Illegal Fencing on the Colorado Range

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women, Old and Aware: Living As a Minority in Extended Care Institutions

WOMEN, OLD AND AWARE: LIVING AS A MINORITY IN EXTENDED CARE INSTITUTIONS by Linda-Mae Campbell B.A., The University of Alberta, 1982 B.S.W., The University of Victoria, 1990 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SOCIAL WORK in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 1998 © Linda-Mae Campbell, 1998 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. 0 Department The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada DE-6 (2/88) Abstract Women Old And Aware: Living As A Minority In Extended Care Institutions The purpose of this phenomenological study was to describe the everyday lived experiences of old, cognitively intact women, residing in an integrated extended care facility among an overwhelming majority of confused elderly people. The research question was "From your perspective, what is the impact of living in an environment where the majority of residents, with whom you reside, are cognitively impaired?". A purposive sample of five older women participated in multiple in-depth interviews about their subjective experiences. -

Corporate Impersonation: the Possibilities of Personhood in American Literature, 1886-1917

Corporate Impersonation: The Possibilities of Personhood in American Literature, 1886-1917 by Nicolette Isabel Bruner A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee Professor Gregg D. Crane, Chair Professor Susanna L. Blumenthal, University of Minnesota Professor Jonathan L. Freedman Associate Professor Scott R. Lyons “Everything…that the community chooses to regard as such can become a subject—a potential center—of rights, whether a plant or an animal, a human being or an imagined spirit; and nothing, if the community does not choose to regard it so, will become a subject of rights, whether human being or anything else.” -Alexander Nékám, 1938 © Nicolette Isabel Bruner Olson 2015 For my family – past, present, and future. ii Acknowledgements This dissertation could not have been completed without the support of my committee: Gregg Crane, Jonathan Freedman, Scott Lyons, and Susanna Blumenthal. Gregg Crane has been a constant source of advice and encouragement whose intimate knowledge of law and literature scholarship has been invaluable to my own development as a scholar. Jonathan Freedman’s class on “Fictions of Finance” inspired much of the work in this dissertation, as did Susanna Blumenthal’s seminar on “The Concept of the Person” during my time at the University of Michigan Law School. Jonathan’s good humor, grace, and sympathetic yet critical eye have profoundly shaped my work. As I have expanded my research into animal studies, Scott Lyons guided me to new intellectual domains. Finally, ever since I began working with her during my first year of law school, Susanna has been a source of wisdom, encouragement, and generosity. -

By Their Hats, Horses, and Homes, We Shall Know Them Opening June 18

The Magazine of History Colorado May/June 2016 By Their Hats, Horses, and Homes, We Shall Know Them Opening June 18 ALSO IN THIS ISSUE n Awkward Family Photos n A Guide to Our Community Museums n The National Historic Preservation Act at 50 n Spring and Summer Programs Around the State Colorado Heritage The Magazine of History Colorado History Colorado Center Steve Grinstead Managing Editor 1200 Broadway Liz Simmons Editorial Assistance Denver, Colorado 80203 303/HISTORY Darren Eurich, State of Colorado/IDS Graphic Designer Melissa VanOtterloo and Aaron Marcus Photographic Services Administration Public Relations 303/866-3355 303/866-3670 Colorado Heritage (ISSN 0272-9377), published by History Colorado, contains articles of broad general and educational Membership Group Sales Reservations interest that link the present to the past. Heritage is distributed 303/866-3639 303/866-2394 bimonthly to History Colorado members, to libraries, and to Museum Rentals Archaeology & institutions of higher learning. Manuscripts must be documented 303/866-4597 Historic Preservation when submitted, and originals are retained in the Publications 303/866-3392 office. An Author’s Guide is available; contact the Publications Research Librarians office. History Colorado disclaims responsibility for statements of 303/866-2305 State Historical Fund fact or of opinion made by contributors. 303/866-2825 Education 303/866-4686 Support Us Postage paid at Denver, Colorado 303/866-4737 All History Colorado members receive Colorado Heritage as a benefit of membership. Individual subscriptions are available For details about membership visit HistoryColorado.org and click through the Membership office for $40 per year (six issues). -

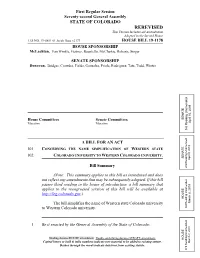

REREVISED This Version Includes All Amendments Adopted in the Second House LLS NO

First Regular Session Seventy-second General Assembly STATE OF COLORADO REREVISED This Version Includes All Amendments Adopted in the Second House LLS NO. 19-0851.01 Jacob Baus x2173 HOUSE BILL 19-1178 HOUSE SPONSORSHIP McLachlan, Van Winkle, Geitner, Buentello, McCluskie, Roberts, Singer SENATE SPONSORSHIP Donovan, Bridges, Crowder, Fields, Gonzales, Priola, Rodriguez, Tate, Todd, Winter House Committees Senate Committees SENATE Education Education April 10, 2019 3rd Reading Unamended 3rd Reading A BILL FOR AN ACT 101 CONCERNING THE NAME SIMPLIFICATION OF WESTERN STATE 102 COLORADO UNIVERSITY TO WESTERN COLORADO UNIVERSITY. SENATE April 9, 2019 Bill Summary 2nd Reading Unamended (Note: This summary applies to this bill as introduced and does not reflect any amendments that may be subsequently adopted. If this bill passes third reading in the house of introduction, a bill summary that applies to the reengrossed version of this bill will be available at http://leg.colorado.gov.) HOUSE The bill simplifies the name of Western state Colorado university March 8, 2019 to Western Colorado university. 3rd Reading Unamended 1 Be it enacted by the General Assembly of the State of Colorado: Shading denotes HOUSE amendment. Double underlining denotes SENATE amendment. HOUSE Capital letters or bold & italic numbers indicate new material to be added to existing statute. March 7, 2019 Dashes through the words indicate deletions from existing statute. 2nd Reading Unamended 1 SECTION 1. In Colorado Revised Statutes, amend 23-56-101 as 2 follows: 3 23-56-101. University established - role and mission. There is 4 hereby established a university at Gunnison, which shall be IS known as 5 Western state Colorado university. -

Update September 2018 Colorado/Cherokee Trail Chapter News and Events

Update September 2018 Colorado/Cherokee Trail Chapter News and Events Welcome New and Returning Members Bill and Sally Burr Jack and Jody Lawson Emerson and Pamela Shipe John and Susie Winner . Chapter Members Attending the 2018 Ogden, Utah Convention L-R: Gary and Ginny Dissette, Bruce and Peggy Watson, Camille Bradford, Kent Scribner, Jane Vander Brook, Chuck Hornbuckle, Lynn and Mark Voth. Photo by Roger Blair. Preserving the Historic Road Conference September 13-16 Preserving the Historic Road is the leading international conference dedicated to the identification, preservation and management of historic roads. The 2018 Conference will be held in historic downtown Fort Collins and will celebrate twenty years of advocacy for historic roads and look to the future of this important heritage movement that began in 1998 with the first conference in Los Angeles. The 2018 conference promises to be an exceptional venue for robust discussions and debates on the future of historic roads in the United States and around the globe. Don't miss important educational sessions showcasing how the preservation of historic roads contributes to the economic, transportation, recreational, and cultural needs of your community. The planning committee for Preserving the Historic Road 2018 has issued a formal Call for Papers for presentations at the September 13-16, 2018 conference. Interested professionals, academics and advocates are encouraged to submit paper abstracts for review and consideration by the planning committee. The planning committee is seeking paper abstracts that showcase a number of issues related to the historic road and road systems such as: future directions and approaches for the identification, preservation and management of historic roads to identify priorities for the next twenty years of research, advocacy and action. -

Colorado Southern Frontier Historic Context

607 COLORADO SOUTHERN FRONTIER HISTORIC CONTEXT PLAINS PLATEAU COUNTRY MOUNTAINS SOUTHERN FRONTIER OFFICE OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORIC PRESERVATION COLORADO HISTORICAL SOCIETY COLORADO SOUTHERN FRONTIER HISTORIC CONTEXT CARROL JOE CARTER STEVEN F. MEHLS © 1984 COLORADO HISTORICAL SOCIETY FACSIMILE EDITION 2006 OFFICE OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORIC PRESERVATION COLORADO HISTORICAL SOCIETY 1300 BROADWAY DENVER, CO 80203 The activity which is the subject of this material has been financed in part with Federal funds from the National Historic Preservation Act, administered by the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior and for the Colorado Historical Society. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Department of the Interior or the Society, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute an endorsement or recommendation by the Department of the Interior or the Society. This program receives Federal funds from the National Park Service. Regulations of the U.S. Department of the Interior strictly prohibit unlawful discrimination in departmental Federally assisted programs on the basis of race, color, national origin, age or handicap. Any person who believes he or she has been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility operated by a recipient of Federal assistance should write to: Director, Equal Opportunity Program, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1849 C Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20240. This is a facsimile edition of the original 1984 publication. Text and graphics are those of the original edition. CONTENTS SOUTHERN FRONTIER Page no. 1. Spanish Dominance (1664-1822) .• II-1 2. Trading �nd Trapping (1803-1880) . -

Colorado Local History: a Directory

r .DOCOMENt RESUME ED 114 318 SO 008 689. - 'AUTHOR Joy, Caro). M.,Comp.; Moqd, Terry Ann; Comp. .Colorado Lo41 History: A Directory.° INSTITUTION Colorado Library Association, Denver. SPONS AGENCY NColorado Centennial - Bicentennial Commission, I Benver. PUB DATE 75 NOTEAVAILABLE 131" 1? FROM Ezecuti p Secretary, Colorado Library Association, 4 1151 Co tilla Avenue, littletOn, Colorado 80122 ($3.00 paperbound) t, EDRS PR/CE MF-$0.76 Plus Postage. Not Available from EDRS. DESCPIPTORS. Community Characteristics: Community Study; Directories; Historiography; *Information Sources; Libraries; *Local HistOry;NLocal Issues; Museums; *Primary Sources; ReSearch Tools; *Resource Centers; *Social RistOry; 'Unitbd States History - IpDENTIFIPRS *Colorado;. Oral History ABSTPACT This directory lists by county 135 collections of local history.to be found in libraries, museums, histoc4,01 societies, schools, colleges,gand priVate collections in Colorado. The -directory includes only collections available in ColoradO Which, contain bibliographic holdings such as books, newspaper files or 4 clippings, letters, manuscripts, businessrecords, photoge*chs, and oral. history. Each-entry litts county, city, institution and address,, subject areas covered by the collection; formfi of material included, size of .collection, use policy, and operating hours. The materials. are.indexed by subject' and form far easy refetence. (DE) 9 A ******* *****************t***********.*********************************** Documents acquired by EtIC'include.many inforthal unpublished *- * materials. not available from other sources. ERIC makes every effort *- * to obtain the bett copy available., Nevertheless, items of marginal * - * reprodlicibility are often(' encountered and this affects tye,qual),ty..* * of the.microfiche'and hardcopy reproductions ERIC makes availibke * * via the ERIC Document Reproduction Service (EDRS). EDRS is not * .responsible for the quality. -

A Historic Buildings Survey of Old Fort Lewis Hesperus, Colorado 2007

A Historic Buildings Survey of Old Fort Lewis Hesperus, Colorado 2007 State Historical Fund Project Number 2007-02-019 Deliverable No. 7 Prepared for the Fort Lewis College Office of Community Services Cultural Resource Planning Historic Buildings Survey Old Fort Lewis, Hesperus, Colorado 2007 Prepared for: Office of Community Services Fort Lewis College Durango, Colorado 81301 (970) 247-7333 As part of the Cultural Resource Survey and Preservation Plan Project Number 2007-02-019 Deliverable Number 7 Prepared by: Jill Seyfarth Cultural Resource Planning PO Box 295 Durango, Colorado 81302 (970) 247-5893 October, 2007 Cover photograph from Fort Lewis College Center of Southwest Studies Fort Lewis Archives Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 Purpose Funding Source Project Summary Project Area .................................................................................................................. 2 General Area Description and Survey Area Boundaries Legal Description Research Design and Methods ...................................................................................... 5 Objectives File Search Survey Methods Historic Context ............................................................................................................ 7 Applicable Contexts Historic Development of Old Fort Lewis Survey Results ............................................................................................................ -

Colorado State University-Pueblo Adjunct Faculty Guide

Colorado State University-Pueblo Adjunct Faculty Guide Page 1 Adjunct Faculty Guide Table of Contents Introduction and Use of the Guide ..............................................4 Part I: The University ..................................................................4 History.............................................................................................4 Mission...........................................................................................4 Goal and Priorities..........................................................................5 Governance....................................................................................5 Accreditation ...................................................................................5 Affirmative Action/EOC....................................................................6 The Campus....................................................................................6 Campus Maps and Parking............................................................7 Campus Security.............................................................................7 List of University Official..................................................................7 University Calendar........................................................................7 CSU–Pueblo Bookstore ..................................................................8 Extended Studies………..................................................................8 Keys and Building Hours.................................................................8 -

The Overland Trail

OREGON-CALIFORNIA TRAILS ASSOCIATION 27TH ANNUAL CONVENTION August 18-22, 2009 Loveland, Colorado Hosted by Colorado-Cherokee Trail Chapter Convention Booklet Cherokee Trail to the West 1849 ·· 18SS OCTA 2009 Lovelana, Colorana Au�ust 18-2 2 Cherokee Trail to the West, 1849-1859 OREGON-CALIFORNIA TRAILS ASSOCIATION 27th ANNUAL CONVENTION August 18-22, 2009 Loveland, Colorado Hosted by Colorado-Cherokee Trail Chapter Compiled and Edited by Susan Badger Doyle with the assistance of Bob Clark, Susan Kniebes, and Bob Rummel Welcome to the 27th Annual OCTA Convention Loveland, Colorado About the Convention The official host motel, Best Western Crossroads Inn & Conference Center, is the site for the meeting of the OCTA Board of Directors on Tuesday, August 18. The remaining convention activities and the boarding and disembarking of convention tour buses will take place at TheRanch I., rimer Coumy F mgrounds and Fven ts Com pie 5280 Arena Circle, Loveland OCTA activities will be in the Thomas M. McKee 4-H, Youth, and Community Building on the south side of Arena Circle at The Ranch. Raffle and Live Auction There will be a live auction on August20. Our auctioneer is OCTA member John Winner. The annual rafflewill also be conducted throughout the week. BOOK ROOM/EXHIBIT ROOM HOURS REGISTRATION/INFORMATION DESK HOURS Aug 18 6:00 p.m.-9:00 p.m. Aug 18 9:00 a.m.-9:00 p.m. Aug 19 9:45 a.m.-6:00 p.m. Aug 19 7:00 a.m.-6:00 p.m. Aug 20 4:30 p.m.-6:30 p.m. -

In State College Essay and Payment Information COLLEGE ESSAY REQUIREMENT Payment Required Adams State University No Essay Compon

In State College Essay and Payment Information COLLEGE ESSAY REQUIREMENT Payment Required Adams State University No essay component $30 Application Colorado School of Mines No essay component unless requested after application $45 Application Colorado State University Community Service and Leadership $50 Application Payment is required to submit the online application for admission; electronic check, Visa Highlight the school, family and community activities that best and MasterCard options are available. Fee illustrate your skills, commitment and achievements. Help us waivers are granted on a case-by-case basis in see what has been meaningful to you and how Colorado State the presence of documented financial hardship. University can help you reach that next step. The fee waiver request is built into the application for admission. Ability to Contribute to a Diverse Campus Community The University has a compelling interest in promoting a diverse student body because of the educational benefits that flow from such diversity. Diversity can include but is not limited to age, gender, race/ethnicity, first-generation status, disability (physical or learning), sexual orientation, geographic origin (e.g. nonresident, rural, international background), personal background (e.g. homeschooled, recognition of special talent), or pursuit of a unique or underrepresented major. Unique and/or Compelling Circumstances Tell us about experiences you have had that have set you apart from your peers, that have impacted you, that have helped you set personal -

Wagon Tracks Volume 33, Issue 1 Article 1 (November 2018)

Wagon Tracks Volume 33 Issue 1 Wagon Tracks Volume 33, Issue 1 Article 1 (November 2018) 2019 Wagon Tracks Volume 33, Issue 1 (November 2018) Santa Fe Trail Association Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/wagon_tracks Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Santa Fe Trail Association. "Wagon Tracks Volume 33, Issue 1 (November 2018)." Wagon Tracks 33, 1 (2019). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/wagon_tracks/vol33/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wagon Tracks by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. : Wagon Tracks Volume 33, Issue 1 (November 2018) Quarterly Publication of the Santa Fe Trail Association volume 33 ♦ number 1 November 2018 Warfare and Death on the Santa Fe Trail ♦ page 10 Selections from Rendezvous Presentations ♦ page 16 Business Techniques in the Santa Fe Trade ♦ page 19 Published by UNM Digital Repository, 2019 Why the Cherokee Trail is Important ♦ page 22 1 Wagon Tracks, Vol. 33 [2019], Iss. 1, Art. 1 On the Cover: Pawnee Indians Watching a Caravan by Alfred Jacob Miller Courtesy: The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore art.thewalters.org “Of all the Indian tribes I think the Pawnee gave us the most trouble, and were (of all) to be most zealously guarded against. We knew that the Blackfeet were our deadly enemies, forwarned here was to be forearmed. Now the Pawnees pretended amity, and were a species of ‘confidence Men.’ They reminded us of two German students meeting for the first time, and one saying to the other, ‘Let’s you and I swear eternal friendship.’ In passing through their country, it was most desirable and indeed essential to cultivate their good will, but these fellow had le main croche.