Merchant of Venice SMART Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Merchant of Venice William Shakespeare Reviewed By: Kartikeya Krishna, 15 Star Teen Book Reviewer of Be the Star You Are! Charity

The Merchant of Venice William Shakespeare Reviewed by: Kartikeya Krishna, 15 Star Teen Book Reviewer of Be the Star You Are! Charity www.bethestaryouare.org Antonio is a young Venetian man and one of the most successful merchants of Venice, known for being kind and generous. His friend Bassanio wishes to travel to the city of Belmont to woo Portia, one of the most beautiful women in the world left with an amazing amount of money left after the death of her father. Bassanio asks Antonio if he can fund his trip to Belmont and Antonio, who is poor as of the moment as his ships are at sail, agrees as long as Bassanio can find a loaner, who turns out to be Shylock. Shylock hates Antonio because his racist attitude towards Jews, shown by Shylock being insulted and spat on by Antonio for being a Jew. Shylock decrees that if Antonio is unable to repay his loan before a specific date, he may take a pound of flesh from any part of Antonio’s body that he chooses. Antonio accepts the offer on account of being “surprised by Shylock’s generosity.” Bassanio leaves towards Belmont with his friend Gratanio. In Belmont, Portia’s father’s will is refraining her from marrying, stating that each of her suitors must choose correctly from one of three caskets -- gold, silver, and lead -- and if they choose correctly, they get Portia. If they are incorrect, they must leave and never marry. The first suitor chooses the gold casket because the casket says "Choose me and get what most men desire", which must be Portia, as what all men desire is Portia. -

![English 202 in Italy Text 2: [Official Course Title: English 280-1] Shakespeare, the Merchant of World Literature I Dr](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5082/english-202-in-italy-text-2-official-course-title-english-280-1-shakespeare-the-merchant-of-world-literature-i-dr-1175082.webp)

English 202 in Italy Text 2: [Official Course Title: English 280-1] Shakespeare, the Merchant of World Literature I Dr

Text 2: English 202 in Italy [Official course title: English 280-1] Shakespeare, The Merchant of World Literature I Venice Dr. Gavin Richardson EDITION: Any; the Folger Shakespeare is recommended. READING JOURNAL: In a separate document, write 3-5 thoughtful sentences in response to each of these reading journal prompts: 1. Act 1 scene 3 features the crucial loan scene. At this point, do you think Shylock is serious about the pound of flesh he demands as collateral for Antonio’s loan for Bassanio? Why or why not? 2. In 2.3. Jessica leaves her (Jewish) father for her (Christian) husband. Does her desertion create sympathy for Shylock? Or do we cheer her action? Is her “conversion” an uplifting one? 3. Shylock’s speech in 3.1.58–73 may be the most famous of the entire play. After reading this speech, review Ann Barton’s comments on the performing of Shylock and write a paragraph on what you think Shylock means to Shakespeare: “Shylock is a closely observed human being, not a bogeyman to frighten children in the nursery. In the theatre, the part has always attracted actors, and it has been played in a variety of ways. Shylock has sometimes been presented as the devil incarnate, sometimes as a comic villain gabbling absurdly about ducats and daughters. He has also been sentimentalized as a wronged and suffering father nobler by far than the people who triumph over him. Roughly the same range of interpretation can be found in criticism on the play. Shakespeare’s text suggests a truth more complex than any of these extremes.” 4. -

Revisiting Shakespeare's Problem Plays: the Merchant of Venice

Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of English Language and Literature REVISITING SHAKESPEARE’S PROBLEM PLAYS: THE MERCHANT OF VENICE, HAMLET AND MEASURE FOR MEASURE Emine Seda ÇAĞLAYAN MAZANOĞLU Ph.D. Dissertation Ankara, 2017 REVISITING SHAKESPEARE’S PROBLEM PLAYS: THE MERCHANT OF VENICE, HAMLET AND MEASURE FOR MEASURE Emine Seda ÇAĞLAYAN MAZANOĞLU Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of English Language and Literature Ph.D. Dissertation Ankara, 2017 v For Hayriye Gülden, Sertaç Süleyman and Talat Serhat ÇAĞLAYAN and Emre MAZANOĞLU vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to express my endless gratitude to my supervisor, Prof. Dr. A. Deniz BOZER for her great support, everlasting patience and invaluable guidance. Through her extensive knowledge and experience, she has been a model for me. She has been a source of inspiration for my future academic career and made it possible for me to recognise the things that I can achieve. I am extremely grateful to Prof. Dr. Himmet UMUNÇ, Prof. Dr. Burçin EROL, Asst. Prof. Dr. Şebnem KAYA and Asst. Prof. Dr. Evrim DOĞAN ADANUR for their scholarly support and invaluable suggestions. I would also like to thank Dr. Suganthi John and Michelle Devereux who supported me by their constant motivation at CARE at the University of Birmingham. They were the two angels whom I feel myself very lucky to meet and work with. I also would like to thank Prof. Dr. Michael Dobson, the director of the Shakespeare Institute and all the members of the Institute who opened up new academic horizons to me. I would like to thank Dr. -

The Battle of Good and Evil in Shakespeare

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses Summer 2015 The aB ttle of Good and Evil in Shakespeare Erin K. Miller [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Erin K., "The aB ttle of Good nda Evil in Shakespeare" (2015). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 70. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/70 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Battle of Good and Evil in Shakespeare A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies by Erin Miller July 2015 Mentor: Dr. Patricia Lancaster Reader: Dr. Jennifer Cavenaugh Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Master of Liberal Studies Program Winter Park, Florida 2 Introduction Drama through the ages—from the Greeks’ Oedipus Rex to the morality plays of the Middle Ages —centers on an exploration of the human condition. In antiquity, religious celebrations to honor the gods and appeal for their favor gradually give birth to Greek theater, and these early plays, most of which are tragedies, focus on man’s suffering. What starts as the impact of fate on the life of man becomes, by the Middle Ages, a religious spectacle centered on evil’s impact on man. The Church of the Middle Ages frames the battle as a conflict of vice and virtue through stories in the life of Christ. -

Single Tickets Go on Sale September 13 Theatre for a New Audience's a Midsummer Night's Dream Polonsky Shakespeare Center Julie

The Bruce Cohen Group, Ltd For Immediate Release, Please Contact: Bruce Cohen 212 580 9548 [email protected] Single Tickets Go On Sale September 13 For Theatre for a New Audience's A Midsummer Night's Dream At its newly named building Polonsky Shakespeare Center Julie Taymor Directs Elliot Goldenthal Composes Original Music Previews Begin October 19; Opens November 2 BROOKLYN -- Single tickets go on sale September 13 for Theatre for a New Audience’s inaugural production of A Midsummer Night's Dream, directed by multiple Tony Award-winner Julie Taymor with original music composed by Academy Award and Golden Globe-winning Elliot Goldenthal, at the Theatre’s newly-named building, Polonsky Shakespeare Center, 262 Ashland Place between Lafayette Avenue and Fulton Street, Brooklyn. A Midsummer Night's Dream by William Shakespeare features a cast of 36 led by Tina Benko as Titania, Max Casella as Bottom, David Harewood as Oberon and Kathryn Hunter as Puck. Previews begin previews October 19, for an opening November 2. Founding Artistic Director Jeffrey Horowitz explained, “Julie and Elliot are innovative, adventurous artists. We first worked together in 1984 on a 60-minute version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream for Theatre for a New Audience presented at the Public Theater. Twenty-nine years later, it’s thrilling they are directing and composing our first full production of A Midsummer Night's Dream, the inaugural presentation in our first permanent home.” Theatre for a New Audience just named its building Polonsky Shakespeare Center in recognition of a $10 million gift from the Polonsky Foundation. -

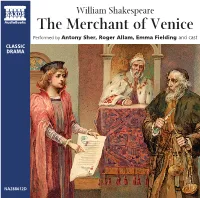

The Merchant of Venice Performed by Antony Sher, Roger Allam, Emma Fielding and Cast CLASSIC DRAMA

William Shakespeare The Merchant of Venice Performed by Antony Sher, Roger Allam, Emma Fielding and cast CLASSIC DRAMA NA288612D 1 Act 1 Scene 1: In sooth, I know not why I am so sad: 9:55 2 Act 1 Scene 2: By my troth, Nerissa, my little body is aweary… 7:20 3 Act 1 Scene 3: Three thousand ducats; well. 6:08 4 Signior Antonio, many a time and oft… 4:06 5 Act 2 Scene 1: Mislike me not for my complexion… 2:26 6 Act 2 Scene 2: Certainly my conscience… 4:21 7 Nay, indeed, if you had your eyes, you might fail of… 4:19 8 Father, in. I cannot get a service, no; 2:49 9 Act 2 Scene 3: Launcelot I am sorry thou wilt leave my father so: 1:15 10 Act 2 Scene 4: Nay, we will slink away in supper-time, 1:50 11 Act 2 Scene 5: Well Launcelot, thou shalt see, 3:16 12 Act 2 Scene 6: This is the pent-house under which Lorenzo… 1:32 13 Here, catch this casket; it is worth the pains. 1:49 14 Act 2 Scene 7: Go draw aside the curtains and discover… 5:04 15 O hell! what have we here? 1:23 16 Act 2 Scene 8: Why, man, I saw Bassanio under sail: 2:27 17 Act 2 Scene 9: Quick, quick, I pray thee; draw the curtain straight: 6:48 2 18 Act 3 Scene 1: Now, what news on the Rialto Salerino? 2:13 19 To bait fish withal: 5:17 20 Act 3 Scene 2: I pray you, tarry: pause a day or two… 4:39 21 Tell me where is fancy bred… 6:52 22 You see me, Lord Bassanio, where I stand… 9:56 23 Act 3 Scene 3: Gaoler, look to him: tell not of Mercy… 2:05 24 Act 3 Scene 4: Portia, although I speak it in your presence… 3:56 25 Act 3 Scene 5: Yes, truly; for, look you the sins of the father… 4:28 26 Act 4 Scene 1: What, is Antonio here? 4:42 27 What judgment shall I dread, doing. -

SHAKESPEARE in PERFORMANCE Some Screen Productions

SHAKESPEARE IN PERFORMANCE some screen productions PLAY date production DIRECTOR CAST company As You 2006 BBC Films / Kenneth Branagh Rosalind: Bryce Dallas Howard Like It HBO Films Celia: Romola Gerai Orlando: David Oyelewo Jaques: Kevin Kline Hamlet 1948 Two Cities Laurence Olivier Hamlet: Laurence Olivier 1980 BBC TVI Rodney Bennett Hamlet: Derek Jacobi Time-Life 1991 Warner Franco ~effirelli Hamlet: Mel Gibson 1997 Renaissance Kenneth Branagh Hamlet: Kenneth Branagh 2000 Miramax Michael Almereyda Hamlet: Ethan Hawke 1965 Alpine Films, Orson Welles Falstaff: Orson Welles Intemacional Henry IV: John Gielgud Chimes at Films Hal: Keith Baxter Midni~ht Doll Tearsheet: Jeanne Moreau Henry V 1944 Two Cities Laurence Olivier Henry: Laurence Olivier Chorus: Leslie Banks 1989 Renaissance Kenneth Branagh Henry: Kenneth Branagh Films Chorus: Derek Jacobi Julius 1953 MGM Joseph L Caesar: Louis Calhern Caesar Manluewicz Brutus: James Mason Antony: Marlon Brando ~assiis:John Gielgud 1978 BBC TV I Herbert Wise Caesar: Charles Gray Time-Life Brutus: kchard ~asco Antony: Keith Michell Cassius: David Collings King Lear 1971 Filmways I Peter Brook Lear: Paul Scofield AtheneILatenla Love's 2000 Miramax Kenneth Branagh Berowne: Kenneth Branagh Labour's and others Lost Macbeth 1948 Republic Orson Welles Macbeth: Orson Welles Lady Macbeth: Jeanette Nolan 1971 Playboy / Roman Polanslu Macbe th: Jon Finch Columbia Lady Macbeth: Francesca Annis 1998 Granada TV 1 Michael Bogdanov Macbeth: Sean Pertwee Channel 4 TV Lady Macbeth: Greta Scacchi 2000 RSC/ Gregory -

Edition 4 | 2018-2019

BROADWAY AT THE TENNESSEE 9 WORK LIGHT PRODUCTIONS STEPHEN GABRIEL, PRODUCER PRESENT BOOK BY KAREY KIRKPATRICK AND JOHN O’FARRELL MUSIC AND LYRICS BY WAYNE KIRKPATRICK AND KAREY KIRKPATRICK CONCEIVED BY KAREY KIRKPATRICK AND WAYNE KIRKPATRICK STARRING MATTHEW BAKER MATTHEW MICHAEL JANISSE GREG KALAFATAS EMILY KRISTEN MORRIS MARK SAUNDERS JENNIFER ELIZABETH SMITH RICHARD SPITALETTA DREW ARISCO ABBY BARTISH EMMA BENSON ZACHARY BIGELOW KATIE SCARLETT BRUNSON JULIAN BURZYNSKI JR. BRIAN COWING ALEX EISENBERG TIM FUCHS ROBERT HEAD DEVIN HOLLOWAY DANNY LOPEZ KEELEY ANNE McCORMICK NICK PANKUCH AVEENA SAWYER ALLISON C. SCOTT PETER SURACE DORSEY ZILLER SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN SCOTT PASK GREGG BARNES JEFF CROITER PETER HYLENSKI CASTING HAIR DESIGN MAKEUP DESIGN PRODUCTION MANAGER WOJCIK | SEAY CASTING JOSH MARQUETTE MILAGROS PORT CITY TECHNICAL MEDINA-CERDEIRA PRODUCTION STAGE MANAGER ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR MUSIC DIRECTOR & CONDUCTOR KRISTIN SUTTER STEVE BEBOUT MATTHEW CROFT TOUR MARKETING TOUR BOOKING AGENCY GENERAL MANAGEMENT ALLIED TOURING THE BOOKING GROUP WORK LIGHT PRODUCTIONS RICH RUNDLE, BRIAN BROOKS MUSIC SUPERVISOR & VOCAL ARRANGEMENTS ORCHESTRATIONS MUSIC ARRANGEMENTS ASSOCIATE MUSIC SUPERVISOR PHIL RENO LARRY HOCHMAN GLEN KELLY BRIAN P. KENNEDY DIRECTED AND CHOREOGRAPHED BY CASEY NICHOLAW ORIGINALLY PRODUCED ON BROADWAY BY KEVIN McCOLLUM, BROADWAY GLOBAL VENTURES, CMC, MASTRO/GOODMAN, JERRY & RONALD FRANKEL, MORRIS BERCHARD, KYODO TOKYO INC., WENDY FEDERMAN, BARBARA FREITAG, LAMS PRODUCTIONS, WINKLER/DESIMONE, -

Shylock : a Performance History with Particular Reference to London And

University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. CHAPTER 1 SHYLOCK & PERFORMANCE Such are the controversies which potentially arise from any new production of The Merchant of Venice, that no director or actor can prepare for a fresh interpretation of the character of Shylock without an overshadowing awareness of the implications of getting it wrong. This study is an attempt to describe some of the many and various ways in which productions of The Merchant of Venice have either confronted or side-stepped the daunting theatrical challenge of presenting the most famous Jew in world literature in a play which, most especially in recent times, inescapably lives in the shadow of history. I intend in this performance history to allude to as wide a variety of Shylocks as seems relevant and this will mean paying attention to every production of the play in the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre and the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, as well as every major production in London since the time of Irving. For reasons of practicality, I have confined my study to the United Kingdom1 and make few allusions to productions which did not originate in either Stratford or London. -

The Merchant of Venice

Shakespeare The Merchant of Venice SYNOPSIS The Merchant of Venice Antonio, the merchant of Venice, lends three thousand ducats to his friend Bassanio to help him woo the wealthy and beautiful Portia of Belmont, an estate some way away from Venice. Because Antonio's money is invested in ships bringing cargoes back to Venice, Antonio borrows the money from Shylock, a Jewish moneylender. The Jews have been badly treated by the Italians, and Antonio has criticized Shylock in the past for his high rates of interest. Shylock agrees to lend, however, under the strange condition that if Antonio fails to repay the loan, Shylock can take a pound of his flesh instead. Bassanio's friend Lorenzo runs away with Shylock's daughter Jessica, and Jessica also steals some of her father's money. Portia's father has arranged in his will that Portia will marry whoever chooses the right one of three caskets made of gold, silver and lead. Wealthy suitors from Morocco and Aragon fail, but Bassanio chooses the right, lead, casket. His friend Gratiano marries Portia's companion Nerissa at the same time. News arrives that Antonio's ships have all been lost. The court, under the Duke, must decide whether Shylock can take his pound of flesh. After all that has happened, Shylock insists on it. Without telling their husbands, Portia and Bassanio appear before the court as (male) lawyers, and after establishing that the agreement is correct, they point out that it does not mention blood, so no blood must be spilt. When Shylock now claims money instead, Portia points out that the punishment for attempting to kill a Venetian is death. -

Horowitz- Shylock After Auschwitz: the Merchant of Venice

ARTHUR HOROWITZ Pomona College SHYLOCK AFTER AUSCHWITZ : THE MERCHANT OF VENICE ON THE POST -HOLOCAUST STAGE —SUBVERSION , 1 CONFRONTATION , AND PROVOCATION hakespeare wrote several plays that have been assigned the designation ‘problem plays’. These plays have been defined, as rudimentarily as S 2 possible, as those “in which point of view is ambiguous” Often lumped into this uncertain family/genre are Hamlet, All’s Well That Ends Well, Troilus and Cressida, Antony and Cleopatra, and Measure for Measure— problematic plays of sober realism, to be sure. But over this past century, a different varietal of Shakespearean drama has emerged as far more problematic. These plays’ problems are caused by their social emphases far more than by whatever vagueness of viewpoint or characterization might be contained within. Their controversies revolve around matters of sexism, racism, oppressionist/colonialism, anti-Semitism—issues Shakespeare, more than likely barely considered. No matter. The Taming of the Shrew, The Tempest, Othello and The Merchant of Venice have become plays requiring nearly super-human delicacy if they are to be staged today. These newly considered problem plays interpretation of Shakespeare’s raw material is quite at odds with that which most probably inspired Shakespeare’s original concept. Today, one does not mount a production of The Taming of the Shrew without most carefully considering issues of gender, and how a post- feminist world perceives the very notion of a willful, sharp-witted young woman’s necessity for a ‘good taming’. Contemporary productions of The Tempest must confront the increasingly negative perception of Prospero, no longer benign father figure, preparing, as he approaches his dotage, to mete out 1 I would like to gratefully acknowledge the extensive contributions to this paper of Christina Hurtado (Pomona College, ’06). -

Problem Plays’ Because It Provides Terms for Viewing Plays Outside of the Implied Zero-Sum Game of the Comedy/Tragedy Dichotomy

Alistair Welch for: Deana Rankin 12.11.07 “All that is tragic rests on an irreconcilable antithesis. As soon as reconciliation is initiated, or becomes possible, the tragic disappears.” (GOETHE) Lucien Goldmann in his essay on Racine defines tragedy in relation to serious drama, he calls tragedy, “any play in which the conflicts are necessarily insoluble”1 whilst drama is “any play in which the conflicts either are solved or fail to be solved because of the fortuitous intervention of a factor which, according to the laws governing the universe of the play might not have operated”2. Goldmann’s separation of tragedy from serious drama is instructive in an analysis of Shakespeare’s so-called ‘problem plays’ because it provides terms for viewing plays outside of the implied zero-sum game of the comedy/tragedy dichotomy. Goethe’s citation implies that any concession in the tragic is tied to a rise in the comic, but this model does not allow for the awkward co-existence of tragic and comic elements. This essay is interested in how Measure for Measure, All’s Well that Ends Well and The Merchant of Venice, all entered as comedies in the 1623 Folio, are serious dramas, but despite containing certain tragic features might never be called tragedies. Hegel envisages the “clearest power”3 in tragedy as the conflict between state and family loyalties, which in a play like Sophocles’ Antigone is seen to be utterly irreconcilable. The Merchant of Venice stages a number of clashes between codes of behaviour that seem to have tragic potential.