................8 Extended Studies………..................................................................8 Keys and Building Hours.................................................................8 -

In State College Essay and Payment Information COLLEGE ESSAY REQUIREMENT Payment Required Adams State University No Essay Compon

In State College Essay and Payment Information COLLEGE ESSAY REQUIREMENT Payment Required Adams State University No essay component $30 Application Colorado School of Mines No essay component unless requested after application $45 Application Colorado State University Community Service and Leadership $50 Application Payment is required to submit the online application for admission; electronic check, Visa Highlight the school, family and community activities that best and MasterCard options are available. Fee illustrate your skills, commitment and achievements. Help us waivers are granted on a case-by-case basis in see what has been meaningful to you and how Colorado State the presence of documented financial hardship. University can help you reach that next step. The fee waiver request is built into the application for admission. Ability to Contribute to a Diverse Campus Community The University has a compelling interest in promoting a diverse student body because of the educational benefits that flow from such diversity. Diversity can include but is not limited to age, gender, race/ethnicity, first-generation status, disability (physical or learning), sexual orientation, geographic origin (e.g. nonresident, rural, international background), personal background (e.g. homeschooled, recognition of special talent), or pursuit of a unique or underrepresented major. Unique and/or Compelling Circumstances Tell us about experiences you have had that have set you apart from your peers, that have impacted you, that have helped you set personal -

Illegal Fencing on the Colorado Range

Illegal Fencing on the Colorado Range BY WILLIAM R. WHITE The end of the Civil War witnessed a boom in the cattle business in the western states. Because of the depletion of eastern herds during the war, a demand for cheap Texas beef in creased steadily during the late eighteen-sixties and the early eighteen-seventies. This beef also was in demand by those in dividuals who planned to take advantage of the free grass on the Great Plains, which had remained untouched prior to the war, except by the buffalo. Each year thousands of Texas cattle were driven north to stock the various ranges claimed by numerous cattlemen or would-be cattlemen. The usual practice of an aspir ing cattleman was to register a homestead claim along some stream where the ranch house and outbuildings were con structed. His cattle then were grazed chiefly upon the public lands where they "were merely on sufferance and not by right of any grant or permission from the government. " 1 The Homestead, Preemption, Timber Culture, and Desert Land acts had been enacted to enable persons to secure government land easily, but "the amount of acreage allowed was not even remotely enough to meet the needs of the western stockgrowers. " 2 Although the government land laws were not designed for cattlemen, they made extensive use of them. The statutes served the cattlemen, however, only as the cattlemen violated the spirit of the law. 3 During the sixties and the seventies cattlemen tended to respect the range claims of their neighbors and "the custom of priority-the idea of squatter sovereignty met the 1 Clifford P. -

An, Fischer, Hamner, Kagan, Kerr J., Labuda, Massey, Pabon, Pace, Schafer S., Todd; Also SENATOR(S) Schwartz, Bacon, Giron, Guzman, Heath, Johnston, King S

Ch. 189 Education - Postsecondary 753 CHAPTER 189 _______________ EDUCATION - POSTSECONDARY _______________ HOUSE BILL 12-1080 BY REPRESENTATIVE(S) Vigil, Duran, Fischer, Hamner, Kagan, Kerr J., Labuda, Massey, Pabon, Pace, Schafer S., Todd; also SENATOR(S) Schwartz, Bacon, Giron, Guzman, Heath, Johnston, King S. AN ACT CONCERNING CHANGING THE NAM E OF ADAM S STATE COLLEGE TO ADAM S STATE UNIVERSITY. Be it enacted by the General Assembly of the State of Colorado: SECTION 1. In Colorado Revised Statutes, amend 23-51-101 as follows: 23-51-101. University established - role and mission. There is hereby established a college at Alamosa, to be known as Adams state college UNIVERSITY, which shall be a general baccalaureate institution with moderately selective admission standards. Adams state college UNIVERSITY shall offer undergraduate liberal arts and sciences, teacher preparation, and business degree programs, a limited number of master's GRADUATE level programs, and two-year transfer programs with a community college role and mission. Adams state college shall not offer vocational education programs. Adams state college UNIVERSITY shall receive resident credit for two-year course offerings in its commission-approved service area. Adams state college UNIVERSITY has a significant responsibility to provide access to teacher education in rural Colorado. Adams state college UNIVERSITY shall also serve as a regional education provider. In addition, Adams state college UNIVERSITY shall offer programs, when feasible, that preserve and promote the unique history and culture of the region. SECTION 2. In Colorado Revised Statutes, 23-51-102, amend (1), (3), (4), (6), and (7) as follows: 23-51-102. Board of trustees - creation - members - powers - duties. -

Pioneers, Prospectors and Trout a Historic Context for La Plata County, Colorado

Pioneers, Prospectors and Trout A Historic Context For La Plata County, Colorado By Jill Seyfarth And Ruth Lambert, Ph.D. January, 2010 Pioneers, Prospectors and Trout A Historic Context For La Plata County, Colorado Prepared for the La Plata County Planning Department State Historical Fund Project Number 2008-01-012 Deliverable No. 7 Prepared by: Jill Seyfarth Cultural Resource Planning PO Box 295 Durango, Colorado 81302 (970) 247-5893 And Ruth Lambert, PhD. San Juan Mountains Association PO Box 2261 Durango, Colorado 81302 January, 2010 This context document is sponsored by La Plata County and is partially funded by a grant from the Colorado State Historical Fund (Project Number 2008-01-012). The opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of the staff of the Colorado State Historical Fund. Cover photographs: Top-Pine River Stage Station. Photo Source: La Plata County Historical Society-Animas Museum Photo Archives. Left side-Gold King Mill in La Plata Canyon taken in about1936. Photo Source Plate 21, in U.S.Geological Survey Professional paper 219. 1949 Right side-Local Fred Klatt’s big catch. Photo Source La Plata County Historical Society- Animas Museum Photo Archives. Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 New Frontiers................................................................................................................ 3 Initial Exploration ............................................................................................ -

San Juan Public Lands People Employee News San Juan National Forest San Juan Field Office-BLM Fall 2005

SOUTHWEST PUBLIC LANDS PEOPLE 1 San Juan Public Lands People Employee News San Juan National Forest San Juan Field Office-BLM Fall 2005 San Juan Employees Help Pets Rescued from Flood Waters By Ann Bond DURANGO - It’s not every day a huge charter jet lands at the La Plata County Airport, and still more unusual when the passengers are all canine and feline. About 80 dogs and a handful of cats arrived in Durango this fall from Louisiana animal shel- ters, where they had been housed since being Photo by Ann Bond rescued from floodwaters in New Orleans. Some 40 volunteers with the La Plata and SJNF employee Becca Smith of Pagosa Pagosa Springs Humane Societies and Dogster’s Springs unloads a weary traveler. Spay and Neuter Program (DSNiP) greeted the weary travelers with water, treats, new collars and leashes, medical care, and best yet, foster homes. Dogs ranged from Chihuahuas to rottweilers, poodles to pit bulls, and puppies to senior canine citizens. One by one, each was escorted by a volunteer handler through stations where veterinarians donated medical services, including microchipping, physical check- ups, worming, heartworm tests, and inoculation. Volunteers photographed the animals and loaded pertinent information onto computers for posting on the Petfinders Web site, where, hopefully, their owners will be able to locate them. Pets that needed a little sprucing up were bathed onsite. Photo by Ann Bond Foster families from Pagosa Springs to Telluride whisked the creatures off to the com- forts of home, as soon as medical care and identification procedures were complete. SJNF employee Laurie Robison of Bayfield readies a dog for (Ann Bond is San Juan Public Lands Public Affairs Specialist and a volunteer with DSNiP.) medical attention. -

2006-2007 Final Press Release

Rocky Mountain Athletic Conference 1867 Austin Bluff s Parkway --- Suite 101 --- Colorado Springs, Colo. 80918 Contact: Sarah Meier (719) 471-4936 or [email protected] Contact: Anne Manning (719) 471-0066 or [email protected] www.rmacsports.org 2006-07 RMAC Go lf Final Relea se Ma y 31, 2007 Results from NCAA Men’ s DII Champ ionships Re sults f rom NCAA Wom en’s We st Reg ional T he Mea dows Pa r 71 - 6992 yards The Go lf Club at Circ le C Grand Valley S tate Uni versity A ustin, Te xas TEAM RESULTS TEAM RESULTS 1 2 3 4 Total Pl. School 1 2 3 Total 1 Barry University 289 297 304 296 1186 1 Tarleton State 307 308 308 923 2 S. Carolina Upstate 296 297 305 289 1187 2 Northeastern State 308 313 306 927 3 Florida Southern Col 299 292 305 292 1188 3 St. Edward’s University 311 313 306 930 4 Columbus State U. 302 291 299 297 1189 4 Western Washington U 313 309 324 946 5 Washburn University 296 306 298 296 1196 5 Central Oklahoma 319 307 325 951 T6 Georgia Coll & St. U 304 297 302 298 1201 6 Western New Mexico 323 320 310 953 T6 Belmont Abbey Coll. 302 306 300 293 1201 T8 Abilene Christian U. 306 301 299 296 1202 WESTERN NEW MEXICO INDIVIDUAL RESULTS T8 CSU-Stanislaus 307 296 303 296 1202 Pl. School 1 2 3 Total 10 Grand Canyon U. 292 305 315 295 1207 T19 Tina Bickford 77 84 75 236 11 CSU-San Bernardino 300 306 311 296 1213 T25 Heather Dorris 83 80 78 241 12 North Alabama, U. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Megan Mcdermott, Director of Communications Office: 303-974-2495, Mobile: 720-394-3205, [email protected]

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Megan McDermott, Director of Communications Office: 303-974-2495, Mobile: 720-394-3205, [email protected] Colorado Opportunity Scholarship Initiative approves 29 new local scholarship proposals DENVER, May 31, 2017 – The Colorado Opportunity Scholarship Initiative (COSI) board approved 29 local scholarship proposals worth $2.5 million to counties, institutions of higher education and workforce development organizations. One-to-one matches of community and state funds will grow the tuition support for student scholarships to a total of $5 million. “Thanks to the generosity of our partners, we’ve made more than 4,700 scholarships available for Colorado students,” said Dr. Kim Hunter Reed, executive director of the Colorado Department of Higher Education. “We’re eager to expand our success to more counties and public institutions as we focus on making higher education more accessible and affordable for every Coloradan.” This was the fourth and final COSI proposal review period for 2016-2017. A new round of funding will open again in August 2017, allowing applicants to apply for a portion of the $7.5 million in matching scholarship funds available in 2017-2018. “In addition to our larger counties and institutions, the team worked diligently with smaller communities to ensure all areas of the state planned to continue their participation,” said Shelley Banker, director of the Colorado Opportunity Scholarship Initiative. “The team provided a significant amount of technical assistance to encourage applications and participation to grow support for Colorado students.” The 29 awards represent 32 counties ($2,155,034), six institutions of higher education ($232,058) and three workforce programs ($113,000).